1.

Introduction ^

The constant and dynamic development of new technologies contributes to the growth of its importance in the everyday life of society. There can be observed a significant influence of technology on the shape of reality. The constant evolution of devices and technological solutions has an impact on the formation of society, relations between various entities, ways of conducting business activity and on other spheres of human activity. Over time, changes caused by technological development also have an impact on the shape of legal norms in a given legislation.1 It can be observed that the most significant influence on the current shape of the existing legal acts is exerted by those devices whose main purpose is to enable interpersonal communication2. In addition to traditional verbal communication, electronic communication has become equally popular (or even more popular) in every sphere of human activity: Social conversation, maintaining family ties, running a business, pursuing scientific activities and other. Hence, the question arises whether the use of new technologies that enable effective communication can take place also in inheritance law.

A will can be identified as the last act of communication between the deceased and his relatives. In his last will, the testator passes and communicates to the living ones his last will regarding the disposition of his property. However, at this point it is difficult to imagine that such communication could take place through the use of new technologies, in particular audio-video technologies.

Polish inheritance law still remains a set of traditional regulations, grounded on the basis of legal constructs derived from the Roman law. Taking into account the amendments that have affected other sections of the Polish civil law (e.g. the introduction of an electronic form of legal action), it can be concluded that inheritance law has not yet become a beneficiary of any significant changes in the implementation of technological solutions.

In view of the above, the following questions can be asked: Does Polish inheritance law need to be changed? Should inheritance law only be based on traditional solutions? Should the legislator create opportunities for the use of new technologies in inheritance law? Does making a will in electronic form bring more threats than opportunities?

The inability to stop technological development and its impact on the shape of the amended legal acts will sooner or later have to affect the issue of inheritance law.

This article focuses on the analysis of the issue of e-wills. The hypothetical analysis as to the shape, form and possibility of future regulation of e-wills in the Polish law, or more broadly in the European law, has been enriched with case law examples from countries where making the will in electronic form is legally possible. In this report, the dominant legal system is the Polish legal system. Hence, based on Polish regulations, the validity of wills in Polish law is being considered. Hypothetical considerations on the form of the e-wills focus mainly on formal analysis in the context of video-last will. All the work is summarized in surveys (conducted on a national and European scale), legislative proposals and prepared proposals.

2.

Electronic last will in selected jurisdictions ^

In the present times, electronic last will is no longer just an abstract concept, a hypothetical reflection on the future. E-wills are already being drawn up in the various legal systems around the world. However, the existing loopholes in the law or the lack of regulation of this form of disposition of property upon death results in an increase in the number of cases submitted to courts, which concern this form of drawing up the last will.

The several representatives of the doctrine and the legal sciences of the various legal systems – civil law and common law – draw up different catalogues on the form of dispositions of property upon death, which fall within the concept of e-will.

For example, law experts in the United States distinguish three forms of e-will3:

- Offline electronic wills – they can be considered a modern, modernised version of holographic wills. The testator writes down his will on an electronic device (e.g. a computer) and then the file is saved on a hard disk (usually not printed). Typically, the last will is written down using a graphics tablet, which allows to copy handwritten text to a certain extent.

- Online electronic wills – these are created by the testator and then stored by third parties on servers developed and delivered to testators.

- Qualified Custodian Electronic Wills – these are wills created by a third party – a «qualified custodian» who undertakes, in the course of his business activities, to create, store and fulfil the last will of the testator. The main responsibility of the entrepreneur is to simultaneously organize in front of the webcam the necessary persons to guarantee the validity of the will – witnesses, notary public.

The United States of America is a precursor to the legal admission of electronic wills. For example, one may indicate the amendment of the statute of the State of Nevada adopted in 2001, which took place in 20174. This amendment aimed at two main issues: The introduction of a definition of the electronic will and the addition of provisions governing the admissibility of legal fiduciary wills.

Under the provisions of the Statute of the State of Nevada, the electronic will is a will that is written, created and maintained in an electronic register, contains the date and electronic signature of the testator, as well as one or more of the characteristics of the testator’s authenticity is stored in such a manner that there is only one authorised copy that is stored and controlled by the testator or a designated custodian, so that each attempt to change its contents is readily identifiable, and so that each copy of the authorised will is easily identifiable5.

3.

The e-will in the international jurisprudence ^

Disagreements about the validity of the e-will are increasingly becoming a matter of concern for the courts. In recent years, the judiciary in different countries has faced problems in recognising or not recognising the testator’s last will expressed in electronic form.

One of the first cases concerning the validity of the e-will was the MacDonald v The Master case, which took place in South Africa in 20026. In the latter case, the testator committed suicide in 2000, but had previously drawn up and kept a note by hand of the following text: I, Malcom Scott MacDonald, ID 5609065240106, hereby declare that my last will can be found on my computer in IBM in the catalogue C:/windows/mystuff/mywill/personal. The problem was that the document drawn up by the deceased was not signed. The fact that the computer was protected by a password which was written down, sealed and blocked was put forward as evidence in the case. This was a sufficient presumption that nobody except the deceased had access to his computer, so nobody except him could enter and write the contents of his last will and save it on his hard disk. On the basis of the evidence gathered, supported by confessions of IBM employees confirming the impossibility of access to the computer by others, the court ruled that a document prepared by the deceased may be considered as a valid will7.

One of the most controversial decisions was Yazbek against Yazbek case, which was brought in the Supreme Court of the State of New South Wales in Australia in 20128. This concerned the validity of the will of the deceased Daniel Yazbek drawn up in the Microsoft Word in 2009. The testator was found dead on 19 September 2010 by his mother on the Queens Park estate. The police secured all the personal belongings of the deceased, including his laptop, which was secured by the password. Thanks to the help of a family member who indicated the likely content of the password, it was possible to access to the files of the deceased. Among them, a file entitled Will.doc was found under the address C:/users/danielyazbek/documents. It contained the last will of the deceased and was signed «Daniel Yazbek». However, it was not an electronic signature, but the characters entered from the keyboard. Although the password to the computer was not complicated, the family member could guess it using the trial and error method, the experts after analysing the metadata did not find any possibility of interference with the content of the document by third parties. In this respect, the court ruled that Will.doc is the deceased’s last will and should therefore be treated as a valid will.

