1.

Introduction ^

Disciplines such as business management, engineering, and computer science use a variety of methods to manage risks of different kinds related, for instance, to products, markets, or information systems. The «risk» may be an accident, an economic loss, or an event with negative effects on the security of a system. In this context, risk is often estimated based on its likelihood and its consequences. For example, if the captain of the Titanic had had complete knowledge of the limitations of the ship, he could have identified the risk of the ship colliding with an iceberg. The likelihood of this risk could have been estimated as possible, and the consequences could have been estimated as «a high number of casualties,» which would indicate a high risk. Professionals from different disciplines use dedicated but similar risk management methods, some of which potentially could also be applied to the analysis of legal issues. This could be called «legal risk management,» and it would consist of coordinated activities to manage both legal risks and other risks that could be «treated» by legal means.1 Legal risk is difficult to define,2 but for the purposes of the present paper, we can use the term simply to denote any risk related to legal problems. The latter term, legal problem , refers to a set of facts and legal norms that are applied in making a decision, regardless of who is the decision-maker. This paper focuses on a possible approach for the visualisation of legal risk in a graphical model.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an example of a risk, which will be used to present the approach for visualisation. Section 3 motivates the use of visual models to support legal risk management. Section 4 presents requirements that should be fulfilled by the graphical language. Section 5 contains some diagrams to illustrate the graphical models, including a model of the initially presented example. The paper closes with some concluding remarks in Section 6.

2.

Example ^

The visualisation is illustrated based on the following risk identified and described by the software provider SAP in their annual report:

This example illustrates how SAP refers to legal and contractual issues when identifying risk related to legal claims. The risk estimation is somewhat hidden in the text, but SAP offers an estimate of the risk value in the concluding statement «it is unlikely that our planned results will be significantly impaired». This statement depends on the legal validity of the contractual liability limitations. Such an analysis has to imply a considerable degree of co-operation of different professionals in order to achieve a holistic risk assessment. The legal method used to answer the legal questions needs to be combined with risk management methods that are non-legal in their origin, but that could add value to some of the services provided by lawyers.

A risk description is typically a descriptive proposition , like the following proposition found in the above SAP annual report:4 «We believe it is unlikely that our planned results will be significantly impaired by product defect claims from SAP customers.» Given the inherent uncertainty about the future, such propositions typically contain a probabilistic qualifier similar to SAP’s use of the word «unlikely» in the above example. Moreover, the risk description typically includes a description of the value of the consequences for the stakeholder’s objectives. In the above example, this is somewhat hidden in the expression «our planned results will be significantly impaired». The planned results are SAP’s objective, and the significant impairment would be the description of consequences. This would lead to the following simple risk table:

| Risk | Effect on objective | Likelihood | Consequence |

| Product defect claims | SAP results | Unlikely | Significant |

Legal aspects can be adequately addressed if the above is complemented with propositions about norms . An assessment of the above risk requires SAP to refer to relevant legal sources, including contracts: «Our contractual agreements generally contain provisions designed to limit SAP’s exposure to warranty-related risks.» The following sentence then includes at least a hint of a normative statement: «However, these provisions may not cover every eventuality or be entirely effective under applicable law.» The interesting part here is the latter aspect, according to which «the provisions may not be entirely effective. This «effectiveness» points to the validity of the contract provision in the relevant jurisdiction. However, the phrase «may not be entirely effective» also includes the qualifier «may,» which could be seen as a probabilistic statement about legal uncertainty. The proposition «may not be effective» implies that there is uncertainty about the validity of the respective contract provisions.

3.

Why visualise legal risk? ^

In the above example, several professionals would have to collaborate: an engineer would be able to estimate the likelihood of the technical failure; a lawyer may need to be consulted when the legal consequences are assessed, and a manager would need to estimate the financial consequences. Therefore, it would be useful to convene different professionals in order to discuss and estimate the risk consistently. This clearly requires communication and mutual understanding of the others’ disciplinary perspectives. Such communication may be challenging due to the different methods and concepts used by the different disciplines. The difficult communication involved regarding the estimation and treatment of identified risks needs to be supported by a number of complementary approaches, including education, a dedicated internal culture of collaboration and, possibly, IT tools, which could use graphical modelling. This paper focuses on how such an interdisciplinary legal risk assessment could be supported through graphical modelling as an element of a future IT-tool support for legal risk management.

4.

