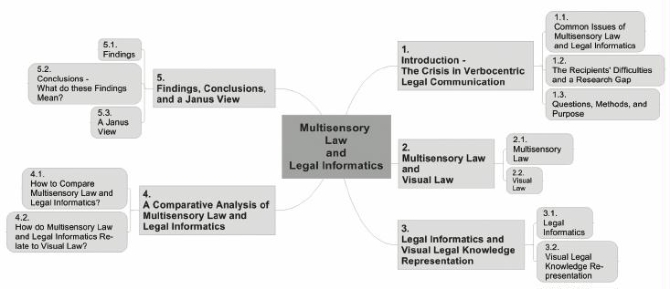

1.1.

Common Issues of Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics ^

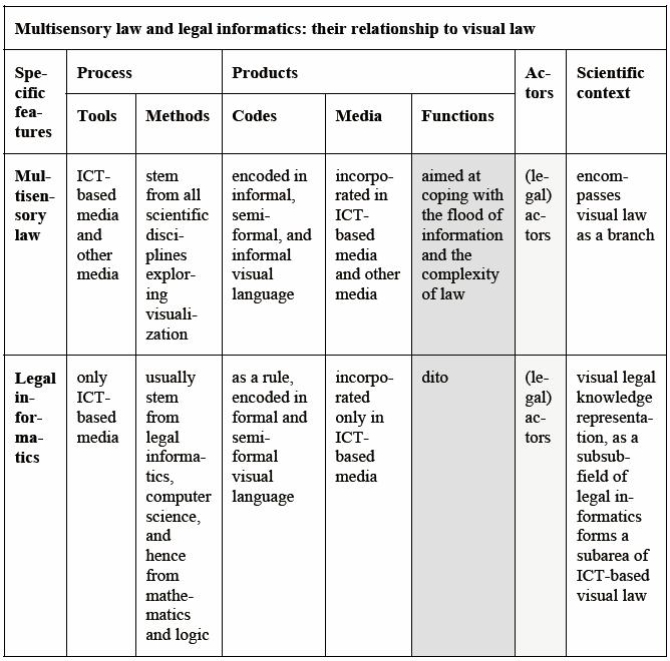

Multisensory law and legal informatics are concerned with the flood of verbal legal information and the complexity of law. Both disciplines seek to develop solutions designed to help lawyers or laypersons cope with these pressing phenomena.1 This paper focuses on how these legal disciplines relate to visual law, and on its potential to provide appropriate solutions. The question whether multisensory law and legal informatics are legal disciplines will be discussed later.2

It has become almost banal to observe the flood of verbal legal information and the complexity of verbal law. But what is far from clear is what exactly «the flood of legal information» and «the complexity of verbal law» mean.

1.1.1.

The Flood of Verbal Legal Information ^

Information society can be characterized by the explosion of information, or – to use another metaphor common in this context – by the swamping or inundating of its users with information.3 Nor has this development spared the legal context. Already in 1970, SIMITIS referred to the information crisis of the law. What did he mean by this? He posited that knowledge of jurisdiction becomes a matter of coincidence. Further, he suggested that the legal actors» knowledge of legal norms amounts to a torso.4 In 1981, LACHMAYER labelled this phenomenon as a communication crisis of the law.5 Even today, an actual flood of legal information prevails – even though the retrieval of legal information (for instance, legal databases and legal information management in its different implementations) is quite efficient.6 There is a debate on the semantics of the term «legal information.»7 It would go beyond the scope of this paper to contribute fully to this discussion. For the purposes of this paper, «legal information» is subsumed under «law.» Here, «legal knowledge,» a term that is pre-eminently used in legal informatics,8 refers to knowledge with respect to the law.9 What is meant here by «law» will be clarified in the context of «multisensory law.»

1.1.2.

The Complexity of Verbal Law ^

Dazu kommt ein zweiter Einflussfaktor, der das Recht in seiner Leistungsfähigkeit zunehmend strapaziert: die wachsende Komplexität der Umweltbedingungen und die Dynamisierung der Soziallagen. Das rechtlich zu Ordnende hat einen immer unübersichtlicheren, unbeständigeren Charakter. Die Entwicklungen in Forschung und Technik sind rasant und weitgehend nur noch für den Spezialisten nachzuvollziehen. Aber auch die Realitäten des menschlichen Zusammenlebens sind von schnellem Wandel, zunehmendem Pluralismus und steigender Unübersichtlichkeit geprägt. […] Notwendigerweise kopieren sich in dieser Konstellation die Dynamisierung und Verkomplizierung der Umweltbedingungen in das Recht hinein.]»13

Therefore, the law reflects the complexity of the various extra-legal contexts, such as the cultural, political, social, technical, and economic contexts. This complexity becomes apparent in legal terminology and syntax.14 Furthermore, it manifests itself in the

[zahlreiche[n] Überlappungen verschiedener Rechtsmassen, die zueinander in einem nicht von vornherein geklärten Verhältnis stehen: einfachgesetzliches Recht – Verfassungsrecht (Privatrecht und Grundrechte); Gesetzesrecht – Richterrecht; nationales Recht – Europa- und Einheitsrecht; staatliches Recht – Selbstregulierung der Wirtschaft.»]15

In his recent «Das Normalfall Buch», HAFT characterizes «complexity» as follows:

[Komplexität ist durch acht Merkmale gekennzeichnet, die man in jedem Rechtsfall nachweisen kann. Es gibt eine Mehrzahl von Aspekten. Die Aspekte bilden Aspekt-Hierarchien. Die Aspekte sind «Mehr-oder-Minder»-Aspekte. Die Aspekte bilden Systeme. Die Systeme sind eigendynamisch. Es gibt eine Vielzahl von möglichen Zielen (Polytelie). Zwischen den Zielen gibt es Konflikte und Widersprüche. Es gibt Informationsdefizite.]»16

Although HAFT’s notion of complexity refers to legal cases and not to the law, it can nevertheless be transferred to the latter. In other words, the law exhibits countless aspects, «sub-aspects thereof, sub-sub-aspects thereof, and so forth [Zu den Aspekten gehören Unter-Aspekte, und zu diesen jeweils wieder Unter-Unteraspekte, und so fort]»17 (features 1 and 2). These aspects of the law «are networked; they build systems [sind vernetzt; sie bilden Systeme]»18 (feature 4). This implies that «no legal aspect can ever be treated in isolation. It is always embedded in systems of other aspects. On their part, these are once more enmeshed elsewhere – and so forth. [Kein juristischer Aspekt kann jemals isoliert betrachtet werden. Stets ist er eingebettet in Systeme aus anderen Aspekten.]»19 These systems develop considerable momentum (feature 5):

[Beim ‹systemischen› Denken, [sic] neigt man dazu, sich auf den Ist-Zustand zu konzentrieren statt an die Zukunft zu denken. Die Frage ‹Was wird?› wird oftmals über der Frage ‹Was ist?› vernachlässigt. Wir sind gewohnt, unseren Fokus auf Zustände statt auf Prozesse zu lenken.]»20

1.1.3.

Structuring the Law ^

The verb «to structure» comes from the Latin «struere .» Among many other meanings, it denotes «to arrange» («ordnen» or «anordnen» in German).21 Further, «to structure» embodies a process.22 Derived from HAFT’S concept of the term «structure,»23 «to structure» could be paraphrased as a process in which elements are arranged in a certain way and interconnected.

It is necessary to distinguish between the quantitative and qualitative features of structuring methods. With respect to quantitative features, there is a controversy about how many elements (structure points), respectively chunks, the entities of (legal) information have to be organized into so that their recipients are able to assimilate, process, memorize, and recall them. In the relevant literature, the number of these chunks varies between nine (that is, seven, plus or minus two) and three.24 In relation to the qualitative aspects, different methods are applied to structure complexity. Reviewing the various structuring methods would go far beyond this outline. Importantly, however, we need to differentiate between purely verbal, visual, and verbovisual structuring methods.

Currently, so-called concept trees («Begriffsbäume» in German) are used to verbally structure the content of legal texts.25 The different mapping methods stem from a range of visual and verbovisual structuring methods. By using different mapping methods, such as concept mapping,26 information mapping,27 knowledge mapping,28 and mind mapping,29 the law can or could be (verbo-)visually structured.30 To cite two concrete examples, contracts are also structured with the help of concept mapping,31 and mind maps are used to verbovisually structure legal information on e-government websites.32

1.2.

The Recipients' Difficulties and a Research Gap ^

«Due to the weakening of the extra-legal social orders, the meagre knowledge of legal norms threatens the effectiveness of the law; nowadays, more than in former times, the knowledge of the law represents a basic condition for legal norms to have an effective influence on society. Considering the growth of the legal matter in the welfare state, there are limits to remedying the lack of legal knowledge.[Der geringe Kenntnisstand von Rechtsvorschriften ist infolge der Schwächung der ausserrechtlichen Sozialordnungen für die Effektivität des Rechts bedrohlich; denn die Kenntnis des Rechts bildet heute mehr als früher eine grundlegende Bedingung für einen wirksamen Einfluss der Rechtsnormen in der Gesellschaft. Dem Mangel an Rechtskenntnis kann jedoch angesichts des Anwachsens des Rechtsstoffes im Sozialstaat nur beschränkt abgeholfen werden.]»35

«In the case of derogations, it thus occurs that the legislator, being unsure whether the previous law is still in force, and to which extent, for the sake of caution, inserts the clause ‹… shall be abrogated provided that it is still in force›[So kommt es vor, dass bei Derogationen der Gesetzgeber sich nicht sicher ist, ob das bisherige Recht, und in welchem Ausmass, noch gilt, so dass der Vorsicht halber die Klausel ‹…wird aufgehoben, sofern es noch gilt› eingefügt wird.]»38

Recipients also have difficulties in managing the complexity of the law. These difficulties mainly concern comprehension.39 Nevertheless, emotional and cognitive difficulties can go hand in hand. HAFT refers to «the excessive demand of complexity on the human being [die Überforderung des Menschen durch Komplexität.»]40

Scant knowledge exists to date about how multisensory law and legal informatics develop visual solutions for coping with the flood of verbal legal information and the complexity of verbal law. Below, I approach this research gap by comparing these visual solutions.

