1.

Introduction ^

There are approaches to improve the understandability of legal texts on various levels. Nevertheless, a comprehensive method to analyze and quantify the quality of legal texts is still missing. This paper is an attempt to quantify the complexity of legal texts (see Section 2). In particular, we analyze legal texts regarding textual vagueness. Thereby, it focusses on linguistic properties, indicating understandability and readability, in German and Austrian laws (see Section 2.3.). Section 3 explains the used research method in detail and introduces the used set of complexity indicating metrics (see Section 3.3. ) and the used dataset, existing of 3'553 German laws. The paper continues with an analysis of German laws (see Section 4). Based on a selection of legal texts, differences in understandability, vagueness and complexity regarding the metrics is shown (see Section 5). Because Austria and Germany share the same language and their legislations have several commonalities, we did a detailed analysis and comparison. Finally, we critically reflect our work (see Section 6), summarize the outcomes and sketch future research directions (see Section 7).

2.1.

Complexity Research for Legal Texts ^

2.2.

Vagueness in Legal Texts ^

Unveiling a words’ meaning is in general not a trivial task, especially not to algorithms. Depending on the particular word, humans can be very good at determining the meaning of a word in its context, nevertheless it requires a long learning phase. Although humans can determine the meaning behind the word «bank» easily, there are words, whose meaning cannot be determined easily, even if the context is known. A well-known concept in the legal domain are the so-called indeterminate legal terms1. Commonly, an adjective is used in combination with a noun, e.g. adequate waiting time (StGB, § 142). § 142 of the German criminal code regulates the required waiting of a person involved in an accident. Trivially, the legislation cannot provide a concrete number, specifying the minutes and hours to wait. This is because of the complex nature of the regulated area. § 142 of the criminal code was analyzed and different criteria contributing to the waiting time were identified, using prior judgments. Gerathewohl did a comprehensive analysis in 1987, and although he provided eleven criteria, e.g. daytime, place, damage, …, the determination of the waiting in particular cases remains complex (Gerathewohl 1987).

The phenomena of indeterminate, respectively vague words is well-studied in legal science and it is furthermore a basic and necessary concept in legislation. Hart describes it as the «open texture of law», whereas he argues for its necessity: «[…] the law must predominantly […] refer to classes of person, and to classes of acts, things and circumstances» (Hart, H. L. A 2012). Additionally, Hart states out, that law depends on the capability of language to express general rules, standards, and principles but cannot exclusively work by giving directives to each individual separately. Prior work shows that vagueness in legal language is indicated by vague words and terms (Bhatia et al. 2005; Mellinkoff 2004; Endicott 2000). In this paper, we are particularly interested in the vague words used within German acts and a possible classification of those (see Section 3.3.2.).

2.3.

Comparison of Acts ^

The comparison of legislations is an accepted method throughout legal sciences (Rusch 2006; Zweigert, Kötz 1996). Different sub-disciplines within the legal sciences, like criminal law and private law, use the comparison of legislations and laws as an additional information source. Based on this extended information basis. it is possible to gain additional insights into various legal domains, such as the style of judgments, the codification process, dependencies etc. Thereby the usage of the comparison of legislations as a method depends on the research interest. In this paper, we compare different but related acts, such as the act governing the liability for a defective product (orig. Produkthaftungsgesetz), regarding linguistic properties. In particular we are interested in the investigation of the laws regarding their vagueness and readability. Other approaches to compare legislations, respectively legal texts, focus on the so-called functional comparison, which aims to investigate differences regarding problems and their solutions in different legislations of countries and cultures (Rusch 2006). The functional aspect starts from an existing problem in society or economy and analyzes the differences and commonalities in the solutions that different countries have produced. Consequently, legal experts are performing these analyses and they have a strong focus on the different functionality of the solutions (Rusch 2006; Rösler 1999).

3.

Research Approach: Quantitative Analysis and Comparison ^

3.1.

