1.

Introduction ^

2.

Relational law ^

Let’s start with the following example, posted in a blog on contract law by Nancy Kim:

Which brings me to relational contract law. The purpose of these companies is to enable the musician to survive (and even thrive) without being backed by a record company. Now, the musician can directly manage the relationship with the fan. In the past, a fan joined a fan club, bought a ticket to a concert from one vendor, a record from a retailer, a tee shirt from another retailer ―you get the picture. With the exception of the rules on the back of the concert ticket and the fan club membership rules, the other transactions were not governed by contract. The fan can now buy everything she or he wants that’s band-related from that band’s website, subject to the terms and conditions of the website and the licenses that accompany the digital products. Shouldn’t the terms of those contracts be considered in light of the existing relationship between the musician and the fan? Wouldn’t a relational contracts approach be helpful in analyzing the terms and how they should be interpreted and enforced?»1

Relational is a common property that emerges from the existing social and economic bonds among companies, providers, customers, consumers, citizens (or digital neighbors).2 However, it seems to be a pervasive quality, perhaps straddling too many genres and fields, from psychology to jurisprudence, and from political science to business managing and marketing studies. «Relational» has been applied not only to contracts but to sovereignty3, rights4, copyright5, governance6, norms7, and conflicts8, broadening up the field from private law to the public domain, and from anthropological «relational lens»9 to political «responsive regulation».10 Relational refers to the capacity to set up a common space of mutual relations ―a shared regulatory framework― in which some reciprocity is expected with regard to goods, services, attitudes and actions. Thus, relational law is more based on trust and dialogue than on the enactment of formal procedures or on the enforcement of sanctions.11

But this is not to say that a single specific domain may be sufficient to define the dimensions and layers of relational law. On the contrary, interestingly enough, since the beginning the relational perspective emerged from the interplay between lawyering practices, contract studies, and socio-legal scholarship, alike. Both Stewart Macauley (1963) and Ian R. Macneil (1985) viewed contracts as relations rather than as discrete transactions looking at the evolving dynamics of the different players and stakeholders within their living constructed shared contexts. The notion of «relational thinking» emphasizes the complex patterns of human interaction informing all exchanges (MacNeil, 1985). But this in fact does not disregard a more conventional notion of what law is or how lawyers think12. More recent studies confirm that there is no simple opposition or alternate choice, but different combinations in between: legal contracting and regulatory governance may intertwine, substitute each other, or co-apply.13

3.