The Estate of Javier Castro9 was the case which initiated e-wills case law in the United States. In this case the problem faced by the Ohio court was whether an oral will given by the testator in hospital was valid, with the deceased’s brother writing the statement by using a stylus on a mobile device, a tablet and then signing it (also with a stylus) by the testator. The signature was placed later, in another hospital, in the presence of witnesses – the deceased’s brothers – who also signed the document. After Javier’s death, his will was printed and submitted to the court for assessment. The court faced a dilemma as to whether the document prepared in such a way could be considered as written or only signed by the testator. Having assessed the circumstances of preparing the content of the disposition, the court decided that the electronic document submitted to it meets the requirements of a written form. Moreover, the court’s judgment was also based on the testimony of six witnesses who confirmed that the testator was aware of the will and signed the will. In conclusion, the court accepted the electronic document as a valid last will.

Another interesting case pending in 2013 before Queensland’s Supreme Court in Australia was the Yu case10. In the described circumstances of the case, the testator committed suicide. However, he had previously created a series of documents on his mobile phone, the iPhone. Most of these documents were his last farewells, but one of them was expressed as his last will. Australian law allows, under Section 10 of the Succession Act of 198111, for the admission of the document containing testator’s last will in an unregulated form on the basis of Article 18 of the said act, if the court is confident that the testator was intended to make the valid will. That decision was taken in the factual circumstances relied on. A document stored in the memory of a mobile phone was considered as a will.

In 2017, Queensland’s Supreme Court in Australia was again required to take a position on the validity of the e-will. In the case of Nichol v Nichol12, an unsent text message, SMS, had to be evaluated. The mobile phone, which was found in the place where the body of the deceased Mark Nichol was located, contained an unsent message which contained the last will of the deceased. In the text of the message it was possible to read who was entitled to receive particular property components. The deceased also provided the PIN number for his card. The whole was signed with the words «my will». The Court ruled that such a message was exhaustive of the characteristics of a valid last will.

4.

Last will in the Polish legal system – terminology, validity ^

Considerations regarding definitions and the essence of a last will should begin with the statement that in the world the term «last will» is not understood uniformly13. The difference in understanding this concept is particularly noticeable in the systems of continental law (civil law) and Anglo-Saxon law (common law). In the understanding of civil law, a will is treated as a unilateral, revocable legal action made by the testator in a legally prescribed form. In the common law system, we have a wider understanding of a will14, where it is not always associated with a single document. In Anglo-Saxon law, a will is made up of all documents drawn up by the testator that contain the last will of the testator15.

As the legislative practice shows, legislators rarely decide to draw up a legal definition of the institution of a last will. However, in some legal systems one can find such a definition. For example, the Italian legislator in the legal act of 16 March, 1942, Codice Civile16 (Civil Code) decided to make a legal definition of a last will. It is found in Article 587 and states as follows: «Last will is a revocable act whereby a person posthumously disposes of all or part of his or her property17. There is no legal definition of the concept of a last will in Poland. The provisions concerning this form of disposition of property upon death can be found in the Civil Code of 23 April 196418. The Polish legislator only points out that a last will is the only option to make a legal disposition of property in the event of death (Article 941). It follows therefore that the development of this definition has been left to the doctrine. Most of the doctrine assumes that the term «will» in inheritance law and inheritance proceedings, contrary to the principle of linguistic rationality, has different meanings.19 This means that the understanding of the term «will» depends on the situation. However, a dichotomous division of understanding of this concept is widely accepted. Depending on the context, this term can be considered as a unilateral legal act (used by a natural person (testator) to regulate primarily his economic situation after his death20) or a document21 (contains a disposition of property dispatched by the testator22). A different view is also adopted. According to J. Gwiazdomorski, last will is always a legal act23. In view of the above, the following definition of a last will can be made in favour of the dominant view: A will is a legal act, an act of will by which a testator makes a disposition of his property upon death, usually in the form of a document.

Regardless of the understanding of the term «will», whether on the level of common law and civil law systems or disputes in the Polish doctrine, all representatives of law science unanimously point to a catalogue of characteristics of each will understood as a legal action. These include: Exclusivity, unilaterality, mortis causa effectiveness, personal character, formalisation and revocability24. Exclusivity, as one of the features of the last will, can be interpreted on the basis of Article 941 of the Polish Civil Code, which states that a disposition of property upon death can only be made by a last will. The next article (942) points to the unilateral nature of the last will. A will can only be made by a single testator, and it may contain dispositions of only one testator. This is a strong emphasis on the prohibition of drawing up joint wills (e.g. by both spouses). Yet another feature of a last will – mortis causa effectiveness, indicates that the legal act is intended to have effects only after the moment of the death of the person who carries it out. The introduction of a provision constituting a prohibition on the preparation and dismissal of a will by an attorney (Article 944 § 2 of the Polish Civil Code) allows for the interpretation of another feature of a last will, namely its personal character. This is to further ensure the freedom of the testator to take up and express his will, and to protect against the falsification of acts of last will25. Formalization of a will is based on the admissibility of performing this legal act only in one of the forms regulated by the provisions of the Polish Civil Code (Articles 949 – 954). In the event of a failure to comply, a violation of at least one of the requirements specific to a given form of will leads to an absolute invalidity of the legal act with the ex tunc effect. The testator may use various forms of will, which may be divided into general forms (regulated by Articles 949 to 951 of the Polish Civil Code) and special forms (Articles 952 to 954 of the Polish Civil Code). The importance of the principle of equality of the form is relevant to the choice of the form of the last will. It assumes that the last will made in each form will have the same effect, none of the forms will have stronger (weaker) legal effects than the other. The last feature of a will – revocation – is based on granting the testator the option to revoke his disposition. This is possible because the testator’s declaration of will is not addressed to a specific addressee, and the dispositions included in the last will have no legal effect until the death of the testator. Hence, a testator may, by exercising his testimony freedom, at any time revoke both the entire will and the individual provisions of a will26.

