Dr. Hoffman: How many degrees Fahrenheit is 40 degrees Centigrade?

Martin: One hundred and four.

Dr. Hoffman: If the air temperature is 104 degrees Fahrenheit, is that cold, warm, or hot?

Martin: That’s 40 degrees Centigrade.

Dr. Hoffman: Is that hot, warm, or cold?

Martin: That’s 104 degrees Fahrenheit.

Evald Flisar, What About Leonardo? (Act II, Scene 1)

Information technology as such cannot replace the basic mission of the judiciary – adjudication; however, it can help considerably.

(Development Strategy for IT-Supported Court Business Processes, Ljubljana, September 2012, p. 4)

1.

Introduction ^

2.

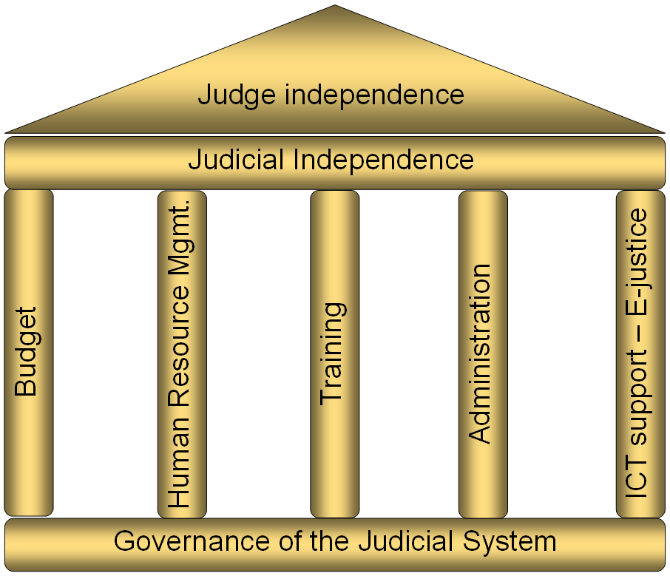

E-justice as one of the core pillars of judicial independence ^

The Development Strategy for IT-Supported Court Business Processes5 (hereinafter: the IT Strategy) defines strategic guidelines and standards for the development of IT support for judicial business processes. According to the IT Strategy, it would have been virtually impossible to achieve exceptional results without the close cooperation of the court management, providers and beneficiaries, and their commitment to the common strategic aims. Information technology as such cannot replace the basic mission of the judiciary – adjudication; however, it can help considerably, particularly by the following:

- optimising business processes on the basis of a functional analysis in planning IT support for a procedure;

- supporting business decision-making and subsequent verification with the use of business data collected by using case management systems (identifying bottlenecks, lengthy tasks, etc.);

- accelerating business processes by using case management systems, for example:

- savings in data entry through the principle of «enter once, use many times»;

- savings due to easier file tracking;

- savings due to the automatic generation of frequent writs (by using verified templates);

- savings due to the optimisation and automation of logistics tasks;

- better organisation of work due to uniform working methods;

- easier access to data in external records that are required in court proceedings;

- easier access and analysis of data collected in relation to individual proceedings6.

3.

Project management organisation ^

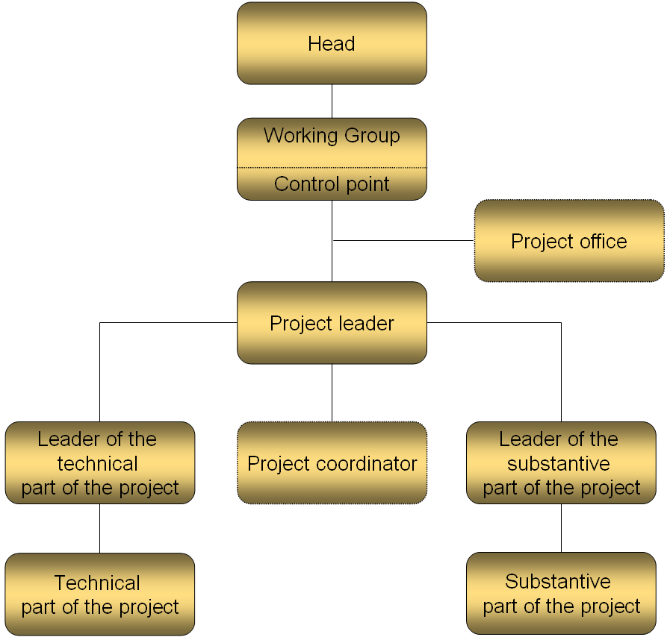

Picture 3: Typical project organisation of work on IT projects8

- the technical part of the project, which deals with technical issues within the project, determines technical standards and solutions, checks the quality of software, and communicates with outsourcers; and

- the substantive part of the project which deals with the functional specifications, user requirements, lists of business processes, and the organisational and legal frameworks.

