1.

Introduction: Pitfalls of Current Contracting – the Necessity of Change ^

Surveys conducted by the International Association for Contract and Commercial Management (IACCM) reveal that contract negotiators around the world spend most of their time on terms relating to risk management and negative incentives. Year after year, the list of Top Negotiated Terms is topped by limitation of liability and indemnities.2 At the same time, based on IACCM research,3 the following are the ten pitfalls of today’s contracting:

| 1: Lack of clear scope and goals | 6: Relationships lack flexibility, governance |

| 2: Commercial team involved late | 7: Contracts difficult to use or understand |

| 3: Failure to engage stakeholders | 8: Poor handover to implementation |

| 4: Protracted negotiations | 9: Limited use of contract technology |

| 5: Negotiations focus on risk allocation | 10: Weak post-award process governance |

These pitfalls present major risks for the companies and their bottom line.4 As articulated by Stewart Macaulay, a huge gap exists between the contract as written («the paper deal») and the true agreement («the real deal»).5 Adding to the challenges is the fact that according to IACCM research, more than 9 out of 10 managers admit that they find contracts difficult to read or understand.6 While our paper focuses on commercial contracting, this is not just a problem of managers working with contracts between businesses, of course. Similar challenges are faced in consumer contracting, public procurement, employment contracts, and contracts between individuals, both online and offline. And in all these contexts, the felt need to produce traditional legal language in contracts (i.e., lawyers drafting contracts for other lawyers)7 diverts drafters' attention away from the needed integration among those who construct the deal, draft the contract, and those who must carry it out.8

2.

Avoiding the Pitfalls – Facilitating Better Deal Design ^

In our previous work, we have looked into what lawyers can learn from designers17 and software engineers18. We have explored promising new approaches to better contract and deal design, such as transactional art and visualised negotiations19 as well as contract visualisation20. Prior research has revealed a number of ways to make contractual information more accessible and understandable, and several suggestions for avoiding current contracting pitfalls have been made.21 In this paper, we focus on visualisation. We argue that visualisation can help reduce the barriers to effective communications within an organisation, among and between business negotiators and lawyers, and between the contracting parties.

3.

Categorisation of Contract Visualisation: Adding Two New Categories ^

3.1.

Visualisation as Contracts ^

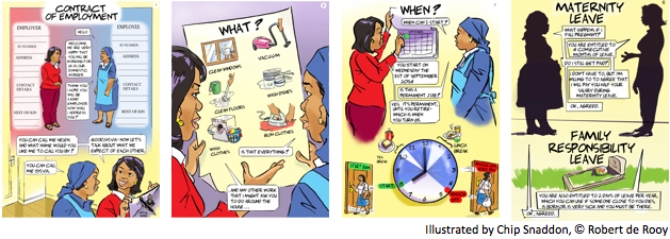

Visualisation as contracts posits that the visualisation of the agreement is the sole artifact of the agreement. There is no other or underlying text which overrides the visual representation. An early example of this new category is the «Comic Contract» introduced by de Rooy – representing the parties as characters engaged in a visual interaction or textual dialogue that simultaneously captures the agreement and its story. The comic may be enhanced with scenarios, diagrams or other visual devices.26 The use of text for names, dialogue, complementary narratives, numbers and symbols is not excluded, but only to support the visual format. This goes beyond the idea that the visualisation only serves to enhance the understanding of the contract and is not intended to replace its text.27

Apart from leveraging all the advantages of visualisation (such as understandability, memorising, and experience of the contract)28 and of stories29, it is a format that allows the contract to be presented contextually, i.e. a situational and temporal backdrop, and for the tone or «feeling» (friendly, courteous, formal) of the relationship to be represented. There are other advantages: for example, it allows the contract to be presented in the first and second person, enhancing the relevance, understanding and moral commitment of the parties to agreement. It also invites the benefits of the agreement being presented as a story, and as a sequence of questions and answers, which supports the readability and relevance of the «answer» in the context of the «question».

The concept of a comic as a contract is not without its challenges.31 Designing and drawing such contracts would require a trans-disciplinary effort between the clients, the lawyers, a scriptwriter and illustrator, with obvious cognitive effort and cost implications. There are also views that pictures may be overly ambiguous,32 that the understanding of pictures may be too subjective, or that the format may not meet the demands of more complex agreements.