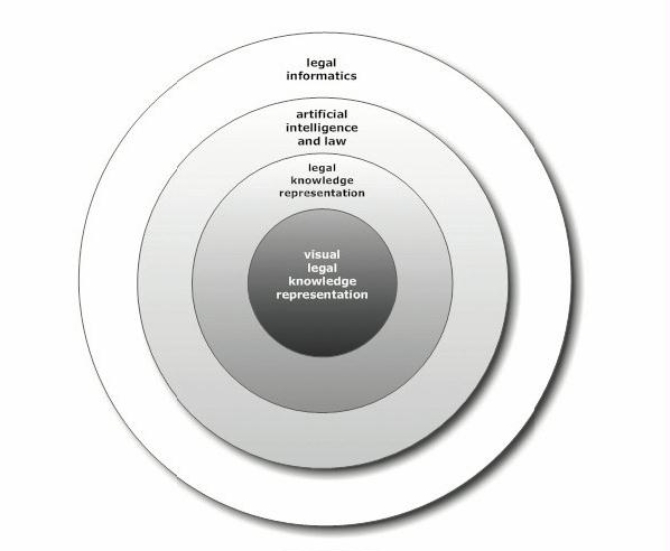

To my knowledge, no such comparative analysis has been conducted so far. ČYRAS, for instance, compares knowledge visualization with knowledge representation in legal informatics.41 In its attempt to advance discussion in this area, this paper focuses on two different legal disciplines (multisensory law and legal informatics) and their relationship to visual law.

1.3.

Questions, Methods, and Purpose ^

The above problems prompt various questions: how do multisensory law and legal informatics relate to visual law? In relating to visual law, what do they have in common, how are they similar, and how are they different? As multisensory law is still a relatively unknown legal discipline, I first clarify the term «multisensory law,» its subject matter, and its cognitive interest. I then compare the disciplines involved before proceeding likewise with «visual law.» Notwithstanding its brief history, legal informatics is already well-known, at least in the relevant legal circles. I therefore dispense with an in-depth discussion here. In what follows, I draw on the philosophical method of comparison. Furthermore, I will adopt insights from various disciplines, such as legal informatics, legal theory, and multisensory law. The paper aims to sketch answers to the above questions and various related questions.

2.1.1.

The Term «Multisensory Law» ^

Understanding the term «multisensory law» requires clarifying the adjective «multisensory,» the noun «law,» and how these words are related.

2.1.1.1.

«Multisensory» ^

In default of any specific legal discourse, I draw on three extra-juridical discourses to explain the adjective «multisensory»: the psychology of learning, the neurosciences, and the psychology of perception. These discourses differentiate between stimuli and their perception. «Multisensory» implies that, at all times, more than one stimulus is involved in affecting a human being.42 In a sensory respect, these stimuli are different.43 Moreover, they coincide in space44 and time.45 Multisensory stimuli also occur in the legal context: for example, consider a law lecture at the university, a lawyer’s plea, the seller’s offer to a buyer during a sales meeting, and so forth. In these cases, these stimuli are at least audiovisual. The recipient can hear and see them, and they coincide in space and time. As regards the effect of stimuli on human perception, two or more perceptive systems are constantly and simultaneously active.46 They are simultaneously active – or phrased more precisely:

[Dabei werden Umweltinformationen von den Rezeptoren der verschiedenen Sinnesmodalitäten in elektrische Nervenimpulse umgewandelt, im Gehirn zusammengetragen, integriert und zu einer einheitlich schlüssigen Wahrnehmung, dem Perzept, verarbeitet.]»47

Discussing the multisensory activity of the human brain, SCHÖNHAMMER notes:

[Ein Dogma der Neurologie besagt(e), dass es keine direkten Verbindungen zwischen den primären bzw. sekundären sensorischen Arealen der verschiedenen Modalitäten gebe. […] Ableitungen der Hirnströme an der Schädeldecke ([…]) und bildgebende Verfahren zeigen für das menschliche Hirn zumindest, dass Bereiche, die man früher als monosensuell betrachtete, offen für die Stimulation durch andere Sinne sind.]»48

Therefore, there are neurons that bear upon one kind of sensory perception, for instance, sight. However, the same neurons are capable of cooperating with neurons involved in another kind of sensory perception, for instance, hearing. Moreover, multisensory neurons also exist in the human brain:

[Querverbindungen zwischen den Sinnen existierennicht erst auf kortikaler Ebene . In einem Gebiet im Mittelhirn (densuperioren Colliculi ), das (auch bei Menschen) eine entscheidende Rolle bei derBlicksteuerung bzw.aufmerksamen Zuwendung spielt, wurden zunächst bei Katzen und später auch bei Affen multisensorische Neurone entdeckt, die die gegenseitige, raumbezogene Sensibilisierung von Fühlen, Sehen und Hören vermitteln. Die Aktivität der multimodalen Neurone übersteigt dann, wenn nicht nur einer der Zuflüsse aktiviert ist, die Summe der Einzelregungen: Es geht sozusagen die Post ab, wenn irgendwo zugleich etwas zu sehen und zu hören ist; […].]»49

If two or more different stimuli become effective, then the various sensory perception systems of the legal actors are involved.

2.1.1.2.1.

«Law»: A First Definition ^

To determine «law,» the following reflections draw upon three discourses: legal theory, legal informatics, and popular legal culture.

The term «law» is subject to controversial discussion. Moreover, «law» and «jurisprudence» (Rechtswissenschaft) are distinguished, for example, as follows:

[Recht und Rechtswissenschaft sind zweierlei. Alle Gesellschaften haben Recht, d.h. Vorstellungen vom gebotenen Verhalten, deren Einhaltung mit einer von vornherein absehbaren, mit dem Regelbruch gesetzesmässig verknüpften Zwangssanktion bewehrt ist. Beim Recht handelt es sich insofern um eine anthropologische Konstante. Aber nicht alle Gesellschaften haben auch eine Rechtswissenschaft. Rechtswissenschaft entsteht erst, sobald eine Gesellschaft über einen Bestand an rechtlichen Normen verfügt, der aufgrund Umfang und Komplexität nach einer Fixierung verlangt.]»50

LACHMAYER also distinguishes between law and jurisprudence. While he characterizes jurisprudence as «a meta-system of the law [Metasystem zum Recht],» he observes that «admittedly, the areas are separated only ideal-typically; in fact, they are interwoven most tightly [die Bereiche freilich nur idealtypisch getrennt, tatsächlich […] auf das engste miteinander verflochten [sind.]]»51 The plausible distinction of both legal spheres does not correspond to how the scientific discourse on multisensory law understands the term «law,» especially in connection with the «visualization of law» (Rechtsvisualisierung in German), or rather visual law (Visuelles Recht in German). The former term also refers to visualizations of the contents of jurisprudence. In particular, it includes the contents of legal research and teaching. Examples include visualizations of the case-solving method in private law52 or tree structures, such as those developed by MEIER-HAYOZ/FORSTMOSER, to illustrate the different forms of societies.53

Drawing upon language theory, MAHLMANN conclusively demonstrates how a given discursive context crucially determines the meaning of a term.54 This principle also applies to our present case: the discursive context, multisensory law, determines meaning. On this account, «law» covers both the term «law»and «jurisprudence.»

Before introducing formal aspects of «law,» let me mention which aspects receive no in-depth treatment here, even if they are not neglected by those authors whose statements on «law» I partly paraphrase or cite here. I leave aside the legal-philosophical, hence content-related question about the rightness and justness of the law, since this would be too extensive. Other issues beyond the scope of this paper include the history of «law,» why there is law, and what its functions and effects are. However, this does not mean that the aforementioned aspects are irrelevant to multisensory law, particularly to visual law. Consider, for example, the countless historical and modern representations of justice (sculptures, plastics, paintings ofiustitia , and so forth).

Let me turn to some formal aspects of the law from the perspective of legal theory: while lawyers do not agree on any single description of the term, they give different answers to the meaning of «law,» or what the law is.55 Some voices even doubt whether it is at all possible to define «law.»56 Nevertheless, there are numerous examples of such answers.57 In what follows, I refer to various understandings of «law,» as relevant hereafter. I supplement these notions of «law» with insights from the doctrine of legal sources, especially since these form part of the concept of law in multisensory law.

KOLLER, for instance, formulates the following demands with respect to «law»:

[Zunächst einmal ist soviel klar, dass jedes geltende Recht in Gestalt von sozialen Normen in Erscheinung tritt, die in der sozialen Realität tatsächlich existieren. […] Daraus ergibt sich eine erste Anforderung an den Rechtsbegriff: Die Normen, die in einer Gesellschaft als Recht gelten, müssen sich in irgendwelchen realen Tatsachen manifestieren, die der Erfahrung zugänglich sind. Und das bedeutet wiederum, dass ein annehmbarer Begriff des Rechts jedenfalls eine Bezugnahme auf gewisse faktische Merkmale enthalten muss, […], etwa die autoritative Gesetztheit, […].]»58

Further, KOLLER claims that the concept of law «must delimit the law from other social norms [dass er das Recht von anderen sozialen Normen abgrenzen muss.]»59 He also mentions the criterion «of coercion, with which legal norms are linked [des Zwangs, mit dem die Normen des Rechts verbunden sind.]»60 His third requirement for the concept of law concerns its contents, and is therefore omitted here. For my present concerns, KOLLER’S first requirement is relevant, namely, the law as «being authoritatively ruled [autoritative Gesetztheit].»61 This refers to state legislation.

