1.

The Issue ^

The electronic media is not inherently observable like paper documents. Hence, auditability and reproducibility are serious issues as shown in the following illustrative examples:

In regional elections in Finland 2008, more than 200 electronic votes «disappeared» – the Supreme Administrative Court ordered the election to be repeated on paper (Karhumäki et al., Editorial ORF). The «disappearance» of votes could indicate that there was no audit trail in place covering the entire election process, for otherwise said votes could have been traced by following the process audits step by step.

In the U.K. regional elections in 2007, staff of the software vendor had to manually edit clear-text votes because they would not fit into the counting application. The election committee was unable to follow the procedures for opening the electronic ballot box and counting the votes, which was managed by vendor staff and involved the usage of command line interface procedures on notebooks provided by the software vendor (Actica §6.2.10). In the same election, election observers of the Open Rights Group observed undocumented data transfers between election servers by USB stick during the ongoing election. (Open Rights Group, p.18). Both incidences could indicate a far reaching loss of control by the election authorities and that vendor staff acted outside proper constitutional control. Furthermore, it is doubtful whether the manual editing of ballots by vendor staff is consistent with the auditability requirements of an election process.

Press reports indicate that in the aftermath of the eVoting pilot conducted in the Austrian Student Union Elections 2009, the head of the election committee accompanied by an armed guard boarded a fire fighting vehicle and took the computer disks that could have enabled to trace each vote back to the voter to a service provider specializing in computer disk erasure (Moser). It was unclear, whether this included all backups and if so, how the number of backups was ascertained in the first place. Destruction of voting data effectively rules out any ex post control by the courts, as the data basis for any judicial control has been destroyed. Such procedures provide a protection of voting secrecy at the expense of auditability – and the report shows that the protection is purely organisational, anyway. Several complaints have in fact been filed and due to severe technical shortcomings, the eVoting part of the election at Vienna’s main university was annulled and is to be repeated on paper (Prosser); further complaints are still processed by the Federal Election Commission.

Also the ruling of the German Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) banning the use of the type of voting machines that was used in the 2005 Federal Elections mainly argued its case in terms of auditability and reproducibility.

2.

Definitions ^

For further discussion, let us give a definition of auditability:

- Verification that all recorded votes (and only them) are counted as recorded in the electronic ballot box.

- Verification that all cast votes (and only them) were recorded in the ballot box as cast by the voter.

- Verification that votes were only cast by eligible voters within their voting rights.

«Verification» in this contects means the inter-personal and permanent possibility to ascertain whether the above statements are true for an election or part thereof. The emphasis is on inter-personal; a proof which alerts the voter to the fact that her vote was not counted correctly is useless if no outside person – in particular the election committee or a court – is able to verify whether the assertion of the voter is true or not. The following example shows a (hypothetical) verification scheme that does not fulfil this inter-personal requirement:

This verification scheme would enable the voter to check for himself, whether his vote was recorded correctly, however, in the case of a discrepancy he would never be able to prove it to another person, unless that person observed or filmed V when voting. Even if a number of people asserted malpractice, the above verification scheme does not enable to distinguish between a concerted sabotage campaign or a series of valid complaints. It is hence not inter-personal.

3.

Trust Model ^

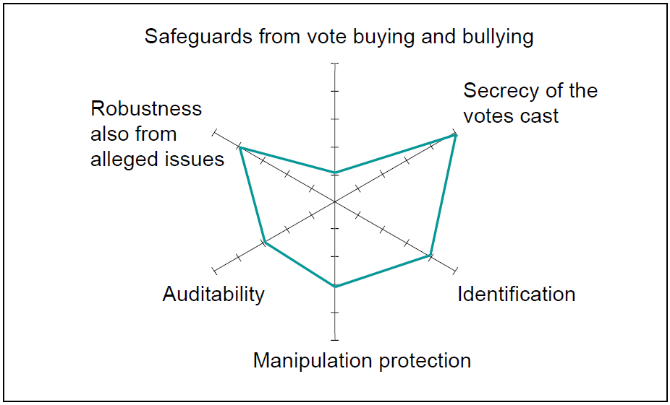

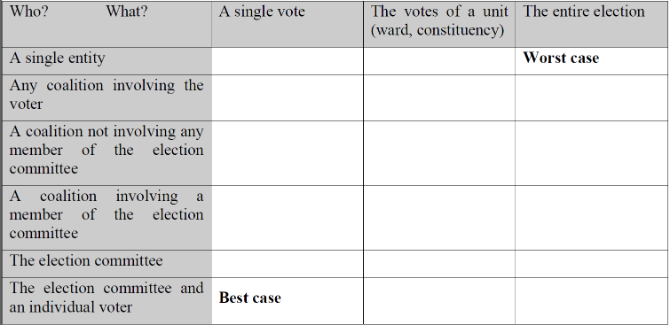

EVoting systems have to adhere to the General Voting Principles (Mayer, p. 194 et seq.). On a more technical level, these can be broken down to a number of technical requirements, which are depicted in Figure 1. Each of the dimensions lists a security aim of an eVoting system (cf. Volkamer et al, Uhrmann, Ondrisek):

- Voting secrecy before the vote is cast to prevent coercion and vote-buying.

