1.

Introduction ^

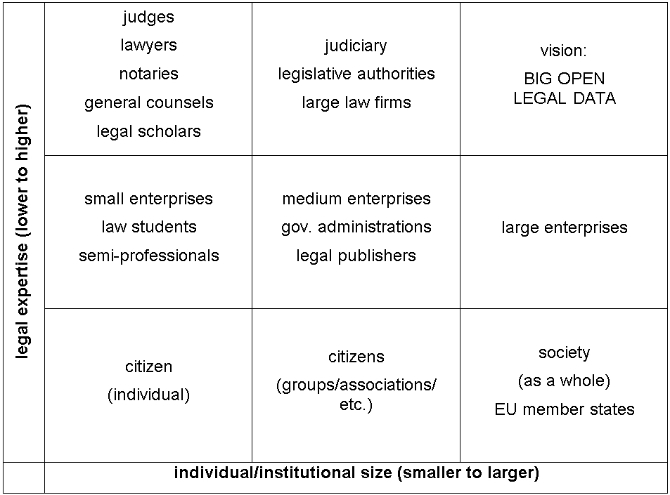

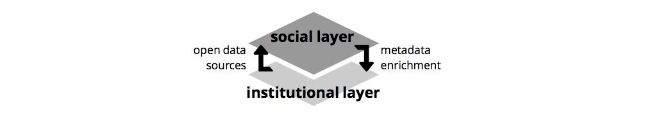

openlaws is an ambitious EU project1 that is built on open data, open innovation and open source software. openlaws will help you find legal information more easily, organize it the way you want and share it with others. The Internet platform is adding a «social layer» to the existing «institutional layer» of legal information systems. Together with the different stakeholders the project team will create a network between legislation, case law, legal literature and legal experts – both on a national and a European level, leading to better access to legal information. The openlaws core team will also create a «BOLD Vision 2020» about what Big Open Legal Data (BOLD) can do in the future and propose a roadmap to the European Commission (DG Justice). The initial concept was presented to the general public at the IRIS 2013 conference.2

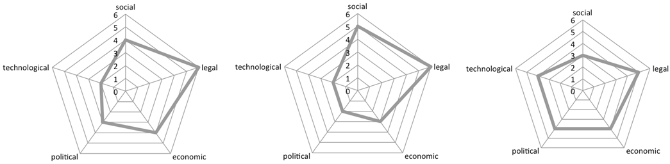

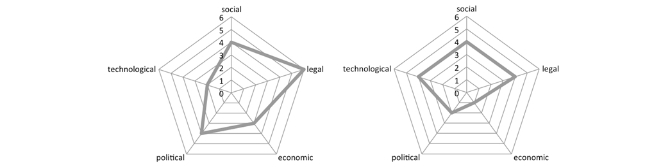

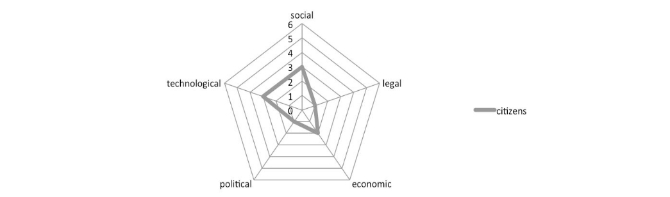

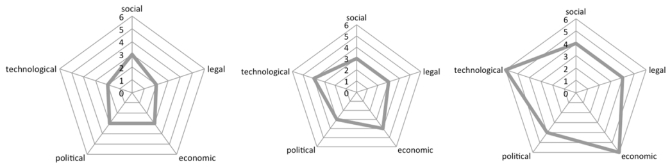

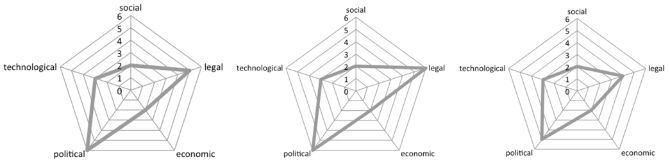

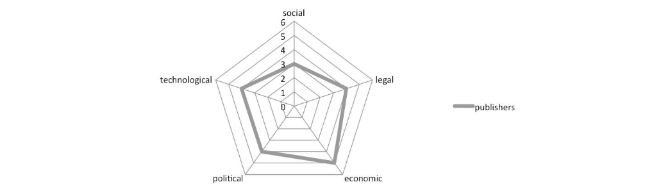

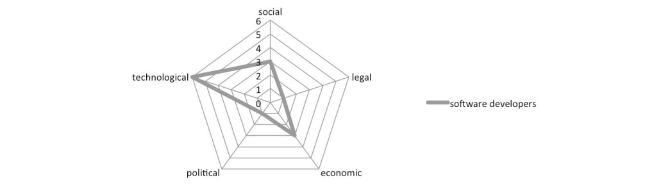

- Social factors include reputation of the stakeholder group, career opportunities, social security, the work environment, collaboration with peers and also demographic factors;

- Legal factors include mainly the legal expertise of this stakeholder group (please note the difference to a traditional SLEPT analysis, which refers to the legal framework that affects a specific business, such as consumer law, employment law, antitrust law, etc.);

- Economic factors include the financial setting for the stakeholder groups, including their income or revenue, their cost structure, etc.;

- Political factors cover the degree to which the government interferes in the stakeholder group and includes public policies with respect to the free movement of persons and goods as well as possible restrictions to (legal) data and the protection/openness of legal information;

- Technological factors include research and development possibilities, the degree of automation, the adoption rate of new technology etc.