- it prevents project group members from dealing with a field in which they are not proficient;

- it enables project group parts to meet separately, so that proposals are adopted and enforced more quickly and efficiently;

- it enables the leader of the substantive part of the project to be interpreted as the representative of the client, and the leader of the technical part as the representative of the service provider, and in this way facilitates a distinction between their obligations.

4.

E-justice projects ^

Although in both the organisational and technical parts, the development and implementation of information systems in the Slovene judiciary is independent, it is essential that in specific parts development is linked or open to other systems within (G2G11) or outside (G2B12, G2C13) of the public sector. The basic purpose of the system is naturally to support the internal business needs, but the judiciary as a public service cannot be isolated but is closely connected to the outside environment. The expectations and needs of external beneficiaries must be considered in this regard. Strategic guidelines in the development of IT solutions reflect the Supreme Court’s commitment to the e-justice concept14. Analysis of individual segments of information systems show that common objects or features appear in all information subsystems. The common objects or features dictate a uniform approach in the concepts of systems, both on the level of analysis and design, on one hand, and on the level of implementation and maintenance, on the other15.

- a focus on necessary legal changes directed at the implementation of e-services and interoperability;

- a focus on organisational changes and improvements directed at the concentration and centralisation of business functions and business processes and the improvement of business processes directed at better court performance;

- a focus on technical changes directed at the implementation of the key building blocks of e-services that are common to every IT system in the judiciary.

- the Automated System for Enforcement on the Basis of an Authentic Document (COVL); and

- the Judicial Data Warehouse and President’s Performance Dashboards.

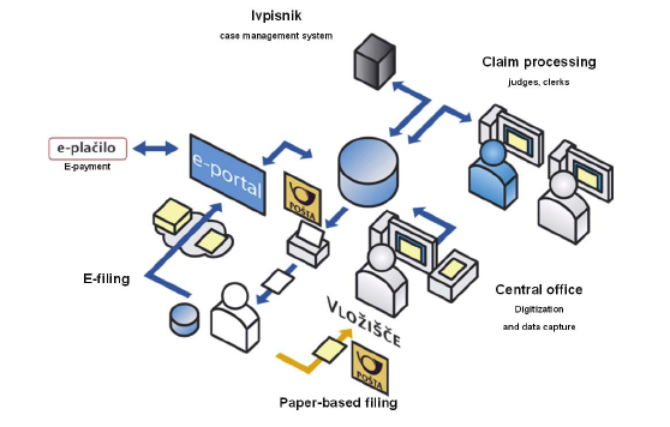

These were the reasons that led the Supreme Court to the decision to launch the Project «The Central Department for Enforcement on the Basis of an Authentic Document (COVL)». COVL is an Slovene acronym for Centralni Oddelek za Verodostojno Listino. The Project was partly performed also within the international EU Transition Facility Twinning Project «Backlog Mitigation in Enforcement Procedures» in cooperation with the German Foundation for International Legal Cooperation17 and was divided into legislative, organisational, technological, and public relation components. The strategic goal of the project was to reduce judicial backlogs and improve the efficiency of courts in enforcement procedures. The first business objective set the disposition time to two working days and the second objective was to reduce backlogs by 15% by the end of 2007.

- e-filing19;

- the centralisation of business processes;

- access to external registers;

- case files would only be in electronic form;

- central printing by an external service provider.

Picture 4: Automated System for Enforcement on the Basis of an Authentic Document25

- concentration and centralisation of the business process – The business process, which had previously (until the end of 2007) been performed at 44 locations by more than 250 judges and court staff, and with an influx of less than 115,000 cases, is now performed at one location by 5 judges and 65 court staff with an influx of more than 210,000 cases in 2012.