- Voting secrecy after the vote has been submitted to the system to prevent a match between voter and ballot; if a system enables the voter to check whether her vote was counted, the procedure must not enable the voter to prove to anybody how she voted as this would enable vote buying or voter coercion.

- Identification, where impersonation and submission of multiple votes via the same or different voting channels is prevented to ensure the equality of each vote.

- Manipulation of the vote, either by the voter himself, third parties or – by far the most dangerous attacker – the administration of the election system.

- Auditability and reproducibility of the results.

- Robustness including protection from sabotage, which not only includes all kind of debilitating attacks on the system, but also the assertion of manipulations and fraud that is difficult to counter.

The question however is, whether these principles are protected by organisational or technical means and how far the technical safeguards go. The connecting line in Figure 1 indicates how far the respective aim is achieved by technical means. Beyond this line, only organizational safeguards are possible, such as distributing responsibility among several authorities preventing them to unite their data or obliging authorities to completely destroy certain data at some stage at the process.

4.1.

Verification that votes were only cast by eligible voters ^

Here, auditability has to start with the voter roll loaded into the eVoting system, where standard measures of protecting data integrity (hash values, data encryption) should be implemented, these are measures that protect the data from fraud by the system and database administration of the election system. Also unauthorised usage of voting rights has to be prevented. Protocols that incorporate an independent election observation authority as an integral element of the entire eVoting protocol, such as the «Verifier» in protocol (Prosser et al.), provide safeguards against the election or system administration forging election rights and votes cast upon them, resp. The eligibility of each vote cast should eventually be traceable to a voting right rooted in the election database and that was confirmed by the Verifier (= independent electronic election observer).

4.2.

Verification that all cast votes were recorded in the ballot box as cast by the voter ^

Each vote must be inextricably linked to such a voting right, the very moment it is cast by the voter in the voting client. The exact linking mechanism depends on the artefact. Possibilities include hashing, other methods of concatenation, enveloping or digital signatures. In any case, the insertion of a vote that was not originally cast on a valid voting right must be detected.

However, the question remains, whether any valid votes were completely suppressed.

If receipt of a vote is recorded in a tamper-resistant logging system, the number of votes received according to the log and the actual number of valid votes may be compared. Beyond that, protocols involving an independent observer provide additional safeguards. If the observer recorded, say, 10000 voting procedures and only 7100 votes were recorded, a serious enquiry would be indicated. Also publication of the voting right artefact of all votes that were counted would enable voters to ascertain whether their vote was counted. This, of course, is by no means also the assurance that they were counted correctly, this has to be verified by the mechanisms outlined in the following Section.

4.3.

Verification that all recorded votes are counted as recorded in the electronic ballot box ^

For each vote to be counted, there must be the following data: The confirmed voting right and the link between the vote itself and the voting right. «Counting» therefore applies to the following process steps: (i) Decryption of the votes, (ii) verification of the link between vote and artefact, (iii) verification of the authenticity of the artefact. This would also correspond to the paper-based counting process, where not just the selected choices on the ballot sheets are counted, but where it is also ascertained whether they stem from the sealed ballot box, which was supervised by the election committee during the voting process.

However, what if one does not trust this counting mechanism? In this case alternative systems may be offered to reproduce the count. But again, such a recount must also incorporate the checks mentioned above. There is however, one pre-requisite to do this transfer: it must not compromise voting secrecy. This in turn requires that the anonymization of the vote happens before the vote is cast and not afterwards. Only in this case, the electronic ballot box does not contain any voter-related information and hence can be transferred to other organisations without also passing on the information voter – vote. Only certain classes of voting protocols fulfil this property. Examples are eVoting protocols based on homomorphic functions (cf. Schoenmakers and Cohen et al. or the protocol proposed in Prosser et al.).

