1.

Introduction ^

The development of information society and digitalisation, contributed to creating a new working surroundings in which it is not any more important where the employees work, but what digital technologies are at their disposal. Phrases such as global workplace, electronic workplace, digital workplace, teleworking, home office are increasingly present both in business environment as well as in labour law.

Fast development of internet technologies supported this change. Wide accessibility of high-speed internet, working in cloud surroundings, the use of various communication programmes and apps enabled not only work but also communication with other colleagues in real time and to the extent of which it was necessary. The idea of teleworking was additionally prompted by the need of protecting workers during the Covid-19 pandemic, when numerous companies, whenever it was possible, having in mind the nature of the workplace1, have organised a remote work of their employees, providing them with all the necessary equipment and resources including both hardware and software. One of the consequences of the pandemic is certainly the change of the concept of workplace in direction of increased use of telework or home office.

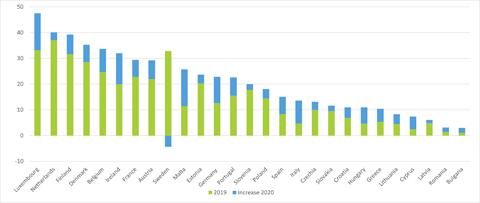

Figure 1. Eurofound diagram on increase of telework 2019/20202

In the above diagram, increase in home office work in 2020 comparing to pre-pandemic 2019 was present in almost all countries of the EU.

According to survey carried out by Statista Austria in January 2021, 41 % of employees in Austria were working partly or completely in home office.3

Many companies will keep to a certain extent the possibility of working remotely, having for them numerous advantages, such as decreasing office space and accompanying rental and other expenses, savings in the use of electrical energy, heating, commuting hours and expenses for workers etc. It will certainly depend on industry and the qualification of employees. A possibility of organising the work remotely or in the home office increases with the qualification and information technology skills of employees.

However, working remotely opens many legal questions, from defining a telework, home office as the most often feature of telework, regulating insurance during work, working time, to surveillance and protection of privacy. Being a new concept, many national employment laws did not have home office or telework regulated in their national legislation, which prompted states to enact new laws that would regulate this issue. While there is still a diversity of enacted telework national legislation in the EU, one of the states that have included home office in their national laws is Austria, which passed a set of amendments into labour and tax laws covering home office work, which in respect of labour law and insurance law entered into force on 1 April 20214, while tax law provisions have a retroactive application as from 1 January 20215.

Collective bargaining has a very important role in labour law, and in supporting the telework idea. Thus, the home office is already included in several collective agreements6 in Austria and is expected in the future to be more and more present in collective bargaining. Collective agreements regulate in detail the scope of home office or telework, arrangement in writing for home office work, duration, working time etc.

2.

Digital workplace v. home office and telework ^

Digital workplace implies an infrastructure which enables employees to have access to all prerequisites that they need to do their job, regardless of whether they are in business premises of their employer, at home, or at a third location. However, digital workplace as a result of a digital revolution has made an impact on legislation and can be legally observed from more aspects.

Many companies base their work on data which is stored on servers physically outside of their business premises, and which is accessed remotely, protected with a specific key and access requirements. Physical location of servers that keep and process data is also relevant when speaking of privacy protection, especially having in mind the recent data protection requirements in the EU, stipulated in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The placement of servers outside of the EU, in case personal data is stored and processed therein, comes under the scrutiny of the GDPR. The data protection system is complex, especially when it comes to data transfer outside the EU, when special legal grounds must be observed for the transfer of data, such as adequacy decisions, appropriate safeguards, etc. While business data may not necessarily include personal data, some of them do, such as personal data of employees, visible for example in employee file, data of clients especially in companies working with payroll, sensitive data of patients in medical institutions, etc. Therefore, by organising telework, companies must have in mind not only the prerequisites of the national legislation regulating home office or telework, but also data protection legislation, national and EU, especially when servers on which data is stored or processed are located outside of the EU.

Home office involves a concept of performing duties that arise out of employment and accessing all data necessary for performing those duties, from one’s home. According to recently enacted changes to employment set of laws in Austria, working in home office includes a “work that is performed by an employee from a home on a regular basis”7.