- e-filing – In 2012 more than 99% of applications for enforcement were filed electronically (55.37% on-line and 43.81% as bulk filings).

- accelerating the business process – In nearly 60% of cases, the enforcement order was issued within two working days of receiving a complete application for enforcement, while 75% of enforcement orders were issued within five working days of receiving a complete application for enforcement.

- the e-case file – The Central Department for Enforcement on the Basis of Authentic Documents operates practically paperlessly, with only an electronic case file, as all incoming cases not sent through the portal are digitalised (scanned) and transferred to the case management system.

- interoperability – Automatic collection of data (G2G) on a debtor’s assets and other information (from the company register, the business register, bank accounts, the debtor’s employer, the land register, the clearing house register, the tax register, the health insurance register, the register of spatial units, and the register of citizens) was introduced, which considerably improved the quality of the process and unburdened human resources.

- bulk printing – All documents delivered through the case management system are centrally printed and automatically put in envelopes not within the court building but by an external service provider (outsourcer) selected through a pubic procurement procedure. A special common building block also useable by other systems (the land register, the insolvency case management system) was introduced in this regard.

- modular design – some modules (bulk printing, e-filing, access to external registers) which were introduced into the system are used also by some other case management systems implemented in the court business process (insolvency, the land register).

- reducing backlogs –Despite the (nearly 100%) higher influx of cases, backlogs were considerably reduced after the implementation of the new concept. The number of pending enforcement cases on the basis of authentic documents was reduced by nearly 42% (from 239,100 as of 31 December 2007, to 139,700 as of 30 September 2013) and the number of all pending cases at Local Courts was reduced by more than 42% (from 424,900 as of 31 December 2007, to 244,800 as of 30 September 2013). This also confirmed the Supreme Court’s strategic approach to intervening in fields that are «labour intensive» in order to unburden judges and court staff, re-engineer the business process in the sense of lowering the level of decision-making to the lowest possible level, and enable them to focus on the substantive part of the process.

- reusability – An approach similar to the «Automated System for Enforcement on the Basis of an Authentic Document (COVL)» Project was also implemented in the «Redesign of the Land Register» Project in 2010, with the exception that 44 Local Courts continued to be competent to decide in the registration procedure, but with the abrogation of territorial jurisdiction concerning the filing of applications and jurisdiction according to lex rei sitae. This enabled the assignment of cases to clerks on the basis of the amount of their workload and balancing the workload of the land register personnel throughout the country. Electronic filing of all applications and their attachments through the unique E-Justice Portal for all professional users (notaries, attorneys-at-law, real estate companies, and certain state administrative bodies) became mandatory. Furthermore, the exclusive jurisdiction of the Higher Court in Koper to hear appeals, which ensured unified case law, was introduced.

4.2.

The Judicial Data Warehouse and the President’s Performance Dashboards ^

It is not only about statistical data analysis. It is also about a change in the habits, work methods, and mentality of judges and other employees at the courts.

Alenka Jelenc Puklavec – former Head of the Registry Department of the Supreme Court

- how to integrate the set of data from the various above-mentioned systems and sources into one unified data model and database; and

- how to meet the different needs and expectations of different stakeholders in the judiciary, the entire organisation of justice, and also the public.

- annual publications;

- the President’s Performance Dashboards;

- a new Court Management Methodology; and

- a new Human Resource Balancing Methodology.

4.2.1.

Annual publications ^

- the annual work programme; and

- the annual report on the performance of the court.

4.2.2.

The President’s Performance Dashboards ^

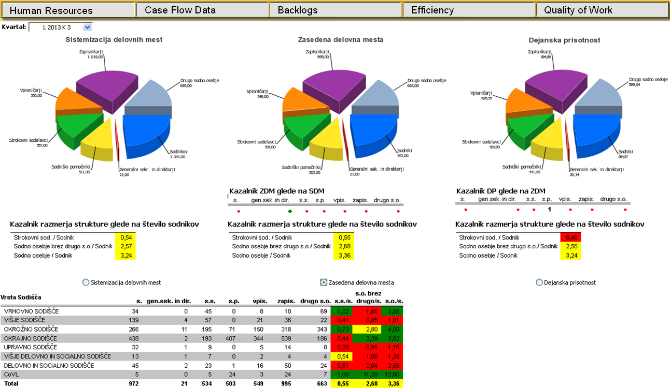

- Human Resources

- Case Flow Data

- Backlogs

- Efficiency

- Quality of Work

4.2.3.