In order to have mortis causa effects, the last will must be properly drawn up and therefore valid. With regard to the validity of dispositions of property upon death, the legislator has developed the necessary requirements, which can be divided into substantive and formal requirements.

Material requirements are closely related to the testator, his or her characteristics and behaviour.

The basic condition of the material premises is the capacity to make a will. Mortis causa activities may be carried out only by persons who have the capacity to do so27. A capacity to make a will and, therefore, the capacity of a testator to make a valid last will, is a particular case of legal capacity 28. The legislator states in Article 944 § 1 of the Polish Civil Code that a last will can be made or revoked by a person who has full legal capacity to act. Hence, a contrario, a will may not be made by a person without full legal capacity or with a limited legal capacity. Limited legal capacity is vested in a partially incapacitated adult person (Article 16 of the Polish Civil Code), as well as in persons between the age of 13 and the attainment of majority (Article 11 in connection with Article 12 of the Polish Civil Code). Additionally, under the provisions of Article 549 of the Act of 17 November 1964, of the Polish Code of Civil Procedure29, a person for whom a temporary adviser has been appointed has a limited capacity to perform legal acts on an equal basis with a partially incapacitated person. Persons who are under thirteen and persons entirely incapacitated (Article 12 of the Polish Civil Code) have no legal capacity. In view of the above, it should be concluded that only an adult who is not incapacitated has a capacity to make a last will (Article 11 of the Polish Civil Code). When defining the age of majority, it should be taken into account that the Polish legislator provided for two possibilities of obtaining it, namely by reaching the age of 18 (Article 10 § 1 of the Polish Civil Code) and through marriage concluded by a minor (Article 10 § 2 of the Polish Civil Code). A testator, in order for a will to be valid must have a capacity to make a will at the time when it is made.

Another material premise for a validity of a last will is the existence of animus testandi. This concept stands for the willingness to make a will. Therefore, it is not identical with a concept of capacity to make a will, although like a capacity to make a will it is a necessary premise for the preparation of a valid will30. A capacity to make a will is an abstract concept. A natural person may have it or not at a given moment. Animus testandi has a specific character31. This means that it is subject to an assessment of its existence at a particular point in time in the life of the individual concerned. This institution was a subject matter of the Polish Supreme Court. In its Ruling of 18 February 1999 (I CKN 1002/97) 32 the Polish Supreme Court clarified the conditions of validity of animus testandi. First of all, the testator must be aware of the fact that the actions he or she has taken aim to be his or her last will. Moreover, on the testator’s part there must be an intention to make a will, and the testator must make a disposition deliberately.

The last of the discussed material premises are defects in the declaration of will, which may occur while making a last will. They have been regulated in Art. 945 of the Polish Civil Code. The exegesis of the said legal provision allows to create a closed catalogue of defects which may affect the testator’s statement. It is worth mentioning that the catalogue prepared by the legislator is similar in its construction to the catalogue of defects in declarations of will regulated in the general part of the Polish Civil Code (Articles 82 – 87). However, in the case of a last will, deceptive activities were excluded from the legislation. It is motivated by the fact that the testator does not make a declaration of will to another person. It shall therefore be impossible to make such a false declaration with the consent of the other party33. The first of the defects that may be affected by a testator’s statement is a state precluding a conscious or free decision and declaration of intent. For various reasons, the testator may be in a state that limits his or her consciousness or freedom. First of all, such disorders may result from mental illness or debility, but also from alcohol abuse or high fever. The testator’s awareness can be confirmed by the cumulative occurrence of the following circumstances: He or she understands the essence of a will and its effects, is able to identify the property which the testator is authorised to dispose of, has the knowledge of persons who may be heirs, rationally plans dispositions34. The testator’s freedom may be restricted at two levels. First of all, it may result from the future testator himself (a serious illness). However, a freedom to make a will may be limited also as a result of third party coercion. The second defect in a declaration of intent is an error. An error can be defined as an inadequate reflection in the awareness of the actual state of affairs35. An example of an error could be the testator’s mistaken belief that the person to whom disposition is made is related to him. However, declaration of intent will be defective only if it is made under the influence of a substantive error. In order to understand the essence, the significance of a material error should be based on the construction of Art. 84 § 2 of the Polish Civil Code. On the basis of this provision, the occurrence of the material error justifies the assumption that if the testator did not act under the influence of an error, he would not submit a statement of a given content. The last defect in a declaration of intent is a threat. A threat can be equated as a prelude to doing something wrong to someone in case he fails to perform the required legal action36. It is worth mentioning that the understanding of threat as a defect in the declaration of will on the basis of Article 945 § 3 of the Polish Civil Code differs from the meaning adopted in Article 87 of the Polish Civil Code. When formulating the wording of Article 945 of the Polish Civil Code, the legislator – in comparison to Article 87 of the Polish Civil Code – resigned from specifying threat, in the form of adding the adjective «unlawful». This means that a testator can claim both an unlawful threat (e.g. a threat of property damage) and a legally permissible threat (e.g. the threat of the initiation of debt enforcement)37.

