The Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME) was commissioned by the Hungarian State Treasury of a preliminary and theoretical research. The assignment was about consistency testing and exploring the possibilities of automatization (algorithmization) of specific administrative processes. The process under investigation is that of the state family support related to the Family Support Act (Family Support Act 84/1998) and other lower-level regulations. To investigate the consistency and coherence of the selected act we extracted all essential concepts from the text and built a formal ontology, however a detailed account of those results won’t be exposed here. What we present here is some theses about the possibilities of automatization in legal-administrative processes.

From an administrative point of view, the given legal text can be interpreted as a set of criteria for a decision-making process. The Family Support Act describes the conditions under which the different types of support may be granted to eligible persons. Whether or not an individual is in receipt of a benefit is a result of an administrative process. In such a process, an application must be submitted, the eligibility of the individual is assigned after considering whether the conditions required by law are met, or after requesting further information from the applicant or authorities. The agent who decides on the acceptance of the application, the individual assessment of the eligibility status and any further requests for information, is an authorized representative on behalf of the authority. The whole process consists of a large number of decisions based on millions of unique, particular data. These decisions can be interpreted as individuating or instantiating acts based on the general, legal conditions provided by the given Act on the one hand, and on the individual data about the potentially eligible people on the other hand. The legislator defines a legal status in the law (for example, «school-age child»), and later in the administrative procedure, administrators decide case-by-case whether a given child meets the requirements of the status. The legislator constitutes, in a Searlean sense (Searle, 1995), a legal status («the school-age child counts as...») and the decision-makers determine, in all individual cases, whether a particular child can be interpreted as an instance of the given legal status. If a child meets the criteria, the administrator establishes an individual social fact («Anna counts as a school-age child»). There are two types of «counts as» statement: one general or universal claim (when the legislator constitutes a general legal status), and one individual or particular claim (when an administrator decides that the individual case meets the criteria defined in the universal term).

In general, the legal-administrative procedure can be interpreted as a continuous decision-making process on individual cases based on particular data. The crucial questions are from what source and how decision-makers obtain those data, and how the data can be typified.

By process description, we mean identifying and linking the decision points of all possible individual family support cases. The complete description is a graph consisting of nodes that represent millions of data processing actions. Some of the nodes are decisions in an ordinary, administrative sense, some of them can be interpreted as automatic decisions, lastly there are decisions which are partly supported by the machine but require human interventions as well. In the default case, a person who is eligible for the family allowance will first apply for the support. Her eligibility status will be confirmed. Then, after gathering additional information, there will be decided which category of eligibility applies to the specific case. The given amount of monetary support will be transferred monthly for the person eligible until the end of the eligible status. Because more than one person may be eligible concerning a child (parents, grandparents, correctional institution director), and the allowance can be shared, and other factors may influence the disbursement (such as the number of missed school days), the graph is quite complicated.

We start with the distinction of two types of facts (Searle, 1995), natural (or brute) facts and social facts (or construction) on the basis that the former are, in essence, independent of human will, while the latter are constructed by human will. Of course, a natural fact can be influenced by human action (will), but this fact can occur even if we eliminate human will from the causal chain. If someone deliberately knocks a vase from the table, it falls to the ground. In this case, the human will is the cause of the event, but if we subtract human will from this causal chain, the event may still happen (a cat knocks or the wind blows it off). Conversely, if a mother declares that she wants to name her child John, this manifestation of will is a necessary condition for the fact to come into being, and if we eliminate that will from the process, the fact itself cannot be realized.

Our first, a little bit surprising, finding was that, despite the important distinction between the two types of facts, within the legal-administrative procedure all relevant information are interpreted as legal fact – as a subtype of social fact (Morawski, 1999). The birth of a child is a brute fact, but it will only be taken into account in the legal-administrative process if it is registered, i.e. it is construed as a legal fact. The important question is how and from where these legal facts can be obtained. From the text of a given act, the information needs of the decision-makers can be extracted, but it is necessary to classify the data that decision-makers need on the one hand, and the channels through which the data arrive must be explored and classified on the other hand.

The most important data (personal, marriage, estate records, etc.) has been stored into state records (i.e. state administration records systems) in the last decades, but these types of governmental databases do not contain all information that is needed in the legal-administrative process.

In the current administrative practice, the concept of records may be interpreted too narrowly. Roughly speaking, state records mean official, authentic state records. If we wanted to describe all the information required in the whole process, we would need to extend our focus and expand the meaning of the record. The term «registry» will be used in this expanded sense. By «registry» we refer to all information sources that provide any type of data for the decision process.