2.

Legal Professionals ^

3.

Citizens ^

| EU Member State | Population | Language | Official legal databases |

| Austria | 8,375,164 | German | www.ris.bka.gv.at |

| United Kingdom | 63,022,532 | English | www.legislation.gov.uk |

| Netherlands | 16,655,799 | Dutch | www.overheid.nl |

| EU total | 504,961,522 | 24 languages | www.eur-lex.eu |

Table 1: population within the EU and the three initial openlaws member states5

While the openlaws.eu platform will not offer premium legal literature like publishers, it will be built on top of governmental databases (open data) and offer new and innovative features for citizens (tagging, bookmarks, linking, commenting, recommender systems7, etc.). It will also allow for creating links to the contents of participating publishers.

4.

Businesses ^

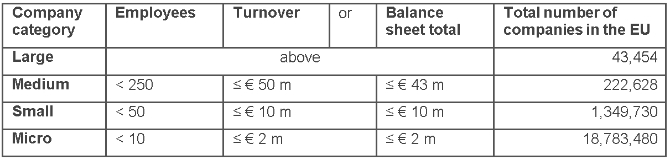

Table 2: number of companies within the EU8

5.

Governments ^

Laws have to be officially published to enter into force and effect. Today, governments use electronic publishing in addition to traditional publishing on paper. In a further step, government can make legislation and case law available as «open data» so that it can be used by the community.10 The public sector information (PSI) directive11 encourages the Member States to make as much information available for re-use as possible. New standards in the EU for references to legislation and case law foster the creation of a European-wide network.12

6.

Publishers ^

7.

Software Developers ^

8.

Conclusions and Outlook ^

Clemens Wass, Workstream Leader Dissemination and User Community Engagement, EU Project openlaws.eu, BY WASS GMBH, Felix-Ennmoserweg 13, 5061 Elsbethen, AT, clemens@bywass.com; http://www.bywass.com and http://www.openlaws.eu

- 1 openlaws.eu is cofunded by the European Union (DG Justice) und action grant JUST/2013/JCIV/AG grant no. 4562. The author thanks his project colleagues for their contribution. The full team is presented on the project website: www.openlaws.eu.

- 2 Wass, Clemens/Dini, Paolo/Heistracher, Thomas/Lampoltshammer, Thomas/Marcon, Giulio/Sageder, Christian/Tsiavos, Prodromos/Winkels, Radboud, OpenLaws.eu, in Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter (eds.), Abstraction and Application, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2013, Salzburg, Austria (2013).

- 3 See for example the «Master of Legal Studies (MLS)» program at the Executive Academy of the Vienna University of Economics and Business, https://www.executiveacademy.at/en/master-of-laws/master-of-legal-studies/, last accessed 8 January 2015.

- 4 Greenleaf, Graham/Mowbray, Andrew/Chung, Philip, The Meaning of «Free Access to Legal Information»: A Twenty Year Evolution (2012). Law via Internet Conference, 2012. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2158868 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2158868, last accessed 8 January 2015.

- 5 Eurostat, Population on 1 January by age and sex, last update: 13 August 2014, http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=demo_pjan&lang=en, last accessed 8 January 2015.

- 6 Please note that the legal database as such can be copyright protected, in particular under Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases and the respective national implementations.

- 7 Winkels, Radboud/Boer, Alexander/Vredebregt, Bart/Someren, Alexander, Towards a Legal Recommender System, Conference: 27th International Conference on Legal knowledge and information systems (JURIX 2014), at Krakow, Poland, Volume: Volume: 271. Frontiers in artificial intelligence and applications (2014); Opijnen, Marc van, A model for automated rating of case law, Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law (ICAIL 2013), pp. 140–149 (2013).

- 8 European Commission, Annual Report on European SMEs 2012/2013, http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/performance-review/index_en.htm, last accessed 8 January 2015.

- 9 These services are made available via the European e-Justice Portal, https://e-justice.europa.eu, last accessed 8 January 2015.

- 10 Wass, Clemens, Open Data as an Opportunity for Legal Information Services, in Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter (eds.), Transparency, Proceedings of the 17th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2014, Salzburg, Austria (2014).

- 11 Directive 2013/37/EU oft he European Parliament and of the Council of 26 June 2013 amending Directive 2003/98/EC on the re-use of public sector information.

- 12 Lampoltshammer, Thomas/Wass, Clemens, Neue Standards für Gesetze und Entscheidungen: ECLI und ELI, jusIT 04/14, pp. 155–157 (2014).