1.

Introduction ^

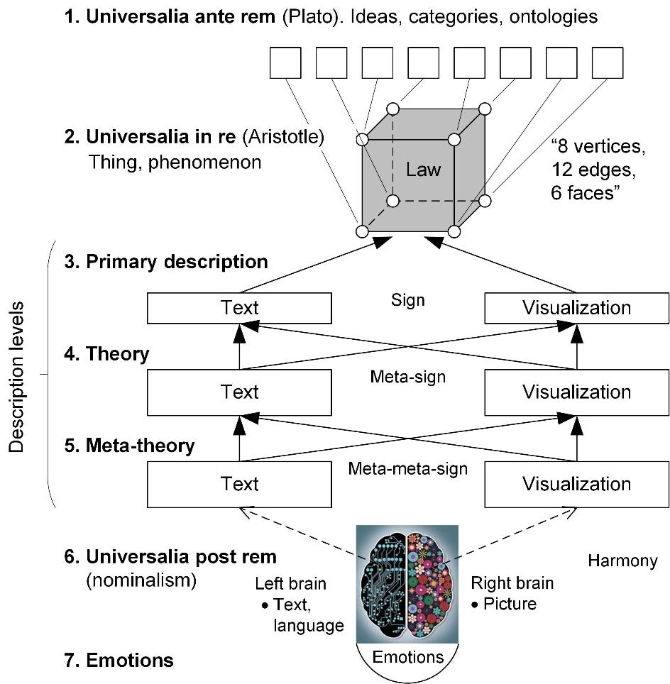

Volker Boehme-Neßler (2011) writes about the «visualisification of the law» and its multiple facets, including the medium of television. He notes the complementarity of text and image and the different characteristics and functions [Boehme-Neßler 2011, 86 ff]. Techno-images such as «structures, relationships or dynamic processes are often understood more readily when presented as maps, diagrams models, building plans or computer simulations». A reason for this is that they «are created by causal mechanisms» (ibid., p. 56–57). However, the latter are not prevalent in law.

2.

A General Schema for Visualization ^

3.

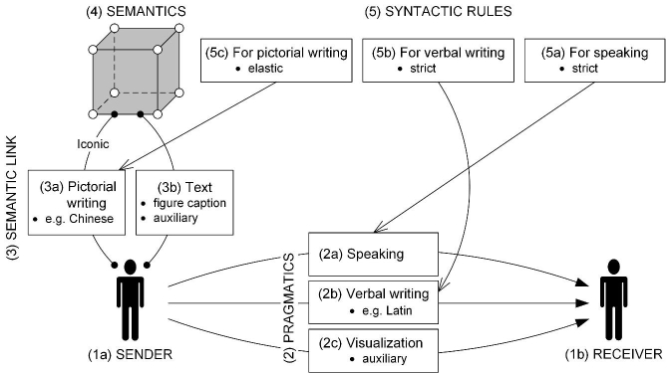

Differences between Verbal Writing and Pictorial Writing ^

This section compares verbal writing and pictorial writing in human communication. Verbal writing has its roots in the Latin language. Examples of pictorial writing are Chinese characters and the icons in public airports or in Olympic game arenas. The theme Colorizing Chinese Characters is initiated by Lachmayer and Weng.1

4.

Examples of Legal Visualizations ^

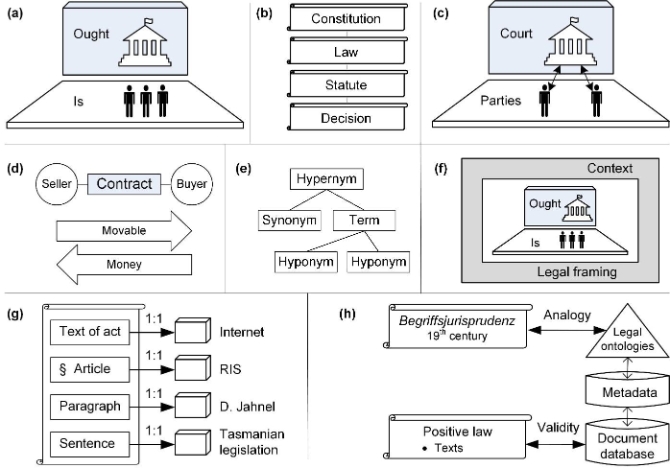

Figure 3: Examples of visualizations: a) legal stage, b) hierarchy of legal sources, c) trial as a ping-pong process with a court, d) legal institution such as a sales contract, e) thesaurus/ontology, f) legal framing, g) granularity entities, h) analogy of methods in Begriffsjurisprudenz and legal ontologies

5.