Regulatory systems and relational justice ^

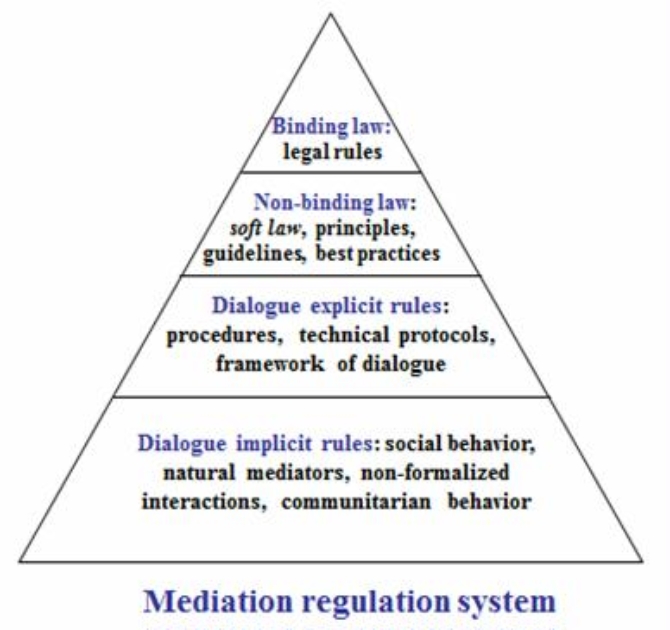

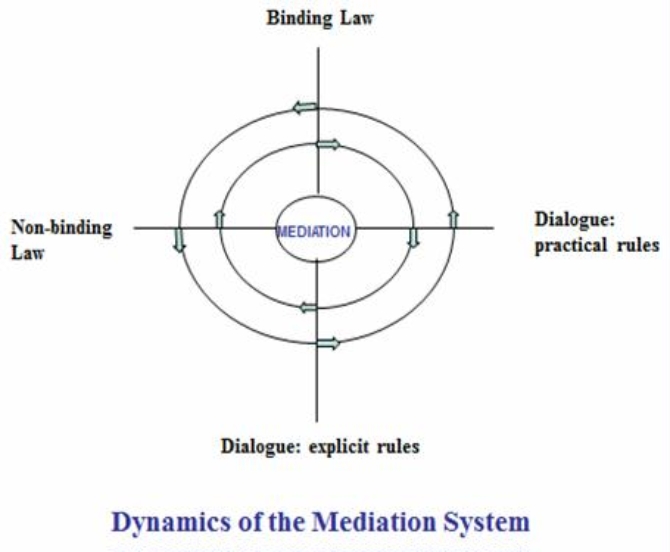

Regulatory systems are broader than their legal side because they include all aspects set by players in the social, political and economic games at stake.14 They are situated, flow-driven, and work specifically in a multitude of similar but different evolving scenarios. They usually have a formal, explicit side and an implicit, tacit one. Information and knowledge management and coordination constitute additional important features too, as they often require a set of steps to be followed and certain sort of actions to be taken. As long as they contain procedural ways to solve and manage conflicts as well, they shape relational systems of justice.15

In Artificial Intelligence, agreement and all the processes and mechanisms involved in reaching agreements through negotiation and dialogue between different kind of agents (human and non-human) are also a subject of research and analysis (Sierra et al. 2013). Interactions, transactions and the different procedural means to perform them is the subject of Agreement Technologies (AT).

4.

Regulatory Models and Social Intelligence Modeling ^

Recent work by Cristiano Castelfranchi, Carles Sierra, Enric Plaza, Pablo Noriega, Julian Padget, Marc d’Inverno, and many others, contribute to shape this view of a social mind which is not a mere aggregate of individual abilities, but a set of social affordances. Therefore, «social interactions organize, coordinate, and specialize as artifacts, tools; […] and these tools are not only for coordination but for achieving something, for some outcome (goal/function), for a collective work. [….]. We have to revise the behavioristic view of ‹scripts› and ‹roles›; when we play a role we wear a mind» (Castelfranchi, 2013).

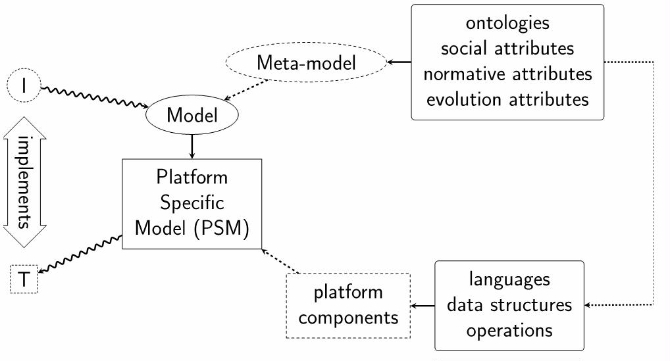

Let’s go back to the relation between AT, SI, institutions, and fundamental legal concepts. In this kind of social institutions, validity is not equivalent to legality23, and a technical system (i.e. a Multi-Agent System, MAS) has to be designed as a set of tools to comply with empirical requirements in a specific meta-model. Fig. 2 summarizes a general structure for such a meta-model. I stands for «Institution», T stands for «Technology», and PSM for «Platform Specific Model» (Noriega and d’Inverno, 2014).

- Regulatory system: a set of coordinated, individual, and collective complex behavior which can be grasped through rules, values and principles which constitute the social framework of the law.

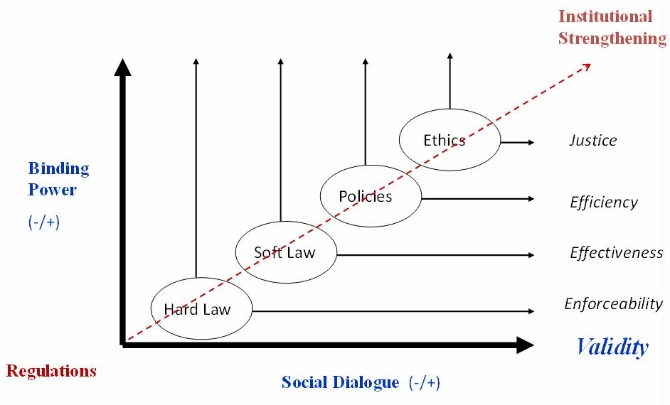

- Regulatory model: a regulatory system design, in which hard law, soft law, policies, and ethics can be combined (or mixed up) in different degrees in a set of explicit or implicit guidelines for the interoperability of systems and the inter-communication and coordination of agents.