Research Objectives ^

- How to objectively measure linguistic properties of laws, such as indeterminacy, vocabulary variety and readability?

- What are relevant linguistic properties extending the existing set of metrics to represent textual complexity of acts?

- Can complexity indicators be used to compare different but related acts of distinct legislations, e.g., Germany and Austria, on a linguistic and structural level?

3.2.

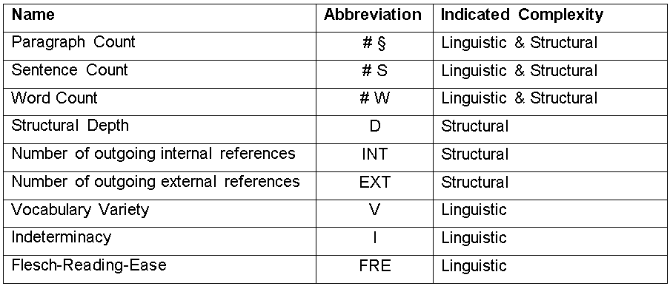

An Existing Set of Linguistic Metrics ^

3.3.

Extending the Existing Set of Metrics ^

Our research is based on the analysis of German laws, which we retrieved from the platform www.gesetze-im-internet.de hosted and maintained by the Federal Ministry of Justice, represented by Kompetenzzentrum Rechtsinformationssystem (CC-RIS). To run deeper analysis we imported all available laws into a local information system. At the importing date (13th June 2014), we imported 6'015 laws and regulations, which represent according to the platform «almost the complete and current federal law» (BMJ 2014). Since we are performing several algorithms we only considered those texts, with at least 200 words, leading to a dataset with 3'553 distinct legal texts.

3.3.1.

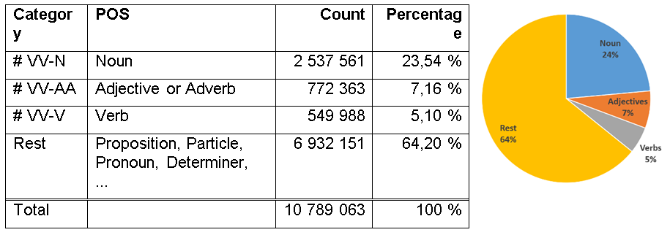

Vocabulary Variety ^

According to Ruoff et al. the frequency of nouns, adjectives, respectively adverbs, and verbs – if summed up – make about 44.88% of the parts of speech used in the German language (Ruoff 1981, pp. 19–26). Thereby nouns make 10.81%, verbs 21.19% and adjectives occur to 12.88% (adverbs included). The distribution was determined on 500’000 German words, which were classified manually. Based on this we counted the three parts of speech that are significantly contributing to the textual information (see Section 4.1.).

3.3.2.

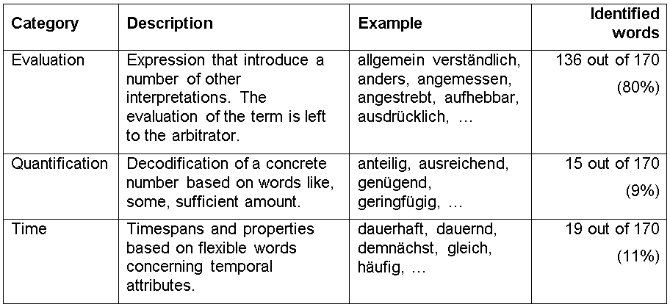

Indeterminacy ^

3.3.3.

