1.

Introduction ^

When preparing for legal proceedings in the US, lawyers began listing documents and data of every conceivable category in their discovery requests1 even if these requests were worded so broadly that the documents to be discovered were bound to include numerous files whose relevance to the case at hand was nil or highly unlikely at best. This in turn led counsel of either side to strongly advise their clients in pre-trial meetings to preserve any documents and data even remotely relevant to a case. They further cautioned them against risking any exposure whatsoever to court sanctions for destruction of evidence. (In some US jurisdictions, courts are known to hand down such sanctions whether or not the offending party acted in bad faith2.) The clients were also advised to err on the safe side and disclose too much rather than too little.

The battle lines were quickly drawn. The one camp received backing from the magistrates in the US who ordered documents to be discovered irrespective of European data protection laws, the other from EU data protection bodies such as the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party3. This body issued a working paper4 with demands so far-reaching as to render e-discovering entirely impractical if they were heeded to the letter. Both EU data protection law and US civil procedural law provide scope for weighing up competing interests and so allow for more narrow interpretations of their own underlying principles. At the same time, neither law accords equal status to the interests of the other camp, if indeed these were even a consideration when the laws were drafted.

These efforts are gradually bearing fruit as more and more US judges, counsel and government agencies become aware of the many restrictive provisions of EU data protection legislation which apply to companies and which multinationals cannot ignore at will. Data protection officials for their part have recognised that a firm planning to do business in the US market will have to get familiar with all applicable law of the US legal system sooner or later, just as US companies operating in the EU are subject to the European system. And they do see that some concessions on data protection (including on the right of individuals to have their data erased or rectified), while inevitable, can reasonably be granted without stripping data protection legislation of its essence5.

2.1.

Overview ^

At the legal level, other than the clashes between the divergent philosophies underpinning the US and continental European legal cultures, there are five other major challenges to consider, namely, the extremely vast scope of data protection laws, in geographical reach as in subject matter; the principles of legitimacy, transparency and proportionality; safeguards to protect the rights of data subjects; and the special regulations governing cross-border disclosure of personal data to the US and other countries that – from a European perspective – lack an «adequate» level of protection for personal data.

2.2.1.

Conflicting legal cultures ^

These legal conflicts flow from the divergent traditions in UK-US law versus Continental European law. Under US procedural law, for example, all parties to a legal proceeding assume as a matter of course that each of them will first preserve and gather any data and materials in its own area that could be deemed potentially relevant; then deliver this data and materials to its US legal counsel for review; and finally make the data and materials available to all parties to the legal proceeding – including the opposing party, in other words – for evidentiary purposes. This usually happens during the pre-trial discovery. Although a party could be forced to produce such data and materials, this is normally not necessary. Controversal discussions may typically arise over the scope, timetable and nature of a discovery or of the discovery requests of either party6 which under the US Rules of Civil Procedure the parties should discuss in the meet and confer talks early on7. One consequence of this tradition of producing any documents deemed even remotely relevant (even if damaging) is for instance that many companies now limit the period of (pre-trial) document preservation8 to a minimum: just a few months sometimes, and rarely longer than 18 months. The situation is similar in other common-law countries.

A US court may order a person based in its jurisdiction to disclose a broad spectrum of data this person actually possesses, has in custody or controls, regardless of their physical location9. In such cases, US law does not require compliance with applicable international accords such as the Hague Convention on Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters – not even where the records in question are kept in foreign territory. The judge may subpoena a party to the proceedings to discover its records if it has refused to do so before. This subpoena will stand even if the actual order to disclose foreign-based records is allowed only once the particulars of the case have been considered10. Continental European law does counter these tendencies in US law, which does not necessarily make life easier for a multinational firm. For instance, the laws of various countries, including Switzerland and France, specifically protect the state sovereignty against acts of foreign courts and other public authorities. Under these statutes, the circumvention of the judicial or administrative assistance by privately gathering evidence in these territories may constitute a punishable offence11. Often referred to as blocking statutes, theses laws sometimes prohibit entities from disclosing even their own records in proceedings abroad to which they are party. So where a company is subpoenaed also by the foreign judge to disclose its own records, it will have to choose between two evils – unless it has made timely provisions to steer clear of such a dilemma.

Indeed, most multinationals can generally avoid this dilemma. In Switzerland for example even conservative scholars interpret the relevant legislation – Art. 271 of the Swiss Penal Code (SPC) – to mean that an entity is only prohibited from disclosing own records in proceedings to which it is party if said entity is being ordered (subpoenaed) or forced to do so12. In other words, an entity will not be liable to Swiss prosecution under Art. 271 if disclosing own records as part of a voluntary pre-trial discovery. If however a company refuses a reasonable disclosure request from the opposing party because it is gambling on averting a discovery of damaging records, then that company may simply find itself in deeper trouble later on. This is because a subsequent court-ordered subpoena to discover the records would eliminate the option of discovering them outside the legal assistance procedure even if the company were prepared to do so then – the consequences of which would be worse still. As this scenario illustrates, companies are well advised to look into the potential implications of non-cooperation – under non-US as well as US law – early on. For expediency, some discovery managers will weigh the relative threat of sanctions. In Switzerland for example a discovery manager will find that contravening data protection statutes in a pre-trial discovery tends to invite far less serious sanctions (if any) than violating Art. 271 SPC as a result of a discovery by court order13.

Once a company is in this dilemma, international mutual legal assistance can help resolve only some of the issues involved even if the US judge is willing to provide it. For example, not all countries in Europe are signatories to the aforementioned Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad, and some who are have expressed reservations about disclosing records for the purposes of a discovery14.

Other signatories to the Hague Convention do allow the gathering evidence on a broad scope through mutual legal assistance procedures and they even exclude the applicability of the normal data protection legislation, at least in cases where all parties agree15. Here too, the US perspective requires certain compromises, such as on the time window allowable for the taking of evidence16 or the scope and the standard to be set for its prior specification, which in some cases may exceed the standard set by US law. Likewise, contractual or legal secrecy duties may, if they prohibit discovery in proceedings involving third parties or if they prohibit the export of materials17, put multinationals in a bind, especially if compliance with these duties is secured by criminal law. Such secrecy duties have partially been designed with a specific view to safeguard trade secrets from disclosure abroad18. In such cases, discovering records in US proceedings may render the employees responsible liable to prosecution – at least if no further safeguards19 were taken – even if their employer was ordered by a US court to disclose the records.

In the day-to-day operations of multinationals, however, data protection is the main source of conflict between discovery duties in US civil proceedings and Continental European law. The challenges it involves are discussed below. Data protection in its current form has been with us for many years, but more recently public perception of its merits, and companies' legal compliance, have been growing, while sanctions handed down for breaches have become tougher in various countries20.

2.2.2.

The five legal challenges of data protection ^

2.2.2.1.

