1.

Introduction ^

2.

E-Participation ^

The rise of social media and web 2.0 facilitated new forms of interaction and collaboration of citizens with governments collectively labelled as e-participation. While general elections in democracies are part of the participatory decision-making [Krimmer 2002], this paper refers to the term e-participation as applied by Macintosh [2004] who contrasts the new technological opportunities for the inclusion of citizens in the decision-making process within a deliberative democracy with the digital transformation of elections as in e-voting. Thus, e-participation comprises variations of citizen engagement and can be categorized in different schemas.

2.1.

Success Factors ^

2.2.

Evaluation ^

2.3.

Frameworks and criteria ^

2.4.

The problem of ex post evaluation ^

Kubicek/Aichholzer [2016] describe an «evaluation gap» when they state that the research for standard evaluation frameworks will not bring the desired results of general applicability. They claim that different criteria and methods for evaluation must be applied depending on the specific participation initiative and different groups of actors. Despite the increasing literature on evaluation frameworks in the domain of e-participation there is no widely accepted model. The same e-participation tool can be useful and successful in one context and be the source of failure in another. Thus, Kubicek/Aichholzer [2016] propose earlier involvement of stakeholder groups prior to the evaluation as opposed to ex post involvement and define at least five stakeholder groups: decision makers; organizers; users/participants; target groups/people concerned; and the general public. Kubicek/Aichholzer [2016] call it an actor-related approach set up like a field experiment.

2.5.

Methods for evaluation ^

2.6.

The evaluators ^

3.

Methodological approach of this paper ^

3.1.

Process for creating custom-made evaluation management ^

The process consists of three basic steps, each divided into subitems: expectation analysis; creation of the evaluation instrument; conduction of the evaluation.

- Expectation analysis: Structured inquiry into the expectations of the organisers in charge of the participation process, such as public agencies or project leaders. (In research projects, the expectation analysis is often based on the work plan.)

- Definition of rationale and objectives: The inquiries of rationale and objectives should be conducted by a domain expert who provides additional expertise and an outside perspective, to determine primary and possibly secondary objectives of the participation process. This can be done in interviews with the project organisers or in a discussion setting with stakeholders.

- Definition of expected outcomes and success: Following the definition of the rationale and objectives, the expectations of the organisers/stakeholders should be collaboratively defined. The expert can relate the definition of success to experiences from other e-participation projects and together with the organisers reflect on the truly relevant and realistic outcomes of the project.

- Creation of the evaluation instrument: Structuring and defining the evaluation process based on the expectation analysis. This should be done by an expert with support from the organisers or managers of the respective e-participation project.

- Definition of the criteria that shall be analysed: What shall be evaluated?

- Definition of indicators to analyse the criteria: What shall be measured?

- Definition of the methods or tools used to measure the indicators: How shall it be measured?

- Definition of success values: When can a measured value be defined as success or failure?

- Definition of the measuring time: When is the appropriate time to measure?

- Conduction of the evaluation: The execution of the evaluation tasks according to the evaluation instrument.

- The actual evaluation takes place simultaneously with project execution and thereafter. Feedback loops for instant improvements of the e-participation process can be defined in the evaluation instrument if adequate measurement takes place during project execution.

- After all tasks defined in the evaluation instrument are completed, a final evaluation report can be produced. This might take considerable time after the end of the e-participation process if impact criteria are to be evaluated. In such cases interim evaluation reports are recommended.

3.2.

Example ^

The following example in table 1 visualises how the evaluation instrument could be structured by referring to basic evaluation criteria in e-participation. For instance, participation rate: In step one of the process (the expectation analysis) the fictional organisers of an e-participation project state that a sufficient number of registered and active users is of great relevance to them and they consider 50 active users per participation stage and a minimum of 100 registered users overall as a success. Thus, the evaluation instrument for this specific item could be set up as the first row in the following table.

| Criteria | Indicators | Method/Tool | Success values | Measuring time |

| Participation rate | Number of active users | Platform data | > 50 active users per stage | End of each e-participation stage |

| Number of registered users | Platform data | > 100 registered users | End of e-participation execution | |

| Platform design | Helpdesk support requests | Number of support requests submitted to helpdesk | < 2 per 50 users | Each week |

| Quality of the users’ ideas | Ideas are realisable | Assessment from expert | At least 5 positively assessed ideas | 1 month after end of e-participation |

| Implementation of results | Inclusion of aspects of the best users’ ideas | Interview with selected users | Positive assessment by users | 1 year after end of e-participation |