Term «Situational Visualization» in Computing ^

6.

Situation versus Case ^

Situations and cases are characterised differently:

- Type. A situation constitutes a generic behaviour pattern, whereas a case – a concrete one.

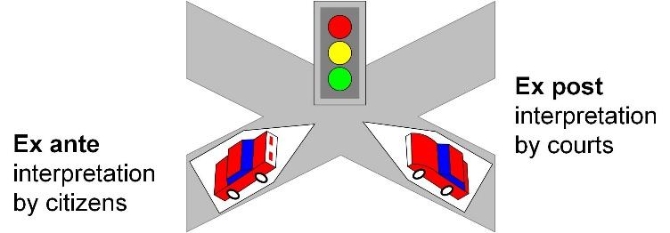

- Ex-ante/ex-post. A situation is related with ex-ante analysis, whereas a case – with ex-post.

- Time. A situation concerns the future, whereas a case – the past.

- Alternatives. In a situation, alternatives are possible, and this is essential. There are no alternatives in a case. A concrete past behaviour is concerned. However, alternatives can appear in hypothetical evaluations, such as «Should the actors perform another manoeuvre, the accident would not happen.»

- Language. Situations have no language at all.

- A situation is mentally – visually, acoustically, sensibly – interpreted. Suppose a driver is in a crossroad. A mental language is non-textual and non-professional. Sensual (visual, aural, etc.) comprehension dominates, and textual descriptions appear on the periphery. Hence, a situational language is non-professional. A communication language does not need to be textual; cf. gestures. Therefore, a situational language is loosened and differs from case languages.

- Roles are inherent in situations, e.g. «pedestrian» or «driver». The actors» legal status may be implicit because rights and obligations are comprised by their roles.

- Artificial agents can use formal languages. As an example, suppose multi-agent systems. The agents» beliefs, desires and intentions are represented in computers

- Cases are explicitly formulated in documents. Quod non est in actis, non est in mundo – «What is not in the documents does not exist». Cases are textually available. The major facts are described in an investigation report. However, statements about facts can be defeated during the argumentation in the litigation. Visual descriptions such as schemes are supplementary and appear on the periphery.

- There are two kinds of languages: first, the non-professional language of witnesses and, second, the professional juristic language. Legal subsumption serves as a bridge.

- Placing onto the Is and Ought stages

Situation- Situations are assigned to Is. A situation is always real and factual. As an example, suppose a crossroad with the red light on. You would like to cross, but do not want to show your children a bad example, as they learn the customary law from your behaviour.

- In contrast, the type of a situation is assigned to Ought. A situation type allows visual representations such as a schema. This appears in technical devices.

- Cases are also assigned to Is. Every case has passed. The reference range is not important. A case is fixed in the text.

- A case is on the Is stage but can be viewed from two perspectives. First, the case is assigned to the subjective law. Secondly, the case is assigned to a legal proceeding, and hence, to the objective law. Here, argumentation arises. The players are assigned roles in the legal proceeding such as plaintiff, defendant, witness, expert, etc.

- Web applications. e-Government application examples in Austria:

For situations, see www.help.gv.at. For cases, see www.ris.bka.gv.at. - Legal instruments. Distinct legal instruments are concerned:

Situation: (i) the roles of actors; (ii) assumptions (hypothetical facts); (iii) rules which govern the situation; (iv) additional regulations which govern the situation.

Case: (i) claim; (ii) evidence; (iii) attacks; (iv) litigation can consist of several cases (e.g. criminal and civil). - Formalisms. Distinct legal instruments are concerned:

Situation: deontic logic, abstract normative systems, etc.

Case: case modelling approaches, factors, etc. - Customary law, machine law and statutory law

Situation: customary law and machine law are in the foreground. As an example, suppose a zebra crossing. Pedestrians aim to cross it. Statutory law (the road rules) regulates this situation. However, ordinary people are governed primarily by the customary law which is superimposed. And finally, the situation is governed by traffic lights – machine law steps in.

Cases: the traditional hierarchies of legal sources prevail.

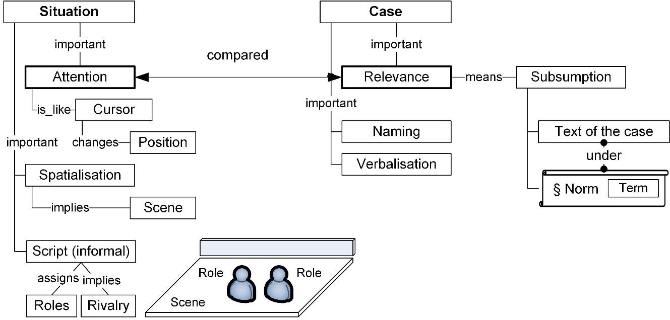

- Situation. Here, attention is the most important element. Attention can be compared to a cursor that can move to different positions. The players reside similarly as on a stage and create scenes like people around a table. A script assigns the players their roles.

