1.

Adding support for VAT in ERP systems ^

Information technology as such supports an increasing number of everyday activities. Although no definition of enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems explicitly mentions that ERP systems should also support paying value added tax (VAT), companies appear to implicitly expect extended support for handling taxation from ERP systems. The statement that VAT (or taxes in general) is not a part of ERP system definition is based on a query (as of 29 September 2008) at the Web of Science database for the topic «enterprise resource planning» AND tax where none of 484 Web of Science articles mentioning the string «enterprise resource planning» in the text, contains the string «tax». This also implies that it apparently does not make sense to search for «value added tax», as the term «tax» was not found. Therefore, only the acronym of value added tax, i.e. «VAT» was included in the second query topic «enterprise resource planning» AND vat. Again, there were no articles found. A known limitation to this investigation approach is that some of the articles in the database are available only as scanned pages, i.e. information about some articles contains only the author(s) name, the title and the abstract, not the full text of the articles. A relevant example is (Fisher, Fisher, Kiang et al., 2004), which discusses ERP system selection criteria and mentions «international tax support» as one of the proposed criteria.

Nowadays, ERP systems, generally, support VAT but most often end-users have to be cognizant of the law and only document its use using their ERP system. Even in case the ERP system informs the end-user of the appropriate legal actions, it is achieved only by hard-wiring of interpreted VAT rules (in a form of a code or a definition file) into the ERP system.

Having a system which would advise the end-user what to do based on the full understanding of the VAT law, should optimize business processes – schedule payment of VAT or claim of VAT offset, exploit deadlines, and even improve the overall price of goods and services for customers (it might suggest that the company registers voluntarily as a VAT payer in certain countries, where it exports, in case VAT is lower in the other than in the home country).

Hard-wiring is not the best possibility in case the VAT law changes often, or in case the vendor would like to sell its ERP systems in several countries, requiring thorough localization of the hard-wiring present in the product. Another problem is that hard-wired VAT rules are often re-interpreted and only then deployed. The result is that even small changes in the law can lead to rather large changes in the ERP system code or in the definition files because even one rule, having been changed, could have been bundled with many other rules having stayed the same.

An obvious solution would be to empower law experts to input VAT rules into the system (possibly through a user-friendly front-end, not necessarily a part of an ERP system). The underlying problem is, how to set up an interface – what should it allow to model. So far, we have not found any classification of VAT rules, which could be used to set up an environment, in which lawyers (or domains experts) could input VAT rules. This lack in literature was the motivation for the paper. The two research questions that we hope to (partially) answer by this paper are:

What types of legal rules exist in VAT laws that are relevant for modeling in ERP systems?

Given a concrete answer to the above (in the form of a framework for legal rules), is the framework sufficient for classifying all VAT articles?

The answer to the first question is the proposed framework in the third section of the paper, in particular the answer is the set of possibleclasses of articles in the framework. The answer to the second question isYes: To back up our claim, we classified the European Council directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 on the common system of value added tax (The Council of the European Union, 2006) in the fourth section of the paper. As it has been possible to classify all the articles, we argue that the framework is sufficient. And as we used all categories (although some only a few times), it can be concluded that all the categories in the proposed framework are necessary. We are currently developing an automated system prototype for VAT support in ERP systems that utilizes the framework.

The paper is organized in the following way: Section 2 provides insight into VAT legislation, Section 3 describes the framework for classification of VAT articles, Section 4 presents the actual classification of articles in (The Council of the European Union, 2006), and the fifth Section 5 concludes.

2.

VAT Legislation ^

In this section, we describe features of the legal domain that are relevant with respect to modeling VAT rules. The description is mainly based on the European directive on the common system of value added tax (The Council of the European Union, 2006) but it is also applicable to country specific VAT acts.

From a top-level perspective, legal documents are structured collections of uniquely identifiable pieces of natural language text written in legal vernacular. Here, we describe the structure as it occurs in (The Council of the European Union, 2006). Our description shall take the notion of anarticle as its starting point. Articles in the directive are uniquely identifiable (sequentially numbered from 1) and are grouped using the following constructions: title, chapter, section and subsection.

The grouping constructions are used for two related purposes. One is to be able to reference a collection of articles, namely, the ones having a given grouping construction as an ancestor, while the second is to group articles in a meaningful way (for people). Because of the latter, grouping constructions carry headlines (short descriptions), not only identification numbers. But while articles are uniquely numbered on a directive-wide basis, grouping constructions are numbered sequentially from 1 within their enclosing construction, e.g. there can be a Chapter 2 of Title 1 as well as a Chapter 2 of Title 2 etc.

Hierarchical structure can also be imposed within individual articles. The intra-article grouping constructions are enumerated in a fashion similar to chapters, sections etc. and serve the same purposes of referencing and grouping related legal statements.