Formal premises for the validity of a last will are explicitly determined by the legislator in the provisions of the statute. They are based on the assumption that in order to have its effects (the validity of dispositions), a last will must be made in the legally prescribed form. Thus, the testator’s declaration of intent may not be made by any means in discretionary manner38. It must be submitted in one of the forms provided for by law. The legislator specified and created the closed catalogue (numerus clausus) of the forms of last wills. If the form of a will is not observed, or if a will is made in a form that is not legally regulated, it will in principle result in the invalidity of the legal act. Pursuant to Article 73 § 2 of the Polish Civil Code, if the legislator stipulates a different specific form for a legal act, an act performed without this form is invalid. As stated above, a will is a legal act which must be made in a legally specified form. The above mentioned pain of nullity of a legal act (ad solemnitatem) was additionally confirmed by the legislator in a separate provision in relation to the last will. Article 958 of the Polish Civil Code provides that a last will which has been made in breach of the accepted provisions is void, unless the law provides otherwise. Ratio legis of confirming the reservation of ad solemnitatem form in relation to the form of the last will is aimed directly to draw attention to the fact that the activity performed without keeping this form is absolutely null and void39. In conclusion, the current legal state in Poland does not provide for the use of new technologies, when making a valid and effective last will. Drafting the last will, for example, in sms or email form, would be – in the light of the above provision – influenced by the legal defect, resulting in such a last will being null and void.

5.

The forms of the last will in the Polish law – an oral last will in the light of new technologies ^

The provisions concerning the form of the last will are included in the Polish Civil Code (Articles 949 - 958). As has already been mentioned, one of the conditions for the validity of the last will is that it should be drawn up in a legally admissible form. In the above mentioned provisions, the legislator closed the catalogue of the allowed forms of last wills. It consists of two categories: general wills (Articles 949 to 951 of the Polish Civil Code) and special wills (Articles 952 to 954 of the Polish Civil Code). General wills are usually made in ordinary, typical circumstances. The possibility of drawing up a special will is limited to extraordinary circumstances40.

A holographic (hand-written) last will is the basic type of ordinary will. The testator may draw up his will in such a way that he writes it down in full by hand, signs it and affixes it with the dates (Article 949 § 1 of the Polish Civil Code). The basic premise for the validity of such a last will is that it must be handwritten. This is motivated mainly by the fact that a handwritten document is more difficult to forge than only a forged signature41. It is worth mentioning that the requirement of handwriting does not determine the testator’s choice of the material and the tool used to write down the last will. It can be a pen and a piece of paper, as well as a chisel and a stone plate. In both cases, the will has to be recognised as valid. However, the will which is prepared in an electronic form, printed and then signed personally will be invalid. This position was also adopted by the Polish Supreme Court in its decision of 2 April 1998, case file number I CKU 16/9842. A failure to affix the last will with a date shall not entail the nullity of the legal act, provided that it does not call into question the testator’s ability to draw up the will, the content of the will or the relationship between several wills (Article 949 § 2 of the Polish Civil Code).

The second of the general last wills is the last will drawn up by a notary public in the form of a notarial deed (Article 950 of the Polish Civil Code). The notarial will is made by declaring one’s last will in the presence of the notary public who then prepares the document, reads it to the testator and hands it over for signature. The last will drawn up in this way has the status of an official act43 (Article 2 § 2 of the Act on Notaries Public of 14 February 199144).

The last of the general forms of wills provided under the Polish law is an allographic (oral) last will. The possibility and the conditions of its preparation are regulated in Article 951 of the Polish Civil Code. However, the legislator has narrowed down the scope of individuals entitled to make such a last will. This restriction, introduced by paragraph 3 of the above mentioned Article, applies to deaf or mute persons. This is an obvious exclusion on the grounds of the oral form of a disposition. Preparing a valid last will requires the involvement of more than one person, starting with the testator, through two witnesses and ending with the mayor, the district governor, the voivodship marshal, the district or municipality secretary or the head of the Registrar of Vital Statistics (in short: an official person). The procedure for making the disposition of property upon death shall involve the testator’s declaration, in the presence of two witnesses, of his last will, made orally to the official person. Once this has been done, a protocol must be drawn up. The legislator does not define the person responsible for drawing up the protocol or its form (handwriting or machine writing). Only the signatures of the persons involved in this process need to be handwritten45. The inability of the testator (e.g. handless person) to sign the protocol shall not entail the nullity of the will. This situation should be indicated in the protocol, taking into account the reason for the impossibility of affixing the signature. It is worth mentioning that the legislator did not leave to the testator full freedom in choosing witnesses to make last wills. Articles 956–957 of the Polish Civil Code contain provisions which provide for two impossibilities of being a witness: An absolute and a relative. The main task of the witness is to make every effort to ensure that, after the testator’s death, his last will is restored in an unobjectionable manner. The definition of the witness was created by the Polish Supreme Court (case file number: III CK 688/0446). «The witness of the oral last will is the person to whom the testator directs his last will, and who is present when making this statement, is aware of his or her role as a witness of the last will, is ready to fulfil this will and understands the content of the testator’s declaration». If one of the witnesses is the person who is absolutely incapable to do so (not having full legal capacity, blind, deaf, dumb, unable to read and write, not speaking the language of the testator, sentenced for false confessions), the disposition made by the testator will be invalid. In the case of relative nullity, i.e. if the witness is the person for whom the testator provided an economic benefit in the will (or other persons indicated in the act, e.g. a spouse), only the provision which provides the economic benefit to the witness is generally invalidated. The rest of the will shall remain in force. Exceptionally, the entire last will shall be deemed invalid if, without the invalid provision as a result of a relative incapacity of the witness, the testator would not have made such a last will. Therefore, the possibilities of new technologies will certainly impose the obligation to redefine the meaning of a direct presence when making the declaration of will by the testator. Accordingly, the use of a videoconference, when making an allographic last will, will require new jurisprudence in order to legally assess the condition of «a witness presence».

Special wills are distinguished from general wills by the fact that they can be drawn up only in extraordinarily cases47. The legislator allows for the possibility of drawing up the special will only if there are conditions specified by law. They are subsidiary to the general wills. However, bearing in mind that these last wills are only admissible in exceptional cases, the legislator has decided to limit the validity and effectiveness of these dispositions. The validity and effectiveness of last wills drawn up in the ordinary manner are not limited in time. In turn, such limitations are typical for special wills48. This restriction is contained in Article 955 of the Polish Civil Code. According to that provision, the disposition of property upon death shall cease to have effect six months after the cessation of the circumstances which justified its non-fulfilment, unless the testator dies before the expiry of that period. This period shall be suspended for as long as it is impossible for the testator to draw up his will in the general form.

