1.

Introduction: What ^

As regards style, most contracts resemble laws, with all their dense text, paragraphs, and internal references. They are structured in a peculiar way and use language that non-experts often find overly complicated and hard to understand. Contract drafters tend to copy-paste clauses and prefer «tested language» in widely used clauses. Such language is presumed to have a clearly established and «settled» meaning. The result is often a writing style that has, according to one critic, four outstanding characteristics. It is «(1) wordy, (2) unclear, (3) pompous, and (4) dull».3 «Tested language» and «settled» meanings are in fact language that has been the subject of litigation. Which raises the question: why rely on language that resulted in litigation? While such language may help to win a battle in court, it does not help those who want to avoid such conflict.

As regards content, current contracts tend to focus on worst case scenarios rather than on how the parties will work together to secure business success. Year after year, limitations of liabilities and indemnities top the list of most frequently negotiated contract terms.4 While the terms dealing with consequences of failure, claims, and disputes are important, contract drafters should not overlook the fact that a large part of contracts – and the information needs of everyday contract users – are about business and financial terms, such as statements of work, specifications, and service levels.5

2.

Clients Need (and Deserve) Better, Readable Contracts ^

In order for contracts to work effectively as both business tools and legal tools, they need to communicate information effectively to both business and legal audiences. So far, the focus of contract drafters has been predominantly on the needs of the latter. Generations of law teachers have equated contracts with contract litigation, the subject of their courses.6 Most of the discussion about using contracts has been about applying them in court, reactively, ex post, after a dispute has arisen. Business people – clients – as users and readers of contracts have been neglected to a great extent. Contract readability is seldom even discussed. If it is, this happens in the context of ambiguity, vagueness, loopholes and other legal problems encountered when interpreting contracts in court or in the shadow of a dispute. While these discussions remain important, readability in clients’ commercial contexts is a different issue.7

3.

Readability through Information Design and Visualization ^

4.

Examples of Using Information Design and Visualization in Contracts ^

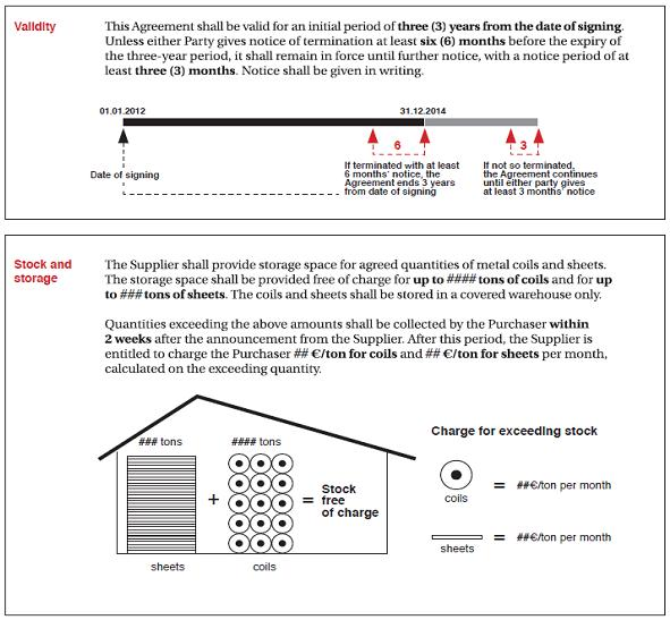

Figure 1: Examples of visualized clauses in a Framework Agreement: validity (top) and storage conditions (bottom). (© 2012. Aalto University / Stefania Passera. Used with permission.)

In these examples, the text of the contract has remained the same. Here, visuals are not intended to substitute text; they are used to clarify it. The sample contract prototype produced using information design and visualization in this case study incorporates

- document design principles that make them easier to read and to use

- images and summaries that show the big picture framework

- icons and graphics that provide an overview and emphasize key points

- visual cues that provide prominence to certain pieces of information

- a layout and colors that engage readers and help them navigate the materials

In addition to the obvious benefits this merger can bring to clients, it offers benefits to lawyers as well. For instance, a visualization of the scope, delivery limits, or technical aspects of a product or system can help lawyers elicit information about and understand the core issues involved. Process maps and swim lanes can be used to visualize business processes that involve more than one department (for example, customer, sales, contracts, legal, and fulfillment) to clarify the sequence of events, how information or material passes between sub-processes, and how various parties’ actions depend on one another. Swim lanes can also be used to illustrate the steps and who is responsible for each one, as well as how delays and mistakes are most likely to occur.28 Timelines can be used to clarify contract duration and help the parties articulate tacit assumptions and clarify and align expectations.29 And the list goes on.

5.

Conclusion ^

6.

