The development of rOWLer is part of the PhD thesis of the author2 and draws on experiences gained by modelling legal norms with Java and OWL 2. This research tries to fill the gap between the syntactical representation of norms (in XML or other formats) and the need of public administration for a powerful, yet easy to use and customizable legal rule engine. The architecture of rOWLer is aligned with the semantic web stack and is compatible with LegalRuleML [Athan et al. 2013], an upcoming standard for modelling legal rules. Present software solutions could be improved, following the theoretical models available.

1.1.

Motivation ^

2.

Architecture ^

The architecture of rOWLer consists of three main layers complemented by an electronic document repository, namely the process layer, the rule layer and the ontological layer. What follows is a short overview of the architectural layers of rOWLer, each providing a different view on law and legal rules.

- Process Layer: The process layer formalizes the legal procedure and is responsible to handle the dialogue between the applicant and the public agency. It collects the relevant facts by automatic and manual means and interacts with the rule layer to continuously provide preliminary results until the final decision. The authorizing person is asked by the system for decision if a «hard» rule should be applied.

- Rule Layer: This layer contains the formal rules and the inference engine. It drives legal reasoning by retrieving necessary information like facts from the ontology and providing results to the process layer above.

- Ontological Layer: The ontological layer supports the layers above by shallow reasoning on the knowledge base staying within OWL 2, preparing it for more complex reasoning using rules. Especially by data completion, reasoning on material circumstances (claims, facts and proofs) and legal concepts by deriving inferences.

- Electronic Document Repository: This layer complements the formal model by providing access to electronic documents in Akoma Ntoso [Palmirani & Vitali 2011]. Entities of the other layers, this are rules, concepts, etc., can be linked by using IRIs with legal text. This allows for supporting the decision making by the legal expert by providing statutes, commentaries and judgments as well. Moreover it fosters isomorphism of rules by linking them with their legal basis.

3.

Reasoning module and algorithm ^

4.1.

Theoretical background ^

There are several possibilities the legislator can adopt to reduce effort and cost of legal change management [Palmirani 2011]. Regardless of the methodology followed by the legislator a computable model of law has to deal with changes of sources of law somehow.

For the purposes of the current model we follow the «direct method» of [Palmirani 2011] and assume that each change of the sources of law (e.g. by an amendment) leads to a new consolidated version of a statute, containing untouched, modified and new provisions as well. The old version of the statute and its norms enter out of force before the day the new versions enter into force. This approach reduces the complexity of the temporal model.

4.2.1.

Temporal dimensions ^

- Existence: The period in which the norm is part of the legal system, starting with the day of publication (in an official journal), ended by a subsequent normative action.

- Force: When the norm is in force and thus can be applied by the judge in general. In Austria this period usually starts after the day of publication but can be deferred by vacation legis.

- Efficacy: The period in which facts must have occurred in order for the rule to be applicable is called the efficacy period.

- Applicability7: This is the period when a legal norm produces the consequences it establishes.

4.2.2.

Versioning legal rules ^

4.2.3.

Retroactive modifications ^

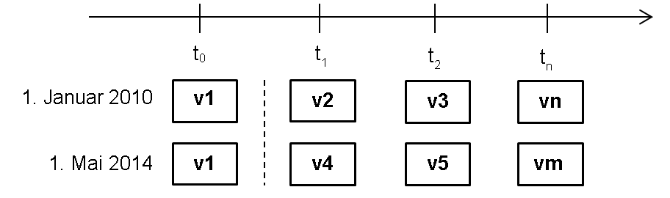

Figure 1 shows an example of an amendment published on 5 January 2014 which retroactively modifies v2 at time t1 and thus leads to a new versioning chain which contains the untouched v1 followed by the amended versions. Virtually the timeline gets split after v1 which is not affected by the modification, as indicated by the dashed line. There is no need to touch the existing chains. The retroactive change of v2 subsequently leads to an adaption of the following versions as well, thus we get the situation described above.

4.3.

Selecting applicable rules ^

5.

Modelling norms ^

5.1.

Presenting rule priorities ^

6.

Related work ^

7.

Conclusions and future work ^

At the moment rOWLer is designed as a single-agent system and the reasoning engine is optimized to deal with statutes with a rather mathematical content like tax law or «easy» cases13 in the terminology of Hart. The model of rOWLer is flexible enough to be extended in the future to handle «hard» cased as well, e.g. by providing the legal expert with different alternatives for decision making and integrating more sophisticated argumentation systems like Carneades.

8.

References ^

Athan, T. et al., 2013. OASIS LegalRuleML. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law – ICAIL «13. New York, USA: ACM Press, pp. 3–12.

Boer, A. & van Engers, T.M., 2011. A MetaLex and Metadata Primer: Concepts, Use, and Implementation. In G. Sartor et al., eds. Legislative XML for the Semantic Web. Law, Governance and Technology Series. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 131–149.