The first, basic and most commonly used special form of the last will is an oral will provided for in Article 952 of the Polish Civil Code. The assessment of the validity of such a last will must be based on the identification of the existence of legally defined reasons justifying the fact of making the disposition in the indicated form. The basic prerequisite for an oral form of the last will is a fear of the testator’s imminent death. In its decision of 8 February 2000, case file number I CKN 408/9849, the Polish Supreme Court stated that the existence of such a concern was an independent condition for drawing up the special last will. The fear of imminent death has been defined as a condition that is difficult to recognize, and as it concerns the psychological sphere of a human being, it also requires consideration of the extent and intensity of the testator’s internal experience towards the environment. Therefore, it can be concluded that this concern cannot be judged only in an objective sense, but must also be based on the subjective feelings of the testator (the awareness that death is possible in the near future50). The second of the alternative conditions for making the oral last will is impossibility or great difficulty to make the last will in the general form. This requires clarification that this impossibility is the subjective circumstance which prevents the testator concerned from drawing up his last will in its general form at a given moment. This situation shall not be assessed in the light of whether anyone else would have been in a position to make the general will in the same situation51. If any of the conditions mentioned above applies, the testator may declare his will orally with the participation of at least three witnesses at the same time. However, the witnesses of the oral last will are subject to the same restrictions as witnesses of the allographic will.

Having in mind the above, the currently applied forms of last wills under the Polish law and the premises of their validity seem to be anachronic in the light of such technology possibilities, as – for example – the Cognitive Event-RElated Biometric REcognition (CEREBRE)52. Hence, if due to such technologies, biometric identification can be effective to a very high level (being like a person’s fingerprint), the most common handwritten form of the last will loses its functionality.

6.

Legal problems of the video last will ^

Video last will, as a form of drawing up the last will, is not regulated in the Polish law. This means that this form of will is not legally permissible under the Polish legal system. Making the will in the form of audio-video will therefore result in its invalidity. Accordingly, expressing the testator’s last will by pronouncing his declaration of intent to a sound and video recording device will not result in inheritance under a last will. As a consequence, if simultaneously there was not drafted a standard last will by this testator, his heirs will inherit under the statute (not under the last will). Consequently, an analogue or a digital record of the sound and the video which records the moment of the testator’s declaration of intent will not be regarded in the light of the Polish law as a valid last will. The computer file that has the function of the storage device that stores the testator’s declaration of intent will neither fulfil the basic criterion of a valid last will, namely the feature of a handwritten document. The proposed solutions will (perhaps) anticipate the opening of the Polish inheritance law to new technologies.

The term «video last will» is an abbreviation of thought. The full name of this form of last will should be: The last will drawn up in the audio-video form. The audio-video term itself refers to technologies, devices that enable the simultaneous recording and playback of audio and video records53.

Legal problems of the Polish inheritance law concerning the legal form of the last will, namely the form of an audio-video file of the testator’s declaration of will, should focus on the indication of legal premises of the legality of submitting declaration of will in such a form. In particular, the requirement of drawing the last will entirely in handwriting should be substituted by the requirement of «a personal activity of the testator». Accordingly, the validity of a video last will is related to additional legal problems connected to legal issues of technical registration of such a video last will. A large number of legal problems arise in the face of tailored-made apps (software developed by lawyers) that enable the registration of audio-video files with the recorded last will (disposition of property in the event of the testator’s death). The said software aims to strengthen the evidence of the standard last wills. The functions of such an application provide the possibility of not only recording the testator’s declarations of will in the form of audio-video file but also archiving all the assets of the testator, in the form of files (uploading photos of respective files)54.

Future legal regulations about video last will entail the necessity of regulating, from the legal point of view, the technical aspects of recording and storing audio-video files, despite the fact that the process of recording and storing audio-video files seems to be relatively easy. The device saves a sequence of video and sound at a suitable rate. Then the whole is processed into a binary file, which is transmitted and stored in the device’s memory (backup file)55. The whole recording is saved in one file in case of a digital recording. Accordingly, the access to the file is relatively easy, yet it requires additional legal regulations aimed at the security of storing video last wills as files containing data. However, what argues in favour of the video last will, is the fact that it is theoretically impossible to interfere in its content, which may confirm the inherent feature of integrity of the document (which is indispensable in case of the last will). On the other hand, it should be emphasized that while there are obstacles to modifying particular parts of the audio-video file, deleting the file is relatively easy. This technical problem and threats related to it have been referred to by the legislators in different jurisdictions, for example in the State of Florida, where the Electronic Wills Act was vetoed due to inadequate safeguards against threats related to storing electronic last wills56. The said threats related to the safeguards were raised even though the bill regulated only the last will similar to the allographic last will as described above, and not even video last will.

Any possible future legal regulations should not interfere into the allowed time of storing the recording by the testator. Recorded data should be stored, processed, reproduced, duplicated, copied on other media without any restrictions. The act of opening the last will made in the form of the audio-video recording should not be restricted by law for the heirs. The legal regulations should take into consideration that the recorded file containing the testator’s will shall, as a general rule, be on a medium that allows it to be opened (e.g. a DVD) or on the device in a format that allows it to be opened immediately (e.g. avi).

In view of the above, it can be confidently stated that the testator’s last will in audio-video form, as well as its use by the testator’s heirs, would be commonly used as a popular form of a last will, because it does not cause any technical difficulties. The technology that is currently available is indeed capable of guaranteeing a ready-to-use way of making last wills, such as a piece of paper and a pen57.

As proved above, the current state of the technology, as well as its widespread use, makes it possible to make wills in the form of audio-video. At this moment, however, it is necessary to divide the term «audio-video form» into more detailed forms of the video last will. At this point, a dichotomous division of the forms of the video last wills between the oral and the written forms of the will would be possible.