Requirements to visualisation ^

The graphical language should be as simple as possible, while at the same time ensuring that all necessary conceptual elements of legal risk can be adequately modelled. I have selected the risk-related concepts I consider necessary from the draft ISO risk management vocabulary, in combination with some concepts selected from legal theory. According to the draft ISO risk management vocabulary, risk is defined as the «effect of uncertainty on objectives.»5 In order to assess risk, we thus need to analyze uncertainty, which in our context includes legal uncertainty and factual uncertainty. Uncertainty is in this context defined as the «state, even partial, of deficiency of information related to or understanding or knowledge of an event , its consequence, or likelihood.»6 By event, the ISO refers to the «occurrence or change of a particular set of circumstances.»7 The term risk source can be used for «anything, which alone or in combination has the intrinsic potential to give rise to risk.»8 In legal risk management, we need to distinguish between two types of risk sources: legal rules and facts. Legal rule is a binding normative proposition. A legal rule is expressed and described in a normative proposition. Facts are simply the circumstances of the case, meaning, anything that is not a legal rule. Facts are described in a proposition about facts. This conceptual framework can be reduced to the following elements:9

- Facts: Circumstances;

- A proposition about facts;

- Uncertainty about facts, expressed in a likelihood estimate;

- Effect: The effect on the stakeholder’s objectives;

- Effect description;

- Affected objective(s);

- Risk value;

- Likelihood value;

- Consequence value;

- Norms:

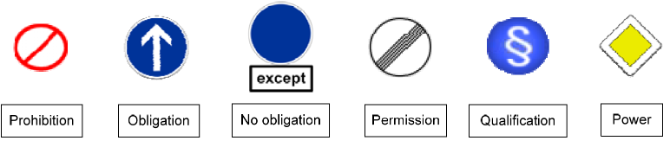

- Normative proposition, which can be of the following modality;10

- Obligation;

- No obligation (privilege);

- Permission;

- Prohibition;

- Legal power;

- Legal qualification;

- Legal source, on which the legal norm is based;

- Legal uncertainty:

- Qualitative statement about what is uncertain, or

- Likelihood estimate.

- Normative proposition, which can be of the following modality;10

5.

Visualisation ^

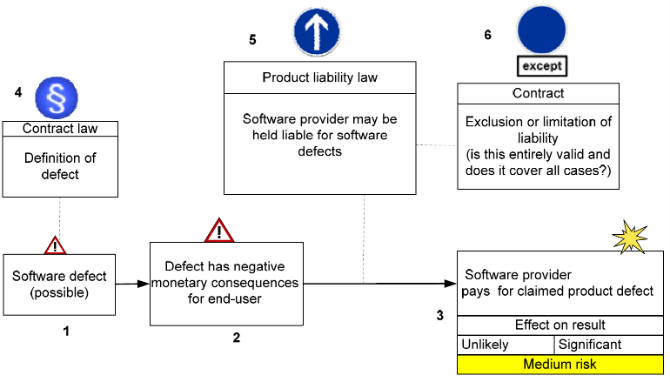

The graphical approach consists of a combination of two approaches. First, the visualisation of (factual) risk is based on an adaptation of an existing graphical language for risk analysis.11 This is illustrated in Figure 1, which consists of two boxes connected by an arrow. In graph theory, such «boxes» would be referred to as vertices. The vertices in this graph are numbered to facilitate the explanation. The graphical language consists of syntax and a semantics, both of which can only be superficially presented here. The diagram is read as follows: The fact (1) «Software defect» may lead to the fact (2) «Defect software has negative effect on end-user.» The latter may in turn lead to the effect (3) «Software provider pays for claimed product defect.» This could have an effect on SAP’s result. Such an effect is unlikely, but could be significant. We would have to assume that «unlikely» and «significant» have a well-defined meaning in the analysis, which allows us to conclude that this is a medium risk. The likelihood estimate partly depends on the likelihood of the facts that lead to the event. In this case, the software defect is marked as «unlikely.» The total risk value «medium» is also visible through the yellow shading at the bottom of the third vertex, which probably will not be shown in the printed version of this paper. The yellow colour is used to distinguish it from low risks (green) and high risks (red). The use of colours is intended to facilitate a prioritisation of risks, where higher risks deserve more attention. This can only be insufficiently appreciated in this simple example, in which only one risk is visualized.

The above figure only visualises facts, and does not yet include the visualisation of norms. In order to add legal aspects to the model, we would need to introduce dedicated icons to indicate a normative content. I propose to use the icons shown below, based on road traffic signs, to visualize the types of norms (their normative modality). Road traffic signs offer a universal visual semiotics,12 and the some of the categories of signs defined by Annexe 1 of the Vienna Convention on Road Signs and Signals (1968) broadly correspond to some of the categories of norms discussed in legal logic and legal theory.13 Based on this theoretical foundation, we should be able to visualise any legal issue with the help of these icons. Obviously, the icons need to be combined with an appropriate textual notation, because the icons themselves do not carry sufficient meaning to determine what is forbidden, obligated, etc. The textual notation could also include the norm addressee, if any, and the conditions under which the norm applies. Moreover, the legal risk assessment could require a textual expression of the legal uncertainty related to the normative proposition in the modelled context.