- Validity can be conceptually defined as a second-order property, a four-tuple function of ethics (justice), policies (efficiency), soft law (effectiveness) and hard law (enforceability), fostering the application of metrics to measure institutional strengthening, i.e. the coordinated organization of components in specific platforms applying semantic technologies (among others).

5.

Crowdsourcing, legal crowdsourcing, and crowdservicing ^

The term crowdsourcing was first introduced by Jeff Howe in 2006 to refer to «the act of taking a job traditionally performed by a designated agent (usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an undefined, generally large group of people in the form of an open call»25. Different types have been already distinguished in the literature.26 But most of the more successful examples, like the Wikipedia or Twitter, may be defined as non-profit collective aggregation of information stemming from micro-tasks widely distributed across the Web, and freely performed by people. Therefore, it implies much more than a new way to recollect information or to respond to labor offers or contests, following the Amazon Mechanical Turk or Microworks.com models.

The broad democratic political model to be implemented cannot be taken for granted. It does not exist yet, as the integration between the regulatory forms of law, relational governance and what Charles Petrie (2008, 2010) called Emerging Collectivities (EC) has to be thought on new basis.

The challenge lies on the technological empowerment that the next steps of the Semantic Web, mobile technologies, grid computation, cloud computing, visualization technologies, geo-localization, and agreement technologies are able to bring to people involved in regulatory systems, and the way they can get profit and take advantage of them. Crowdsourcing can be expanded into crowdservicing (Davies, 2011).28 It is close to ubiquitous computing and human computing (Das and Vucovic, 2011), and it grounds and fosters emergency responses, crisis and disaster management, conflict resolution mechanisms (ODR), democratic transparency, and the organization of legal distributed knowledge through an easier access to law, constitutional reforms, and political participation.29

6.

References ^

Akçora, C.G. (2010): Using microblogs for crowdsourcing and public opinion mining, Ann Arbor MI: UMI Dissertation Publishing 1482188.

Blois, K.J.; Ivens, B.S. (2006): «Measuring relational norms: some methodological issues», European Journal of Marketing, 40 (3/4): 352–365.

Braithwaite, J. (2011). «The Essence of Responsive Regulation». UBC Law Review 44, 475–520.

Braithwhite, J. (2013). «Relational Republican Regulation», Regulation and Governance, 7 (1): 124–144.

Campbell, D. (2004): «Ian Macneil and the relational Theory of Contract», CDAMS Discussion paper 04/1E, March, 83 pp.

Casanovas, P. (2010). «Legal Electronic Institutions and ONTOMEDIA: Dialogue, Inventio, and Relational Justice Scenarios», in P. Casanovas et al. (Eds.), AICOL Workshops 2009, LNAI 6237, Springer Verlag, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, pp. 184–204.

Casanovas, P. (2012). «A note on validity and regulatory systems», Quaderns de filosofia i ciència, 42: 29–40.

Casanovas, P. (2013a). «Agreement and Relational Justice: A Perspective from Philosophy and Sociology of Law», in S. Ossowski (Ed.) Agreement Technologies, LGTS, Springer Verlag, Dordrecht, Heidelberg, pp. 17–41.

Casanovas, P. (2013b). «Legal Crowsourcing and Relational Law. What the Semantic Web Can Do for Legal Education», Journal of Australian Law Teachers Association vo. 5, 1 & 2, 2012, 159–176.

Casanovas, P.; Poblet, M. (2008). «Concepts and Fields of relational Justice», in P. Casanovas et al. (Eds.), Computable Models of the Law (LNAI 4884), Springer Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 323–339.

Casanovas, P.; Poblet, M.; López-Cobo J.M. (2011). «Relational Justice: Mediation and ODR through the World Wide Web», ARSP-Beiheft 131: 146–157.