First challenge: scope ^

Swiss data protection law is a case in point: it may be applied even if a person whose data are subject to a discovery («data subject») is a permanent resident of Switzerland but his or her data are collected and processed abroad only21. It follows from this that any data gathering which presumably will include the personal data of Swiss residents or Swiss nationals among others will be subject also to Swiss federal data protection statutes, even if all data gathering and processing in connection with an e-discovery occurred or will occur strictly outside of Switzerland. Because Swiss federal data protection statutes extend to legal persons as well – as shown below – it is bound to apply in some form or other to multinationals with significant connections to Switzerland. From a company's legal compliance perspective this means that the firm must be capable either of classifying its data by applicable law or of adopting the strictest of all potentially applicable law (even if applicable only with regard to a subset of the data). In practice multinationals tend to choose the latter option, because data classified by jurisdiction is often unavailable and differentiated compliance therefore is impractical.

Another point to bear in mind is that national data protection statutes extend to any data imported as much as to data created in-country. If for example a Swiss-based parent company preparing for legal proceedings in the US pools personal data from all over Europe (or from Europe and the US) and sends these data on from Switzerland to its legal representatives in the US, then that parent company will have to comply with the substantive national data protection laws that apply to the data collected in each country, plus, for all data, the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection (DPA), which governs any and all data processed by the parent company in Switzerland. This holds true even in cases where the data did not originate in Switzerland but ended up there purely for e-discovery purposes. The data remain subject to substantive Swiss data protection law long after it has been transferred to the US. While not always enforceable in a local court, claims for damages for breaches of data protection in the US may be filed against the parent company and any additional parties involved (such as the parent's legal counsel in the US) in Switzerland as well, even if the data were there only «in transit». Conversely, practical experience has also shown that routing datastreams via certain legal systems can be an advantage if there – as in Switzerland in the above example – the formal requirements for exporting data are less strict than in the bulk of EU member countries. This is because onward exports of personal data from Switzerland as such are in general governed exclusively by Swiss data protection law once the data has been exported to Switzerland.ERR

From a subject matter perspective as well the reach of European-style data protection statutes is extensive. These tend to turn on the concept of «personal data», which refers to all information relating to an identified or identifiable individual22. In some legal systems this concept is defined more narrowly23. In others, it is defined more loosely to include the personal data of legal persons as well as that of natural persons24. This may affect multinationals disproportionately, for example in situations where – as described above – centralised data processing may lead to the same data being subject to the data protection laws of several legal systems at once, thus forcing a multinational to choose between two options: either to adhere to the strictest law applicable (which in the present context would require protecting the data of legal persons as well) or to risk contravening certain national data protection laws (by focusing in-house data protection measures on the data of natural persons). Experience shows that many multinationals opt for the latter and leave it to their local subsidiaries to take more extensive measures if and as needed.

- For one thing, personal data as a concept is often more narrowly defined in US law than it is in practice. (Another term, personally identifiable information, has become popular in the US and, while defined inconsistently, is sometimes used to mean the same as personal data25). It is not uncommon, for instance, for a US court to upon request extend a protective order for safeguarding business secrets in pre-trial discovery data to provide the same protections also to all personal data. Parties will often only later on realize that this means that more or less any and all e-mails, documents and data discovered must be kept confidential. Hardly a document in a pre-trial discovery will ever be entirely free of personal data as defined by European data protection law, except where such a document has been painstakingly anonymised, a practice routinely followed only for sensitive data and even then only selectively. Another common source of misconceptions is confusions of the concepts of personal data and private data. Typically, the former refers to personal data as defined above and as such includes data that, while relating to individuals, are of a business nature nonetheless. Private data by contrast are strictly private personal data; this concept refers to personal data not of a business nature.

- For another, data protection specialists in Europe and trial lawyers in the US frequently think in different categories in their respective areas. European data protection specialists want to regulate the processing of certain types of information as such, wherever and however such processing may occur. US trial lawyers meanwhile focus on the container of information, that is to say the document or dataset within which certain information is contained. Distinguishing as they do between content and carrier or form can be quite relevant, such as when data protection safeguards are being agreed or court-ordered. It is not sufficient to protect only documents as such; the protection must extend beyond to also include any verbal communications and the transfer of information contained in these document to other documents, even if these other documents are not part of the discovery, such as a legal brief or a written court verdict.

2.2.2.2.

Second challenge: legitimate purpose and transparency ^

The next challenge in making e-discovery projects data protection compliant is the principle of legitimate purpose and transparency26. Simply put, these principles require that individuals affected are informed of the purposes for which their personal data is to be collected and processed27. Any subsequent change of the purpose for which such personal data is processed is a violation of these principles and is permissible only with suitable justification28.

2.2.2.3.

Third challenge: proportionality ^

The third challenge of data protection law as it relates to e-discovery lies in the principle of proportionality which this law applies to any processing of personal data. Simply put, the principle calls for personal data to be processed only as is necessary and suitable for the use intended, and only as is reasonably acceptable for the data subjects29. In an e-discovery context this means that generally data should be disclosed only inasmuch as its disclosure is essential to the case at hand.

European data protection specialists – the aforementioned Article 29 Working Party first and foremost – have inferred from this principle of proportionality the requirement that any information to be produced in a pre-trial discovery in US proceedings must first be filtered accordingly. In its 2009 working paper, which discusses the tension between the requirements of EU data protection law versus those of US pre-trial discovery, the Working Party also comments on adherence to the principle of proportionality30. To give effect to this principle, it says, either irrelevant personal data must be removed or the existing information must be anonymised or pseudonymised. This means stripping the data of any references to individuals, for example by redacting real names or replacing them with a pseudonym31. The Working Party's rationale for this is that in and of itself, disclosure of irrelevant personal data as part of a discovery is a breach of data protection principles because by definition, processing these data is not relevant to the legal dispute. So if the identity of a given data subject (such as the sender or recipient of an e-mail message) is not relevant to the litigation at hand, then that identity must not be revealed, according to the Working Party. In this body's view the culling of irrelevant data must happen in the country of origin (before the relevant data is transferred to a third country such as the US) and is best done by a «trustworthy third party» with knowledge of, but no stake in, the litigation32.

Ultimately, what is relevant and what is not again is a matter of definition. What is relevant to the discovery is reflected above all in the parties' discovery requests and should be an outcome of the meet and confer talks or, if these fail to produce an agreement, from a corresponding court order. It is up to each party to find a way to select from its total pool of documents and data, wherever possible, only those records for discovery that belong to the subset of relevant records as defined in a previous step. Any selection errors tend to be accepted only where they favour more extensive disclosure. As a rule, then, a company need not disclose all those e-mails that meet certain formal, external criteria (such as from-to dates, recipient, sender, and/or keywords). These criteria are applied merely to begin narrowing down the selection. The company will however subject the remaining records to a semiautomatic culling process, disclosing those hits that meet certain search criteria and that in a manual review by the company's own legal counsel were not clearly recognised as irrelevant (or as exempt from disclosure for other reasons). So selecting the right keywords and the right search strategy and refining them («keyword refinement») is key in determining the subset of information for discovery. What remains by and large is what may be deemed relevant and in practice will be disclosed.

It should at this juncture be said, though, that the proportionality rule entails not only restrictions for the company concerned33. Data protection regulations do not call for every conceivable action that might be in the interest of protecting the information of data subjects. The regulations merely insist on safeguards that are reasonable. The less sensitive the data and the less adverse the data subjects' interests in their data being processed are, the less stringent are the data protection requirements for the person or entity processing their data. This rule of thumb is often forgotten.

2.2.2.4.