However, the Collective Agreement in the IT Sector provides for remote work, without defining a place of work as a home. Work is performed at a previously agreed location outside of the permanent company premises in agreement with the employer.8

The Collective Agreement in Metal Industry9 provides for a remote work especially in the home of the employee, putting the accent on employee’s home, unlike the legislative terminology of “a home”.

The third possibility covered by the digital workplace sphere is accessing the digital workplace from a place that is neither home nor business premises of the employer. For example, a rented shared space, café, restaurant, etc. However, legislators did not include this part of remote working in a home office concept envisaged by law, providing that the work can be performed from one’s home. A question of working at an agreed location which does not have to be a home, may be still open to interpretations, having especially in mind the Collective Agreement in the IT Sector. If collective agreements are meant to be more favourable to employees than laws, can we say that for employee is more favourable to work at a location that does not have to be a home, nor business premises of the employer? However, we should consider the overall legislative picture, regarding the home office in Austria, which tends to regulate the home office or telework activities in a home. We may recognise that through the regulation of responsibility of members of a household for damages10 or the provisions of the Amendments to the Law on Labour Inspection according to which labour inspection is not authorised to enter the home in which employee carries out his or her activities in the home office. Income Tax Law11 provides for a home office flat rate for working in a home within a special arranged working place inside one’s home.

Therefore, we may say that a digital workplace is a concept wider than the concept of home office but is mostly used for the purpose of working in a home office, making the employee mobile, but under the limitation that the national labour legislation provides.

3.

Concept of home from office perspective ^

The concept of a home has been well defined and analysed through the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental freedoms (ECHR) and the case-law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Respect of home provides for a wide net of positive and negative obligations for the State: negative ones, implying the protection against interference by State bodies, and positive implying an efficient machinery of the State which must be at one’s disposal in case one’s “home” was interfered with by another natural person. This concept has been also envisaged by the Human Rights Charter of the EU.

While “home” in light of the ECHR is normally defined as a physically defined place where private life and family life develops, in the case of Niemietz v. Germany the European Court has widened the concept of a “home” giving the possibility that the word “home” may be extended to a professional person’s office, and thus to business premises.12 The Court, in its judgment, pointed out that professional or business activities may be conducted from a person’s private residence and from that reason stood against a narrow interpretation of the word “home”. Therefore, the concept of a home office was supported by the European Court already in 1992.

The concept of one’s home is recognised by national legislation in Austria also when speaking of a home as one’s place of work, or home office. In that regard, one part of a “home office” legislative package were above mentioned Amendments to the Law on Labour Inspection, according to which bodies of labour inspection are not authorised to perform their duties by entering the apartment of an employee where he or she works in a home office.13

Therefore, the legal protection of a home as a such is given prevalence over the need of state bodies to control the working surroundings, which normally happens on business premises. Although there is a justified need to make sure that the employee works in accordance with all legal standards applicable in working surroundings, the protection of home, including the private sphere of the employee has been given the clear advantage. Therefore, it is on the employer to ensure that all the necessary preconditions are met for the protection of employees during their work at home, including the protection of employees’ health,14 and measuring of the working hours in accordance with the judgment of the European Court of Justice that is further referred to.

On the other hand, the responsibility of employees is also widened to family members in a home office.15 Normally, family members are excluded from the employee responsibility on business premises, but the legislator had in mind normal activities in one household and has proven flexibility in this context.

When it comes to accidents at the workplace, they usually cover accidents at a workplace and on the way to work and back. But when it comes to home office, we may question what is considered to be “on the way to work”. In a recent judgment of a Court for Social Affairs in Munich, Germany, an accident of an employee in his home office on his way from the desk to the bathroom was not considered a work accident. The Court has explained, inter alia, that the employee has used stairs on his way to a personal space (bathroom), which was not in a company interest but in his private interest16

Having in mind that the home office work is a very young legal concept, the building of jurisprudence in this area has yet to follow.

4.