Castelfranchi, C. (2013). «Minds as Social Institutions», Phenomenology and Cognitive Science DOI 10.1007/s11097-013-9324-0.

Ciambra, A.; Casanovas, P. (2013). «A composite indicator of validity for regulatory models and legal systems», AICOL-2013, Joint Workshop with SINTELNET, Bologna, December 11th, at JURIX-2013.

Claro, D.; Hagelaar, G.; Omta, O. (2003). «The determinants of relational governance and performance: How to manage business relationships?», Industrial Marketing Management 32: 703–716.

Craig, C.J. (2011): Copyright, Communication and Culture : Towards a Relational Theory of Copyright Law, Mass. (USA), Cheltenham (UK): Edward Elgar Publishing.

Chelariu, C.; Sangtani, V. (2009). «Relational Governance in B2B Electronic Marketplaces: an Updated Typology», Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 24 (2): 108–118.

Davies, J.G. (2011). «From Crowdsourcing to Crowdservicing», IEEE Internet Computing, May/June, 92–96.

Das, R.; Vukovic, M. (2011). «Emerging Theories and Models of Human Computation Systems: A Brief Survey», UbiCrowd’11, September 18, Beijing, China, ACM.

Fisher, T.; Huber, T.; Dibbern, J. (2011). «Contractual and Relational Governance as Substitutes and Complements – Explaining the Development of Different Relationships», ECIS 2011 Proceedings. Paper 67. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2011/67

Geiger, D.; Seedorf, S.; Schulze, T.; Nickerson, R. (2011): Managing the Crowd: Towards a Taxonomy of Crowdsourcing Processes, AMCIS-Proceedings of the Seventeenth Americas Conference on Information Systems, Detroit, Michigan August 4th-7th 2011.

Hunt, M.E; Ellison, M.M;Townes, Emilie M;Cheng, Patrick S;et al (2004). Round Table Discussion, «Same-sex Marriage and Relational Justice», Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion; 20 (2): 83–117.

Johar, G.V. (2005): «The Price of Friendship: When, Why, and How Relational Norms Guide Social Exchange Behavior», Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15 (1): 22–27.

Lederach, J.P, (1997). Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Lederach, J-P. (2005). The Moral Imagination. The Art and Soul of making peace, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ludsin, H. (2008). «Relational Rights Masquerading as Individual Rights», Duke Journal of Gender Law & Policy, 15, 195–221.

Macauley, S. (1963). «Non-Contractual Relations in Business: A Preliminary Study», American Sociological Review, 28: 55–67.

Macneil, I.R. (1974). «The Many Futures of Contract», Southern California Law Review, 47: 691–896.

Macneil, I.R. (1985). «Relational contract: what we do and do not know», Wisconsin Law Review, 3 (3): 483–525.

Minow, M.; Shandley, M.L. (1996). «Relational Rights and Responsibilities: Revisioning the Family in Liberal Political Theory and Law», Hypathia. Journal of Feminist Philosophy, 11 (1): 4–29.

Nedelsky, J. (2011). Law’s Relations: A Relational Theory of Self, Autonomy, and Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Noriega, P.; d’Inverno, M. (2014). «Crowd-Based Socio-Cognitive Systems», paper presented at the SINTELNET Workshop, Crowd-Intelligence, Barcelona, IEC, 8–9 January 2014.

Ossowski, S., C. Sierra, and V. Botti (2013). «Agreement technologies – A computing perspective», in S. Ossowski (Ed.) Agreement Technologies, LGTS, SpringerVerlag, pp. 3–16.

Ott, C.M.; Ivens, B.S. (2009). «Revisiting the Norm Concept in Relational Governance», Industrial Marketing Management 38: 577–583.

Petrie, C. (2008). «Collective Work», IEEE Internet Computing, March/April: 93–95.

Petrie, C. (2010). «Plenty of Room Outside the Firm», IEEE Internet Computing, March/April, 92–95.

Poblet, M. (2013). «Visualizing the law: crisis mapping as an open tool for legal practice», Journal of Open Access to Law 1 (1) http://ojs.law.cornell.edu/index.php/joal/article/view/12

Poblet, M.; García-Cuesta, E.; Casanovas, P. (2013). «Crowdsourcing Tools for Disaster Management: A Review of Platforms and Methods», AICOL-2013, Joint Workshop with SINTELNET, Bologna, December 11th, at JURIX-2013.