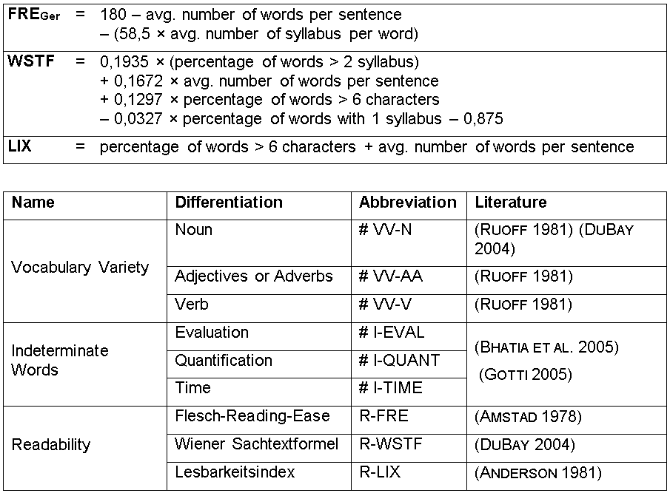

Readability ^

4.

Applying Metrics to German Laws ^

4.1.

Vocabulary Variety ^

4.2.

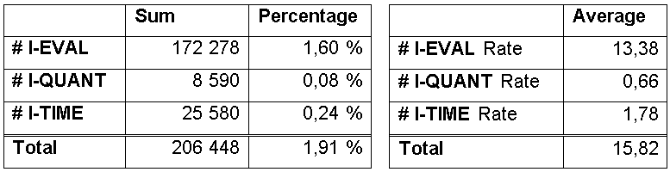

Indeterminate Words ^

4.3.

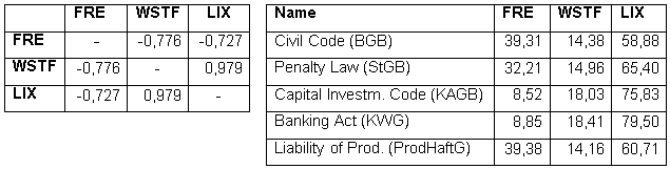

Readability ^

Table 6: Correlation between the used readability indexes and five exemplary laws and their readability

5.

Law Comparison regarding Metrics: Liability of Defective Products ^

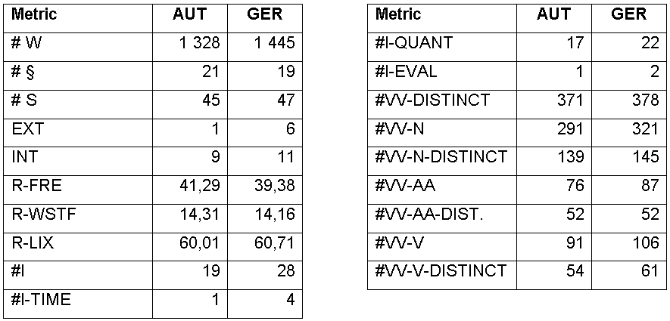

Using the proposed metrics, we analyzed two different but related laws from different countries. We considered the Austrian and the German act governing the liability for a defective product. The council regulation 85/374/EEC is the foundation for both laws. Table 7 shows the comparison of the two laws, regarding the derived metrics.

6.

Critical Reflection ^

7.

Conclusion and Outlook ^

The paper addresses linguistic phenomena on a large dataset, namely 3'553 German law texts. Thereby it uses quantitative linguistics to measure metrics indicating readability, indeterminacy and vocabulary variety. The metrics extend and existing set of metrics, representing legal complexity, and address properties of texts and their words with respect to vocabulary variety, indeterminacy, and readability. Furthermore, the paper uses the overall set of metrics to compare different but related acts, namely the liability for a defective product.

8.

Publication bibliography ^

StGB (23 April 2014): Strafgesetzbuch. Available online at http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/stgb/, checked on 11 November 2014.

Amstad, T. (1978): Wie verständlich sind unsere Zeitungen? Zürich: Studenten-Schreib-Service.

Anderson, Jonathan (1981): Analysing the Readability of English and Non-English Texts in the Classroom with Lix. In ERIC.

Bamberger, R.; Vanecek, E. (1984): Lesen-Verstehen-Lernen-Schreiben: die Schwierigkeitsstufen von Texten in deutscher Sprache: Jugend und Volk. Available online at http://books.google.de/books?id=TElTAAAACAAJ.