The video last will recording the oral form of the last will may be based on the registration of the testator at the moment of making last will orally. More precisely, it would be the recording on which the testator is placed in front of the video and audio recording equipment and orally makes dispositions of his property. This should be performed by the testator in a way that will be transparent. At the beginning of the recording, he should indicate that this is his last will, and then make a disposition. The heirs may be identified by reference to their personal data or by reference to their relationship or affinity, e.g. daughter, father-in-law. The audio-video last will may give to the testator the opportunity to indicate the heir even more clearly by showing a photograph of him on the recording. The prepared dispositions should be intelligible to the persons acquainted with the recording. It is worth noting the problem of the language spoken by the testator, including sign language. The testator may draw up his will in any language, if he understands the dispositions. Language does not have to be understood by the heirs. In this case, an interpreter can be designated to translate the testator’s last will. The situation is different for sign language, as there is no single, universal, worldwide set of manual characters for sign language communication58. However, it may be assumed that the declaration may be made by a person who is mute, by means of using sign language in the audio-video last will, if only it is possible to interpret the dispositions made and the content of the last will is indisputable.

The second type of video last will may be a video last will which registers a traditional written last will activity. Its construction may be based on the device recording the creation of a document by the testator. The entire recording may present only a mechanical operation of preparing the document, or may be supplemented by oral reading of the contents after the writing is completed.

When pursuing the considerations on the technique of drawing up the video will, it is undisputed that it would have to be drawn up by using the digital camera recording both video and audio in real time. It is worth mentioning that this may be done by the testator on his own, and the testator may as well use professionals for this purpose, i.e. an entrepreneur who prepares audio-video recordings. The second method of preparing the last will, i.e. engaging the person responsible for making, processing and saving a recording, does not seem to be controversial. On the contrary, it could be useful for elderly people, who do not necessarily have sufficient skills to freely operate modern devices. Therefore, both technical methods of preparing the last will in the form of audio-video should be legally acceptable59. However, the fact of legally sanctioning the participation of the third parties in the process of making the last will, on the one hand, violates the principle of the last will being independently drafted by the testator himself, and on the other hand, creates legal problems related to the defects of such a declaration of intent, including third party claims (the claims of the heirs) based on the compensation for the damage caused for negligent performance of the contract to make the last will. It concerns, in particular, the quality of the sound and the video and the conditions of the storage of the recorded last will.

To conclude, digitalisation of interhuman communication will certainly, sooner or later, force the civil law to provide proper regulations in the inheritance law in respect of the dispositions made with the use of new technologies. As can be seen from the above considerations, new digital forms of the last will would require such solutions that would be close to the legal provisions regulating written last wills. Moreover, it would be easier for the legislator to provide the solution allowing for the use of offline software technologies. Due to extensive mobility of the EU citizens and standardised IT technologies, there should be postulated regulatory solutions at the EU legislation level, which could introduce unanimous principles regarding e-will in the entire EU.

7.

Video last will in the legislation of European countries – a survey ^

Each country in its legislation must have a set of rules regarding inheritance law. Wishing to hear the views of practising lawyers in Europe (not only EU Member countries) a five-questionnaire survey was developed for the purposes of this article. It was supposed to illustrate the problem of e-wills in individual countries.

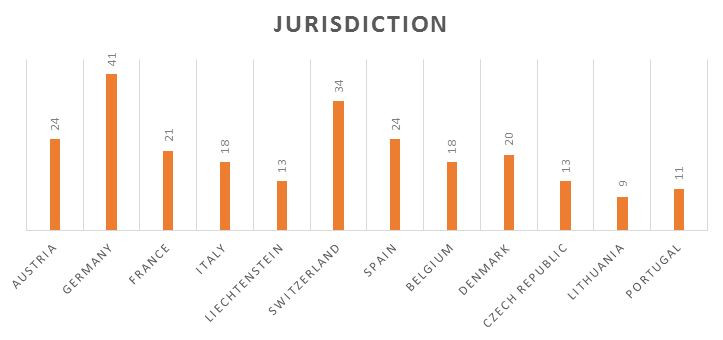

Two hundred fifty respondents from various jurisdictions participated in the survey. Their breakdown by countries is as follows:

Graphic 1: The number of respondents by country.

The first question was to illustrate the attitude of individual respondents to the use of new technologies in inheritance law, and thus whether in their opinion the legislator should create opportunities for the use of new technologies in inheritance law.

Graphic 2: The opinions about creating opportunities to use new technologies in inheritance law.

As we can see from the responses received, 65% were in favour of creating opportunities for the use of new technologies in making last wills. Only 13% are in favour of preserving current, traditional solutions.

Graphic 3: The current state of the regulation of the e-will.

The vast majority of responses indicate that the issue of e-wills is not regulated by the law and no action is taken to change this.

Another problem raised in the survey was the expected effect of allowing the legal circulation of video last will. 64% of answers indicate that such a solution could increase the popularity of wills in general, and 34% point out that it could result in increased problems with the interpretation and validity of this type of wills.

Respondents who pointed out the legal regulation of the e-will (1%) as well as those who point out the actions taken to regulate this issue (2%) come from Switzerland. Their answers were probably motivated by the federal law on electronic signatures (Bundesgesetz über Zertifizierungsdienste im Bereich der elektronischen Signatur und anderer Anwendungen digitaler Zertifikate, ZertES60) adopted on 19 December 2003. It is worth mentioning that under the Act, the legal regulations concerning electronic signatures meet the same standards as handwritten signatures. Swiss law distinguishes between three types of electronic signatures: standard, advanced and qualified. The latter, a qualified electronic signature, theoretically allows for the possibility of signing a will (although it is indicated that this document should be signed by hand)61.

Graphic 4: Possible effect of the regulation of the video form of the last will.

It was also interesting to assess whether video last will should be acceptable in all circumstances or only when there is a threat to life. According to the data collected, this form of will should be regulated rather as a specific type of will.