Poppo, L.; Zenger, Todd (2002). «Do Formal Contracts and Relational Governance Function as Substitutes or Complements?», Strategic Management Journal 23: 707–725.

Ross, R. (2010). Exploring criminal justice and the Aboriginal paradigm. Upper Law Society of Canada. http://www.lsuc.on.ca/media/third_colloquium_rupert_ross.pdf

Stacey, H. (2003). «Relational Sovereignty», Stanford Law Review, 55 (5) (May): 2029–2059.

Vieille, S. (2012). Mãori Customary Law: A Relational Approach to Justice. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 3 (1). http://ir.lib.uwo.ca/iipj/vol3/iss1/4

Wallenburg, C.M..; Raue, J.S. (2011). «Conflict and its governance in horizontal cooperations of logistics service providers», International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 41 (4): 385–400.

Wielsch, D. (2013) «Relational Justice», Law and Contemporary Problems 2: 191-211.

Zheng, J.; Roehrich, J.K.; Lewis, M.A.. (2008). «The dynamics of contractual and relational governance: Evidence from long-term public–private procurement arrangements», Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 14: 43–54.

Pompeu Casanovas, Institute of Law and Technology (IDT), Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- 1 Nancy Kim, «Relational contracts and new business models», posted November 9th, 2011 at http://lawprofessors.typepad.com/contractsprof_blog/2011/11/relational-contracts-and-the-digital-age.html (consulted January 30th 2012).

- 2 I summarize in this point the explanation provided in Casanovas (2013a).

- 3 Stacey (2003).

- 4 Minow and Shandley (1996); Ludsin (2006).

- 5 Craig (2011).

- 6 Zeng et al. (2008), Chelariu and Sagntani (2009)

- 7 Into consumer research studies: Johar (2005); in B2B relationships: Blois and Ivens (2006); in relational governance: Ott and Ivens (2009).

- 8 Wallenburg and Raue (2011).

- 9 Ross (2010), Vieille (2012).

- 10 Braithwhite (2011, 2013) conceives «responsive regulation» as a relational process among all stakeholders, including the community of researchers.

- 11 Following the well-trodden path from concrete and specific interpersonal framing to more universal values and principles, there is a contemporary move as well towards a general theory of law, covering all aspects of human beings as «relational selves» (Nedelsky, 2011).

- 12 «The relational contract dimensions important in our inquiry are first, the everyday working of exchange relations and transactions, or contract behavior (the behavioral dimension); second, the positive law of the sovereign relating to that behavior (the legal dimension); and third, legal scholarship relating to that behavior (the scholarly dimension).» (Macneil, 1985: 484). For a good comprehensive summary of Macneil’s work, see Campbell (2004).

- 13 Poppo and Zenger (2002); Fischer et al. (2011).

- 14 I have developed these ideas in Casanovas (2012, 2013).

- 15 See also Wielsch (2013: 198) «Legal reasoning must carefully identify all social references involved in a given case. Only when jurisprudence comes to recognize the full range of relations between rights and social orders does it actually observe the law as a system within an environment and enable the system as such to operate rationally. Only when the law takes into account all of the environmental references of a contract may it achieve a kind of ‹relational justice› that determines the relations between different social normativities in a responsible way. Relational justice takes seriously the independent normative claims of the social systems affected and their relatedness in a shared social environment.»

- 16 See Casanovas and Poblet (2008, 2009) for a more extensive treatment of Relational Justice (RJ), which we define broadly as a bottom-up justice, or the justice produced through cooperative behavior, agreement, negotiation or dialogue among actors in a post-conflict situation (the aftermath of private or public, tacit or explicit, peaceful or violent conflicts). The RJ field includes Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) and Online Dispute resolution (ODR), mediation, Victim-Offender Mediation (VOM), restorative justice (dialogue justice in criminal issues, for juvenile or adults), transitional justice (negotiated justice in the aftermath of violent conflicts in fragile, collapsed or failed states), community justice, family conferencing, and peace processes.

- 17 See about all these aspects, Lederach (1997, 2005).