Fourth challenge: rights of data subjects ^

The fourth challenge concerns the guarantee of the rights of individuals who are data subjects. These rights entitle data subjects to access their personal data, to have such data rectified or erased and to object to their data being processed34. In general these rights also apply to any personal data disclosed in a discovery. Here again data protection presents a challenge not only to multinationals. Specifically, their challenge lies in that the court and the opposing party to whom the relevant personal data are to be disclosed tend not to recognise the right of individuals to access their personal data, to have it amended or deleted and to object to its processing.

2.2.2.5.

Fifth challenge: cross-border disclosure ^

The fifth challenge of data protection in a discovery context consists of restrictions on transborder disclosure of personal data. These restrictions vary somewhat country by country, even within the EU, although the basic regulatory concept is the same in every European nation, including Switzerland. According to this concept, personal data (with some exceptions) may be exported only to third countries that provide for an adequate data protection, whether by law or guaranteed through some other measure35. In the context of a discovery in a US civil proceeding, these export regulations are often considered to be of very high relevance, but they should not be overestimated. Ultimately their objective is to ensure that personal data is processed only within a tight framework even outside Europe and in countries where data protection is not the law. In Europe this framework is guaranteed by law, and transferring data collected for e-discovery purposes, between EU member states and to third countries the former recognise as safe, including Switzerland, is not a real issue. (Depending on the country, national law may impose certain additional restrictions also on exports of personal data to a «whitelisted» third country outside the EU/EEA36, which is why even in such cases consideration should be given to the national data protection law requirements in the country of export.)

The most popular approach used in transferring data internationally today is to conclude a transborder data transfer agreement. In some civil proceedings this type of agreement may be an option for a European company's communications with its US attorneys but hardly for those with the opposing party and certainly not for those with the court. This is the case in countries where in practice only the model clauses approved by the European Commission may be used. In countries where local data protection law gives data exporters more leeway in designing a measure for ensuring data protection abroad37, there may be case-specific solutions for satisfying data protection export restrictions such as protective orders containing provisions that (also) address data protection.

As a consequence, under European data protection law only two other means of legally exporting personal data are available if a flexible solution of the above sort is not an option. Either the US recipient of the data identified for discovery has self-certified compliance with the Safe Harbor Privacy Framework38 on the use of these data, thereby submitting itself to the key principles of data protection as practiced in Europe, or an exemption is invoked under European data protection law which allows personal data to be transferred if such is required for asserting, exercising or defending legal claims39. The scope of such exemption does tend to vary according to interpretation in different European countries. Occasionally it is claimed that an exemption may be invoked only in cases of international judicial assistance, which would make it seem rather redundant. More often, however, the exemption can be relied upon in the case of an e-discovery, provided certain measures are implemented to ensure that the data disclosed in the foreign proceeding is not used for other purposes, among other things40.

Against this background, the challenge for multinationals in particular lies in using the different rules in different European countries to the best of their advantage and steering clear of unfavourable export arrangements. For instance, if data from various European subsidiaries need to be collected for a US legal proceeding, the most obvious solution may be to export the data from each subsidiary directly to the US. This solution, however, is also the most complex: Although all European countries in general provide for a similar level of data protection, the formalities for exporting personal data to «unsafe» countries significantly vary among the various European jurisdictions. This can increase compliance costs, complicate matters and cause delays. Hence, it may be a better solution to first pool all e-discovery data collected in Europe in one European country, as the movement of data within Europe is normally possible without or only few or no restrictions and formalities. Once the data has been pooled in such a European country, the onward transfer of the data to the US is much easier as only one data protection regime (the one of the country from where the data is exported) has to be complied with in this regard.

2.3.1.

Case-specific and groupwide interests ^

2.3.2.

The four organisational challenges of an international e-discovery ^

2.3.2.1.

The first challenge: getting e-discovery experts on board early on ^

Ultimately, this question arises in any litigation that a multinational company finds itself drawn into in the US. Answering it is likely, at first, to baffle most individuals tasked with handling such cases41. There are two reasons for this. One, in many multinationals each such case is handled by different individuals, who then lack prior experience. Two, a consistent pattern found in many multinationals is that case handlers are neither e-discovery specialists nor familiar with specific IT (never mind the systems used in their own companies) nor with data protection legislation and other relevant legal terms of reference prevailing outside the US. Their expertise will be of a different sort: either they are in-house counsel with more or less experience in litigation and some knowledge of applicable US law, or they are particularly connected to the matter at the heart of the case and have been made the case handlers for that reason.

For one thing, many US trial lawyers – even if they are not known to admit as much – remain largely inexperienced in running e-discovery projects, and have had even less exposure to e-discovery processes extending beyond US borders. It is true that more and more big US law firms have been in-sourcing e-discovery partners or counsels, some of whom have gained extensive experience also in cross-border e-discovery projects42. In practice, however, cost considerations all too often mean that such outside expertise is not sought in every case, or not from the outset, at any rate43. For another, outside counsel typically are unfamiliar with the specific situation at the company with regard to the areas relevant to e-discovery.

Ultimately, the only means available to this end is initiating a standardized global (and centrally controlled) legal-hold process, as there seem to be no other way to ensure that data protection requirements and other international aspects are duly considered in US litigation, which, by its very nature, most times starts out with an US focus. Using a standardized process of this sort also ensures that the specialists will have sufficient time to run a standard cross border e-discovery analysis44 before the actual discovery has even begun and to change tracks if and as necessary.

Most times it is already too late to do so once the retained counsel has met and conferred with the counterparty on how to conduct the discovery45, because the basic parameters for the discovery must be in place and complied with by that stage. To this day, unfortunately, there are many outside counsel in the US who meet and confer with the counterparty before having met with their client to discuss the particular legal and organizational challenges involved in a cross-border type of e-discovery – the variety commonly facing multinationals – and to define realistic parameters. As a consequence, these challenges are not taken into account in good time. If the European special requirements are then asserted at a time when the rules for conducting the pre-trial discovery have already been agreed with the counterparty, and if the schedule is as tight as it usually is, then calls for such requirements to be met usually fall on deaf ears.

2.3.2.2.

The second challenge: educating, and working together ^

Sadly, experience suggests that the vast majority of US judges will at best be mildly sympathetic to European concerns about data protection, as they too race against the clock to work through vastly diverse cases. The subject of e-discovery in and of itself will be uncharted territory to the average US magistrate, who may face enormous challenges when expected to rule on such matters given the massive impact such rulings may have on the costs and the burden of proof required in court. That a serious knowledge gap exists in this area has now been recognized as a fact in the US46 and more and more training programs are coming on stream there to address it. Along with this, US judges tend to focus on their «home market» first, with barely any interest or resources to spare for whatever special requirements may come from abroad regarding how an e-discovery should be conducted.

