1.

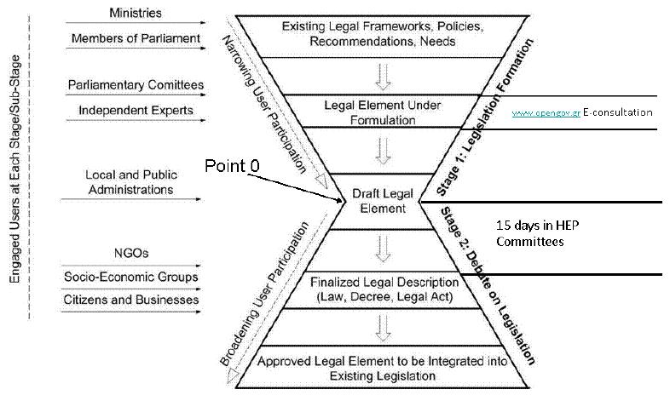

The background: the legislative process in Greece ^

2.

E-democracy: the recent evolution ^

In parallel, thanks to the last evolutions in the Web and especially in the Social Networks, we have witnessed a historical transition to a new era of collaboration, interaction, sharing and networked intelligence. The advent of social networks provides new avenues for influence2 and eventually opens up new perspectives for policy makers by using crowdsourcing to enlarge and enhance policy-advisory processes, policy making, and policy feedback3.

Taking into account the last Digital Agenda 2020 and Policy Making 3.0, the participatory and evidence-based model used by Digital Futures5, stakeholders and policy makers form a social network to co-design policies on the basis of the metaphor of «collective brain» (or emergent collective intelligence) with two distinct factors:

- The scientific evidence stemming from the collective wisdom of stakeholders and policy makers. This is the collective «rational» contribution of the participants to the policy (or the «left brain» of the social network). Evidence is often elicited from data and numerical models of the real world (e.g., statistics, data mining).

- The sentiment stemming from the collective aspirations of stakeholders and policy makers, identifiable or even measurable through the social network. This can be considered the «emotional» contribution of the network participants to the policy (or the «right brain» of the social network).

3.

Moderated or non-moderated discussions in Social Networks ^

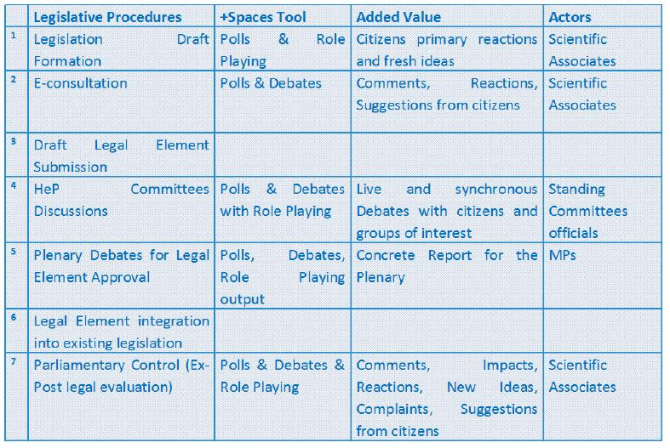

The lessons learnt from the +Spaces pilots implemented for the Hellenic Parliament were:

- Through the +Spaces platform it was possible to address several public groups on different stages of the policy making process

- +Spaces was able to support policy makers» presence in Social Networks

- Advanced role-playing simulation creating fresh ideas for policy makers

- Data analysis with graphs, sentiment clusters, highlights and citizens» reputation scores provides a clear and short overview of the policy discussion

- Policy makers were enabled to post simple questions in polls, brief policy descriptions and a couple of statements for debates to get feedback from citizens

- 3D & 2D role-playing or 3D debates are something new with a touch of innovation, looking like a brainstorming game or a place where fresh ideas are born