Table 1: Example of an evaluation instrument

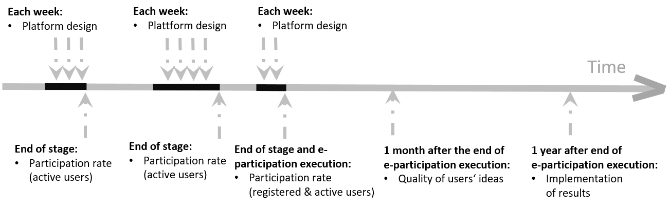

Looking at other the evaluation criteria in table 1 (platform design, quality of the users’ ideas, and implementation of the results) shows the practicability of the process modelled to create a suitable evaluation instrument that can be adapted to the needs of individual projects with the integration of different evaluation methods. Some criteria can be more complexly measured with several indicators and indicators can also be measured with several methods or tools. The examples in table 1 are kept simple to avoid the need of explaining a context. It is crucial to remember that all the information placed in the table of the evaluation instrument originates from a thorough expectation analysis conducted by an expert together with the (here fictional) organisers/initiators of the e-participation project. Figure 1 shows the exemplary e-participation process with 3 stages. All evaluation elements from the example in table 1 have been integrated in the timeline below.

4.

Conclusion ^

5.

References ^

Aichholzer, Georg/Westholm, Hilmar, Evaluating eParticipation projects: practical examples and outline of an evaluation framework. European Journal of ePractice,7(3), 2009, pp. 1–18.

ECAS (European Citizen Action Service), The European Citizens’ Initiative Registration: Falling at the first hurdle? http://www.ecas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/ECI-report_ECAS-2014_1.pdf (accessed 10 August 2017), 2014.

Edelmann, Noella/Höchtl, Johann/Sachs, Michael, Collaboration for Open Innovation Processes in Public Administrations. In: Charalabidis, Yannis/Koussouris, Sotirios (Eds.), Empowering Open and Collaborative Governance. Springer, Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 21–37, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27219-6_2.

Forss, Kim, An Evaluation Framework for Information, Consultation, and Public Participation. In. Evaluating public participation in policy making, OECD Publications, 2005, pp. 41–82, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264008960-en.

Gibson, J. Paul/Krimmer, Robert/Teague, Vanessa/Pomares, Julia, A review of E-voting: the past, present and future In Annals of Telecommunications 71/7-8, 2016, pp. 279–286, DOI 10.1007/s12243-016-0525-8.

Große, Katharina, E-participation – the Swiss army knife of politics? In: CeDEM13: Conference for E-Democracy an Open Government, MV-Verlag, 2013, pp. 45–59.

Heussler, Vinzenz/Said, Giti/Sachs, Michael/Schossböck, Judith, Multimodale Evaluierung von Beteiligungsplattformen. In: Leitner, Maria (Ed.) Digitale Bürgerbeteiligung, Springer, Forthcoming 2018.

Janssen, Marijn/Helbig, Natalie, Innovating and changing the policy-cycle: Policy-makers be prepared! In: Government Information Quarterly, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2015.11.009.

Krenjova, Jelizaveta/Raudla, Ringa, Participatory Budgeting at the Local Level: Challenges and Opportunities for New Democracies. In: Halduskultuur – Administrative Culture 14 (1), 2013, pp. 18–46.

Krimmer, Robert, Internet Voting: Elections in the (European) Cloud. In: CeDEM Asia 2016: Proceedings of the International Conference for E-Democracy and Open Government, Asia 2016, Deagu, Edition Donau-Universität Krems, 2016, pp.123–125.

Krimmer, Robert, E-Voting.at: Elektronische Demokratie am Beispiel der österreichischen Hochschülerschaftswahlen. Working Papers on Information Processing and Information Management, 05/2002.

Krimmer, Robert/Volkamer, Melanie, Observing Threats to Voter’s Anonymity: Election Observation of Electronic Voting. In: Working Paper Series on Electronic Voting and Participation, 01/2006, pp. 3–13.