References ^

Albers, Michael J., Information Salience and Interpreting Information. In: SIGDOC ‘07 Proceedings of the 25th annual ACM international conference on Design of communication, 22–24 October, El Paso, Texas. ACM, New York, NY, pp. 80–86. (2007).

Barton, Thomas D., Collaborative Contracting as Preventive/Proactive Law. In: Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde & Østergaard, Kim (eds.), Proactive Law in a Business Environment. DJOF Publishing, Copenhagen, pp. 107–127 (2012).

Cummins, Tim, Contracting as a Strategic Competence. International Association for Contract and Commercial Management IACCM. http://www.iaccm.com/library/nonphp/contracting.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012 (2003).

DiMatteo, Larry, Siedel, George & Haapio, Helena, Strategic Contracting: Examining the Business-Legal Interface. In: Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde & Østergaard, Kim (eds.), Proactive Law in a Business Environment. DJOF Publishing, Copenhagen, pp. 59–106 (2012).

Etzkorn, Irene A., Ten Commandments of Simplification. http://centerforplainlanguage.org/about-plain-language/ten-commandments-of-simplification/ last accessed 24.12.2012 (n.d.).

Evans, Martin, Criteria for Clear Documents: a Survey. Technical paper 8. Simplification Centre, University of Reading. http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC8CriteriaSurvey.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012 (2011).

Haapio, Helena, A Proactive Approach to Law. In: Schweighofer, Erich, Geist, Anton & Staufer, Ines (eds.), Globale Sicherhet und proaktiver Staat – Die Rolle der Rechtsinformatik. Tagungsband des 13. Internationalen Rechtsinfromatik Symposions IRIS 2010. 2nd edition. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft, Wien, pp. 625–628 (2010).

Haapio, Helena, A Visual Approach to Commercial Contracts. In: Schweighofer, Erich & Kummer, Franz (eds.), Europäische Projektkultur als Beitrag zur Rationalisierung des Rechts. Tagungsband des 14. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik Symposions IRIS 2011. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft, Wien, pp. 559–566 (2011).

Haapio, Helena, Making Contracts Work for Clients: towards Greater Clarity and Usability. In: Schweighofer, Erich, Kummer, Franz & Hötzendorfer, Walter (eds.), Transformation juristischer Sprachen.Tagungsband des 15. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik Symposions IRIS 2012. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft, Wien, pp. 389–396 (2012).

Haapio, Helena, Contract Pictures: A Means to Prevent Misunderstandings and Unnecessary Disputes. Paper accepted for presentation at the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2013, Salzburg, Austria 21–23 February 2013. (2013).

Haapio, Helena & Siedel, George, A Short Guide to Contract Risk. Gower Publishing, Farnham (2013).

Hayhoe, George F., Telling the Future of Information Design. Communication Design Quarterly Review, Vol. 1, Issue 1, Fall. http://sigdoc.acm.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/CDQR_1-1_Fall2012.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012 (2012)

Hetrick, Patrick K., Drafting Common Interest Community Documents: Minimalism in an Era of Micromanagement. Campbell Law Review, Vol. 30, Issue 3, Spring, pp. 409–435. http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1472&context=clr last accessed 11.12.2012 (2008).

IACCM, 2011 Top Terms in Negotiation. International Association for Contract and Commercial Management IACCM. https://www.iaccm.com/members/library/files/top_terms_2011_1.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012 (2011).

Kimble, Joseph, Lifting the Fog of Legalese. Carolina Academic Press, Durham, NC (2006).

Kimble, Joseph, Writing for Dollars, Writing to Please. The Case for Plain Language in Business, Government, and Law. Carolina Academic Press, Durham, NC (2012).

Macneil, Ian R. & Gudel, Paul J., Contracts – Exchange Transactions and Relations. Cases and Materials. 3rd edition. Foundation Press, New York, NY (2001).

Malhotra, Deepak, Great Deal, Terrible Contract: The Case for Negotiator Involvement in the Contracting Phase. In: Goldman, Barry M. & Shapiro, Debra. L. (eds.), The Psychology of Negotiations in the 21st Century Workplace. New Challenges and New Solutions. Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 363–398 (2012).

Mellinkoff, David, The Language of the Law. Little, Brown & Co., Boston, MA (1963).

Passera, Stefania, Enhancing Contract Usability and User Experience through Visualization – An Experimental Evaluation. In: Banissi, Ebad et al. (eds.), 16th International Conference on Information Visualisation, IV2012, 11–13 July 2012, Montpellier, France. IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos, CA, pp. 376–382 (2012).