Legal preconditions for digital workplace ^

While the digital workplace in business surroundings of an employer does not require separate legal arrangements, the digital workplace in a home office certainly has different legislative preconditions. The home office must be arranged with the employer on a voluntary basis. In Austria, an employee wishing to work in a home office must enter into an agreement in writing with his employer providing that he or she will work in a home office. That agreement is separate from the job contract, which may or may not be concluded in writing, and may also be entered into after constituting a labour relation and ended regardless of ending labour relation. That means that an agreement on home office has a separate legal life comparing to the labour relation, but must of course be within the time scope of the working relation. However, the home office is based on freewill of an employee.

5.

Working time and digital workplace ^

One of the earliest ideas in the fight for employees’ freedoms concerned the limitation of working time. The first Convention that the International Labour Organisation has adopted was the Hours of Work (Industry) Convention enacted in 1919, which introduced the principles of the 8-hours day and the 48-hours week.17 Breaks during working hours, rest between two days, and the right to paid leave are the achievements of the 20th century. The Charter of the Fundamental Rights of the European Union has proclaimed the right of every worker to a limitation of maximum working hours, to daily and weekly rest, and paid leave.18 The same spirit has been reiterated in the Working Time Directive.19

Overtime, prolonged work, work during weekends and holidays has been in detail regulated through collective bargaining in Austria, and the Law on Working Time.20 However, limited working time is a challenge when it comes to work in a home office. The availability of working devices, digital technologies and the lack of control can pose a danger to prolonging working time outside of agreed or allowed working time. The danger of non-recording working time was recognised by the European Court of Justice, which has in 2019 adopted a judgment21 obliging the Member States to require employers to “set up an objective, reliable and accessible system enabling the duration of time worked each day by each worker to be measured”. Having in mind that, when it comes to control, the labour inspection is not allowed to enter the employees’ home, it is especially important that employers see to it that home office employees measure correctly their working time, and that employers control it.

Two concepts that may interfere with working time also at home office in Austria are “on call”22 and “readiness to work”23. While this is understandable in certain professions, such as medicine or fire departments, more and more other branches, in which urgency is not so pronounced, like IT technologies, are faced with the potential prolonging of working time, when work is organised from the home office.

“On call” entails availability of an employee outside of office hours, but not in a specific place, which may vary and include also a café, restaurant or unknown place. It is limited to 10 days a month or 30 days during a period of 3 months. As the employee does not work, but is only available, a crucial difference comparing with home office can be noticed. Still, being “on call” prevents an employee from being completely detached from work which he or she would normally do between two working days and that is the reason of its legal limitation. Moreover, being at home, the employee is more exposed to being available then in business premises, which is also clearly present in “readiness to work”. This should be kept in mind when arranging work in home office as well.

Negative consequences of availability after work, such as decrease of rest between two working days, interference in the private life, not efficient use of “free” time, are inherent not only to the worker but to his family and private circle as well. Work-life balance is impacted. The International Labour Organisation has drawn attention to the possibility of blurring the lines between private and working life, because teleworkers are often faced with unconventional schedules and informal working, contrary to working time in the office when usually there is a clear timeline of work and break.24

6.

The right to disconnect ^

A few years ago, with France enacting in its labour law provisions on the right to be disconnected,25 the issue of availability after working hours came on the scene in the labour law in Europe. Being the legacy of the ILO, and of numerous fighters for workers’ rights, clear separation of working time and rest time has come into question with the progress of digital technologies, enabling anyone to be able to check up their business e-mail or a web portal at any point of time and from any place. The line between the end of work and begin of rest time is not clear anymore. Numerous negative consequences on employees that stay available after work, such as not effective rest time, burn out, etc. have brought the discussion about this issue on the legislative table of the EU. Thus, the European Parliament has brought an initiative to the European Commission to propose a law to enable workers to disconnect after working hours. 26

The right to disconnect becomes especially important in a home office, the employee having all prerequisites to stay connected at his or her home. Dangers of burning out, working not recorded hours after normal working time, will have to be recognised and closely monitored by both employees and employers, so that any negative consequences thereto are prevented.

7.