Official state records systems are specialized registries (in Hungary, the government decree on ensuring the processing of state records belonging to the national data assets (Government Decree 38/2011) classifies 32 state records as national data assets). However, there exist other types of registries in the decision process studied. In some cases, within the process under investigation, the decision-makers need some professional data (medical statement and certification on a child’s chronic illness or official school report on a child’s persistent absence from school), which are not stored in official state records. In the current legal-administrative practice, these types of data are not interpreted as data coming from state records (an official registry), even though they are treated in the same way and often with the same weight during the decision process. Finally, among the information needs of the governmental decision-makers, there are personal statements or declaration that can only be obtained from citizens who are involved in the cases (for example statements on the divorce of parents, moving, or bank account change).

Thus, the information needs of legal-administrative decisions can be characterized in that the necessary information is scattered in the – geographic, organizational, social – space. It is theoretically easy to answer the question of how to make the decision-making process more algorithmic and automated in this situation. The data acquisition process (channels) need(s) to be reorganized, i.e. the data sources must be directly linked to the data request points. In the present situation, this is often not the case. An important finding of our research was that the necessary data is often provided by human «intervention» (for example when a parent requests family support, he or she must provide certification that he or she is the rightful parent of the child, so he or she must obtain a copy of the official birth registry). Instead of this procedure to obtain the relevant data, it would be much more efficient if the data sources and the data request points were directly interconnected.

Let us imagine a situation in which there are appropriate resources and intentions to reorganize the whole legal-administrative data acquisition process. The question can be raised how the new, totally interconnected data system can be modeled. Our answer is we must handle it as a communication (or data exchanges) process based on legal-administrative data when one of the most important questions is the legal qualification of data requested by the decision-makers.

It will be necessary to classify the types of documents that appear in this process and in general, in all of the administrative processes. It seems that three kinds of documents are used: registers, excerpts, and statements.

Registers are constantly changing and expanding data sets. As we mentioned earlier, there exist official state records systems consisting of different types of data, there exist non-governmental registries built by professionals (doctors, engineers, lawyers), and there exist other types of registries built by other institutional agents (schools, childcare facilities, etc.).

Excerpts are certified copies of some contents of registers concerning an individual (or an individual entity), like an identity card or driving license or vehicle registration certification). An excerpt must meet two requirements. It can be characterized by data structure (schema) that is identical to the structure of the original data source, and, of course, the data in the excerpt must match the original data. Because of the latter requirement, we need a tool to manage the relationships between different data sets, different documents that have the same content, but manifested (and accessible) in different forms. Theoretically, it is conceivable that the excerpts can be eliminated from the administrative procedure in the future, but even then, the question remains how we can provide decision-makers with valid data everywhere throughout the decision-making process.

Statements (or declarations) come from some individuals (including legal persons), and this type of documents will never disappear from the public administration process. There will always be data that is owned and only provided by civil clients and won’t be put together on a centralized register. When, in the case of unmarried parents, a father voluntary declares his paternity, that statement has to be put on the record; when a supported person’s bank account number changes, there is no one in the administration who will be aware of this change by default, it has to be declared. The statements (declarations) as such ensure that such data is included in the decision-making process.

There may be other types of legal-administrative-relevant documents that we need to include in a complete taxonomy (e.g. official letters, which are specialized extracts), and deeper and subtler characterization of legal information artifacts is needed.

If the decision points in the administrative process are characterized by documents (or data) and related acts (cf. Smith, 2012, 2014), it needs to be possible to distinguish between «good» and «not good» documents (or data) and «right» and «wrong» acts for formal representation. Document types can be described using the FRBR document representation model in order to distinguish between «good copies» (e.g., backup of a database) and «bad copies» (e.g. [use of] a lost and invalidated ID) for authenticity purposes. The FBRB acronym (Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records) refers to the IFLA (The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions) conceptual bibliographic models (IFLA Study Group, 1998).