- 18 http://www.llibreblancmediacio.com/.

- 19 DIRECTIVE 2008/52/EC OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 21 May 2008 on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters: «Article 3. Definitions: a. «Mediation» means a structured process, however named or referred to, whereby two or more parties to a dispute attempt by themselves, on a voluntary basis, to reach an agreement on the settlement of their dispute with the assistance of a mediator. This process may be initiated by the parties or suggested or ordered by a court or prescribed by the law of a Member State. b. «Mediator» means any third person who is asked to conduct a mediation in an effective, impartial and competent way, regardless of the denomination or profession of that third person in the Member State concerned and of the way in which the third person has been appointed or requested to conduct the mediation.» Cfr. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:136:0003:0008 (accessed January, 30th 2012).

- 20 More specifically: (i) the demographic and social transformation of the Catalan society (basically due to big immigration flows); (ii) the crisis of the jurisdictional model of the Administration of Justice (due to heavy caseloads and delays), (iii) the commitment of the European Union as regards the mechanisms of dialogue, governance and soft law in order to find a regulation model not exclusively built upon the traditional political and legal system of the State.

- 21 See a summary at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_intelligence.

- 22 See the European Network for Social Intelligence (SINTELNET), at http://www.sintelnet.eu/.

- 23 Casanovas (2012), Ciambra and Casanovas (2013).

- 24 CAPER is the acronym for «Collaborative information Acquisition, Processing, Exploitation, and Reporting for the prevention of organised crime», http://www.fp7-caper.eu/.

- 25 The rise of crowdsourcing, http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/14.06/crowds.html.

- 26 Geiger et al. (2011: 8) distinguish among different clusters of processes: (i) Integrative sourcing without remuneration (various forms of Wikis, user reviews, image tagging, or free user-generated content); (ii) selective sourcing without crowd assessment (private -contributors do not see each other’s contributions- and public design and innovation contests, in which one or a few winners are remunerated); (iii) selective sourcing with crowd assessment (contests that allow fellow contributors and other people to publicly assess individual contributions); (iv) integrative sourcing with success-based remuneration (used on store platforms that sell user-generated content -e.g., software, photographs, and designs- on the basis of profit sharing; (v) integrative sourcing with fixed remuneration (often applied to transactional tasks or micro-tasks, varying in complexity and often restricting the crowd of potential contributors).

- 27 See Akcora (2010:9): «Twitter has faced larger traffic during big events like Mumbai bombings in India or US elections. Such sporadic events boost Twitter traffic not only by exciting frequent ‹posters› to post more, but also by drawing ‹inactive› users back to the site to observe the event and contribute to it. In this sense, a user cannot be regarded lost, as is the case with other web sites, because her inactivity can end in the face of an event that draws her attention. Hence, account removals due to ‹inactivity› should not be performed in Twitter.»

- 28 «In my view, crowdservicing represents the full flowering of the augmentation concept [Engelbert]. Its technical infrastructure includes the evolving Internet and Web 3.0, emerging cloud computing platforms, Web-scale data management and semantic technologies, service-oriented computing, and Web services and their orchestration, computational agents, various interfaces to achieve programmatic access for availing crowd-based services, and diverse devices for user access.» (Davies, 2011: 94).

- 29 «Crisis mapping is a brand new field that has recently emerged as a set of online collaborative practices to source, process, and visualize information and data on events that derive from natural disasters (i.e. earthquakes, floods, tornados, or bushfires), crisis, and conflicts. Generally, the goal of crisis mapping is to provide aid organizations, NGOs, human rights activists, etc. with open, real time, geo-referenced, actionable data to organize a more efficient coordination and response. The mapping of the conflicts in Libya and Syria, to mention two recent examples, has allowed volunteers and technical communities (VTCs) to document human rights violations that can be the basis for legal prosecution of war criminals. Crowdsourced crisis mapping, therefore, opens a new era where global volunteer and technical communities may significantly contribute to transform international law by bringing into the picture a new humanitarianism based on practices, emerging norms, and both global and local capacities.» (Poblet, 2013). Cfr. Casanovas et al. (2011), Poblet et al. (2013), Casanovas (2012, 2013b). Cfr. also http://serendipolis.wordpress.com/.