Figure 3 below contains a possible visualisation of the example presented at the beginning of this paper. In addition to a more comprehensive view of the facts of the case (vertices 1-3), the model includes some normative propositions that apply to these facts (vertices 4-6). The norm application is illustrated by a dotted line that connects to the modelled facts or to the arrows. An example of the former is the software defect (1), since the term «defect» may have a particular meaning in contract law (vertex 4, a legal qualification). In the context of vertex 5, the norm explains the reason for why the fact leads to the consequence.14

The relation between vertices 5 and 6 illustrates how norms may apply to each other. The obligation to pay for software defects (5) may be excluded by the limitation of liability in SAP’s contracts (6). However, importantly, there is an uncertainty about the validity of such exclusions. This legal uncertainty is expressed in the parentheses below the normative proposition (shown at the bottom of vertex 6). Thus, both the uncertainty of facts (vertex 1) and legal uncertainty (vertex 6) are included within a single diagram.

6.

Concluding remarks ^

It is intended for this paper to offer an initial idea of what this approach to visualisation can achieve. Further work will need to describe additional details and report some of the results from applying this approach in practice.

7.

References ^

Eckhoff, Torstein, and Nils Kristian Sundby. Rechtssysteme: Eine systemtheoretische Einführung in die Rechtstheorie. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1988.

Freeman, James B. Dialectics and the macrostructure of arguments a theory of argument structure, Studies of argumentation in pragmatics and discourse analysis 10. Berlin: Foris Publications, 1991.

ISO. «Committee Draft 2 for Risk management – Vocabulary.» Geneva: ISO, 2008.

Mahler, Tobias. «Defining Legal Risk.» In Corporate Contracting Capabilities: Conference proceedings and other writings, edited by Solili Nystén-Haarala, 51-76. Joensuu: University of Joensuu Publications in Law, 2008a.

Mahler, Tobias. «Tool-supported legal risk management: A roadmap.» Paper presented at the «The future of ...» Conference on law and technology, Florence 2008b.

SAP. «IFRS FINANCIAL REPORTS.» Walldorf, 2007.

Sartor, Giovanni. Legal reasoning: A cognitive approach to the law. Berlin: Springer, 2005.

Toulmin, S.E. The Uses of Argument: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Vraalsen, Fredrik, Tobias Mahler, Mass Soldal Lund, Ida Hogganvik, Folker den Braber, and Ketil Stølen. «Assessing Enterprise Risk Level: The CORAS Approach.» In Advances in Enterprise Information Technology Security, edited by Djamel Khadraoui and Francine Herrmann, 311-33. Hershey, New York: Information Science Reference, 2007.

Wagner, Anne. «The rules of the road, a universal visual semiotics.» International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 19, no. 3 (2006): 311-24.

Tobias Mahler, Norwegian Research Center for Computers and Law (NRCCL), University of Oslo, NO

tobias.mahler@jus.uio.no

- 1 Mahler, 2008b.

- 2 Mahler, 2008a.

- 3 SAP, 2007, p. 56.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 ISO, 2008, definition 3.1.

- 6 Ibid, definition 3.3.5.1.

- 7 Ibid, definition 3.3.4.2.

- 8 Ibid, definition 3.3.4.1.

- 9 Due to space limitations, this paper omits the visualisation of treatments, i.e. of measures that may be employed to mitigate the risk.

- 10 These normative modalities are directly based on Chapters 4 and 5 in Eckhoff and Sundby, 1988.

- 11 Regarding the CORAS language, see, e.g., Vraalsen, et al., 2007.

- 12 Wagner, 2006.

- 13 See above, note 10. Regarding a similar, but more sophisticated approach in legal logic, see, e.g. Sartor, 2005 Obviously, the my visual approach needs to imply a gross simplification of Sartor’s detailed theory. The four deontic notions of prohibition, obligation, no obligation, and permission are addressed in Sartor’s Chapter 17. The notion of power is by Sartor referred to by Sartor as «protestative concepts» treated which are addressed in Chapter 22. The notion of legal qualification is similar to normative conditionals, addressed by Sartor in Chapter 21.

- 14 This part of the notation, in which a norm explains why a fact leads to an effect, is inspired by Toulmin’s diagrams for argument modelling (see Toulmin, 2003; Freeman, 1991).