Being able to reference (collections of) articles is important as the provisions of (a part of) one article are often subject to the content of another. Similar to many other situations, e.g. file systems, references can be absolute or relative. Absolute references begin with either a title or an article number while relative references are relative to the place at which they occur. An example of relative referencing is Article 2 of (The Council of the European Union, 2006). It consists of three paragraphs, each of which has several schedules and points. In paragraph 2 schedule (a), a reference is given as follows: «For the purposes of point (ii) of paragraph 1(b),...». In Figure 1 we have included a page from the Council Directive in order to show how the grouping constructions are used.

Another relevant issue related to structure and references is the common separation of (main) rules and their exceptions. The separation comes about because of the way in which legal documents evolve over time due to the fact that legislators cannot foresee all possible future usages, see (Prakken, 1997) for an elaborate discussion.

3.

A framework for classification of legal articles pertaining to VAT ^

It is possible to classify articles in several ways. Our aim has been to devise a classification that can support and guide the development of a formal mathematical model of the articles for use in automation in ERP systems. One of the benefits of having such a model is that it can alleviate the following problems that ERP systems such as Microsoft Dynamics NAV and SAP suffer from today:

| 1. | How can we be or make sure VAT is calculated correctly? |

| 2. | It is hard, if not impossible, to know exactly what rules ERP systems support. |

| 3. | It is complex due to the large number of countries and rules. |

Not all the content of a VAT law is relevant for explicit modeling in an ERP system, the foremost example being rules specifying procedures for updating the legislation such as Article 8 of (The Council of the European Union, 2006). As Čyras, Lachmayer (2008) state, «legal reasoning, especially by non-experts in law, is driven primarily by goals then by norms». Our goal is to pay VAT, i.e. to model rules that are related to VAT and relevant in an ERP setting. In order to do this, we need to both identify the relevant rules and to develop a modeling methodology. To facilitate these two tasks we undertook an enquiry into the nature of legal statements based on (The Council of the European Union, 2006), which has resulted in the following classification scheme for rules:

Definitions are legal statements introducing new concepts, which can be used in rules. Definitions can be either explicit, such as the definition of taxable person :

[Article 9, paragraph 1] (The Council of the European Union, 2006)

or implicit in which case a concept is used in a rule without any prior (or trailing) explicit definition.

Classifications are legal statements relating concepts and legal statements (through references) to each other. Classifications can state rules that may be followed as well as rules that must be followed. Often classifications take the form X should/shall be treated as Y, which is the case e.g. in paragraph 1 of Article 15 in (The Council of the European Union, 2006) which reads:

[Article 15, paragraph 1] (The Council of the European Union, 2006)

Classifications can also be implicit. This can happen in the situation where common sense determines how concepts are related to each other. An example is that the concepts vehicle and vessel are assumed to be non-overlapping.

Workflows are legal statements describing relative or absolute timing of events. They can be seen as a subcategory of classifications but deserve special attention because we believe they will be more challenging to model than non-workflow classifications. An example is paragraph 3 of Article 17 in (The Council of the European Union, 2006) which reads:

[Article 17, paragraph 3] (The Council of the European Union, 2006)

Clarifications are legal statements clarifying the meaning of definitions and classifications. An example is Article 25 in (The Council of the European Union, 2006) which reads:

(a) of a document establishing title;

(b) the obligation to refrain from an act, or to tolerate an act or situation;

(c) the performance of services in pursuance of an order made by or in the name of a public authority or in pursuance of the law.

[Article 25] (The Council of the European Union, 2006)

Legal statements that fall outside these categories can be classified as well but are not interesting with respect to our modeling. Examples of such category are rules governing necessary measures and regulatory behavior, intention and applicability, and change of directive. Amongst others, this category contains articles 19, 23 and 34.41 of (The Council of the European Union, 2006).

Each article can belong to one or more categories. For example, classifications may include implicit definitions. When both are manifest in the same sentence, it is not possible to split them in any reasonable way without constructing a new representation of the article. When an article includes a classification and a workflow, it is usually possible to split them meaningfully because they are addressed in separate paragraphs of the article.

4.