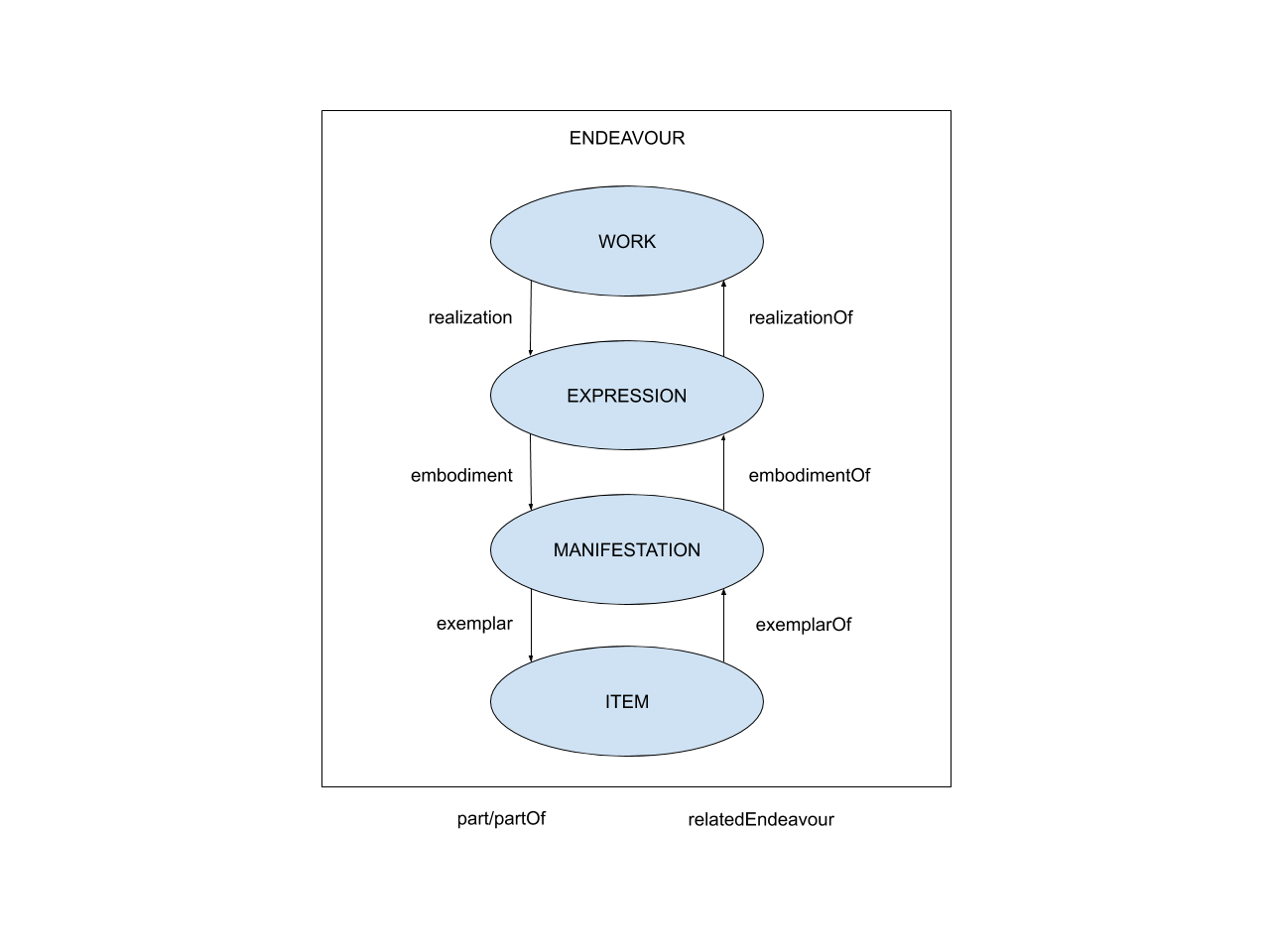

FRBR conceptualizes three groups of entities: products of (e.g., publications) and people or bodies responsible for the content of (e.g., authors); entities that serve as subjects of (concept, object, event, and place) intellectual or artistic endeavor.

The model distinguishes four levels of document descriptions (the product-group). There may exist multiple copies of a book in a library. The very same book may be published in different editions. One of the editions may be translated into several languages. In order to identify the sameness and differences of these, FRBR introduced the concepts of the work, expression, manifestation and item. The following figure shows their relations in the FRBR model.

Figure 1. The concepts and their relations describing publications in FRBR(FRBR Study Group 1998)

The FRBR model can be used when multiple copies, multiple manifestations, and multiple expressions with the same content exist. It is useful for describing books, films, music pieces, and it can be applied to describe databases as a special document type, as well. When someone has an entry in a state record, say, his or her birth date, and he or she must submit an excerpt to prove that he or she is eligible for some kind of family support benefit, then it is obvious that the two types/copies of data/documents are closely interconnected and should be identical. While we know (or at least expect), that the data is the same, the documents that carry the data are different. Excerpts are paper-based documents, official state record systems are increasingly made up of digital databases, but we can assume that certain data is recorded on paper in some official state registries. When a new record is built into a state registry based on an excerpt that «replicates» data of another (the «original») state record system, then we have two types of expressions (digital database and paper-based structured text), and three copies of the same data set (one paper excerpt, and twice a record in two separate databases). An important question is how to ensure that the data needed for the decision-makers is always valid, authenticated at any points of the whole process, and how to ensure that that the (data) content of the different copies of the same data set is identical.