RÜTHERS/FISCHER tackle the problem of defining «law» as follows: «In the following, the sum of the norms in force, in other words, [the sum of] the norms decreed by the legislator or applied by the courts (court enabled [norms]) are declared law. [Als Recht wird im Folgenden die Summe der geltenden, d.h. vom Gesetzgeber erlassenen und/oder vor den Gerichten angewendeten («gerichtsfähigen») Normen bezeichnet.]»62 According to RÜTHERS, «the cautiously chosen formulation of «applied» law also includes norms in the concept of law that have not been decreed by the state [[schliesst] die vorsichtig gewählte Formulierung vom «angewendeten» Recht auch solche Normen in den Rechtsbegriff ein, die nicht vom Staat gesetzt worden sind.]»63 It strikes me that neither RÜTHERS/ FISCHER nor RÖHL/RÖHL refer to executive bodies in their description of «law.» Hence, it is not fully exhaustive, particularly since executive bodies also apply the law in a democratic state in which the rule of law prevails. Thus, a preliminary finding would be that «law» can be described as the sum of the norms in force – being either ruled or recognized by the state – that judiciary and executive bodies apply.

For RÜTHERS/FISCHER, state recognition includes the inner-state recognition procedure. This forms part of a procedure involving the conclusion of state treaties and aimed at approving such international conventions.64 Based on SEELMANN, I would like to add two further aspects of the concept of law:

[Nicht gemeint ist zunächst, Recht sei identisch mit den vom Staat verordneten Gesetzen. Dieser «Gesetzespositivismus» wird im 20. Jahrhundert soweit ersichtlich von niemandem vertreten – dass zum Recht jedenfalls auch Richterrecht und Gewohnheitsrecht gehören, würde heute niemand ernstlich bestreiten.]»65

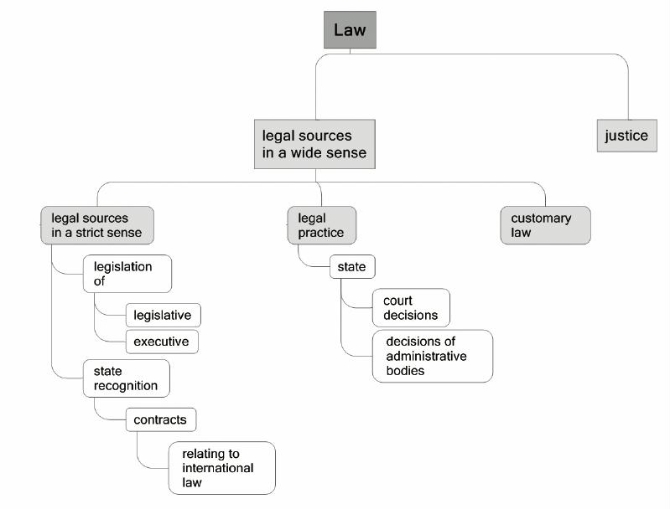

In the light of the above, the following real definition of «law» can be advanced: together with justice, customary law, and judge-made law (case law), the sum of legal norms in force constitute the law. These norms are either decreed or recognized by the state, and applied by its judiciary, government, and administrative bodies.

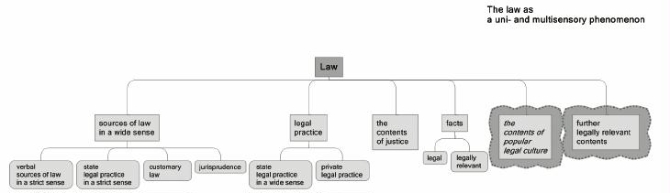

As regards the visualization of law’s real definition (figure 2 ), I have integrated the phrases «legal sources in a wide sense» and «legal sources in a strict sense» in order to elucidate and systematize the elements of this definition. «Legal sources» can be understood as the «place where positive law in force can be found [Fundort für positives, geltendes Recht. ]»66 In doing so, I assume a broad understanding of «legal sources.» What does this mean? Not only does such an understanding include legal norms, «which address anindefinite number of addressees and encompass anindefinite number of cases ([…]) [die sich an eineunbestimmte Anzahl von Adressaten richten und eineunbestimmte Zahl von Fällen erfassen ([…])]»67 (legal sources in a strict sense). It also refers to state legal practice and customary law (that is, legal sources in a wide sense). This procedure coincides with the distinction that RÜTHERS/FISCHER make between «law» and «legal sources»:

[Es geht in der Rechtsquellenlehre darum, (Erkenntnis-)Kriterien zur Ermittlung dessen, was das Recht ist, zu bestimmen. Sie hängt daher direkt mit dem Begriff des Rechts zusammen ([…]), da Rechtsquelle nur das sein kann, was zuvor als Recht anerkannt wurde.]»68

As far as possible, I seek to remedy the weaknesses of the first attempt to provide a real definition of «law,» namely, with the help of insights from legal theory regarding the doctrine of legal sources. I also draw on insights from legal informatics, that is, legal information management, and popular legal culture.69

As an approach within legal informatics, legal information management considers «the law, its production and application as an informational phenomenon [das Recht, seine Produktion und Anwendung als informationelles Phänomen.]»70 While I adopt BERGMAN’S creation of categories71 talis qualis below, I slightly modify and expand his approach.

- The missing components of the legal sources in a wide sense: a) state legal practice in a strict sense:72 this comprises not only decisions of courts and administrative bodies but, for instance, also contracts between (Swiss) cantons or between (German or Austrian) federal states; b) legal research and legal training.

- Other missing components include:

- legal practice in a wide sense:

- state legal practice in a wide sense:

- On the one hand, such practice includes entries in a register, for example, entries in the register of births, deaths, and marriages, as well as entries in commercial and land registers.73

- On the other hand, it includes state legal information management of the legislative, the executive, and the judicial branches. Thus, the three state authorities provide information about legal contents that are relevant to their domain, whether in traditional print form or with the help of the new information and communication technologies. Legislative organs, for example, provide information about legal decrees subject to public ballots. Courts, for instance, provide information about their jurisdiction and proceedings.

- Private legal practice: The first attempt to create a real definition of «law» does not include private legal practice. The latter includes legal transactions and the legal information management of natural and legal persons.

- As regards legal transactions, these are unilateral (wills, foundations, powers of attorney, and so forth), bilateral (contracts), or multilateral (founding of companies, general assembly decisions of legal persons, et cetera).74

- The legal information management of natural persons (for instance, lawyers and trustees) or of legal persons (for example, banks, insurances, trust companies, law firms) bears on legal or legally relevant contents about which these persons mainly inform their customers (clients) and other third parties.

- state legal practice in a wide sense:

- Nor does the first attempt to develop a real definition of «law» cover legal or legally relevant facts (of a case).

- The same applies to ideas, opinions, values, attitudes held by people, particularly by lay persons, with respect to the law and to justice. Scho-lars of popular legal culture, like FRIEDMAN, highlight these aspects:

- legal practice in a wide sense:

«By legal culture I mean nothing more than the ‹ideas, attitudes, values, and opinions about law held by people in a society.› Everyone in a society has ideas and attitudes, and about a range of subjects – education, crime, the economic system, gender relations, religion. Legal culture refers to those ideas and attitudes which are specifically legal in content – ideas about courts, justice, the police, the Supreme Court, lawyers, and so on. (Obviously, one aspect of legal culture is what problems and institutions are defined as legal in the first place.) The term popular culture, on the other hand, refers first, and more generally, to the norms and values held by ordinary people, or at any rate, by non-intellectuals, as opposed to high culture, the culture of intellectuals and the intelligentsia, […] One can also use the term in a second sense, that is to refer to books, songs, movies, plays and TV shows which are about law or lawyers, and which are aimed at a general audience.»75

All these additional aspects carry weight for multisensory law and its branches, such as visual law and audiovisual law. The aspects mentioned in 1 a) and b) and those mentioned in 2 a) and b) rest upon legal theory and legal informatics, that is, legal information management (legal information management is an area within legal informatics). In 2 c), these aspects are extended with an aspect of popular legal culture. Thus far based on legal theory and legal information management, the concept of law can also be tied to the discourse of popular legal culture. Legal information films, broadcast by television companies, thereby move into the focus of multisensory law or rather audiovisual law. The same applies to legal or legally relevant feature films, documentary films, and their mixed forms.

The last missing component of 2) includes:

- Further legally relevant contents: the first attempt to create a real definition of «law» lacks «legally relevant contents» as components. These contents cannot be subsumed under the categories of «law» hitherto enumerated.

2.1.1.2.2.

«Law»: A Second Definition ^

Based on the above, the real definition of «law» needs to be modified. Law encompasses the following components:

- Legal sources in a wide sense:

- Legal sources in a strict sense: the sum of the legal norms in force – either decreed by the state (statutory law) or state recognized (contracts between states related to international law);

- State legal practice in a strict sense: the judge-made law (case law), therefore court decisions and decisions of administrative bodies, as well as contracts between (Swiss) cantons or between (German or Austrian) federal states;

- Customary law;

- Jurisprudence, that is, legal research and education.

- Legal practice:

- State legal practice in a wide sense:

- On the one hand, such practice includes entries in a register, for example, entries in the register of births, deaths, and marriages, as well as entries in commercial and land registers.

- On the other hand, it includes state legal information management of the legislative, the executive, and the judicial branches. Thus, the three state authorities provide information about legal contents that are relevant to their domain, whether in traditional print form or with the help of the new information and communication technologies. Legislative bodies, for example, provide information about legal decrees subject to public ballots. Courts, for instance, provide information about their jurisdiction and proceedings.

- Private legal practice: this includes legal transactions and the legal information management of natural and legal persons.

- As regards legal transactions, these are unilateral (wills, foundations, powers of attorney, and so forth), bilateral (contracts), or multilateral (founding of companies, general assembly decisions of legal persons, et cetera).

- The legal information management of natural persons (for instance, lawyers and trustees) or of legal persons (for example, banks, insurances, trust companies, law firms) bears upon legal or legally relevant contents about which these persons mainly inform their customers (clients) and other third parties.

- State legal practice in a wide sense:

- The contents of justice;

- Legal or legally relevant facts (of a case);

- The contents of popular legal culture, in other words, ideas, opinions, values, attitudes held by people, particularly by lay persons with respect to the law and to justice;

- Further legally relevant contents: these comprise the remaining legally relevant contents which cannot be subsumed under the categories of «law» hitherto enumerated.