Bane, Max (2008): Quantifying and measuring morphological complexity. In Proceedings of the 26th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, pp. 69–76.

Best, Karl-Heinz (2006): Sind Wort- und Satzlänge brauchbare Kriterien der Lesbarkeit von Texten? In Sigurd Wichter, Albert Busch (Eds.): Wissenstransfer – Erfolgskontrolle und Rückmeldungen aus der Praxis. Band 5. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH, pp. 21–31.

Bhatia, Vijay; Engberg, Jan; Gotti, Maurizio; Heller, Dorothee (Eds.) (2005): Vagueness in Normative Texts. Berlin: Peter Lang GmbH (23).

BMJ (2014): Juris. Gesetze im Internet. Available online at http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/, checked on 22 July 2014.

Bourcier, Danièle; Mazzega, Pierre (2007): Toward measures of complexity in legal systems. In : ICAIL ‘07 Proceedings of the 11th international conference on Artificial intelligence and law.

Casanovas, Pompeu; Biasiotti, Maria Angela; Francesconi, Enrico; Sagri, Maria Teresa (Eds.) (2007): Proceedings of LOAIT ‘07. II Workshop on Legal Ontologies and Artificial Intelligence Techniques.

DuBay, William H. (2004): The Principles of Readability. Education Resources Information Center.

Endicott, Timothy A. O. (2000): Vagueness in Law: Oxford University Press.

Gerathewohl, Peter (1987): Erschließung unbestimmter Rechtsbegriffe mit Hilfe des Computers. Ein Versuch am Beispiel der angemessenen Wartezeit bei § 142 StGB. Dissertation. Eberhard-Karls-Universität, Tübingen.

Gotti, Maurizio (2005): Vagueness in the Model Law. In Vijay Bhatia, Jan Engberg, Maurizio Gotti, Dorothee Heller (Eds.): Vagueness in Normative Texts. Berlin: Peter Lang GmbH (23).

Hart, H. L. A (2012): The concept of law. Third edition (Clarendon law series).

Köhler, Reinhard (2005): Quantitative Linguistik. Berlin [u.a.]: De Gruyter (Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, 27).

Mellinkoff, D. (2004): The language of the law: Resource Publications.

Rösler, Hannes (1999): Rechtsvergleichung als Erkenntnisinstrument in Wissenschaft, Praxis und Ausbildung. In JuS – Juristische Schulung (11), pp. 1084–1086.

Ruoff, A. (1981): Häufigkeitswörterbuch gesprochener Sprache: gesondert nach Wortarten, alphabetisch, rückläufig alphabetisch und nach Häufigkeit geordnet: Niemeyer (Idiomatica Series).

Rusch, Arnold F. (2006): Methoden und Ziele der Rechtsvergleichung. In Jusletter (13). Available online at http://jusletter.weblaw.ch/juslissues/2006/362.html.

Schendera, Christian F. G. (2004): Die Verständlichkeit von Rechtstexten. In Kent D. Lerch (Ed.): Die Sprache des Rechts: Recht verstehen. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, pp. 321–373.

Schuck, Peter H. (1992): Legal complexity: some causes, consequences, and cures. In Duke Law Journal.

Waltl, Bernhard; Matthes, Florian (2014): Towards Measures of Complexity: Applying Structural and Linguistic Metrics to German Laws. In Jurix 2014: Legal Knowledge and Information Systems.

Bernhard Waltl, Research Associate, Technische Universität München, Department of Informatics, Software Engineering for Business Information System, Boltzmannstraße 3, 85748 Garching bei München, DE, b.waltl@tum.de; https://wwwmatthes.in.tum.de/

Florian Matthes, Professor, Technische Universität München, Department of Informatics, Software Engineering for Business Information Systems, Boltzmannstraße 3, 85748 Garching bei München, DE, matthes@in.tum.de; https://wwwmatthes.in.tum.de/

- 1 The German translation: «unbestimmte Rechtsbegriffe».