Sadly, experience shows that the US Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 26 (f) dated back to December 2006 is not yet standard practice with all US attorneys. Rather than listening to the other side's concerns and working to find mutually acceptable solutions, too many are motivated by “tactical” considerations instead, resorting to excessive demands or refusing outright to cooperate47. For the clients of either side, this means incurring unnecessary and significant costs at best or, in a worst-case scenario, facing strategic disadvantages in the legal proceeding and a discovery by court order, and a subpoena if they challenge the order. In Switzerland, for example, specific legal hurdles (Art. 271 of the Swiss Penal Code) exist which may severely limit a company's options with regard to handling the documents it has stored there, and which may put the company at a serious disadvantage in the legal proceeding. Any multinational company whose plan is to avoid these scenarios therefore needs to have discussed, in advance, its own situation in terms of conducting a group-wide e-discovery case also under the technological, organizational and legal conditions prevailing outside the US. The company needs to have done this so it can educate its external US lawyers and other stakeholders on its particular circumstances and the standards it must comply with – at any time, without delay and in a documented form – and articulate the corresponding guidelines for action in an actual legal dispute. All of this preparation needs to be completed before the meet and confer begins – indeed, before an actual case even arises. Otherwise, there will not be sufficient time for the thorough kind of evaluation required, as experience has shown. This in turn means first raising awareness within the relevant units in-house to educate them on the planned course of action, given the substantial costs routinely involved even in laying such groundwork – costs that can rarely be charged directly to any specific litigation.

2.3.2.3.

The third challenge: time-consuming additional measures ^

In practice, one approach that has proven useful has the parties agree on phased discovery, starting with the – typically straightforward – US data if any. This avoids delaying the start of the discovery process while buying sufficient time for the multinational to obtain and disclose the relevant data from locations outside the US and especially from Europe48.

2.3.2.4.

The fourth challenge: compliance in practice ^

Yet another practical challenge facing multinational companies is to be meticulous enough in complying with the e-discovery requirements under US law49. It should come as no surprise then that these requirements are forever being likened to a minefield where at least one fateful misstep per case is a certain prospect for any company. And where e-discovery takes on a cross-border dimension, with a raft of additional requirements as described above, implementing the rules becomes even more challenging.

One of the difficulties routinely facing multinationals is that the processes50 developed by the industry bodies and experts – and the tools (software solutions) to implement them – often cater only to the US domestic market. Sadly, the European call for «data privacy by design» has been largely ignored by e-discovery software makers and is only gradually being addressed by their solutions.

For instance, when embarking on legal-hold and discovery processes, companies routinely find themselves having to modify the parameters software makers set for access rights to internal databases and systems. They need to modify them to allow for the required number of different roles and locations of the users involved in these processes, and to effectively restrict these users' access to only those database subsets and systems components that are essential to their ability to perform their legal-hold and/or discovery work. This includes sorting the data by their geographical origin, precisely a job that many software solutions are not yet designed to do. Some for example do not provide for «country of origin» as a meta-data category by which documents might be classified, lumping all data together instead. Where such classification is unavailable, geographical scoping – in other words, creating subsets of documents by origin – requires using a workaround. In other words, a company will be forced either to apply the strictest data-protection standards to all data indiscriminately or else accept its non-compliance with those standards, whereas scoping would enable it to apply them narrowly to relevant data.

3.1.

Introductory remarks ^

At a closer look, it becomes clear that by approaching the problem with some flexibility and an open mind set, it is in fact possible to find solutions that are workable and acceptable to all parties involved. Such solutions have also become the subject of discussions being held at the relevant international bodies, including the Sedona Conference51, and is increasingly gaining favor among those advocating full disclosure during the process as well as among data protection officials. Proposed solutions of this kind – some of which are described below – are premised on three conditions, however:

First, the party ordered to carry out a discovery inquiry in Europe must be willing in principle to disclose all relevant documents to the extent permitted under applicable law in each jurisdiction. While required or taken for granted under US procedural law, such willingness to cooperate is not a given from a European perspective. This is because the principle of total transparency as applied to a discovery runs entirely counter to the continental European legal tradition and in particular because the costs of an e-discovery, including the subsequent review of the results, are potentially staggering (In the US alone an e-discovery conducted for a major lawsuit may cost a party up to several million USD52.). Occasionally, parties to a legal action in a European country undermine the spirit of data protection law by abusing its provisions and other legislation to avert disclosure through seemingly insurmountable obstacles. In recent years, however, experience has shown that in most cases the majority of European companies will agree (albeit grudgingly) to cooperate if involved in a civil suit brought in an Anglo-Saxon jurisdiction as a result of their business activities. The same is even truer of multinationals with permanent branches in the US. There is hardly a European group or group headquarters not prepared to assist its US subsidiary in a local dispute if reasonably able to do so. Nor should the influence of legal advisors be underestimated: whenever a European company finds itself involved in some legal action in the US, it will invariably retain a legal representative for cases heard by a federal court. (In international arbitration, disclosure tends to be handled with much more restraint, although there too a trend to more expansive interpretation can be seen, driven predominantly by lawyers steeped in the US tradition.) Refusing disclosure is virtually unthinkable for US lawyers, however. Motivated by tactical considerations as much as by their native legal tradition and understanding of their role as servants of the law, they will disclose any even only loosely relevant – but not privileged – documents reviewed as part of a discovery, against their client's will if necessary, also to cover themselves.

3.2.

Understanding the company's own particular situation ^

3.2.1.

Organisational aspects particular to multinationals ^

3.2.2.

IT aspects particular to multinationals ^

Next, the company should collect information on and document where it physically stores and performs backup routines of its electronic documents and data and where the associated applications are installed, so it can establish the geographical scope and the applicable legal framework of e-discovery purposes. Special attention should be paid to cases where certain data may be stored in several countries in parallel, which may simplify their discovery considerably in the event of different legal hurdles in the relevant jurisdictions. In some cases, such information may allow the company to take precautions as appropriate. For example, it may export copies of relevant data between affiliates should blocking statutes inadvertently prevent the disclosure of such data53.

3.2.3.

How to analyse a cross-border e-discovery in a multinational firm ^

3.2.3.1.

Using internal e-discovery specialists ^

While outsourcing remains an ongoing trend in many areas, the very opposite is happening in terms of e-discovery in multinational companies: specialists and systems to handle these processes are being insourced across the board54.

Costs are just one factor driving this. More and more companies of a certain size and global reach that have latent exposure to litigation risk in the US are building e-discovery know-how and infrastructure in-house for further reasons: they will become more efficient and effective at working through the challenges involved in cross-border e-discovery projects, but also to mitigate risks in the international arena. This appears to be the motivation especially of a growing number of multinationals headquartered in Europe, whose targeted development of e-discovery specialists in-house is meant to move the process under better central control and, with that, ensure that it factors in the international dimensions to an e-discovery more regularly and, above all, from an early stage55. Accordingly, e-discovery units can be found in European as well as US-based multinationals, and in many of the former they are even run by Europeans.

Creating an internal e-discovery organisation and staffing it with the requisite specialists is an indispensable step also toward centralising and standardising group-wide the legal-hold and e-discovery processes as such56, which conforms with the spirit of both European data protection statutes and, ultimately, US procedural law.

3.2.3.2.

Using internal e-discovery systems ^

More and more multinationals are using workflow-based legal-hold systems57. This is because such systems not only help to make a legal hold more efficient and more defensible to perform, they also offer substantial advantages to companies as they prepare to disclose documents in a cross-border e-discovery. Depending on the used system it may permit to either directly preserve or collect data or at least send out preservation or collection plans centrally. Both ways will serve a critical requirement, that all actions performed per legal case are documented in a central place in line with applicable legal requirements. In addition, via such systems it is much easier to keep track of scope changes in respect of employees, data sources and timeframes involved. Keeping track of scope changes such as releasing custodians or data identified as not relevant during the discovery process is necessary from a data protection standpoint but pretty burdensome and less defensible if not handled via a system logging such steps appropiately.