Digital workplace and privacy ^

ECtHR has dealt with privacy at workplace on a several occasions27. In the case of Barbulescu28 where the subject of proceedings was privacy of digital correspondence of an employee with his fiancée which was intercepted by the employer, the ECtHR has come up with standards which have to be met in order that right of privacy of online communications of an employee is protected29. While it is understandable that employers wish to decrease the possible use of private online communications during working hours, these standards aim to make employees aware of the possibility of intrusion into their privacy, such as a clear and in advance notification. When employees do have high expectancy of privacy or are not informed about the possibility of interfering in that privacy, the line between protection of employers’ interests and violation of the right of privacy of employees becomes tiny.

The expectancy of privacy, which is a standard for determining of a likeliness of a violation of the right to the respect of privacy according to ECHR standards, is normally the highest at one’s home, and therefore the possible violation thereof should be scrutinised at the highest level. In one’s home office, a possible violation of privacy of employees would also be interconnected with the possible violation of the right to respect of the home.

Video surveillance of employees at their working place has already been determined as presenting a violation of the rights to respect for private life of employees.30 Surveillance of employee keystrokes, and of mouse movements are very unlikely to have legal grounds31 in a digital workplace. It is unimaginable that any such surveillance in a home office would meet human rights standards of protection of privacy and moreover of protection of the right to respect for one’s home.

Therefore, the requirement for the protection of privacy in a digital workplace is even more pronounced than in a normal business environment. Information technologies, which are a precondition for a full functioning digital workplace and a home office, can at the same time be a danger or a temptation for employers to stay in line with the protection of employees’ privacy. It is very important that clear rules exist as to monitoring of employees’ working time, completion of tasks, and other features that are important for the accomplishment of business success. But at the same time, loyalty and mutual understanding between an employee and an employer can be the best unwritten rule under which privacy would not be undermined.

8.

Conclusion ^

The digital workplace can be regarded from several aspects which are interconnected and therefore presents a challenge to both legislators and legal practitioners. In its most visible form, home office, putting together the concept of work and a concept of home has both advantages and disadvantages. Prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic, the use of home office use has risen thorough the EU and will have its consequences also in labour law. The IT surroundings of a workplace give many benefits to the economy but pose a challenge to regulating labour concepts out of usual business premisses. Thus, depending on circumstances, digital workplace regulation may involve data protection requirements, in some instances even international ones, like transfer of data, labour law adjustment, development of jurisprudence, involvement of protection of employee, both physical one, through health and ergonometric requirements, and the protection of his or her privacy. This complex issue therefore requires a multidisciplinary approach so that the digital workplace, including the home office, are brought to the highest standards.

9.

References ^

Cosabic, Data Protection of Employees – Certain Aspects of ECHR and GDPR Protection, Proceedings of the 24th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2021.

Predotova, VARGAS LIAVE, Workers Want to Telework but Long Working Hours Isolation and Inadequate Equipment Must be Tackled, Eurofound, 06 September 2021.

European Commission, Science for Policy Briefs, Telework in the EU before and after the COVID-19: where we were, where we head to, 2020.

International Labour Organization, Practical Guide on Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, 16 July 2020.

Mohr, Arbeit im Home Office während der Corona-Krise in Österreich 2021, Statista, 19 January 2021.

Niemietz v. Germany, judgment of the ECtHR, issued on 16 December 1992.

Judgment of the ECtHR in the case of Lopez Ribalda and Others v. Spain, issued on 17 October 2019.

Judgment in the case of Karin Köpke v. Germany, issued on 5 October 2010.

Judgment of the ECtHR in the case of Barbulescu v. Romania, issued on 5 September 2017.

International Labour Organisation, Teleworking during the Covid-19 Pandemic and beyond, a Practical Guide, Geneva, 2020.

Quoted laws and collective agreements.

- 1 Predominantly high skilled workers in ICT technologies are affected by telework, and to a certain extent the education sector, consultancy, and the likes (see for example https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/default/files/jrc120945_policy_brief_-_covid_and_telework_final.pdf, page. 1).

- 2 Predotova, Vargas Liave, Workers Want to Telework but Long Working Hours Isolation and Inadequate Equipment Must be Tackled, Eurofound, 06 September 2021, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/publications/article/2021/workers-want-to-telework-but-long-working-hours-isolation-and-inadequate-equipment-must-be-tackled.