2.1.1.3.

«Multisensory Law» ^

Following the real definitions of «multisensory» and «law,» let us turn to their interrelation. Modifying the noun «law,» the adjective «multisensory» refers to which kind of law or which law is at stake. The law in question is not, for instance, copyright law, family law, or penal law, but another legal discipline, that is, multisensory law. The term «multisensory law» not only has terminological implications, but also concerns its subject matter and cognitive interest.

2.1.2.

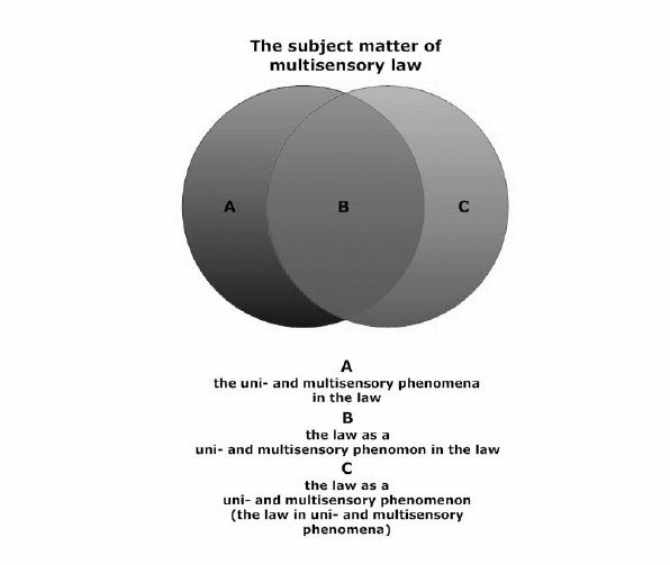

Multisensory Law and its Subject Matter ^

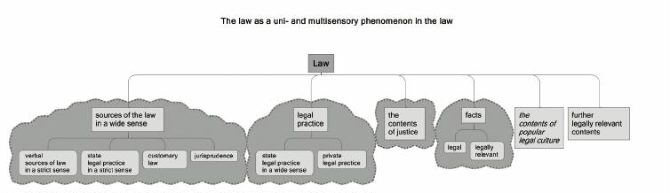

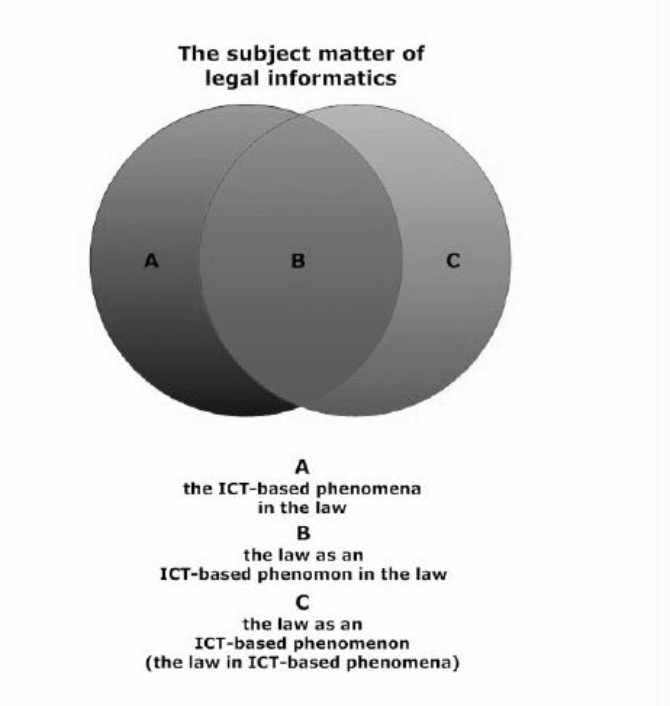

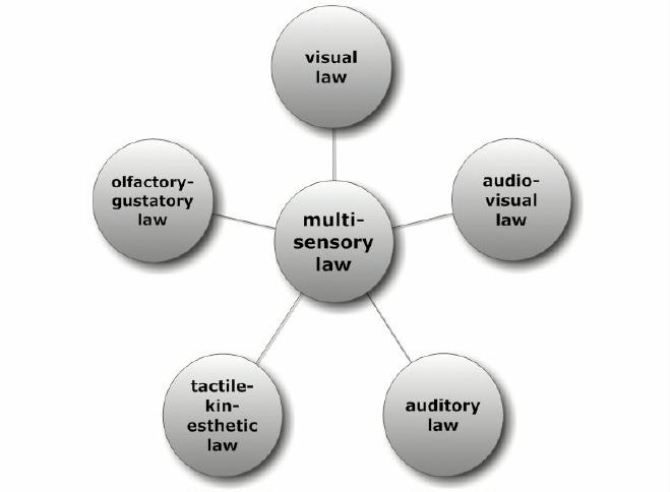

What is the subject matter of multisensory law? This legal discipline brings together the uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law and the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon (that is, the law in uni- and multisensory phenomena). Thus, the subject matter of multisensory law consists of three phenomena deserving further commentary: first, the uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law; second, the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law; and third, the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon (see figure 3).

2.1.2.1.

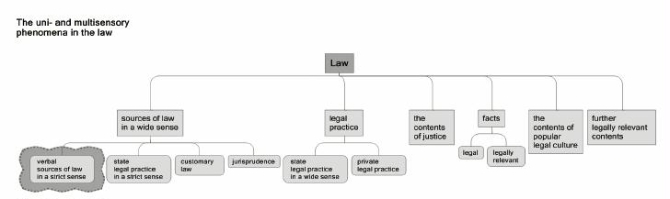

The Uni- and Multisensory Phenomena in the Law ^

Uni- and multisensory phenomena occur in the law. Here, «law» refers to the sources of law in a strict sense (seefigure 4 ).76 «Law» thus includes the legislation of legislative, executive, and state-recognized contracts relating to international law. Consequently, the law in a strict sense rules or governs uni- and multisensory phenomena. Importantly, these phenomena are predominantlyverbally ruled, that is, by the written word.

First example: § 48 Section 1 of the Rule of Procedure of the German Bundestag [Geschäftsordnung des Deutschen Bundestages] reads: «Members of Parliament shall vote by using hand gestures, or by rising from their seats or remaining seated. At the final vote on draft laws, the vote shall be made through standing up or remaining seated. [Abgestimmt wird durch Handzeichen oder durch Aufstehen oder Sitzenbleiben. Bei der Schlussabstimmung über Gesetzesentwürfe (§ 86) erfolgt die Abstimmung durch Aufstehen oder Sitzenbleiben.]» This norm involves visual-tactile-kinesthetic phenomena in particular.

Second example: another visual-tactile-kinesthetic, and thus multisensory phenomenon in the law, § 426 of the Austrian Civil Code [Allgemeines Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch] reads: «As a rule, movable objects can only be transferred by physically changing hands, from hand to another. [Bewegliche Sachen können in der Regel nur durch körperliche Übergabe von Hand zu Hand an einen Andern übertragen werden.]»

Third example: article 43 of the Swiss Victim Support Act [Bundesgesetz über die Hilfe an Opfer von Straftaten (Opferhilfegesetz)] relates to the questioning of children. Section 5 of this article reads: «Questioning shall take place in a suitable room. It shall be recorded on video. The person conducting the questioning and the specialist shall record their particular observations in a report. [Die Einvernahme erfolgt in einem geeigneten Raum. Sie wird auf Video aufgenommen. Die befragende Person und die Spezialistin oder der Spezialist halten ihre besonderen Beobachtungen in einem Bericht fest.]» Section 5 of article 43 also addresses an audiovisual phenomenon relevant to audiovisual evidence.

2.1.2.2.

The Law as a Uni- and Multisensory Phenomenon in the Law ^

The law appears as a uni- or multisensory phenomenon. Its foundations include sources of the law in a wide sense, legal practice, justice-related contents, and legal or legally relevant facts. These foundations are part of the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law (seefigure 5 ). One could also speak of the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the legal context.

First example: the law as a multisensory (audiovisual) phenomenon in state legal practice in a strict sense. In 2009, the Zurich Higher Court [Zürcher Obergericht] video-broadcast a murder trial live to a lecture hall at the University of Zurich because at the time the court was located in a temporary building whose rooms did not provide enough space for the public.77 § 135 Section 1 of the Judicature Act of the Canton of Zurich [Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz des Kantons Zürich], which served as the legal basis for this audiovisual phenomenon, reads: «The hearings and verbal pronouncing of rulings and verdicts shall be public at all courts; at the Higher Court and the Court of Cassation this also includes the deliberation of the decision. Visual and auditive recordings are inadmissible. [Die Verhandlungen und die mündliche Eröffnung der Entscheide sind bei allen Gerichten öffentlich, am Obergericht auch und am Kassationsgericht auch die Urteilsberatungen. Bild- und Tonaufnahmen sind unzulässig.]» Apparently, the Zurich Higher Court had to interpret this verbal norm to legitimate its audiovisual practice, which would otherwise have been illegal.

Second example: the law as a multisensory (audiovisual) phenomenon in jurisprudence. This includes legal education films, such as those broadcast on TELE-JURA78 or «films expressly intended to instruct law students or practicing lawyers in advocacy skills or the finer points of client representation.»79

Third example: the law as a multisensory (audiovisual) phenomenon in state legal practice in a wide sense. One relevant example is the (American) Federal Judicial Center, which offers a video introduction to the patent system. According to the Center’s website, this video

Such mindfulness or meditation practices include an «Awareness of Breath»83 and an «Awareness of Bodily Sensations.»84 Within the scope of this paper, I leave aside RISKIN’S other meditation exercises («Awareness of Thoughts» and «Awareness of Emotions»).85 Discussing in-depth the breathing and body scan meditations for lawyers, he describes meditation on the breath thus:

As mindfulness, or rather the law as a tactile-kinesthetic phenomenon, is also taught at law schools,87 it could also be associated with the law as a tactile-kinesthetic phenomenon in jurisprudence, or more specifically, in legal training.