Graphic 5: The video form of the last will – one of the special forms of the last will or a generally accepted form?

The closest answers were found in the last question, where respondents were supposed to indicate whether they would decide to make the e-will. 62% of the respondents gave an affirmative answer.

Graphic 6: Willingness of respondents to make their last will in the form of the e-will.

To sum up the results, it can be pointed out that respondents from individual European countries indicate the need to create the possibility of making last wills in an electronic form. Hence, the general conclusion regarding the opinion on the e-will can be summarised as follows: It may be necessary to amend inheritance law, but limited only to emergency situations.

8.

The video last will in Polish law – de lege ferenda proposals based on survey ^

A similar questionnaire survey was conducted on respondents in Poland. However, it contained more questions, which were more detailed. In connection with the subject of the article, i.e. the use of new technologies in the Polish inheritance law, the answers will be used to formulate de lege ferenda proposals.

The survey involved 650 participants.

Graphic 7: The opinions about creating opportunities to use new technologies in inheritance law in Poland.

The overwhelming majority – 86% – of responses indicate the need to allow the use of new technologies in the Polish inheritance law. As a result, 86% of citizens were in favour of amendments in this matter.

In detailing the aforementioned question, respondents emphasized that the use of new technologies in inheritance law should take place primarily in a life-threatening situation of the person who prepares the will.

Graphic 8: The opinion of Polish nationals on the application of the new technologies to the inheritance law.

However, asking directly about the type of e-will that should be adopted in Polish law, i.e. whether it should be one of the general or special form of will, the views are similar. However, the answer that e-will should be one of the special wills was more emphasised.

Graphic 9: What form of last will should the e-will in Polish law take?

During the survey, respondents also expressed their opinion as to which technical form of preparing e-will should be regulated.

Graphic 10: The form of e-will in Poland should be as follows.

The overwhelming majority indicated that if the e-will is regulated, it should take the recording-video form of the last will. This is justified by the fact that the access to the video and audio recording equipment is more widespread and cheaper than obtaining a secure electronic signature. The simplicity of preparing the last will in the audio-video form also argues in favour of the recording.

Similarly to European respondents, Polish citizens also highlighted that the legal regulation of e-wills may contribute to the increased popularity of wills in general.

Graphic 11: Possible effect of regulating the video form of the last will in Poland.

The Polish people were also asked whether they would be willing to use this form of will if it was to be regulated.

Graphic 12: Willingness of Polish respondents to make their last will in the form of the e-will.

81% of respondents indicated that they would make their will in electronic form, 35% of which indicated that they would make their will in this form only in a life threatening situation

The storage of the contents of e-will was also an important issue in the questionnaire.

Graphic 13: The opinion about the storage of the prepared e-wills.

In this respect, the opinions of the Poles are divided. However, they have highlighted more secure forms of storage for the last wills than leaving the latter at home on a data medium.

In summary, the following results should be indicated:

- The Polish people express their interest in the use of new technologies in the inheritance law,

- The legally-regulated e-will would be met with interest on the part of citizens,

- The e-will should take the form of video last will,

- The availability of this form of last will could be limited only to special life-threatening situations,

- The special online register should be set up or a notary public should be responsible for storing last wills.

9.

E-will – legislative challenges ^

Legal loopholes and the lack of regulation of e-wills in the particular legal systems make it necessary for the validity of a disposition of property upon death which has been made electronically to be subject to judicial review on a case-by-case basis. An analysis of international case law shows that cases related to the validity of e-wills have been on the court’s agenda for many years. The number of similar cases will increase from year to year. This, combined with the lack of comprehensive regulation in this area, may result in the increase in the costs of succession proceedings, as well as an excessive burden on the courts. As a result, matters related to inheritance law and legal transactions in this area may get bogged down in long trials focusing on assessing the validity of e-wills, during which individual parties will try to prove their claims by accusing the legislator of the mismatch between the current form of regulation and the ongoing process of digitisation.

The results of the survey indicate a clear interest on the part of the public, both in Poland and in selected European countries, in the amendment of traditional wills. Based on the results obtained, it can be argued that inheritance law should not be a closed matter to the technological development of the economy. Based on the widespread availability and use of technological devices, respondents explicitly expressed their interest in the possibility of making wills in electronic form. Moreover, they also pointed out that such solutions would contribute to the increase of popularity of inheritance under a will, which is less complicated than statutory inheritance.

In view of the above, it seems necessary to postulate amendments to the inheritance law of individual states. Based on the opinions expressed by respondents, it will become increasingly necessary over time to allow wills to be made in electronic form: An electronic document, in the audio-video format.

Therefore, it is possible to point out the necessity of regulating the issue of e-will on the EU level. By specifically referring to the types of Union legislation, a Regulation is the instrument that would best contribute to the unification of legal solutions in all Member States. In conclusion, the issue of e-wills may be one of the upcoming challenges for the European legislature.

10.

Conclusions ^

The article was based on the discussion of the issue of the e-will limited to considerations on the hypothetical, future shape of the video last will. Taking into account the characteristics of the present solutions, which concern wills and which are regulated by Polish law, considerations on future regulations, conditions, the form of video last will and the conducted surveys, many courageous conclusions and hypotheses can be formulated.

First of all, conducted considerations indicated that the Polish inheritance law, as compared to other areas of law, has not been significantly amended in terms of opening up to new technologies. The omnipresence of technological devices in day-to-day life, as well as the research obtained results highlighting the interest of citizens in the use of technological devices during the preparation of their last will, create the opportunity for changes and amendments in this matter.

Furthermore, both surveys indicate the favourable attitude of respondents towards preparing last wills in electronic form in the future. They emphasize that this form of will can increase the popularity of wills in general, and that it will be safer and simpler for heirs to interpretation.