Classification EU Directive 2006/112/EC ^

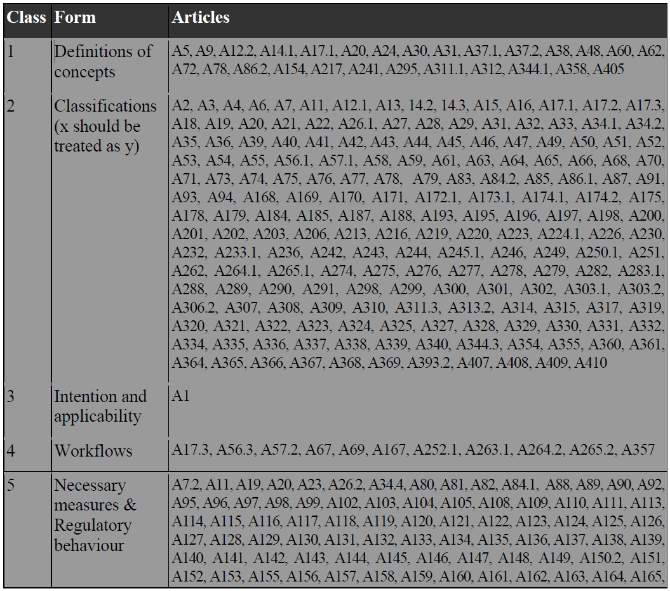

The classification of (The Council of the European Union, 2006), which is presented in Table 1, may be considered as a test of the proposed classification framework.

Probably the hardest part of the process was to distinguish between explicit definitions and classifications. An example could be paragraph 1 of article 38 in (The Council of the European Union, 2006) which reads:

[Article 38, paragraph 1] (The Council of the European Union, 2006)

The problem with the above paragraph is that it could read either as «the place where that taxable dealer has established his business …» should be treated as «the place of supply» (i.e. paragraph being a classification), or «the place of supply» is «the place where that taxable dealer has established his business…» (i.e. paragraph being explicit definition of the place of supply).

5.

Conclusion ^

We tried to answer two research questions in this article. The first was aimed at classifying the types of legal rules there exist in VAT laws relevant for modeling in ERP systems and providing a framework for classification of actual legal text. We proposed a framework with the following categories: definitions, classifications, workflows, clarifications, intention and applicability, necessary measures and regulatory behaviour, and change of directive. The first four categories are relevant for modeling (though it could be discussed whether the fourth one is useful for anything else than making sure that the articles belonging to the first three categories were understood correctly).

The second research question was whether the proposed framework is sufficient for classifying all VAT articles. In order to test the hypothesis, we classified the European Council directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 on the common system of value added tax (The Council of the European Union, 2006) according to the framework. As it has been possible to classify all the articles, we argue that the framework is sufficient. And as we used all categories (although some only a few times), it can be concluded that all the categories in the proposed framework are necessary.

The remaining challenges are to explicitly define hierarchies and whether certain terms are overlapping or non-overlapping. Future research will involve classification of national VAT acts (making a few categories redundant), and comparison of VAT acts of European Union counties to the directive. We are in the process of modeling VAT rules using the Language for Logical Modelling of Business Rules and Regulations (LLMBRR) and implementing an automated system based on this language. Last but not least, we hope that, in the final stage, it will be possible to identify relevant sentences in the law automatically, as it is already possible to do with newspaper articles in English, French, and even Arabic, for event information extraction, as shown in (Faiz, 2006).

6.

References ^

V. Čyras, F. Lachmayer (2008). Transparent complexity by goals. In Electronic Government, 7th International Conference, EGOV 2008 (Turin, Italy, August 31 - September 5, 2008). Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5184, Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 255-266.

D.M. Fisher, S.A. Fisher, M.Y. Kiang et al. (2004). Evaluating mid-level ERP software. Journal of Computer Information Systems, vol. 45, no. 1, pp. 38-46.

H. Prakken. Logical Tools for Modelling Legal Argument: A Study of Defeasible Reasoning in Law. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1997.

E. Heinäluoma. Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006 on The Common System of Value Added Tax. Official Journal of the European Union (English edition), Volume 49 11(L 347), December 2006.

M.J. Sergot, F. Sadri, R.A. Kowalski, F. Kriwaczek, P. Hammond, and H.T. Cory. The British Nationality Act as a Logic Program. Commun. ACM, 29(5):370-386, 1986.

I.S. Henriksen. Modeling Law: A Logical Model of the Danish Act on Social Pensions and a Web-tool. Master Thesis, IT-University of Copenhagen, March 2002.

E.R. van der Meer, I.S. Henriksen, and H.R. Andersen 2003. Using configuration technology as the core of a legal decision support system. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (Scotland, United Kingdom, June 24–28, 2003). ICAIL '03. ACM, New York, NY, 147-151.

R. Faiz (2006). Identifying Relevant Sentences in News Articles for Event Information Extraction. International Journal of Computer Processing of Oriental Languages, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1-19.

Frantisek Sudzina, Copenhagen Business School, Center for Applied ICT

Howitzvej 60, 2000 Frederiksberg, DK

Morten Ib Nielsen, Jakob Grue Simonsen, Ken Friis Larsen, Department of Computer Science, University of Copenhagen (DIKU)

Njalsgade 126-128, 2300 Copenhagen, DK, simonsen@diku.dk

- 1 Article 34.4 is a shorthand notation for paragraph 4 of Article 34.