Ceci, M., 2013. Interpreting Judgements using Knowledge Representation Methods and Computational Models of Argument. University of Bologna.

Francesconi, E., 2011. Naming Legislative Resources. In G. Sartor et al., eds. Legislative XML for the Semantic Web. Law, Governance and Technology Series. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 49–74.

Gordon, T.F., 2011a. Analyzing open source license compatibility issues with Carneades. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law – ICAIL «11. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press, pp. 51–55.

Gordon, T.F., 2011b. Combining Rules and Ontologies with Carneades. In Proceedings of the 5th International RuleML2011@ BRF Challenge. Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA.

Hart, H.L.A., 1994. The Concept of Law 2. ed., Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Kelsen, H., 1979. Allgemeine Theorie der Normen, Wien: Manz.

Lam, H.-P. & Governatori, G., 2009. The Making of SPINdle. In G. Governatori, J. Hall, & A. Paschke, eds. Rule Interchange and Applications. New York: Springer, pp. 315–322.

Maher, M.J., 2004. Propositional defeasible logic has linear complexity. Theory and Practice of Logic Programming, 1(06), pp. 691–711.

Nute, D., 2003. Defeasible Logic. In O. Bartenstein et al., eds. Web Knowledge Management and Decision Support. Berlin: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 151–169.

Palmirani, M., 2011. Legislative Change Management with Akoma-Ntoso. In G. Sartor et al., eds. Legislative XML for the Semantic Web. Law, Governance and Technology Series. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 101–130.

Palmirani, M. & Brighi, R., 2006. Time Model for Managing the Dynamic of Normative System. In M. A. Wimmer et al., eds. Electronic Government. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 207–218.

Palmirani, M., Governatori, G. & Contissa, G., 2011. Modelling temporal legal rules. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law – ICAIL «11. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press, pp. 131–135.

Palmirani, M., Governatori, G. & Contissa, G., 2010. Temporal Dimensions in Rules Modelling. In R. G. F. Winkels, ed. Legal Knowledge and Information Systems, JURIX 2010: The Twenty-Third Annual Conference. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 159–162.

Palmirani, M. & Vitali, F., 2011. Akoma-Ntoso for Legal Documents. In G. Sartor et al., eds. Legislative XML for the Semantic Web. Law, Governance and Technology Series. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 75–100.

Saur, K.G., 2009. Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records: Final report., München: IFLA Study Group on the Functional Requirements for Bibliographic Records.

Scharf, J., 2014. rOWLer – A Hybrid Rule Engine for Legal Reasoning. In Proceedings of the Semantic Web for the Law and Second Jurix Doctoral Consortium Workshops. Kraków.

Walter, R., Mayer, H. & Kucsko-Stadlmayer, G., 2007. Grundriss des österreichischen Bundesverfassungsrechts 10. ed., Wien: Manzsche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung.

Johannes Scharf, PhD researcher, University of Vienna, Faculty of Law, Wiener Straße 73/1/6, 3002 Purkersdorf, AT, johannes.scharf@gmx.at

- 1 This is a slightly revised version of the paper presented at JURIX2014-DC at the Jagiellonian University, Kraków.

- 2 Johannes Scharf works as a software engineer at the federal computing center (Bundesrechenzentrum) in Vienna and as a PhD researcher at the University of Vienna.

- 3 These systems are mostly «production systems» formalizing law by using thousands of if-then-else statements.

- 4 This ensures more clean and maintainable code which is at the same time easier to understand and read.

- 5 For example due to the ruling of the Austrian Supreme Court of Justice regarding continuing obligations the time before an amendment has to be judged according to the old rules and afterwards according to the new ones.

- 6 It has to be noted, that the terms are not always used homogeneously in literature and are used with different meanings. The terms «efficacy» and «applicability» refer to «Bedingungsbereich» and «Rechtsfolgenbereich» respectively in German legal theory [Walter et al. 2007].

- 7 This refers strictly to temporal applicability, the derogation of norms, e.g. by EU law, is tackled in the second reasoning step of the proposed algorithm.

- 8 For the example we assume that the fiscal year coincides with the calendar year.

- 9 We use an object-oriented model.

- 10 The architecture of rOWLer is consistently based on interfaces which allows for using Java’s dynamic proxying facilities.

- 11 In this a sense superiority relation resembles a preference relation but in contrast to the latter it is an abstraction whose instances are built dynamically at runtime by the engine.

- 12 By referring to «Drools» we actually mean «Drools Expert» which is the rule engine of the Drools platform.

- 13 «Easy» cases can be largely decided «mechanically» by deducing the required result from the rule and the facts. «Hard» cases are ones for Hart in which the facts fall within the «penumbra» of the meaning of the words in the applicable rule. These cases require the judge to exercise discretion [Hart 1994].