Thefifth example stems from the U.S. Army context. Currently, U.S. military lawyers have to represent clients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder due to their traumatizing experiences in the Iraq and Afghan wars. SEAMONE observes:

SEAMONE suggests that military attorneys could, or rather should, respond to their clients» stress, for example, by guiding them through breathing exercises.89 Given SEAMONE’S highly welcome advance toward client well-being, we need to consider whether mindfulness would also make sense for clients. Given a client’s prior consent and an agreed time frame90 – after all, lawyers arenot therapists –, they could help clients express their economic and legal interests and their related emotional needs both more effectively and more efficiently.

Sixth example: the law as a uni- and multisensory (visual and audiovisual) phenomenon in the form of legal or legally relevant facts. This involves considering visual and audiovisual evidence brought before a court in civil and criminal proceedings.91

2.1.2.3.

The Law as a Uni- and Multisensory Phenomenon ^

The law appears as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon. Below, «law» refers to the contents of popular legal culture and to further legally relevant contents (seefigure 6 ). Since the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon does not really find itselfin the law, as it was described above,92 one is tempted to perceive it as extraneous to the legal context. Nevertheless, the connections between the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon and the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law are so strong that such a view would not really comply with legal reality, especially as regards the visual and audiovisual contents of popular culture, which tend to be assimilated by legal practice (I return to this point later).

The following three examples refer to the visual and audiovisual contents of popular legal culture:

First example: as mentioned, motion pictures as well as TV movies and shows convey «ideas, attitudes, values, and opinions about law» and lawyers «held by people in a society,»93 particularly by laypersons. According to SHERWIN, such films «help us to provide a basis for empirically testing popular beliefs and opinions about law, lawyers, and the legal system.»94 Further, they «provide an opportunity to show changes in cultural climate, including shifts in shared values, pre-ferences, beliefs, and mood.»95 They «can serve as a springboard to «corrective critique» provided that legal scholars point out popular misconceptions and mistakes about law and its processes.»96 And they «may be used as an aid in law teaching, whether it concerns doctrinal law, insights into visual storytelling practices, or legal ethics.»97 SHERWIN also observes that there is an «interpenetration of popular culture and law.»98 This means that «law’s stories and images migrate from the courtroom to the court of public opinion, and from movie, television, and computer screens back to electronic monitors inside the courtroom itself.»99 SHERWIN demonstrates that the visual and audiovisual contents of popular legal culture can «spill over» onto state legal practice in a strict sense:

Third example : visual and audiovisual litigation PR, as a further instance of the visual and audiovisual contents of popular legal culture. Why? By using the visual and audiovisual public media, the involved parties audiovisually design their own views on the case and thereby seek to affect the outcome of legal proceedings. In criminal proceedings, for instance, the defense counsel endeavors to draw a positive picture of his or her client on television to influence the «Court of Public Opinion .»103 In turn, this might subsequently positively influence the decision taken by the judge(s) or jury.104 Especially in commercial criminal proceedings, the purpose of ligation PR is to uphold the defendant’s reputation in the critical and suspicious eyes of the public, and thereby safeguard his or her socio-economic existence.105 There is, of course, a debate on whether a judge might be influenced by visual and audiovisual litigation PR, and if so how. Judge KOPPENHÖFER, who presided over the famous MANNESMANN case in Germany, observed in an interview that judges are mostly influenced by jurisdiction and literature – and hopefullynot by the media.106

2.1.3.

The Cognitive Interest of Multisensory Law ^

It makes sense to formulate the cognitive interest of multisensory law in terms of various key questions. BENTLY, for instance, asks: «How does law sense? What does law understand to be the nature of our senses? How does law constitute our notions of the senses? How does law control or regulate our senses? How does law use our senses? Which senses does law use?»107 To me, it seems appropriate to formulate the cognitive interest of multisensory law in terms of uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law, the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law, and the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon. These epistemological questions could also be raised with respect to the history of law, but this would go beyond the scope of this paper. Nevertheless, I encourage legal historians to tackle these questions.

2.1.3.1.

The Cognitive Interest of the Uni- and Multisensory Phenomena in the Law ^

The key questions about the uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law in a strict sense include:

- In which verbal sources of the law in a strict sense do these phenomena appear (de lege lata ), or in which sources should they appear (de lege ferenda )?

2. Which problems and questions relating to the uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law in a strict sense do the established disciplines of applicable law and the basic legal disciplines address? - How does legal practice deal with these phenomena?

- As regards the uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law in a strict sense, with which problems and related questions is or should multisensory law be concerned?

- How is multisensory law related to other established legal disciplines and legal practice? That is, how could such disciplines as well as practice benefit from multisensory law as regards the uni- and multisensory phenomena in the law in a strict sense?

Google Street View serves as an example of the fifth question: as might be generally known, Google Street View (which features Google Maps and Google Earth) visually records, saves, and posts online innumerable images of streets, buildings, places, spaces, and space-related objects around the world. Google Street View means that the photographed house numbers, persons, and cars (and their license plates) are placed on the visual record and made public.108

Google Street View is a relatively new phenomenon (it was launched in the United States in 2007).109 How can this technology be assessed in legal terms? It is particularly necessary to consider the pictures taken and their publication online under existing data protection law.110 It would go beyond the scope of this paper to report how data protection laws around the world have answered this question. Since I am a Swiss lawyer, I focus on Swiss data protection law. I also consider publications referring to German data protection law. Even under Swiss law, it is not possible to thoroughly analyze Google Street View. Therefore, I concentrate on how Swiss data protection law deals with the conflict of interest between GOOGLE’S legal interests and the personal rights of those affected. What are GOOGLE’S legal obligations, or rather which obligations should it have in this respect? I support BAERISWYL’S view that Swiss data protection law is applicable to Google Street View.111 Further, I follow his suggestions that the images of persons, license plates, and house numbers are person-related data even if taken on or from public ground.112 According to Art. 3 lit. a of the Swiss Federal Data Protection Law [Bundesgesetz über den Datenschutz], person-related data include «all information relating to a specific or determinable person [alle Angaben, die sich auf eine bestimmte oder bestimmbare Person beziehen.]»

[Bei Fotoaufnahmen in Strassen werden insbesondere auch Personen, Häuser und Fahrzeuge aufgenommen. Damit wird eine Person entweder direkt identifiziert oder als Eigentümer eines Hauses oder eines Fahrzeuges bestimmbar. Es spielt keine Rolle, ob die Person tatsächlich identifiziert wird, sondern es genügt, dass ihre Identifikation aufgrund der Umstände für irgendeinen Dritten mit verhältnismässigem Aufwand möglich wird.]»113

Therefore, anyone processing personal data is prohibited from invading personal privacy (Art. 12 Swiss Federal Data Protection Law [Bundesgesetz über den Datenschutz]). BAERISWYL shows both clearly and plausibly which legal requirements GOOGLE currently fails to meet in full. He therefore considers GOOGLE’S processing of personal data unlawful.114 He refutes the idea that GOOGLE’S private interest overrides that of other private persons:

[Während angenommen werden kann, dass ein nicht personenbezogener Zweck am Ursprung der Anwendung «Street View» steht, kann in Bezug auf die Veröffentlichung nicht von einer ausreichenden Anonymisierung ausgegangen werden. Einerseits lassen sich Personen oder Fahrzeughalter auch aus den Umständen bestimmen, wenn ihre Gesichter oder die Fahrzeugnummern verwischt sind. Andererseits sind allein stehende Liegenschaften oder Liegenschaften mit Hausnummern ohne unverhältnismässigen Aufwand einer bestimmten Person («Eigentümer») zuordenbar. Mithin ist das Konzept der personenbezogenen Aufnahmen mit der nachträglichen Verwischung von Gesichtern und Fahrzeugkennzeichen nicht geeignet, um die Voraussetzungen dieses Rechtfertigungsgrundes zu erfüllen. Vielmehr müsste die Anonymisierung gezielter erfolgen, indem die gesamten Umstände der Bestimmbarkeit berücksichtigt werden, was dazu führen würde, dass auf bestimmte Aufnahmen zu verzichten wäre.]»115

Like THÜR, STUDER distinguishes between anonymizing and rendering unrecognizable those affected by Google Street View. As regards the blurring of persons, he claims that, «strictly speaking, this should probably cover the entire human figure, including an individual’s gait and clothing. [[Unkenntlichmachung ], die streng genommen wohl auch die ganze menschliche Figur mit Gang und Kleidung miterfassen müsste.]»116

By contrast, BAERISWYL observes:

[Möchte sich Google auf den Rechtfertigungsgrund der nicht personenbezogenen Datenbearbeitung stützen, müsste das Konzept der Anonymisierung geändert werden, indem auch nach den Umständen bestimmbare Personendaten gelöscht würden. Des Weiteren wären Hausnummern und Liegenschaften, die klar bestimmbar auf Eigentümer schliessen lassen, vom Dienst auszunehmen.]»117

Further-reaching solutions have been suggested in Germany. Filing an amendment of the Federal Data Protection Law [Bundesdatenschutzgesetz],118 the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, for instance, proposed that § 28 should contain an amended section 4a that would entitle real estate owners or tenants to request GOOGLE to make unrecognizable their building. The same should apply to persons.119

As multisensory law or rather its branches (visual law and audiovisual law) are concerned with the production of legal or legally relevant images, and with legal or legally relevant images as products, they might contribute to the debate on Google Street View by explaining why the sensitive visual elements should be made completely unrecognizable and how this could, or should, be done. Visual elements are recognizable not only from context but also in themselves. Individuals, for example, are recognizable by their clothing, posture, gestures, and their facial expression; houses, for example, by their form, façade, including color, material, size, and so forth. Strikingly, no concrete suggestion so far exists how GOOGLE should improve its Street View technology. To develop a solution capable of satisfying both GOOGLE’S legal and underlying economic interests and the personal rights of those affected,120 distinctions should be made between houses, persons, and vehicles. Reference should be made to the three modes of digitally altering an image: first, deleting one or more visual elements; second, modifying one or more visual elements without adding other elements; and third, modifying visual elements by adding other elements.