- 3 https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/1109368/umfrage/arbeit-im-home-office-waehrend-der-corona-krise-inoesterreich/Details: Austria; Unique Research; 11.–14. January 2021; 800 Surveyed; from 16 years of age; persons living in Austria; Online-Survey.

- 4 https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2021_I_61/BGBLA_2021_I_61.pdfsig.

- 5 The issues of home office thus legally regulated include the feature and scope of home office, as provided for in Amendments to the Labour Contract Law, BGBl. I Nr. 131/2020 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021, issues of compensation for damages regulated in Amendments to the Law on Responsibility of Employees, BGBl. Nr. 169/1983 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/202, inspection control with regard to home office in Amendments to the Law on Labour Inspection, BGBl. I Nr. 100/2018 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021, insurance in the Amendments of the Common Social Insurance Law, BGBl. I Nr. 28/2021 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021, etc.

- 6 Collective Agreement for Employees of Service Providers in the Field of Automatic Data Processing and Information Technology, Collective Agreement for Employees in Metal Industry, Collective Agreement for Electricity and Electrical Engineering.

- 7 § 2h (1), Amendments to the Labour Contract Law, BGBl. I Nr. 131/2020 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021.

- 8 § 9, 2, Collective Agreement 2021 for Employees of Service Providers in the Field of Automatic Data Processing and Information Technology.

- 9 § 14, (1) Collective Agreement for Employees in Metal Industry, 2021.

- 10 Amendments to the Law on Responsibility of Employees, BGBl. Nr. 169/1983 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021.

- 11 § 16 (7a) Amendments to the Income Tax Law, BGBl. I Nr. 52/2021.

- 12 Niemietz v. Germany, para 30, judgment issued by the European Court of Human Rights on 16 December 1992.

- 13 § 4 Ammendments on the Law on Labour Inspection, BGBl. I Nr. 100/2018 / BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021.

- 14 See the Recommendations of the Ministry of Labour in ‘Guidelines for Ergonomic work in home office and a Checklist for a safe and healthy work at home’ to implement provisions of the Employee Protection Law also in Home Office.

- 15 § 2, (4) Amendments the Law on Employee Responsibility, BGBl. I Nr. 61/2021.

- 16 SG Munich judgment 04.07.2019 – S 40 U 227/18, para 28 of the judgment, https://www.gesetze-bayern.de/Content/Document/Y-300-Z-BECKRS-B-2019-N-16645?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

- 17 https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/working-time/lang--en/index.htm.

- 18 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012P%2FTXT, Article 31.

- 19 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012P%2FTXT.

- 20 Law on Working Time, BGBl. Nr. 461/1969.

- 21 https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-05/cp190061en.pdf.

- 22 “Rufbereitschaft”.

- 23 “Arbeitsbereitschaft”.

- 24 International Labour Organisation, Teleworking during the Covid-19 Pandemic and beyond, a Practical Guide, Geneva, 2020, https://www.ilo.org/travail/info/publications/WCMS_751232/lang--en/index.htm.

- 25 So called El Khombri law, named after the minister Myriam El Khomri who induced the labour reform at issue August 2016. It provided that companies with more then 50 employees should adopt procedures in order to enable the employee to exercise a right to be disconnected with a view to ensure the respect for periods of rest and leave as well as for private and family life. The modality of providing for such rights is upon the companies. See Cosabic, https://politicalanthropologist.com/2017/05/08/right-disconnected-wave-catch/.

- 26 https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20210114IPR95618/right-to-disconnect-should-be-an-eu-wide-fundamental-right-meps-say.

- 27 See for example judgment of the ECtHR in the case of Lopez Ribalda and Others v. Spain, issued on 17 October 2019, judgment in the case of Karin Köpke v. Germany, issued on 5 October 2010.

- 28 Judgment of the ECtHR in the case of Barbulescu v. Romania, issued on 5 September 2017.

- 29 See Cosabic, Data Protection of Employees – Certain Aspects of ECHR and GDPR Protection, Proceedings of the 24th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2021, p. 316.

- 30 See the judgment of the ECtHR in the case of Lopez Ribalda v. Spain.

- 31 Cosabic, Data Protection of Employees – Certain Aspects of ECHR and GDPR Protection, Proceedings of the 24th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2021, p. 317.