Similarly, beyond preserving electronic correspondence for legal and business purposes, e-mail archiving systems – if offering the necessary functionalities – can be used for legal hold and e-discovery purposes as well. The IT and the legal department should work closely together to be able to define the full set of requirements for all relevant countries. Experience has shown58 that the core strength of most of those systems is still to fulfill the IT storage requirements in case this is the vendor's core domain. The e-discovery solutions seemed to be «add-on solutions» which failed to provide European data protection requirements as purely developed with an US focus. For example, the ability to only grant access to e-discovery personal to the relevant proportion of the data e.g. scoped by country or at least custodian and time period at issue, has not been possible in the standard offering. The transparency requirement to grant employees access to «their» e-mails when it comes to the journaling of e-mails for preservation purposes has also not been foreseen. One solution to overcome such short comings may be to combine an archive with a search product. Such combinations can be ideal both for preservation and early case management activities. Via the preserve-in-place option e-mails may be put on a legal hold on a case-by-case basis without any additional data transfer. In addition, it offers cost benefits while allowing for centralised and transparent monitoring of a legal hold's implementation. At the same time, such systems can be used to tag positive data by geographical relevance prior to data sharing and discovery.

3.3.1.

Preliminary remarks ^

3.3.2.

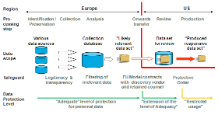

Standard procedure for conducting e-discovery in Europe ^

In response to these conditions a standard procedure evolved in recent years for e-discovery exercises in Europe, a procedure that has come to be widely used by multinationals in their efforts to comply with the requirements of both jurisdictions wherever possible59. Various versions of the procedure have been described in the literature and discussed in specialist bodies. The recently published «International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection» by The Sedona Conference Working Group 6 also contains a «Cross-Border Data Safeguarding Process + Transfer Protocol»60, which reflects most of the thoughts below.

This procedure has proved to work surprisingly smoothly in practice. No incidents contravening data protection laws or significant interventions by data protection agencies have been reported. The procedure was even discussed with and welcomed by the Article 29 Data Protection Working Party even though it does not meet the standards set (or at least communicated originally61) by this body and merely represents a (useful) compromise. Quite likely, however, it is this very approach – preferring usability over perfection – that accounts for the procedure's success.

A first stage involves the targeted collection of forensically accurate copies of data pre-identified in every European subsidiary where relevant data may be stored, which is transparent to the affected employees. Following the written legal hold notice, the employees are given a questionnaire asking them to identify the data sources on which they have been storing any documents and information potentially relevant to the case at hand62. The questionnaire should prompt them to be as specific as possible and as expansive as necessary in answering the questions. This will ensure from the outset that no unreasonable amount of irrelevant data is collected later on. In addition, the employees should indicate whether in the identified targeted areas sensitive personal data or private data may be stored. In terms of the company systems familiar to them, the employees should be asked to be as precise as possible in identifying the area and type of personal data that is potentially relevant according to the scope instructions provided. For instance, they should indicate the folders they have been using for storing files on their local hard drives and network drives, if any, to avoid having entire computers or servers subject to the discovery, which tends to be the default procedure. Crucially, the employees should be given clear and detailed instructions on this point and their responses must be verified and followed up on, to avoid collecting data too narrow in scope and thus risking non-disclosure. If the legal-hold notice did not inform the employees of the need or obligation of their multinational to compile certain data as a precaution or for review in an actual dispute, this survey will close this gap and will do so before such data are collected. The reasons for collecting the data need to be explained by identifying clearly the legal proceeding for which the data will be needed to be preserved, processed, transferred and ultimately produced in the US or other venue at hand.

At a second stage the data collected in the European subsidiaries is often compiled in a central location in Europe using a proprietary database of the multinational or a so-called early case assessment database supplied by an e-discovery service provider; transferring the data within Europe is usually a straightforward matter in terms of data protection laws63. If the company in question already has an early case assessment suitable solution in place based on an archiving solution (see Chapter 3.2.3.2 above) it may not be required to collect the data separately for the discovery purposes. To qualify, however, this solution would need to have been factory-designed to double as an early case assessment database for discovery purposes, with built-in security and data protection suitable features, filters and export interfaces. Inevitably, such archives will include large quantities of irrelevant information and possibly private data as well. Whether using a proprietary system or an archiving solution, the company must ensure that no data in scope can be deleted, modified or lost in non-compliance with the preservation obligation. (If using an archiving solution in parallel, the company must ensure in particular that the feature that automatically deletes data upon the end of their defined archiving period – frequently the default setting – is turned off for the affected data in scope, so that documents for relevant custodians are continued to be preserved for the duration of the legal hold). Access rights to the secured data should be restricted to a small group of individuals who have been trained for this purpose and are authorized on a case-by-case basis. For tracking and audit purposes, any operation performed on the database should be logged automatically as a single event and made retrievable through ad-hoc reports.

Where disclosure is initiated as part of a pre-trial discovery, a third stage involves culling the information gathered once or multiple times, semi-automatically, usually in the early case assessment database, to identify irrelevant documents and remove them physically or at least logically64. The data culling is performed manually, whereby e-discovery experts work with individuals familiar with the case to define culling and search parameters and to test and, where necessary, refine these down – for example, by entering key words, dates, file folders, document names, or sender and recipient names. This is done for the purpose of identifying and exporting all of those documents that are likely relevant excluding documents clearly irrelevant, to the case at hand, without having to view every single document. A tried-and-tested method for efficiently refining keywords is using identified terms by either excluding groups of false positives (separating them with the «NOT» operator) or by grouping keywords (operator «AND»)65. For obvious reasons, searches are often started with broad keywords, such as general descriptive terms, first or last names and case-specific abbreviations. Often, suppressing documents that otherwise will come up in search results even though they are in fact irrelevant – so-called false positives – requires working through numerous variations of different keyword and operator combinations, linked and non-linked, before an effective combination of search terms is found for extracting the documents identified for disclosure. This approach helps protect data privacy but also helps cut costs – the lower the data volume, the lower the costs of reviewing them. As a result, the process of culling is known and accepted in the US as well66. The parties, however, should agree this approach in writing during the meet and confer, including the culling criteria respectively search term refinement applied (hence the importance of running relevant searches, and preparing proposals based on the search results, ahead of such meeting). Specialists are being assisted by ever more powerful search and filter tools marketed these days by the makers of various e-discovery programs. However, the use cases and limits on how to use predictive coding software are discussed controversially following the 2012 Da Silva Moore case opinion67.

In the interest of data protection, initial culling should happen while the data are still in Europe, in the early case assessment database itself. The outcome will be a noticeably slimmer database of «likely relevant data». These data will not have been redacted or manually sorted, however. The only time a thorough manual review is usually conducted before the early case assessment database or the documents being saved to it are exported is when the mere act of exporting the data may result in criminal sanctions. As mentioned, this is sometimes the case in certain European countries with regard to specific types of business secrets, for example.