Kubicek, Herbert/Aichholzer, Georg, Closing the evaluation gap in e-Participation research and practice. In: Aichholzer Georg/Kubicek Herbert/ Torres, Lourdes (Eds.) Evaluating e-Participation, Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp. 11–45.

Kubicek, Herbert/Lippa, Barbara/Koop, Alexander, Erfolgreich beteiligt. Nutzen und Erfolgsfaktoren internetgestützter Bürgerbeteiligung – Eine empirische Analyse von zwölf Fallbeispielen. Gütersloh, Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2011.

Loukis, Euripidis/Xenakis, Alesandros/Charalabidis, Yannis, An evaluation framework for e-participation in parliaments. In: International Journal of Electronic Governance, 3(1), 2010, pp. 25–47.

Macintosh, Ann, Characterizing e-participation in policy-making. In: System Sciences, 2004. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Hawaii International Conference on. IEEE, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.98.6150&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 21 October 2017), 2004.

Macintosh, Ann/Whyte, Angus, Towards an evaluation framework for eParticipation. In: Transforming government: People, process and policy, 2(1), 2008, pp. 16–30.

Ministers eGovernment, Ministerial Declaration on eGovernment. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/sites/digital-agenda/files/ministerial-declaration-on-egovernment-malmo.pdf (accessed 30 October 2017), 2009.

Müller, Philipp, Offene Staatskunst. In: Internet und Gesellschaft Co:llaboratory: Offene Staatskunst. Bessere Politik durch Open Government, https://www.open3.at/wp-content/uploads/IGCollaboratoryAbschlussbericht2OffeneStaatskunstOkt2010.pdf (accessed 20 September 2017), 2010, pp. 11–27.

OECD. Evaluating Public Participation in Policy Making. OECD Publications, 2005, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264008960-en.

Panopoulou, Eleni/Tambouris, Efthimios/Tarabanis, Konstantinos, Success factors in designing eParticipation initiatives. In: Information and Organization, 24(4), 2014, pp. 195–213.

Parycek, Peter et al., Positionspapier zu E-Democracy und E-Participation in Österreich. https://www.ref.gv.at/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/EDEM-1-0-0-20080525.pdf (accessed 29 October 2010) 2008.

Parycek, Peter/Hochtl, Johann/Ginner, Michael, Open government data implementation evaluation. In: Journal of theoretical and applied electronic commerce research, 9(2), 2014, pp. 80–99.

Parycek, Peter/Sachs, Michael/Sedy, Florian/Schossböck, Judith, Evaluation of an e-participation project: Lessons learned and success factors from a cross-cultural perspective. In: International Conference on Electronic Participation. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014, pp. 128–140.

Prosser, Alexander, eParticipation – Did We Deliver What We Promised? In: Advancing Democracy, Government and Governance, 2012, pp. 10–18, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-32701-8_2.

Scherer, Sabrina/Wimmer, Maria A., A regional model for E-Participation in the EU: evaluation and lessons learned from VoicE. In: International Conference on Electronic Participation. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010, pp. 162–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-15158-3_14.

Schossböck, Judith/Rinnerbauer, Bettina/Sachs, Michael/Wenda, Gregor/Parycek, Peter, Identification in e-participation: a multi-dimensional model. In: International Journal of Electronic Governance, 8(4), 2016, pp. 335–355, https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEG.2016.082679.

The White House, Memorandum for the Heads of executive Departments and Agencies. Transparency and Open Government. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/transparency-and-open-government (accessed 30 October 2017) 2009.

Toots, Maarja/Kalvet, Tarmo/Krimmer, Robert, Success in eVoting–Success in eDemocracy? The Estonian Paradox. In: International Conference on Electronic Participation. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2016 pp. 55–66 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-45074-2_5.

Toots, Maarja/McBride, Keegan/Kalvet, Tarmo/Krimmer, Robert, Open data as enabler of public service cocreation: exploring the drivers and barriers. In CeDEM 2017 Conference. 2017, IEEE, pp. 102–112, https://doi.org/10.1109/CeDEM.2017.12.

Wimmer, Maria A., Ontology for an e-participation virtual resource centre. In: Proceedings of the 1st international conference on Theory and practice of electronic governance. ACM, 2007, pp. 89–98. ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/1328057.1328079.