New Court Management Methodology ^

A Court Management Methodology was drafted in order to implement and also monitor the six-year strategic programme of the Supreme Court President. The main objective of the Methodology is to improve the quality and efficiency of the Slovene judiciary. The Methodology was accepted as a standard and uniform manner of reporting. Five basic fields of court management were defined, similar to the President’s Performance Dashboards, but more thoroughly analysed by means of business intelligence tools for every particular court and group of comparable courts:

- human resources;

- productivity;

- workload;

- pending old cases;

- quality of work.

For the year 2013, a set of seven priorities were identified based on analyses of key court performance indicators as key areas for improving the performance of the Slovene judiciary31. A common characteristic of all seven priorities is that they are focused on the business targets that were identified as critical areas for ensuring better performance of the entire judiciary and also for meeting the expectations for a better judiciary of the professional and lay public. On the other hand, the focused and transparent operation of the entire judiciary through the presentation of the mission, vision, and fundamental values increases trust in the judiciary, which is of utmost importance for public support and confidence. Concrete projects in all areas of court operation are performed based on accepted priorities.

4.2.4.

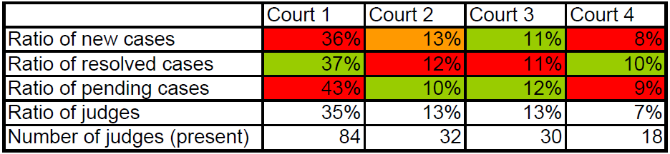

Balancing human resources ^

- Courts shall have sufficient support of judges and court staff in order to control the influx of cases (the clearance rate should be close to 100%);

- Courts with an increased number of pending cases shall temporarily increase the number of judges and court staff in order to reduce the number of pending cases – the target was set at a 5% decrease in backlogs in a given year;

- The Supreme Court shall have a virtual «Pool of Human Resources» in order to support individual initiatives regarding backlog mitigation at particular courts.

5.

Conclusion ^

Rado Brezovar, Senior Adviser to the President of the Supreme Court, Supreme Court of the Republic of Slovenia, Tavčarjeva 9, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia, rado.brezovar@sodisce.si, http://sodisce.si/.

- 1 The project Automated System for Enforcement Based on Authentic Documents (COVL) [Slovene: Centralni Oddelek za Verodostojno Listino] was given special mention in the 2010 Crystal Scales of Justice competition. The Judicial Data Warehouse and Performance Dashboards Project was given special mention in the 2012 Crystal Scales of Justice competition.

- 2 Twinning is an instrument for cooperation between the Public Administrations of EU Member States (MS) and of beneficiary countries. Beneficiaries include candidate countries and potential candidates for EU membership, as well as countries covered by the European Neighbourhood Policy (http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/tenders/twinning/index_en.htm).

- 3 E.g. the E-Justice Portal, the European Payment Order, the EULIS Service – the European Land Information Service).

- 4 Development Strategy for IT-Supported Court Business Processes, Ljubljana, September 2012, p. 6.

- 5 The Users» Council adopted the last IT Strategy on 28 September 2012.

- 6 Development Strategy for IT-Supported Court Business Processes, Ljubljana, September 2012, pp. 4 and 5.

- 7 Standard software packages are used in the operation of courts: Open Office 3.0, standardised centralised case management systems for particular types of court procedures (criminal, civil, enforcement, misdemeanour), the use of service modules based on SOA, and the standardised legal information system.

- 8 Development Strategy for IT-Supported Court Business Processes, Ljubljana, September 2012, p. 8.

- 9 With their written consent, judges may be permanently transferred to another court or another body (transfer) or temporarily assigned to another court or another body (assignment) (Judicial Service Act, Art. 4, Para. 3). Assignment may last no longer than three years, and may be repeated with the consent of the assigned judge (Judicial Service Act, Art. 71, Para. 4).