At a fourth stage the «likely relevant» data that has been collected and pre-culled is usually sent to the multinational's own lawyers in the US or is made available to these by remote access to the review system of an e-discovery provider in the US or in Europe68. Data protection specialists see the latter option – remote access – combined with keeping the data in Europe as interfering less with the privacy rights of any individuals affected. Providing remote access is preferable therefore to sending a full copy of the likely relevant data to the US. Yet, experience shows that with remote access to a database hosted in Europe, costs are up to 25% higher than if a US-based e-discovery provider is used. At the same time, these authors do not consider the European option, with remote access from the US, to be essential in case additional appropriate safeguards have to be in place, including for non data protection reasons such as protection against the risk of a forced disclosure by US authorities (which is usually less than the risk of an issue in a civil matter, but may be relevant in cases of governmental investigations). Also, granting remote access out of Europe to US attorneys located in the US may still be less costly than flying-in US lawyers to review documents on-site in Europe, which would be unreasonable to do purely for the sake of data protection (but may be warranted for other reasons such as statutory secrecy requirements that prohibit the export of certain documents). That said, we note that the costs of conducting reviews in Europe have meanwhile come down significantly; depending on the circumstances such as the languages at issue, the quality and efficiency of work may be higher when using local reviewers that are more familiar with the languages, the local environment and the local habits.

At a fifth and final stage the data manually reviewed and (where necessary) redacted during the fourth stage are disclosed by the US-based lawyers to the counterparty. In this process, the data leave the domain of the disclosing party. Still, safeguards can and should be put in place to ensure that the data is under some measure of protection even after it has been disclosed69.

3.4.1.

Preliminary remark ^

3.4.2.

Crossborder disclosure ^

In the first instance, this concerns the challenge posed by data protection requirements for crossborder disclosure of personal data. Without disclosure across national borders, e-discovery is impossible in Europe. At the same time, the legal scope for such disclosure is limited, as discussed above70. This must be seen in terms of each of the various stages involved in the procedure. If the above e-discovery standard procedure is adopted, transborder disclosure of personal data begins with the consolidation of data within Europe. Typically, however, such consolidation is not subject to any restrictions under data protection law that add to costs or complexity, as the data transfers involved are within the EEA single market or else to a «safe» or «whitelisted» third country such as Switzerland.

There is a need for targeted action only when a company sets out to transfer its consolidated e-discovery data to the US, given that the US is not classified as a whitelisted third country from a European point of view. In most cases, an obvious way to still comply with applicable minimum data protection standards will be to enter into a formal agreement including the model clauses issued by the European Commission (EU model clauses). In practice this may well be the most popular method of safeguarding data that are going to be transferred to the US. Even so, experience shows that it may be worthwhile looking into other methods, and evaluating a range of possible scenarios even when using the EU model clauses. Multinationals in particular will do well to do so if they own subsidiaries in a number of countries including, in some cases, in the US. It will give them a broader range options with regard to possible exporters and importers of data: For example, it may be more straightforward and more efficient for a multinational first to transfer the data it has pooled from its European subsidiaries to a US parent or subsidiary affected and only then to make the data available to the attorneys in the US, rather than sending these attorneys the data in separate transfers from each subsidiary directly. This will be advisable for example where a suitable data transfer agreement with the US subsidiary is already in place or sufficient binding corporate rules exist within the multinational71, or if the US subsidiary is Safe Harbour certified for the type of data in question72. In any case, the multinational will need to verify that applicable data protection regulations permit disclosing the data in a legal proceeding as well as transferring them to the company's own legal counsel. In real life this aspect is often ignored or left out, such as when the EU standard contractual clauses are used. The most popular standard clauses for data transfers between data controllers are the ones dated December 200473. Pursuant to para. II(i) of these clauses, the transfer of personal data by data importers located outside the EEA, for example, is permitted only on certain conditions. Accordingly, such transfer may only be made to a safe third country (which excludes the US for companies without adequate Safe Harbour certification), or if the data importer becomes a signatory to the clauses (which an opposing party or the court in the US is unlikely to do), or if the data subjects have been given the opportunity to object once informed of the purposes of the transfer (which may be feasible in dealing with the company's own employees but with any other data subjects it certainly is not). Hence, if personal data is transferred to the US for discovery purposes, on the basis of these standard clauses, the discovery will invariably lead to a breach of contract. So if the data exporter is able to anticipate a breach he should not export the data, strictly speaking, even though he would be doing so having agreed the standard clauses. The EU standard clauses for transfers of personal data to processors, of February 201074, are less restrictive on this point but may create different complications case-by-case because of certain additional requirements such transfers must meet in some EU member states75. There is far more leeway in cases where data transfers can be carried out with Safe Harbour certification. Certified companies are largely free, within the bounds of their data protection guidelines and the certification rules, to decide how to ensure adequate protection for any data they transfer onward. (Admittedly the onward transfer of personal data for discovery in a civil proceeding is rarely a consideration when firms define their data protection guidelines.) Meanwhile several notable US law firms and e-discovery service providers have become compliant with the Safe Harbour Privacy Framework through self-certification, which can be very helpful when data need to be transferred to these firms from an EEA country or Switzerland.

Consolidating European data for discovery purposes in one European country can streamline such a discovery significantly, as the rules of only one country have to be followed with regard to the envisaged data export into the unsafe country. The United Kingdom is one of the countries used for such purposes; Switzerland is another case in point: While Switzerland provides for the same level of data protection as all EU countries do, Swiss data protection law is much less formalistic as to the question how a particular level of data protection is achieved, as long as it is achieved. For instance, Switzerland does not prescribe any formal requirements, in law or in custom, as to how a contractual guarantee for ensuring an adequate level of data protection in an unsafe third country has to be worded, as long as the guarantee is adequate76. The EU standard clauses are recognised in Switzerland, as well. But a data exporter from Switzerland is free to make any alternative provisions (including ones rather shorter and simpler or occasionally more tailored to the case at hand) if these provisions serve to guarantee an adequate level of data protection on the data importer's side abroad77. Also, Switzerland's status as a safe third country78 means that data collected in the EU for e-discovery purposes is usually easy to export to Switzerland. Once the data have been consolidated in Switzerland, their exportation is subject only to Swiss data protection law which, as discussed above, is less formalistic than the corresponding laws of certain other EU countries. This may be of key importance in the case of a legal proceeding where an opposing party will usually not be willing to enter into the EU standard clauses, but may be receptive for using alternative instruments such as protective orders adapted to provide for the necessary degree of data protection79. Such pragmatic solutions are possible under Swiss law. This is not to say that solutions like these necessarily come without challenges of their own. Switzerland does offer a far more flexible and, therefore, a more attractive regulatory environment than most of the EU when it comes to data protection. By the same token, the Swiss legal system is far more protective of its jurisdiction against the reach of foreign governments than are many of its peers. In and of itself, this is no hindrance to a company's voluntary participation in a pre-trial discovery. But the same disclosure is a punishable offence if made by US court order80. The above examples and discussions illustrate that the challenge involved in complying with data protection rules in a crossborder discovery is not whether compliance is possible but how best to go about it. In this regard, the very channels of communication often available to multinationals may prove an asset, as resolving the legal aspects of this challenge may require first routing the data streams accordingly.

3.4.3.