- The +Spaces platform could be used as a policy marketing tool

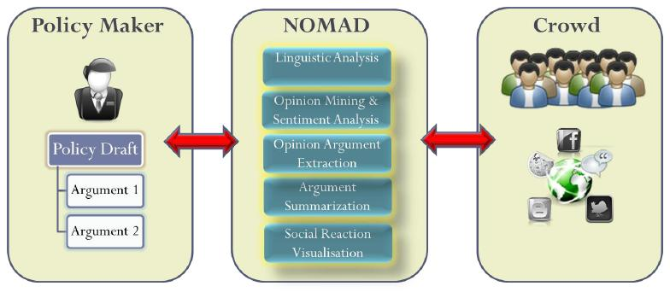

The EC FP7 project NOMAD (Policy formulation & validation through non-moderated crowdsourcing7), on the other hand, will provide policy makers with fully automated solutions for content search, acquisition, categorisation and visualisation that work in a collaborative form in the policy-making arena. Thereby, the policy makers could monitor social media discourses and listen to the citizens, gather feedback to the draft policy making agenda as well as the draft policies, obtain inputs to the policy making process by collecting opinions, arguments, and sentiments, visualize and analyse the non-moderated «wisdom of crowds’8, while collaborating, if possible, with the citizens at a later stage.

The NOMAD project started in 2012, with identifying the user requirements. The initial outcomes are the following:

- Policy makers deem it important to get access to the current policy related discussions in the social media

- Currently, it is difficult to receive all reactions to draft policies properly displayed for an effective use

- Feedback to the discourses in the policy making arena, and particularly in Parliament, was to be obtained in real time, based on citizens» reactions in the social media

- However, policy makers would not be able to initiate a communicative intercourse with the citizens by only using the «wisdom of crowds» from the social media

4.

Conclusions ^

Real-life experience has proved there are many unsolved challenges in policy making, which restrain policy makers from providing sustainable and inclusive decisions and citizens from getting engaged in policy discussions. Public policy issues are not always appealing, and citizens fail to understand the relevance of the issues and to see «what’s in it for me», which would be reflected in a decline in the voters» turnout and a lack of trust in politicians that is shown by opinion polls. While the Internet has long promised an opportunity for widespread involvement, e-participation initiatives often struggle to generate active and regular participation9, and there is a huge gap between the technological advancements and the everyday active participation of citizens in the policy-making processes. Previous research projects (like, e.g., LEX-IS or VoiceS) and their pilots were mostly dedicated to closed groups of users (up to 200 in most cases) but failed to involve the public at large.

The lack of comprehensible and down-to-earth visualizations for easing out the complexity in policy decisions, the under-performance of existing policy models in conjunction with simulation mechanisms, and the insufficient use of the huge amounts of data that are available on the web, are among the important issues that need to be tackled in order to take the leap forward in policy making. Therefore, ICT tools still have untapped potential and remain a «novelty» for the majority of government systems, despite their already acknowledged benefits in their application by governments related to the quality and speed of policy making, as well as to evidence-based policy decision making10.

When comparing, from the point of view of policy making support, the options of non-moderated crowdsourcing, on the one hand, and moderated discourse, in the other hand, and their feasibility, one will have to differentiate between the various stages of the policy cycle:

- At the initial stage of political agenda setting, it will be necessary to identify societal requests for new policies and policy changes as early as possible, and within a scope as broad as possible. Thus, any kind of moderation might already narrow the scope of debate, so that this seems to be the stage of the policy cycle most appropriate to be supported by non-moderated crowdsourcing. The free flow of public discourse within civil society, as mirrored in the social media, is to be analyzed, and all subjects of pertinence to the policy making agenda, along with the yet rough opinions of the members of civil society on what directions to follow in these issues, are to be extracted.

- Once the political agenda, in a mid-term range, has been set, it is up to the main actors of the political system, i.e. the political parties that have the task to aggregate societal positions, but in some cases also the major interest groups, to prepare concrete policy proposals to tackle the issues put on the agenda. At this stage, moderated debates already make more sense, because there is already a limited number of alternative policy options to be put to a debate that has to be formally initiated by the actors of the political system. Nonetheless, there still may be some risk that some fundamental option has not yet been identified, so that the crowdsourcing approach will be a valuable supplement to moderated debate, in particular as long as the political system has not been successful in engaging larger numbers of the members of civil society in such moderated debates. One major argument against formalized public consultation at the policy formulating stage comes from the experience that such a procedure might be used by small groups of activists, i.e. citizens showing an engagement far above the ordinary for a particular issue, to dominate the debate, and strain the outcome. Such effect indeed may be balanced by a complementary crowdsourcing approach.