At present, GOOGLE modifies one or more visual elements without adding other elements while blurring faces and license plates, or rather while being prepared to do so upon request, in order to reduce the details of these visual elements and to render them hazy, and hence unrecognizable.121

As regards persons and cars, I suggest removing them with a specific feature that, for instance, Adobe Photoshop CS5 provides. This is called «Content-Aware Fill»: «Remove any image detail or object and watch as Content-Aware Fill magically fills in the space left behind. This breakthrough technology matches lighting, tone, and noise so it looks as if the removed content never existed.»122 Further, we need to consider whether the requirements of data protection laws would be met by modifying houses by adding other elements, for instance, color. Houses could be painted over, whereas the opacity of the color could be slightly reduced so that they would remain recognizable as houses but not those of certain persons. From GOOGLE’S perspective, it is important for Street View to include houses, because displaying streets without this feature would not make any sense. If technically feasible, the two solutions should be implemented when taking the pictures. I am fully aware that these suggestions need to be examined by both GOOGLE and data protection agencies. Besides, other solutions requiring close scrutiny might exist.

2.1.3.2.

The Cognitive Interest of the Law as a Uni- and Multisensory Phenomenon in the Law ^

What are the key questions relating to the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law?

- How does the law appear as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law, or how should it appear?

- Do the established disciplines of the applicable law and the basic legal disciplines study the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law? If so, which problems and related questions do they solve and which do they not?

- The same question applies to legal practice.

- As regards the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law, which problems and related questions does multisensory law tackle or should it tackle?

- How could or rather should multisensory law as a new legal discipline contribute to enriching the discourse on the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon in the law within established jurisprudence and legal practice?

One example (from de lege ferenda) for the question raised in (1) concerns future court videos conveying legal information to both laypersons and lawyers. These videos would have a legal basis that would, for instance, rule the contents and objectives of these legal information videos. Multisensory law could help establish which provisions these legal foundations should contain with regard to legal information films. Further, multisensory law could provide expert know-how on how to provide such films. For instance, the European e-Justice Portal provides verbocentric access to much legal information.123 The online television newsroom of The Council of the European Union offers audiovisual legal information relating to e-justice.124

One example of the question raised in (5) is Kelly v. California : by way of background, I refer to my recent review of AUSTIN’S «Documentation, Documentary, and the Law: What Should be Made of Victim Impact Videos:»

InKelly v. California , a victim impact evidence video was introduced in the penalty phase of DOUGLAS KELLY’S trial.126 This film depicts the life of KELLY’S victim, SARA NOKOMIS WEIR, who was raped, robbed, and murdered.127 By way of a closer description of the video, I quote Justice J.P. STEVENS:

Especially the use of music (by ENYA) in this video gave rise to an intense debate. According to Justice J.P. STEVENS, the video «invited a verdict based on sentiment, rather than reasoned judgement.»129 Justice S. BREYER also commented on the emotional impact of the video:

Neither BREYER nor STEVENS draw upon the insights of film studies. Multisensory law might fill this knowledge gap. Specialists in the law of criminal procedure leave this area open, because it appears to lie outside their remit. By contrast, multisensory law also considers the psychological impact of the law as a(n) (audio)visual phenomenon by drawing upon film studies and its insights. Film scholars discuss the (potential) emotionalizing effect of film music:

[Filmmusik dient in der Regel der unterschwelligen Emotionalisierung der Filmhandlung. Gefühle sollen stimuliert werden, man soll sich mit dem Helden identifizieren, sich in Situationen einfühlen. […] Musik kann Erregung verstärken, Stimmung verdichten, ein Lebensgefühl veranschaulichen, aber auch Bilder verbinden und Kontinuität stiften oder als Requisit zur Spannungssteigerung dienen. Das bedeutet, Filmmusik ist nicht autonom, sondern hat eine dienende Funktion, bezogen entweder auf die Handlung, auf einzelne Sequenzen, auf einzelne Figuren und ihr Setting oder auf die Tektonik des ganzen Films, jeweils mit Blick auf den Zuschauer.]»131

FAULSTICH’S reflections urge us to consider whether in«Kelly v. California» the members of the jury identified with SARA NOKOMIS WEIR, the victim. If they did, this most probably contributed to their sentencing the defendant to death. Such awareness would be relevant to other defendants on death row. If a victim impact video uses music for emotional effect, then there is a danger that future jury members will identify with the victim in the penalty phase of the criminal proceedings. Thus, there is a concomitant danger that juries will sentence defendants to death instead of handing down life imprisonment (with or without parole). GORBMAN’S statements on the impact of film music support this view:

Should film music potentially be capable of hypnotizing the spectator-auditor, «inducing a trance,» binding her or him into its narrative world, in the case of victim impact videos, this might jeopardize the defendant’s right to a fair trial.133

2.1.3.3.

The Cognitive Interest of the Law as a Uni- and Multisensory Phenomenon ^

What are the key questions relating to the law as a uni- and multisensory phenomenon?

One example of the question raised in (4) is SCHULTHESS JURISTISCHE MEDIEN, one of the major legal publishers in Switzerland.134 It invites practicing prosecutors, lawyers, police officers, judges, and other legal actors to comment online on a TV series entitled «Tatort» [= crime scene in English].135 From their legal perspective, several experts have already commented on the crimes committed in these TV films, the perpetrators, the victims, and the professional behavior of their «colleagues.»136 These comments are situated at the interface between law and popular culture. For instance, these experts «point out popular misconceptions and mistakes about law and its processes,»137 and thereby make the internet audience aware of those contents of penal law and criminal trial law that are assimilated by the television series, whether incompletely or in a distorted way.

2.1.4.1.

Preliminary Remarks and Working Hypothesis ^

Is multisensory law a new legal discipline? Raising this question leads to a host of related questions: what is science (Wissenschaft)? Does law constitute a science? What is law (Rechtswissenschaft)? Does multisensory law constitute a science of law (Wissenschaft des Rechts)? Which factors play a part in contributing to the emergence of a new branch of science (internal differentiation of science)? Put differently, how does the development of such an internal differentiation occur? If multisensory law is a science of law, does it fulfill the requirements of being a branch of law? Does it therefore qualify as a new legal discipline? If multisensory law constitutes a new legal discipline, does it belong to the established disciplines of the applicable law or to the basic legal disciplines, or does it stand in between? To answer the basic question, we need to raise further questions: does multisensory law constitute a new independent interdisciplinary discipline notintra , butextra muros jurisprudentiae ? If so, what would be its constituent disciplines? Or can multisensory law be merely described as an approach within established legal disciplines? And if so, within which legal disciplines?

Clearly, whether multisensory law is a new legal discipline reaches far beyond this paper. And so do the aforementioned questions. For now, I refer interested readers to the relevant literature. As regards what science is, we have responses from legal theory,138 the theory of science (Wissenschaftstheorie),139 the sociology of science (Wissenschaftssoziologie),140 and the history of science (Wissenschaftsgeschichte).141 These responses support the hypothesis that multisensory law is a science-in-the-making. Legal theory has considered what law (Rechtswissenschaft) is.142 Its insights support the hypothesis that multisensory law is a science of law (in the making). Further, it could be argued that multisensory law is a science of law (in the making) because its subject matter is both legal and legally relevant.

On this basis, I hypothesize that multisensory law constitutes a science-in-the-making and, more specifically, a science of law (eine Wissenschaft des Rechts)in statu nascendi . Below, I outline answers to two questions: 1. Does multisensory law fulfill the requirements of a branch of law and should it hence be qualified as a new legal discipline? 2. Does multisensory law constitute a new independent interdisciplinary discipline notintra , butextra muros jurisprudentiae ? Or can multisensory law be merely described as an approach within established legal disciplines?

2.1.4.2.

Multisensory Law as a Branch of Law? ^

From the perspective of the sociology of science, two essential factors, among others, contribute to the internal differentiation of scholarship. The first concerns the overwhelming flood of scientific literature, which nobody is really able to manage.143 WEINGART, for instance, notes that:

[Wie aber reagiert das Wissenschaftssystem auf den Sachverhalt, dass tatsächlich eine ständig zunehmende Flut an Literatur produziert wird? Wie ist es zu erklären, dass das System funktioniert, […]? Es gibt im wesentlichen zwei miteinander verbundene Mechanismen, durch die das System auf sein eigenes Wachstum reagiert: erstens durch selektive Aufmerksamkeit und zweitens durch Innendifferenzierung. Die selektive Aufmerksamkeit besagt, dass ein Teil der gesamten Menge an produziertem Wissen einfach unbeachtet bleibt. Mehr als die Hälfte aller Publikationen wird nie zitiert, d.h., sie fällt aus dem Kommunikationsprozess heraus ([…]). […] Der zweite Mechanismus, die Innendifferenzierung, ist eine Folge der Selektivität.]»144

This paper leaves no room for bibliometrical measurements of the number of publications explicitly or implicitly dealing with the problems and related questions of multisensory law and its branches. Already in 2009, I limited myself to only the most significant books and papers. Fully aware that this list was not exhaustive, I only listed publications that can be subsumed under visual law and audiovisual law, currently very relevant branches of multisensory law.145 Many more pertinent publications have appeared since, especially in English but also in German.146 Rather than provide a comprehensive list, I refer to the work of scholars who were or are still active, even though their research deals chiefly with visual law and audiovisual law. I consider publications on tactile-kinesthetic law separately. While leaving aside publications already listed in my article «Rechtsvisualisierung [legal visualization]»147 or aforementioned in this paper, I indicate older publications that escaped discovery beforehand but are nevertheless worth mentioning: 1. German publications on visual law and audiovisual law;148 2. English publications on visual law and audiovisual law;149 3. publications on tactile-kinesthetic law, especially onembodied legal teaching and on mindfulness for law students and lawyers.150 To keep abreast of current publications particularly on visual law and audiovisual law, I recommend RÖHL’S/ULBRICH’S blog «Recht anschaulich [Graphic Law]»151 and HOLZER’S legal visualization website.152 Relevant book projects are also underway, such as «Law, Culture, and Visual Studies» (working title)153 and «Beyond Text in Legal Education.»154