Protecting the data post-discovery ^

The standard procedure entails the issuance of a protective order by the US court with jurisdiction on the case. As a rule, this order is drafted and negotiated by the parties jointly and is issued by the court, and covers any personal data disclosed in discovery. Protective orders are widely used in US civil proceedings but mainly to protect business secrets from disclosure by the opposing party and other persons involved in the legal proceeding, such as witnesses or experts. At the same time, a protective order ensures that the court will not make these records available to the public (as is customary with parties' submissions and documentary evidence filed in US civil proceedings81) but will keep them under seal instead.

Because protective orders and confidentiality agreements are legal instruments known to and accepted by every US attorney and every US court, they have proved ideally suited in recent years to enforcing protection of personal data disclosed pre-trial or during a legal proceeding. To such end, all personal data (as defined under EU law) are governed by the same protections as are companies' trade secrets82, on the one hand, while the recipients of such secrets on the other hand are not only bound by secrecy but are also prohibited from using the data for any purposes not directly related to the legal proceeding, to the extent that these recipients are not prohibited from doing so already. If the records are made available to third parties, it must be ensured that these parties too are subject to the restrictions of the protective order (or that a confidentiality agreement is in force which prohibits disclosure to third parties or limits such disclosure to certain defined conditions). As a rule, protective orders also stipulate that the records must be destroyed or returned after the legal proceeding has ended or after use.

4.

Summary ^

5.

Literature ^

Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, Working Document 1/2009 on pre-trial discovery for cross-border civil litigation, adopted on February 11, 2009.

Hill, Brian W., Owens, Leslie, Searching For eDiscovery Cost Control, Forrester Research, Inc., April 27, 2009.

Kaplan, Ari, Advice from Counsel: Best Practices on Controlling E-Discovery Costs, FTI Consulting, 2009.

Kravitz, Mark R, Memo from Honorable Mark R Kravitz, Chair, Advisory Committee on Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to Honorable Lee H. Rosenthal, Chair, Standing Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure RE: Report of the Civil Rules Advisory Committee (May 17, 2010).

Logan, Debra, Andrews, Whit, Bace, John, MarketScope for E-Discovery Software Product Vendors, Gartner Report, December 21, 2009.

NIST, US Department of Commerce, Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), Special Publication 800–122.

Rosenthal, David, E-discovery in Switzerland: How to deal with DP restrictions, in: Privacy Laws & Business International, October 2007, pp. 9 et seq.

Rosenthal, David, Jöhri Yvonne, Handkommentar zum Datenschutzgesetz, Zürich 2008.

The Sedona Conference Working Group 6, Comment of The Sedona Conference Working Group 6 to Article 29 Data Protection Working Party Working Document 1/2009 («WP 158»), October 30, 2009.

The Sedona Conference Working Group 6, The Sedona Conference International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection, European Union Edition, Public Comment Version, December 2011.

The Sedona Conference, The Sedona Conference Cooperation Proclamation, The Sedona Conference Journal, Volume 10 Supplement, Fall 2009.

The Sedona Conference, Commentary on Achieving Quality in the E-Discovery Process, May 2009.

Tero,Vivian, Corporate eDiscovery Technology Trends 2009: Doing More with Less While Facing Increasing Complexity in eDiscovery, IDC Information and Data sponsored by FTI Technology, November 2009.

Zeunert, Christian, Kos, Patrick, Daley, James, Rosenthal, David (The Sedona Conference), Working Through the Maze, Part 2: Cross-border Discovery Preparedness & Protocols, 2nd Annual Sedona Conference International Programme on Cross-Border Discovery and Data Privacy, September 15–16, 2010, Washington D.C., USA.

This article is an (updated) translation of a German contribution that first appeared in the German book «Internationale E-Discovery und Information Governance», edited by Prof. Dr. Matthias H. Hartmann, and published by Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin, Germany, in 2011 (the German version is freely available from the authors upon request). Christian Zeunert can be reached at Christian_Zeunert@swissre.com and David Rosenthal at david.rosenthal@homburger.ch.

David Rosenthal, Homburger, Zürich, Switzerland

David Rosenthal is counsel and co-head of the IT practice at Homburger, one of the leading Swiss business law firms. He is active in IT and other technology transactions, disputes and regulatory matters as well as in white collar investigations and e-discovery matters. He has published a leading commentary on Swiss data protection law, authored many articles and is a frequent speaker on the topic. He also lectures at the University of Basel Law School and the Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich.

Christian Zeunert, Swiss Reinsurance Company, Zurich, Switzerland

Christian Zeunert is Head E-Discovery Management at Swiss Re, one of the world's leading reinsurers, based in Zurich, Switzerland. He is responsible for developing, implementing and enforcing Swiss Re's e-discovery strategy and reports to the Claims and legal division. He is a steering board member of The Sedona Conference® Working Group 6 and member of the drafting team of their International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection. Mr. Zeunert is also co-author of a section of the first German speaking book on e-Discovery as well as frequent speaker of e-Discovery conferences.

- 1 These are the lists of those categories of documents (including ESI) which each party demands from the other as a part of a voluntary pre-trial discovery of documents and information.

- 2 One of the toughest sanctions is known as adverse inference, whereby the jury is instructed to presume the documents lost or not disclosed to be unfavourable to the cause of the party which failed to discover or preserve them, in other words, to presume that such documents would corroborate the other party's claims. Among the best-known cases to involve such sanctions is The Pension Committee of the University of Montreal Pension Plan, et al. v. Banc of America Securities, LLC, No. 05 Civ. 9016 (SAS), 2010 WL 184312 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 15, 2010), in which several of the plaintiffs had failed to preserve possibly relevant documents at the time the suit was filed.

- 3 An independent European advisory body on matters relating to data protection, established under Art. 29 of EU Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC.

- 4 Article 29 Data Protection Working Party, Working Document 1/2009 on pre-trial discovery for cross-border civil litigation, adopted on February 11, 2009, also known as WP 158 (ref. «WP158»), http://ec.europa.eu/justice/policies/privacy/docs/wpdocs/2009/wp158_en.pdf.

- 5 The Sedona Conference Working Group 6, Comment of The Sedona Conference Working Group 6 to Article 29 Data Protection Working Party Working Document 1/2009 («WP 158»), October 30, 2009.

- 6 See footnote 1.

- 7 US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 26(f).

- 8 This refers to the preservation of records as performed in the normal course of business (i.e., conventional records management), in other words before companies are targets of legal action and before their records management is subject to special requirements in connection with the legal action.

- 9 Restatement (Third) of Foreign Relations Law of the United States, no. 442.

- 10 Cf. Société Nationale Industrielle Aérospatiale v United States District Court, 482 U.S. 522, 544 n.28 (1987); Volkswagen AG v Valdez, No. 95-0514, 16 November 1995, Texas Supreme Court; In re: Baycol Products Litigation MDL no. 1431, 21 March 2003.

- 11 See e.g. Art. 271 of the Swiss Penal Code and French Penal Code Law No. 80–538.

- 12 Not to be confused with procedural orders such as scheduling orders which merely set the timetable for proceedings and thus also define the timing of the parties' discoveries, such disclosures being voluntary rather than compulsory (as when ordered subpoena) under this type of instruction; for a full discussion, see Rosenthal, Handkommentar zum Datenschutzgesetz, Zurich 2008 (in German), Art. 271 StGB, N 19 et seq.