The specificity of documents in administrative acts as compared to books is that they are unique (e.g., at any time only one ID card belonging to the same person should exist). Even copies must be unique. However, inheritance relationships similar to FRBR conceptualization should be used when describing records and extracts and statements. To every level of the concept «endeavor,» some contributor responsible for it can be assigned (author to the work, translator to the expression, publisher to the manifestation level). Similarly to every level of the data flow, some person or body responsible for data handling and validity can be assigned.

Each step in the administrative process is linked to documents/data. The authorized person shall take action that makes changes in an item of a document type. In terms of data processing, these actions can be recording, deletion, modification, checking or extraction. In terms of document signing, they can be authentication, certification or legal status attribution.

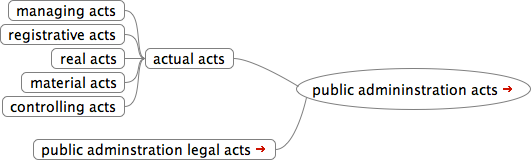

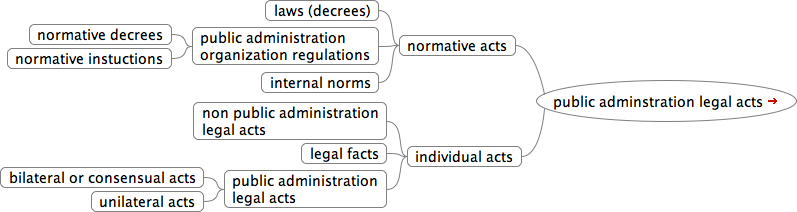

The administrative action typology is not codified in the Hungarian legal system (as opposed to the German legal system – cf. Singh 1985), but it is widely known as a theoretical conceptualization of the possible actions or acts in the public administration (Tamás 1997; Vértesy 2002). This conceptualization is very useful for describing the administrative process, but some points may be misleading.

Figure 2. Types of public administration legal acts (adapted from Vértesy 2017)

For example, the so-called registrative act is not considered to be a legal action subtype. Nevertheless, it is precisely the registration of legal status that is the most decisive action for the public administration. For instance, if a marriage is not registered for some reason after the legal ceremony, that marriage does not exist for the administration.

Figure 3. Types of public administration legal acts (adapted from ibid.)

If data acts are really constitutive for public administration processes, the above act typology seems to be inappropriate. The formal description of the process in terms of the data acts provides an opportunity for rethinking. What needs to be reflected to in the ontology is that

- for each status’ individualization a data act is needed connecting (directly or indirectly) to a register,

- if the registration fails, the individual legal status isn’t realized,

- in the public administration process, both data acts result in a change of status but not all of these are legal, and

- the legal statuses and their individualization involve a series of the so-called legal (or normative) positions (Hohfeld 1917), but we leave the discussion of this latter to another paper.

Acknowledgment

The research reported in this paper was supported by the Higher Education Excellence Program of the Ministry of Human Capacities in the frame of the Artificial Intelligence research area of Budapest University of Technology and Economics (BME FIKP-MI/FM).

References

Family Support Act 84/1998, at https://net.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=99800084.TV [in Hungarian]

Government Decree 38/2011. (III. 22.) on ensuring the processing of state records belonging to the national data assets [in Hungarian]

Hohfeld, W.N., Fundamental legal conceptions applied in judicial reasoning, In: Walter Wheeler Cook, (ed.), Fundamental Legal Conceptions Applied in Judicial Reasoning and Other Legal Essays, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1923, pp. 23–64.

IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records, Functional requirements for bibliographic records: final report. K.G. Saur, München 1998. (UBCIM Publications; New Series, vol. 19). (https://www.ifla.org/files/assets/cataloguing/frbr/frbr_2008.pdf)

Tamás, A., A közigazgatási jog elmélete. [Theory of Administrative Law] Szent István Társulat, Budapest 1997. (In Hungarian)

Vértesy, L., A közigazgatás cselekményei. [Administrative Acts] In: Temesi István (Ed.) Közigazgatási jog [Administrative Law]. Dialóg Campus, Budapest 2018, pp 224–242. (In Hungarian)

Searle, J. R., The Construction of Social Reality. The Free Press 1995.

Singh, M. P., German Administrative Law in Common Law Perspective. Springer, Berlin 1985.

Smith, B., How to Do Things with Documents. Rivista di Estetica, 50 (2012), pp. 179–198.

Smith, B., Document Acts. In: Anita Konzelmann-Ziv, Hans Bernhard Schmid (eds.), Institutions, Emotions, and Group Agents. Contributions to Social Ontology (Philosophical Studies Series), Springer, Dordrecht (2014) pp. 19–31.