- 10 The Enforcement and Securing of Civil Claims Act [Slovene: Zakon o izvršbi in zavarovanju], the Civil Procedure Act [Slovene: Zakon o pravdnem postopku], the Land Register Act [Slovene: Zakon o zemljiški knjigi], the Court Register of Legal Entities Act [Slovene: Zakon o sodnem registru], and the Financial Operations, Insolvency Proceedings and Compulsory Dissolution Act [Slovene: Zakon o finančnem poslovanju, postopkih zaradi insolventnosti in prisilnem prenehanju] have all introduced e-justice features in the past seven years.

- 11 G2G – Government to Government data communication.

- 12 G2B – Government to Business data communication.

- 13 G2C – Government to Citizen data communication.

-

14

The IT Strategy defines eight strategic guidelines in the development of IT solutions (p. 13 et seq.):

1. Uniform architecture of IT solution development;

2. Modular design of IT solutions;

3. Reusability;

4. Interoperability;

5. A standard data exchange format;

6. Standard formats for processing and saving documents;

7. Programme code ownership;

8. Programming languages and the programming environment; -

15

The IT Stategy defines them as key building blocks of e-services in the judiciary and specifies the following (p. 18 et seq.):

1. An electronic filing (e-filing) system;

2. An electronic mail register;

3. An electronic case file. - 16 For more details, see: Gregor Strojin, Central Department for Enforcement on the Basis of Authentic Documents – Building Interoperability in European Civil Procedures Online Case Study – Slovenia, Ljubljana, 20 April 2012 – http://www.irsig.cnr.it/BIEPCO/documents/case_studies/COVL%20Slovenia%20case%20study%2025042012.pdf.

- 17 The Project was carried out from 2004–2008.

- 18 E.g. the payment order in Germany – http://www.mahngerichte.de/ and the on-line money claim in the UK – https://www.moneyclaim.gov.uk.

- 19 The first concept of e-filing in the European judiciary was presented by Dr. Martin Schneider at the 10th Colloquy, Ankara, 1992, «Present state and further development of legal data processing systems in European countries». E-filing for small clients through the web portal and for bigger clients using B2G concepts of bulk filing is supported in the Slovene concept.

- 20 Official Gazette, No. 52/2007, Arts. 16a, 23, 105, 105b, and 132 (use of the e-file, e-signature, e-filing, e-delivery, and access to the case management system was introduced).

- 21 Official Gazette, No. 115/2006, Arts. 6a, 29.

- 22 Official Gazette, No. 127/2006, Art. 99a.

- 23 Official Gazette, No. 115/2006, Art. 6a.

- 24 Official Gazette, No. 45/2008, Art. 13.

- 25 Gregor Strojin, Central Department for Enforcement on the Basis of Authentic Documents – Building Interoperability in European Civil Procedures Online Case Study – Slovenia, Ljubljana, 20 April 2012 – http://www.irsig.cnr.it/BIEPCO/documents/case_studies/COVL%20Slovenia%20case%20study%2025042012.pdf p. 30.

- 26 Financial indicators (e.g. different costs per case) are in the phase of implementation.

- 27 Beside these outputs, also standard necessary deliverables such as statistical reporting for different beneficiaries (e.g. the Supreme Court, the Ministry of Justice, the Judicial Council, university faculties, and other research institutions) should not be neglected.

- 28 The Courts Act, Paras. 60a and 71a.

- 29 The Courts Act, Para. 71a.

- 30 The Courts Act, Para. 60 a.

-

31

First Priority: «Court management»;

Second Priority: «Resolving older pending cases»;

Third Priority: «Time standards»;

Fourth Priority: «Unburdening judges»;

Fifth Priority: «Balancing human resources»;

Sixth Priority: «Criminal procedure»;

Seventh Priority: «Special programmes in critical courts». - 32 http://www.sodisce.si/sodna_uprava/statistika_in_letna_porocila/prioritetna_podrocja/.

- 33 In December 2005, the Ministry of Justice launched the «Lukenda Project». In order to reduce disposition times, which in Slovenia, according to the European Court of Human Rights, were not in accordance with Article Article 6 § 1 (the right to a fair hearing within a reasonable time), the Ministry engaged additional judges and court staff, but not equally according to the real workload of individual courts.

- 34 In accordance with the most recent amendments of the Courts Act in July 2013, the Supreme Court shall determine the number of judicial posts and court staff for every particular court.