WEINGART remarks on the second factor of internal differentiation:

[Zum einen handelt es sich um die Differenzierung nach innen, d.h. die weitergehende Spezialisierung nach Massgabe der selbstreferenziellen Dynamik der Disziplinen. Zum anderen ist es die Expansion der Wissenschaft, also die Verschiebung der institutionellen Grenzen in Bereiche, die zuvor nicht zum Kanon ihrer Gegenstände gehörten. Damit ist nicht nur eine Verwissenschaftlichung der Alltagserfahrung gemeint, sondern es kann sich auch um Bereiche handeln, die neue epistemologische Zugänge erfordern und hergebrachte Unterscheidungen nicht mehr gültig erscheinen lassen.]»155

Closer scrutiny reveals that copious literature discusses the subject matter and cognitive interest of multisensory law and its currently most relevant branches. It is, therefore, doubtful whether the members of the established disciplines of the applicable law and of the legal basic disciplines are able to assimilate this bulk of literature. Consequently, internal differentiations are occurring within law, focusing especially on visual law, audiovisual law, or tactile-kinesthetic law. The subjects of multisensory law are predominantly new. Hence, the law is urgently called upon to develop new insights and to question the present canon of differentiations or classifications as regards its own disciplines.

The sociology of science offers a phase model for the emergence and development of special fields within science and scholarship:

Currently, legal scholars (including legal historians, legal psychologists, legal theorists, legal sociologists, data protection lawyers) and scholars from other disciplines, (including business informatics, e-government, media studies, visual communication (design), film studies) are dealing with the problems and related questions of multisensory law and its branches.

Whether multisensory law is the subject of a scientific communication network eludes a straightforward «yes» or «no.» There is a community on multisensory law at C.H. Beck publishers.158 To date, this community is very small. Nevertheless, a circle of interested people totalling more than a hundred persons accesses the community’s postings.159 The community grew from the Munich Conferences on Multisensory Law.160 Whether, and if so how, it will further develop cannot be foreseen. Role playing, involving sight, touch, and movement, is used as a training method in legal education at law schools. Various scholars are hence exploring this topic.161 Certain branches of multisensory law have recognizable scientific communities. Occasionally, these branches or aspects of these branches are also taught at law schools. In what follows, I cite evidence for these communities.

In recent years, a visual law community has emerged, even though it does not normally refer to itself as such. In the German-speaking world, a conference entitled «Visuelle Rechtskommunikation» (Visual Legal Communication) was held at the Ruhr University of Bochum in 2001.162 Since 2003, legal scholars and practitioners regularly convene to discuss problems and related questions at the Internationales Rechtsinformatik-Symposion (International Conference on Legal Informatics), held at the University of Salzburg, Austria.163 In 2004, a conference on legal visualization (Konferenz zur Rechtsvisualisierung) was organized at the University of Bielefeld, Germany (Center for Interdisciplinary Research), where the German-speaking visual law community met.164 Beyond the German-speaking world, members of this community gather at conferences dedicated to different issues within visual law, including the «International Roundtable for the Semiotics of Law»165 or the conference on «Law and the Image.»166

In audiovisual law, a community has also been established. Similar to visual law, different terms have emerged, for instance «film and law movement.» Meanwhile, this movement covers only a subarea of audiovisual law, at least until now:

A further community in audiovisual law has formed around the «Penn Law’s Visual Legal Advocacy Roundtables,» held at the University of Pennsylvania Law School to discuss legal documentaries. Legal documentaries are law films with both images and sound. Regardless of the too narrow term «visual» in the title of these roundtables, they nevertheless fall under «audiovisual law.» Such law films require not only an analysis of their visual, but also of their acoustic elements, such as spoken words and music, as well as of their interaction with visual elements.168

In tactile-kinesthetic law, communities are also emerging and growing. Again, they run under different names: according to its conference website, «The Mindful Lawyer,» a community «exploring the integration of meditation and contemplative practices with legal education and practices» has emerged.169 This conference offered «a blend of academic presentation, practical experience and discussion, meditation and movement practice, and recent developments in neuroscience and psychology relevant to meditation practice.»170 The following community can be subsumed under the wording «embodied legal teaching and learning.» It takes a stand for a non-verbocentric approach to legal education (Rechtsdidaktik). The latter invites law students «to put their bodies into the learning of law.»171

[Die dritte Phase der Gruppen-(Cluster-)bildung setzt in dem Augenblick ein, in dem sich die Wissenschaftler ihrer Kommunikationsbeziehungen bewusst werden, Grenzen ziehen, nicht zuletzt durch Namensgebung, und damit Identität konstitutieren.]»172

In addition, GALBI continues:

Such reflections might lead scholars to reconsider the terms used so far, since these terms only cover some of the phenomena of multisensory law currently at stake – except, perhaps, «sensational jurisprudence.»

Considering the last phase of the emergence and development of special fields within science and scholarship, WEINGART observes:

[Die letzte Phase schliesslich ist die Bildung eines Spezialgebiets, d.h. die Institutionalisierung regulärer Prozesse der Rekrutierung und Ausbildung, von Mitgliedschaftsprüfungen, Zeitschriften, Konferenzen usw. Die Mitglieder des Gebiets nehmen ihre Arbeiten wechselseitig wahr und verfolgen gemeinsame Fragestellungen […].]»192

As mentioned, conferences, workshops, and symposia on the subject are held on a regular basis. Especially in the United States, various courses and programs deal with aspects of visual law, audiovisual law, and tactile-kinesthetic law. MAUET, for instance, teaches how to use visual aids during trials.193 AUSTIN teaches courses on «Visual Legal Advocacy» and «Documentaries & the Law.»194 SHERWIN teaches courses on «Law & Popular Culture» and «Visual Persuasion in the Law.»195 HALPERN offers a course entitled «Effective and Sustainable Law Practice: The Meditative Perspective» at UC Berkeley School of Law.196 Special meditation courses for law students and legal actors are offered.197

Given all these phenomena, multisensory law begins in phase four. It can therefore be considered a branch of lawin statu nascendi , a new legal discipline in the making.

2.1.4.3.

Multisensory Law as a New Discipline in the Making (intra muros jurisprudentiae) ^

Multisensory law doesnot constitute a new independent interdisciplinary discipline outside the law. The subject matter and cognitive interest of multisensory law solely cover uni- and multisensory legal or legally relevant phenomena. There is no other scientific disciplineextra muros jurisprudentiae that both specifically and predominantly tackles these phenomena.

Primarily in the Anglo-Saxon scientific community, there are so-called «law and» movements, such as the law and humanities movement.198 Even if these «law-and» movements draw on insights gained in extra-juridical disciplines, they are ultimately anchored in the law. For instance, the law and humanities movement deals with important problems and related questions of multisensory law and its branches. Discussing visual law and audiovisual law, SHERWIN asks «What has film to do with law?»199 Raising this basic question in a collection of essays entitled «Law and the Humanities,» where SHERWIN is one the contributing authors, he distinguishes between «law in film» and «law as film.»200

Despite these important interfaces with multisensory law, the law and humanities movement does not fully embraceall the legal and legally relevant issues raised by our different senses. Other disciplines than «just» the humanities contribute or could contribute to resolving these issues. These disciplines range from the humanities through the social sciences to medicine (especially neuroscience) and psychology (especially the psychology of perception and learning psychology).

2.2.1.

«Visual Law» ^

To understand the term «visual law,» we must proceed similarly to «multisensory law.» Hence, I clarify the adjective «visual,» the noun «law,» and how these words are related to each other. Given the above real definition of «law,»201 we need only expand on «visual.»

2.2.1.1.

«Visual» ^

In everyday language, the adjective «visual» («optical») means «pertaining to seeing, the sense of sight.»202 As regards human sight, the psychology of perception distinguishes between the visual stimulus and the responding visual system. Light (electromagnetic radiation) constitutes the visual stimulus.203 The visual system consists of different elements, such as the eye(s) and those areas of the human brain responsible for seeing.204 It would lead too far to sketch the ana-tomy, physiology, and the various processes of the visual system.205 Visual stimuli can be either close or distant to the visual system to be perceived by sight. Sight constitutes a sense for things both close and distant. It can be broken down into external seeing (visual perception of external stimuli) and internal seeing (visual representation). For example, external seeing relates to the following perceptual contents: one’s own body or elements of the external world, such as persons, things, and so forth.206 If we compare external seeing with (internal) visual representation, then various differences become apparent: as a rule, the contents of external perception are more detailed than those of mere (internal) representation. Whereas perceptions come toward us, (internal) representation must be worked for. Mostly, external seeing is connected with body movements. Internal seeing can be performed at physical ease. Further, it can be induced by previous external seeing so that whatever was originally perceived appears in representations (mental images).207 The visual cortex is involved in both external and internal seeing.208

2.2.1.2.

«Visual Law» ^

Following the above real definition of «visual,» how does the noun «law,» as understood here,209 relate to the former term? Modifying the noun «law,» the adjective «visual» tells us what kind of law or which law is at stake.

Similarly to visual law, the above has not only terminological implications, but it also concerns the subject matter and cognitive interest.Mutatis mutandis , the previous reflections on multisensory law could be transferred to visual law. As multisensory law itself and its branches are still new, I would, however, also like to tackle these questions explicitly with respect to visual law. While this implies certain repetitions, I hope it leads to a better understanding of multisensory law and its branch «visual law.»

2.2.2.