- Once the basic policy decision, i.e. the political (usually not yet normative) decision on the objectives to be followed and the means to be applied for that purpose, has been made, the policy regularly is transposed into a draft normative act, mostly a draft bill, which in the majority of cases is done by the legislative experts in the competent government agencies. Such draft bills in most normative systems are put to a formal consultation procedure, which would anyway include the main stakeholders but sometimes also the general public. Commenting on draft bills would require some expertise in legislative drafting techniques as well as in the substantive matter to be regulated. Thus, this usually would be a stage of well-structured expert debate, with the general public continuing to reflect on the general policy directions, which reflections however would be of decreasing influence, for the basic directions already having been defined. Non-moderated crowdsourcing therefore will play a minor role at this stage.

- The latter in principle would also apply to the stage of parliamentary decision-making. At this stage, the finishing is done on the draft legal acts, but because it is done in a transparent way civil society will reflect on it more intensively again. Thus, even though a major change in the policy direction is unlikely to happen at this late and final stage in the legislative process, there is a vivid interest by the political decision-makers in learning about these public reactions, which would challenge their communicative capacity to be displayed in the parliamentary arena. Non-moderated crowdsourcing, therefore, is an important option again, in this concluding phase of law-making, because it would give the MPs important hints about how to explain the decision made to the public (or, from the point of view of parliamentary opposition, how to argue against it).

- Finally, the adopted and promulgated law is to be implemented. This process will not only be monitored by the MPs but also, in an informal way, by civil society. Establishing feedback cycles therefore is an important means to enable the actors of the political system to analyze the impact of legal measures and distinguish between possible lackings in the implementation of the regulations adopted and lackings in the regulations themselves. Identifying lackings of the latter kind will prompt a new policy cycle. Since this monitoring requires a wide and open focus on a policy field, crowdsourcing seems to be an appropriate approach again.

Dimitris Koryzis, Head of department, Hellenic Parliament, European Programs Implementation Service.

Fotis Fitsilis, Hellenic Parliament, Scientific Service.

Günther Schefbeck, Head of department, Austrian Parliamentary Administration, department «Parliamentary Documentation, Archives, and Statistics».

- 1 Charalabidis, Yannis/Lampathaki, Fenareti/Misuraca, Gianluca/Osimo, David (2012), ICT for Governance and Policy Modelling: Research Challenges and Future Prospects in Europe, in: Proceedings of the 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Hawaii, pp.2472-2481.

- 2 Christakis, Nicholas/Fowler, James (2010), Connected: The Amazing Power of Social Networks and How they Shape our Lives, London.

- 3 Nam, Taewoo (2012), Suggesting frameworks of citizen-sourcing via Government 2.0, in: Government Information Quarterly, 29(1), pp. 12-20.

- 4 Bertot, John C./Jaeger, Paul T./Grimes, Justin M. (2010), Using ICTs to create a culture of transparency: E-government and social media as openness and anti-corruption tools for societies, in: Government Information Quarterly, 27(3), pp. 264-271, http://www.milthailand.org/phocadownload/2011_Files/11_Nov/transpareny%20government.pdf.

- 5 https://ec.europa.eu/digital-agenda/en/policy-making-30-0.

- 6 http://www.positivespaces.eu.

- 7 http://www.nomad-project.eu.

- 8 Surowiecki, James (2004), The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations, London.

- 9 Crossover (2012), International Research Roadmap on ICT Tools for Governance and Policy Modelling, Interim Version, http://crossover-project.eu/Portals/0/Material/0204F01%20International%20Research%20Roadmap%20on% 20ICT%20Tools%20for%20Governance%20and%20Policy%20Modelling.pdf last accessed 30.1.2013.

- 10 Charalabidis, Yannis/Lampathaki, Fenareti/Askounis, Dimitris (eds.) (2012), Paving the Way for Future Research in ICT for Governance and Policy Modelling, Nea Kifisia.