Passera, Stefania & Haapio, Helena, The Quest for Clarity – How Visualization Improves the Usability and User Experience of Contracts. Manuscript submitted for publication in Huang, Maolin & Huang, Weidong (eds.), Innovative Approaches of Data Visualization and Visual Analytics (DVVA 2013). IGI Global (forthcoming)

Pohjonen, Soile & Visuri, Kerttuli, Proactive Approach in Project Management and Contracting. In: Haapio, Helena (ed.), A Proactive Approach to Contracting and Law. International Association for Contract and Commercial Management & Turku University of Applied Sciences, Turku, pp. 75–95 (2008).

Readability scores. Microsoft Office Word Help (2003).

Rodell, Fred, Goodbye to Law Reviews. Virginia Law Review, Vol. 23, November, pp. 38–45 (1936).

Siedel, George J. & Haapio, Helena, Using Proactive Law for Competitive Advantage. American Business Law Journal, Vol. 47, Issue 4, Winter, pp. 641–686 (2010).

Siedel, George & Haapio, Helena, Proactive Law for Managers: A Hidden Source of Competitive Advantage. Gower Publishing, Farnham (2011).

Waller, Rob, Information Design: How the Disciplines Work Together. Technical paper 14. Simplification Centre, University of Reading. http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC14DisciplinesTogether.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012. (2011a).

Waller, Rob, What Makes a Good Document? The Criteria We Use. Technical paper 2. Simplification Centre, University of Reading. http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC2CriteriaGoodDoc_v2.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012 (2011b).

Weatherley, Steven, Pathclearer: A More Commercial Approach to Drafting Commercial Contracts. Law Department Quarterly, October–December, pp. 39–46. http://www.iaccm.com/members/library/files/pathclearer%20article%20pdf.pdf last accessed 11.12.2012 (2005).

Helena Haapio, Business Law Teacher & Researcher, University of Vaasa / International Contract Counsel, Lexpert Ltd.

Acknowledgments

Part of the work presented in this paper was carried out in the FIMECC research program User Experience & Usability in Complex Systems (UXUS) financed by Tekes, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation, and participating companies.

- 1 Rodell 1936, 38.

- 2 Haapio/Siedel 2013, 11.

- 3 Mellinkoff 1963, 24.

- 4 IACCM 2011.

- 5 Nearly 80 per cent, according to Cummins 2003, 4.

- 6 Macneil/Gudel 2001, 2.

- 7 Readability can be defined in many ways and various readability formulas exist. This paper uses readability as an umbrella term for clarity along with functionality, usability, user-experience, and other (good) qualities of contracts that clients can easily understand and act upon. – For making contracts work for clients, see Haapio 2012. For what makes a good document more generally, see Waller 2011b. For differing approaches and criteria used to evaluate the clarity of documents, see also Evans 2011.

- 8 Barton 2012, 108.

- 9 Etzkorn n.d.

- 10 Malhotra 2012.

- 11 Haapio/Siedel 2013, 44–46, 147–149 and Haapio 2012.

- 12 Macneil/Gudel 2001, vii–viii.

- 13 See, e.g., Haapio 2011, with references.

- 14 Hayhoe 2012, 23. – The author calls the first the ornamental approach and the second the holistic approach.

- 15 Albers 2007.

- 16 Two readability formulas, Flesch and Flesch Kincaid, are built into MS Word, as part of Tools / Spelling and Grammar. See Readability scores. Microsoft Office Word Help 2003. The scores MS Word gives for these formulas reflect readability in the narrow meaning of the word, rather than readability as used in this paper: see FN 7 above.

- 17 Pohjonen/Visuri 2008, 82–84.

- 18 Haapio 2011 and 2012.

- 19 Kimble 2006 and 2012.

- 20 Waller 2011a and 2011b and Etzkorn n.d.

- 21 Hetrick 2008.

- 22 Weatherley 2005 and Siedel/Haapio 2010 and 2011.

- 23 Hetrick 2008.

- 24 The project looks into contracting in the Finnish Metals and Engineering Competence Cluster (FIMECC) as part of User Experience & Usability in Complex Systems (UXUS), a five-year research program financed by participating companies and Tekes, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation. See also Haapio 2012.

- 25 See, e.g., Haapio 2010, Siedel/Haapio 2011, and DiMatteo et al. 2012.

- 26 See, e.g., Passera 2012 and Passera/Haapio (forthcoming). The examples are part of a case study carried out in a Finnish company operating in the metals and engineering sector. More prototypes and case studies are underway.

- 27 Passera 2012 and Passera/Haapio (forthcoming).

- 28 For an example, see, e.g., the Wikipedia entry Swim lane, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swim_lane accessed 24.1.2013.

- 29 Haapio 2013 and DiMatteo et al. 2012.