If, on the other hand, the anonymization of the vote happens after the vote was cast, such as in digital envelope-based protocols, an independent recount either represents a massive threat to voting secrecy (see the discussion in Maaten), if the original ballot box is transferred to the recounting authority. Also mechanisms proposed for manipulation protection to such algorithms do generally not remedy this fundamental issue (cf. Gennaro or Sako et al.).

5.

Conclusion ^

Considerable issues have been raised in several eVoting pilots due to lack of auditability. That is also why the Council of Europe has attached high importance to this point in its 2004 Recommendation on eVoting.

This paper developed a framework for determining the degree of independent auditability and a set of operational criteria to assess that degree also in goal antinomy to other aims in an eVoting system. The next step in the research work will be to transform the verbal description of said criteria into a formal framework that can also be used in formal software verification methods.

6.

References ^

Karhumäki, J., Meskanen, T., Audit report on pilot electronic voting in municipal elections, University of Turku, Turku (2008).

Editorial ORF, E-Voting-Wahlgang in Finnland ungültig, futurezone, ORF, http://futurezone.orf.at/stories/1602230 retrieved 20.1.2010 (2009).

Actica, Technical Evaluation of Rushmoor Borough Council e-voting Pilot 2007, Electoral Commission of the United Kingdom, London http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/elections/pilots/May2007 retrieved 20.1.2010 (2007).

Open Rigths Group, May 2007 Election Report, Open Rights Group, London, http://www.openrightsgroup.org/category/issues/evoting-issues retrieved 20.1.2010 (2007).

Moser, K: Beschwerdeflut bei ÖH-Wahl, derstandard.at, 24.6.2009, http://derstandard.at/fs/1245819977111/E-Voting-Beschwerdeflut-bei-OeH-Wahl retrieved 20.1.2010 (2009).

Prosser, A.: Es geht in erster Linie um die Transparenz; Gastkommentar in der «Wiener Zeitung» vom 10.12.2009.

Bundesverfassungsgericht, Spruch BVerfG, 2 BvC 3/07 and 2 BvC 4/07 from 3.3.2009, Karlsruhe, http://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/entscheidungen/cs20090303_2bvc

000307.html retrieved 20.1.2010.

Mayer, H., Bundes-Verfassungsrecht – Kurzkommentar, 4th Ed.; Manz Verlag, Wien, (2007).

Volkamer, M., Hutter, D., From Legal Principles to an Internet Voting System, in: Prosser, A., Krimmer, R. (eds.), Electronic Voting in Europe – Technology, Law, Politics and Society, GI Verlag, Bregenz, pp. 111-120 (2004).

Uhrmann, P., Das Potential von e-Voting, in: Prosser, A., Krimmer, R. (eds.), e-Democracy, Technologie, Recht und Politik, OCG Verlag, Vienna, pp. 163-174 (2003).

Ondrisek, B., Sicherheit elektronischer Wahlen; VDM Verlag, Saarbrücken (2008).

Prosser, A., Müller-Török, R., «E-Democracy, Eine neue Qualität im demokratischen Entscheidungsprozess». Wirtschaftinformatik, 6/2002, pp. 545-556 (2002).

Schoenmakers, B.: A Simple Publicly Verifyable Secret Sharing Scheme and its Application to Electronic Voting, Lecture Notes in Computer Science Vol. 1666, pp. 148-164 (1999).

Cohen, J., Fischer, M.: A Robust and Verifyable Cryptographically Secure Election Scheme, IEEE Symposium on the Foundations of Computer Science, pp. 373-382 (1996).

Maaten, E., Towards Remote E-Voting: Estonian Case”, in: Prosser A., Krimmer R. (eds.), Electronic Voting in Europe – Technology, Law, Politics and Society), GI Verlag, Bregenz, pp. 83-100 (2004).

Sako, K., Kilian, J., Receipt-Free Mix-Type Voting Scheme: A Practical Solution to the Implementation of a Voting Booth,” EUROCRYPT ’95, vol 921, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer-Verlag, pp. 393-403 (1995).

Gennaro, R., A Receipt-Free Election Scheme Tolerating a Dynamic Coercer (with Applications to Key Escrow), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1995)

Council of Europe, Recommendation 2004(11) of the Committee of Ministers to member states on legal, operational and technical standards for e-voting, Strasbourg (2004).

Professor, Wirtschaftsuniversität Wien, Institut für Produktionsmanagement

Augasse 2-6, 1090 Wien, AT, prosser@wu.ac.at, http://e-voting.at

- 1 We assume that this information does not enable the election authority to ascertain how the voter voted, eg., by encrypting the vote itself, stripping the vote of the identifying envelope (including the option number) and passing it on to another authority to open and count.