[21]

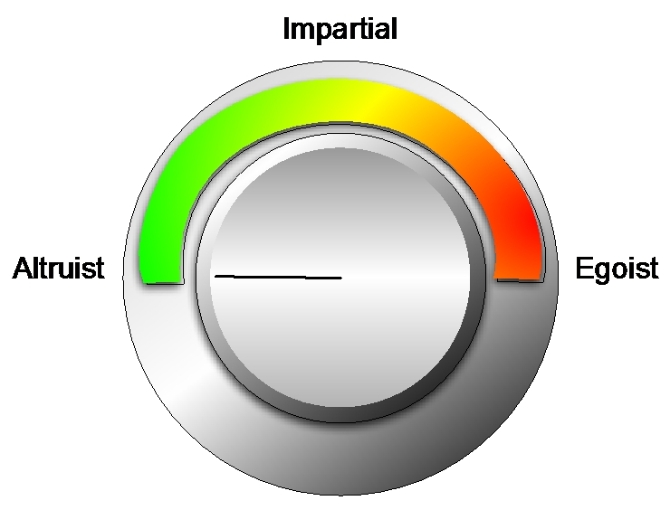

Let us now imagine that the AV is fitted with an additional control, the «Ethical Knob» (see Figure 1).

[22]

The knob gives the passenger the option to select one three settings (see Figure 1):

- Altruistic Mode: preference for third parties;

- Impartial Mode: equal importance given to passenger(s) and third parties;

- Egoistic Mode: preference for passenger(s).

[23]

In the first mode (altruistic), other people’s lives outweigh the life of the AV passenger. Therefore, the AV should always sacrifice its own passenger(s) in order to save other persons (pedestrians or passersby).

[24]

In the second mode (impartial), the lives of AV passenger(s) stand on the same footing as the lives of other people. Therefore, the decision as to who is to be saved and who is to be sacrificed may be taken on utilitarian grounds, e.g., choosing the option that minimises the number of deaths. In cases of perfect equilibrium (where the number of passengers is the same as that of third parties), there might be a presumption in favour of passengers, for the third parties, or even a random choice between the two.

[25]

In the third mode (egoistic), the passenger’s life outweighs the lives of other people. Therefore, the AV car should act so as to sacrifice pedestrians or passersby rather than its own passenger.

[26]

The functioning of the knob, at least in principle, can be extended so as to include kin altruism, so that, in the Egoist mode, the AV will always act to save not only the passenger, but also his or her family or significant others.

[27]

Let us now assume that an AVs is endowed with the Ethical Knob.

[28]

The allocation of liability would be in principle be the same as for manned cars. However, since the car’s behaviour has to be chosen beforehand, there should be no difference between omissive behaviour (letting the car proceed in its course) and active behaviour (swerving to avoid pedestrians on the street).

[29]

In scenario (a) the passenger’s life is not at stake; therefore the setting of the knob does not matter. Consequently, the AV’s behaviour should be based on utilitarian grounds: it should follow the trajectory that minimises the number of deaths. In fact, since the knob’s setting is decided in advance relatively to the accident, a choice to keep going and kill several pedestrians rather than a single passerby cannot be justified according to a moral stance that condemns the active causation of death more than the omissive failure to prevent it.

[30]

In scenario (b) and (c), by contrast, the passenger’s life is at stake; therefore the car’s behaviour would depend on the setting of the knob. Moreover, since the passenger’s life is directly at stake – and the passenger is aware of this possibility when setting the knob – the general state-of-necessity defence will apply, excusing the driver’s choice to prioritise his or her life.

[31]

More specifically, in scenario (b) we could have the following behaviour, depending on the knob setting.

[32]

(1) If the knob is set to egoistic mode, the AV car will always act to sacrifice pedestrians or passersby in order to save its own passenger. (2) If the knob is set to impartial mode, the AV will take a utilitarian approach, thus minimising the number of deaths (and deciding according to a predefine default or randomly, when the number is the same for both choices). (3) If, finally, the knob is set to altruistic mode, the AV will sacrifice its own passenger in order to save pedestrians or passerby.

[33]

In scenario (c) the AV’s behaviour will be the following. (1) If the AV is set to egoistic mode, it will always save its own passenger. (2, 3) In impartial mode, as well as in altruistic mode setting, the AV will sacrifice its own passenger in order to save several pedestrians.

[34]

In scenarios (b) and (c), the applicability of the state-of-necessity defence will exclude criminal liability, but the passenger could still be civilly liable for damages and be required to pay compensation. In this regard, the different knob settings presented above may affect third-party insurance. Presumably, the insurance premium will be higher if the passenger chooses to sacrifice other people’s lives in order to save him/herself.

[35]

We have so far assumed that the knob has just three settings: egoism (preference for the passenger), impartiality, and altruism (preference for the third parties). These preferences are sufficient to determine a choice, assuming a deterministic context, i.e., that in every possible situation at hand it is certain what lives will be lost, whether the car keeps a straight course or swerves.

[36]

In real-life examples the situation may be much fuzzier: each choice (holding a straight course or swerving) may determine ex ante only a certain probability of harm (for the passenger or for a third party).

[37]

To address these situations we need a knob that allows for continuously changing settings, each one determining the weight of the life of the passenger(s) relative to that third parties.

[38]

Besides, in our scenario we have assumed that choices are between the life of a single passenger and that of a single third party. The model should be extended to cover cases where more than two lives are at stake.