The opinions are divided on whether the e-will should be one of the ordinary forms of a will or whether it should be a special one, drawn up in a life-threatening situation. The statistics point to a stronger emphasis on the second possibility. It is therefore possible to postulate that the regulated e-will should be a special form of the last will. Over time, it may be considered whether or not to transfer it to the category of ordinary wills.

Both national legislators and the EU legislator may soon be forced to meet the challenges of technological development and adapt the existing legal norms, including those emphasized in this study of inheritance law, to the current economic reality.

Małgorzata Kiełtyka, Attorney, Founding Partner of KG LEGAL Law Firm, specialises in cross border cases, corporate law, life science and new technologies.

Paweł Dyrduł, Associate in KG LEGAL Law Firm, interested mainly in commercial law, banking law, corporate law and broadly understood civil law.

- 1 A. Olejniczak, J. Haberko, A. Pyrzyńska, D. Sokołowska (eds.), Współczesne problemy prawa zobowiązań, Wolters Kluwer Poland, Warsaw 2015.

- 2 Jan Christian Seevogel, Facebook und Recht, Köln 2014.

- 3 What Is an «Electronic Will»?, Harvard Law Review, https://harvardlawreview.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/1790-1811_Online.pdf.

- 4 Ibidem

- 5 http://www.uniformlaws.org/shared/docs/electronic%20wills/2017oct_E-Wills_Proposed%20E-Wills%20Bills%20and%20Nevada%20Statute_2017oct1_REVISED.pdf.

- 6 https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sylvia_Papadopoulos/publication/325574902_Electronic_Wills_with_an_Aura_of_Authenticity_Van_der_Merwe_v_Master_of_the_High_Court_and_Another/links/5b168add4585151f91fb922b/Electronic-Wills-with-an-Aura-of-Authenticity-Van-der-Merwe-v-Master-of-the-High-Court-and-Another.pdf?origin=publication_detail.

- 7 http://sas-space.sas.ac.uk/5406/1/1925-2713-1-SM.pdf.

- 8 https://www.caselaw.nsw.gov.au/decision/54a637ad3004de94513d9a45.

- 9 https://www.sssb-law.com/media/1297/kylebgee_pl-journal-mar-apr-2016_final.pdf.

- 10 https://archive.sclqld.org.au/qjudgment/2013/QSC13-322.pdf.

- 11 https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/2016-03-22/act-1981-069.

- 12 https://archive.sclqld.org.au/qjudgment/2017/QSC17-220.pdf.

- 13 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018.

- 14 K. Osajda, Ustanowienie spadkobiercy w testamencie w systemach prawnych Common Law i Civil Law, CH BECK, 2009.

- 15 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018.

- 16 https://www.studiocataldi.it/codicecivile/codice-civile.pdf access on 23/07/2018.

- 17 Own translation.

- 18 Journal of Laws of 2018, item 1025.

- 19 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz., CH BECK, 2018.

- 20 E. Gniewek, P.Machnikowski (eds.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2017.

- 21 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz., CH BECK, 2018.

- 22 M. Gutowski, Kodeks Cywilny. Tom II. Komentarz. Art. 450-1088, CH BECK, 2016.

- 23 J. Gwiazdomorski, Wykładnia przepisów o testamencie na tle uchwały składu siedmiu sędziów Sądu Najwyższego, NP 1973, Nr 6, pp. 828–830.

- 24 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2018.

- 25 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2018.

- 26 B. Kordasiewicz (ed.), Prawo spadkowe. System Prawa Prywatnego. Tom 10, CH BECK, 2015.

- 27 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018.

- 28 B. Kordasiewicz (ed.), Prawo spadkowe. System Prawa Prywatnego. Tom 10, CH BECK, 2015.

- 29 Journal of Laws of 2018, item 1360.

- 30 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2018.

- 31 Ibidem.

- 32 Access Legalis on 24/07/2018.

- 33 B. Kordasiewicz (ed.), Prawo spadkowe. System Prawa Prywatnego. Tom 10, CH BECK, 2015.

- 34 J. Wierciński, Brak świadomości albo swobody przy sporządzaniu testamentu, LexisNexis, 2010.

- 35 M. Gutowski (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Tom II. Komentarz. Art. 450-1088. CH BECK, 2016.

- 36 Z. Radwański (ed.), Prawo cywilne – część ogólna. System Prawa Prywatnego tom 2, CH BECK, 2008.

- 37 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2018.

- 38 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018.

- 39 M. Gutowski (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz. Art. 1-449, CH BECK, 2016.

- 40 B. Kordasiewicz (ed.), Prawo spadkowe. System Prawa Prywatnego. Tom 10, CH BECK, 2015.

- 41 Also: E. Skowrońska-Bocian, Komentarz do Kodeksu cywilnego. Księga czwarta. Spadki, LexisNexis, 2011.

- 42 Access to Legalis on 24/07/2018.

- 43 E. Gniewek, P.Machnikowski (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2017.

- 44 Journal of Laws of 2017, item 2291.

- 45 E. Gniewek, P. Machnikowski (eds.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2017.

- 46 Access to Legalis on 24/07/2018.

- 47 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018.

- 48 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2018.

- 49 Access to Legalis on 24/07/2018.

- 50 The Supreme Court in its decision of 15 February 2008 I CSK 381/07, access to Legalis on 24/07/2018.

- 51 K. Osajda (ed.), Kodeks cywilny. Komentarz, CH BECK, 2018.

- 52 https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/7435286/, access on 14 August 2018.

- 53 J. Barta, R. Markiewicz, Prawo autorskie, Wolters Kluwer Polska, 2016.

- 54 http://www.videotestaments.com/.

- 55 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018

- 56 https://www.wealthmanagement.com/estate-planning/florida-governor-vetoes-electronic-wills-act.

- 57 W. Załucki, Videotestament. Prawo spadkowe wobec nowych technologii, CH BECK, 2018.

- 58 Ibidem

- 59 Ibidem

- 60 https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20131913/201701010000/943.03.pdf.

- 61 https://www.pandadoc.com/electronic-signature-law/switzerland/.