- 13 Art. 271 of the Swiss Penal Code, which stipulates a penalty of three years' imprisonment or a fine for the individuals in charge.

- 14 Including Spain, France and the Netherlands.

- 15 As in Swiss law, for example, which in the context of international mutual legal assistance even allows for depositions through a commissioner. In Switzerland, international mutual legal assistance is exempted also from data protection legislation (Art. 2(2)(c) of the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection).

- 16 Which historically has depended largely on how well the parties cooperate, and how well such requests are researched and prepared, on a case-by-case basis.

- 17 Examples of such secrecy include professional secrecy (as in Swiss banking secrecy which strictly prohibits disclosing banking client data to entities abroad as there Swiss banking secrecy cannot be guaranteed; another example is Germany's secrecy of telecommunications which is sometimes interpreted to extend even to employees' e-mails stored on their employer's own servers) and contractual secrecy defined so as not to be restricted by civil proceedings and to not allow disclosure even if the parties to the proceedings themselves are bound by secrecy. Whether or not such a clause applies will be a matter of legal interpretation as such rules are rarely drafted with the possibility of a discovery in court proceedings (let alone proceedings abroad) in mind.

- 18 Such as in Art. 273 of the Swiss Penal Code or in Art. 124 of the Austrian Penal Code.

- 19 Such as redacting certain parts of the text or requesting protective orders.

- 20 In the UK the Information Commissioner has the authority to issue fines of up to GBP 500 000 while in Spain fines may be as high as EUR 600 000. In France meanwhile the maximum fine was raised to EUR 150 000 several years ago. In Germany violators may be fined up to EUR 300 000 and in some cases may even face imprisonment.

- 21 Art. 139 of the Swiss Federal Law on International Private Law (IPRG); see Rosenthal, footnote FN 12, Art. 139 IPRG, N 2.

- 22 Art. 2 of Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of October 24, 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and the free movement of such data («EU Data Protection Directive»).

- 23 Including in Canada, whose Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act establishes that information relating to the name, title, work address and telephone number of an organisation's employee shall not be deemed personal data.

- 24 Including in Switzerland, Italy, Austria, Luxembourg and Denmark, among others.

- 25 Cf. for example NIST, US Department of Commerce, Guide to Protecting the Confidentiality of Personally Identifiable Information (PII), Special Publication 800-122, p. 2-1 (http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/nistpubs/800-122/sp800-122.pdf).

- 26 The Sedona Conference Working Group 6, The Sedona Conference International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection, European Union Edition, Public Comment Version, December 2011: Principle 5, Comment 6.

- 27 Art. 6 and 10 of the EU Data Protection Directive; Art. 4(3) and 4(4) of the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection.

- 28 Art. 7, 11 and 13 of the EU Data Protection Directive; Art. 12(1) and 12(2) and Art. 13 of the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection.

- 29 Art. 6 of the EU Data Protection Directive; Art. 4(2) of the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection.

- 30 WP158, footnote 4.

- 31 WP158, footnote 4, p. 12.

- 32 WP158, footnote 4, p. 12 ff.

- 33 The Sedona Conference Working Group 6, The Sedona Conference International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection, European Union Edition, Public Comment Version, December 2011: Principle 2.

- 34 Art. 12 and 14 of the EU Data Protection Directive; Art. 5, 8, 12(2)(b) and 15 of the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection.

- 35 Art. 25 et seq. of the EU Data Protection Directive; Art. 6 of the Swiss Federal Act on Data Protection.

- 36 These requirements concern export notification to or export permits from the data protection agencies having jurisdiction in the exporting country (including Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, Iceland, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Romania and Spain, among others).

- 37 Such as in Switzerland, where Art. 6(2)(a) of the Federal Act on Data Protection allows companies to conclude any agreements, but also to use other means, to guarantee adequate levels of data protection abroad.

- 38 See http://www.export.gov/safeharbor.

- 39 Art. 26(1)(d) of the EU Data Protection Directive.

- 40 See Chapter 3.4.3 below.

- 41 Employees entrusted with managing litigation are referred to as case handlers throughout the remainder of this document.

- 42 Among them many members of the Sedona Conference Working Group 6.

- 43 At least some companies have started routinely consulting their national e-discovery counsel whenever facing new litigation in the US.

- 44 See Chapter 3.2.3.1 below

- 45 US Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 26f. Under the rule, the parties to litigation must, in good faith, confer on any obstacles and issues as may exist in connection with a discovery and resolve these wherever possible, before the formal stage of the discovery begins. The parties should jointly arrive at a plan defining the scope, sequence and form of the disclosure of documents for the purposes of the discovery.

- 46 See e.g. the memo from Honourable Mark R Kravitz, Chair, Advisory Committee on Federal Rules of Civil Procedure to Honourable Lee H. Rosenthal, Chair, Standing Committee on Rules of Practice and Procedure RE: Report of the Civil Rules Advisory Committee (May 17, 2010).

- 47 See also The Sedona Conference, The Sedona Conference Cooperation Proclamation, The Sedona Conference Journal, Volume 10 Supplement, Fall 2009.

- 48 See Chapter 3.3.2 below.

- 49 As illustrated e.g. in the various publications of the Sedona Conference Working Group 1.

- 50 Probably the best-known standard used to define the e-discovery process in the US is the Electronic Discovery Reference Model (EDRM), as detailed at http://edrm.net. See, by contrast, the standard cross border e-discovery procedure followed in Europe (see 3.3.2 below).

- 51 Annual Sedona Conference International Program on Cross-Border Discovery and Data Privacy.

- 52 Costs will vary case-by-case and in particular according to the data volume (volume times fees) but also depending on the efficiency of the processes used (such as reducing data volumes before reviewing the data manually).

- 53 See Chapter 2.2.1 above.

- 54 Cf. e.g. Hill/Owens, Searching For eDiscovery Cost Control, Forrester Research, Inc., April 27, 2009; Tero, Corporate eDiscovery Technology Trends 2009: Doing More with Less While Facing Increasing Complexity in eDiscovery, IDC Information and Data sponsored by FTI Technology, November 2009; and Kaplan, Advice from Counsel: Best Practices on Controlling E-Discovery Costs, FTI Consulting, 2009.

- 55 See Chapter 2.3.2 above.

- 56 See Chapter 3.3.2 below.

- 57 Logan/Andrews/Bace, MarketScope for E-Discovery Software Product Vendors, Gartner Report, December 21, 2009

- 58 Evaluation performed on systems available in Q1 2011.

- 59 While no statistics are available, these statements are supported by information shared among multinationals in relevant industry bodies on e-discovery on the one hand and on the other by empirical evidence from corporate law firms practising in this area in various European countries and in the US.

- 60 See The Sedona Conference Working Group 6, The Sedona Conference International Principles on Discovery, Disclosure & Data Protection, European Union Edition, Public Comment Version, December 2011, Appendix C.

- 61 WP158, footnote 4.

- 62 An efficient way to do this is using specialised software that supports legal-hold workflows. Alternatively, employees may be queried following a conventional interviewing process.

- 63 There are exceptions to this rule as well, such as France's data protection legislation which severely restricts the conditions under which employees' personal information may be exported.