The Subject Matter of Visual Law ^

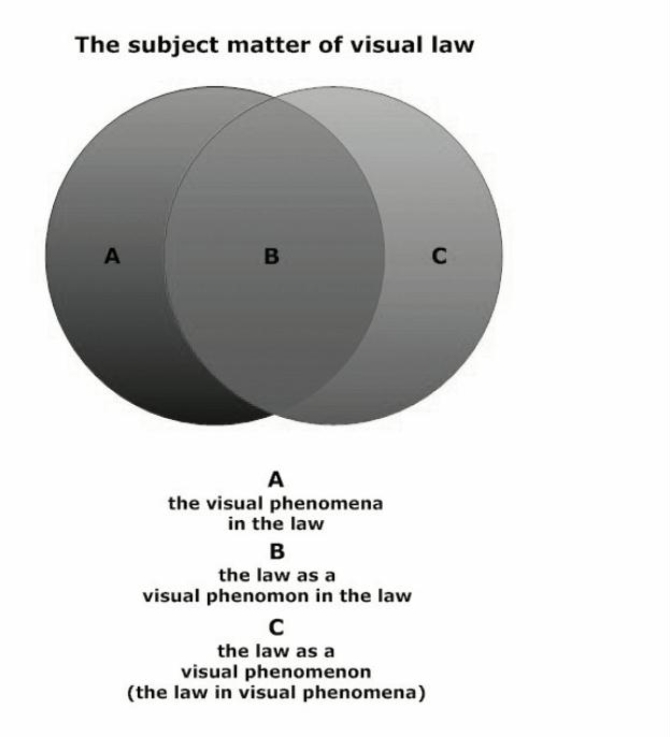

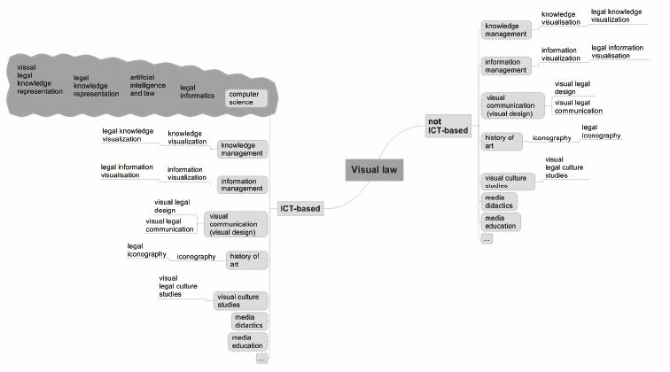

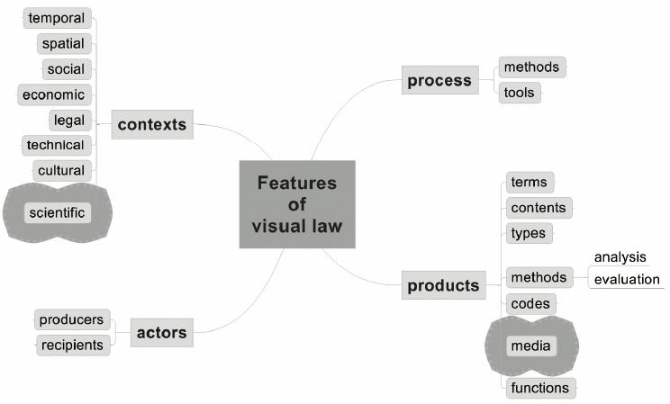

What is the subject matter of visual law? This branch of multisensory law brings together visual phenomena in the law and the law as a visual phenomenon (that is, the law in visual phenomena). Therefore, the subject matter of visual law consists of three phenomena: first, the visual phenomena in the law; second, the law as a visual phenomenon in the law; and third, the law as a visual phenomenon (see figure 7).

2.2.2.1.

The Visual Phenomena in the Law ^

Visual phenomena appear in the law. As stated,210 «law» here means the sources of law in a strict sense. In other words, the legislation of legislative, executive, and state-recognized contracts relating to international law. Thus, the law in a strict sense rules or governs visual phenomena. Again, it is necessary to emphasize that these phenomena areverbally ruled, that is, by the written word.

One case in point is Art. 26 of the 3rd Swiss Labor Law Ordinance [Verordnung 3 zum Arbeitsgesetz]:

[1 Überwachungs- und Kontrollsysteme, die das Verhalten der Arbeitnehmer am Arbeitsplatz überwachen sollen, dürfen nicht eingesetzt werden. 2 Sind Überwachungs- oder Kontrollsysteme aus anderen Gründen erforderlich, so sind sie insbesondere so zu gestalten und anzuordnen, dass die Gesundheit und Bewegungsfreiheit der Arbeitnehmer dadurch nicht beeinträchtigt werden.]»211

Employee surveillance using video cameras can be subsumed under this legal norm.212 Where such video cameras record not only visual, but also auditive data, such as employee voices or other sounds, we can speak of audiovisual phenomena in the law. Thus, we may ask whether Art. 26 provides a sufficient legal basis for these phenomena.213

2.2.2.2.

The Law as a Visual Phenomenon in the Law ^

Besides appearing as a visual phenomenon, the law has a basis in the sources of the law in a wide sense, that is, in legal practice, in justice-related contents, and in legal or legally relevant facts. This is what is meant by the law as a visual phenomenon in the law (seefigure 5 ), or by the law as a visual phenomenon in the legal context.

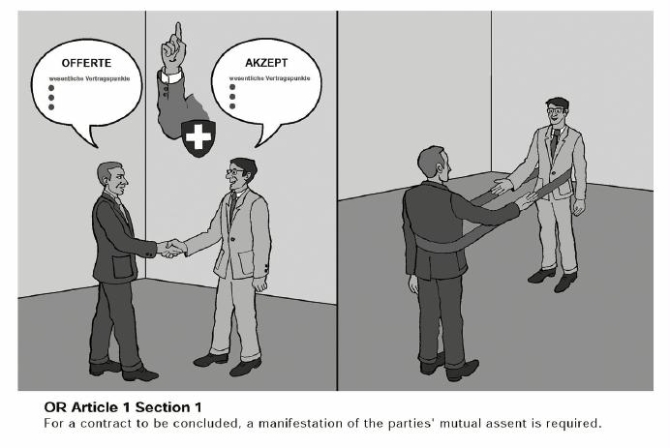

Examples of the law as a visual phenomenon in legal training: (1) My doctoral dissertation on the «Visualization of Legal Norms [Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen],» developed and applied a method for creating so-called legal norm images. One case in point is Article 1 Section 1 of the Swiss Code of Obligations [= Schweizerisches Obligationenrecht]):214

Figure 8215

These legal norm images are used or could be used in (Swiss) legal education or even in private and state legal practice in a wide sense, that is, in state legal information management of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches with a view to both illustrating and explaining the content of the respective legal norms. My visualizations drew upon semiotics and visual communication, and also linked the legal norm images with the tradition of (legal) iconography.216 Supposing there existed a legal basis in the form of a syllabus prescribing the use of legal norm images or other legal visualizations in legal education, or in state legal practice in a strict sense and in a wide sense, or indeed in private legal practice, then this would be an example of both visual phenomena in the law and the law as a visual phenomenon in the law.(2) Starting from the aforementioned study on the visualization of legal norms and expanding it with psychological approaches, WALSER KESSEL/CRESPO explore how children and adolescents visualize legal norms by children.217 Legal norm images drawn by children, adolescents, or adults can or could be used to educate those lacking sufficient knowledge of the law. Hence, I strongly advocate this kind of visual legal education, which would help developvisual legal literacy .218 Furthermore, children and adolescents could be made aware of the «lines drawn by the law» that they are not allowed to cross. For instance, such legal norm images would be aimed at preventing violence among children and adolescents, and among them and adults.219 Such images could help children and adolescents understand what a legal separation or divorce is and which (legal) actors are involved.220 This would support them in coping with their parents» steps toward separation and divorce.(3) In the two-volume «dtv-Atlas Recht» on German law, HILGENDORF visualizes his key statements221 and suggests using them in legal education.222

Examples of the law as a visual phenomenon in state legal practice: (1) Drawing upon insights from logics, linguistics, learning psychology, and educational psychology, ROBINSON presents a logic diagram visualizing tax law issues to be used in an administrative agency, such as the Office of State Revenue, Queensland.223 (2) In the legislation (formation) process, Computer Supported Argument Visualization is used to convey legal information to citizens (whether they are lay persons or lawyers), by visualizing the decree and its norms, law justification reports of state bodies, and expert and political opinions on the bill.224 For instance, IBM has been seeking to visualize legislative bills of the U.S. Federal Legislation.225

Examples of the law as a visual phenomenon in private legal practice: there is a growing body of research on the visualization of contracts in private legal practice.226 While DASKALOPULU’S and SERGOT’S «The Representation of Legal Contracts» merely suggests how to better visualize written contracts, their «paper outlines ongoing research on logic-based tools for the analysis and representation of contracts» by considering «both contract formation and contract performance, in each case identifying representational issues and the prospects for providing automated support tools.»227 Their article thus provides a basic knowledge and know-how of visualizing contracts.

Examples of the law as a visual phenomenon with respect to legal or legally relevant facts: (1) Given the crucial role of arguments in the legal context,228 argument-visualization is used in different areas: WIGMORE, for instance, was among the first to visually present legal or legally relevant facts for the purpose of evidence by proposing «a Chart Method for analysing the mass of evidence presented in a legal case, in order to help the analyst reach a conclusion.»229 Today, various software, such as SmartDraw, helps create WIGMORE charts.230 (2) There are numerous ways of visualizing legal or legally relevant facts. In «Argument Mapping and Storytelling in Criminal Cases,» BEX developed a method combining argument-based with story-based approaches to visualize arguments for evidence purposes.231 However, such legal visualizations appear to lack a specific legal basis.(3) Legal or legally relevant facts can have a basis in the law in a strict sense, for instance, the Federal Rules of Evidence232 : in the United States, animation

These animations

As regards visual evidence, MA/ZHENG/LALLIE observe:

Despite the overwhelming performance of computer-generated animation, the authors make the following reservation, which might be relevant to existing rules of evidence (de lege lata ) or even to future rules of evidence (de lege ferenda ):