- Case. Here, legal subsumption, i.e. bringing the text under norms, is in the forefront. It is important that the case elements are relevant to the norms. The elements of the issue have to be named in a professional legal language. Cases are marked by verbalisations. Here, the relationships – references – of the text to the relevant norms are addressed.

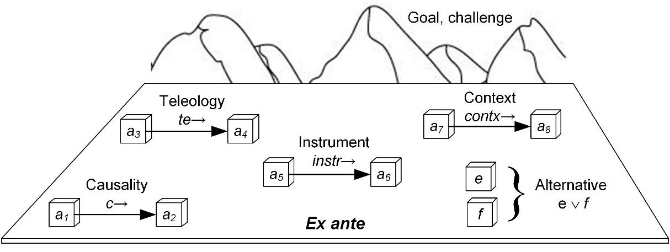

- Situational elements. These elements are the constituents of the situation. They are denoted by small letters, e.g. a, b, c, driver, pedestrian, etc. They exist in time and space.

- Relations. These are the relations between the situational elements. There are many kinds of relations: causal (c→), teleological (te→), instrumental (instr→), contextual (contx→), etc. These relations are comprised by both legal relations such as debt, but also by empirical non-legal relations. The relations represent different perspectives.

7.

Conclusions ^

8.

References ^

Boehme-Neßler, Volker, Pictorial Law: Modern Law and the Power of Pictures, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, 2011.

Boehme-Neßler, Volker, Die Macht der Algorithmen und die Ohnmacht des Rechts, Neue Juristische Wochenschrift, volume 42, 2017, pp. 3031–3037.

Čyras, Vytautas / Lachmayer, Friedrich, Situation versus Case and Two Kinds of Legal Subsumption. In: Schweighofer, Erich / Kummer, Franz / Hötzendorfer, Walter (Eds.), Abstraction and Application, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2013, books@ocg.at, Vienna 2013, pp. 347–354.

Čyras, Vytautas / Lachmayer, Friedrich / Lapin, Kristina, Structural Legal Visualization, Informatica, volume 26, issue 2, 2015, pp. 199–219. http://www.mii.lt/informatica/pdf/INFO1059.pdf.

Endsley, Mica R., Situation Awareness Global Assessment Technique (SAGAT). In: Proceedings of the IEEE 1988 National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, volume 3, pp. 789–795. http://www.ieeeexplore.ws/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=195097.

Krum, David M. / Ribarsky, William / Shaw, Christopfer D. / Hodges, Larry F. / Faust, Nickolas, Situational awareness. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Virtual Reality, 2001, pp. 143–150.

Lachmayer, Friedrich / Hoffmann, Harald, From legal categories towards legal ontologies. In: Lehmann, Jos / Biasiotti, Maria Angela / Francesconi, Enrico / Sagri, Maria Teresa (Eds.), LOAIT – Legal Ontologies and Artificial Intelligence Techniques, volume 4 of the IAAIL Workshop Series, Wolf Legal Publishers, Nijmegen 2005, pp. 63–69.

Röhl, Klaus F. / Ulbrich, Stefan, Recht anschaulich. Visualisierung in der Juristenausbildung, Halem, Köln 2007.

Schoormann, Thorsten / Hofer, Julien / Behrens, Dennis / Knackstedt, Ralf, Rechtsvisualisierung in 20 Jahren IRIS – eine multimethodische Literaturanalyse. In: Schweighofer, Erich / Kummer, Franz / Hötzendorfer, Walter / Sorge, Christoph (Eds.), Trends and Communities of Legal Informatics. Proceedings of the 20th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2017, books@ocg.at, Vienna 2017, pp. 369–376.

- 1 F. Lachmayer, in cooperation with C. Walser Kessel and Y.-H. Weng, Resemantisierung der Syntax. Kolorisierung chinesischer Schriftzeichen. A presentation at the Weblaw event, 16.03.2016, Museum Rietberg, Zurich, cf. http://www.legalvisualization.com/media/Rechtsvisualisierung_20160316_Z%C3%BCrich-Kolorisieren-chinesischer-Schriftzeichen.pdf and https://jusletter-it.weblaw.ch/visualisierung/ColChinC.html (all Websites lastly accessed on 17 January 2018).