3.2.

Visualisation for Contracts ^

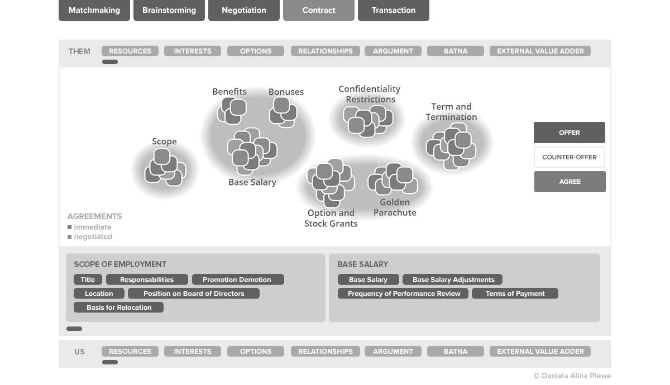

The actual negotiation is supported by the visual metaphor of a marketplace. All visual elements provide the option to be disambiguated through additional information in textual form. We consider flexibility and «associativity» important criteria for a contracting tool and aim to support brainstorming and creative methodologies as applied to other design processes.37

4.

Conclusion ^

5.

References ^

Argyres, Nicholas & Mayer, Kyle J., Contract design as a firm capability: An integration of learning and transaction cost perspectives, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 4, October 2007, p. 1060–1077. DOI: 10.5465/AMR.2007.26585739.

Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde, Bird, Robert C. & Haapio, Helena, Promoting Business Success Through Contract Visualization, The Journal of Law, Business & Ethics, Vol. 17, Winter 2011, p. 55–75.

Bresciani, Sabrina & Eppler, Martin J., The Pitfalls of Visual Representations: A Review and Classification of Common Errors Made While Designing and Interpreting Visualizations. SAGE Open, 14 October 2015. DOI: 10.1177/2158244015611451.

Conboy, Kevin, Diagramming Transactions: Some Modest Proposals and a Few Suggested Rules, Transactions: Tennessee Journal of Business Law, Vol. 16, 2014, p. 91–108.

Curtotti, Michael, Passera, Stefania & Haapio, Helena, Interdisciplinary Cooperation in Legal Design and Communication. In: Schweighofer, Erich, Kummer, Franz & Hötzendorfer, Walter (Eds.), Kooperation. Tagungsband des 18. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik Symposions IRIS 2015 / Co-operation. Proceedings of the 18th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2015. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG, Wien 2015, p. 455–462.

Haapio, Helena, Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift. Lexpert Ltd, Helsinki 2013(a).

Haapio, Helena, Visualising Contracts for Better Business. In: Svantesson, Dan Jerker B. & Greenstein, Stanley (Eds.), Internationalisation of Law in the Digital Information Society. Nordic Yearbook of Law and Informatics 2010–2012. Ex Tuto Publishing, Copenhagen 2013(b), p. 285–310.

Haapio, Helena, Making Contracts Work for Clients: towards Greater Clarity and Usability. In: Schweighofer, Erich, Kummer, Franz & Hötzendorfer, Walter (Eds.), Transformation of Legal Languages. Proceedings of the 15th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2012. Band 288. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft, Wien 2012, p. 389–396.

Haapio, Helena & Barton, Thomas D., Business-Friendly Contracting: How Simplification and Visualization Can Help Bring It to Practice. Forthcoming in Run Legal as a Business. Springer 2016.

Haapio, Helena & Passera, Stefania, Visual Law: What Lawyers Need to Learn From Information Designers, Cornell University Law School, Legal Information Institute, VoxPopuLII Blog 15 May 2013, http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2013/05/15/visual-law-what-lawyers-need-to-learn-from-information-designers/ (accessed on 5 January 2016).

IACCM, The Top Negotiated Terms: Negotiators Admit They Are On Wrong Agenda, Contracting Excellence Magazine, July 2009, https://www2.iaccm.com/resources/?id=8086 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

IACCM, Commercial Excellence: Ten Pitfalls To Avoid In Contracting. [Booklet] International Association for Contract and Commercial Management 2015(a), https://www2.iaccm.com/resources/?id=8451 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

IACCM, Top Negotiated Terms 2015: No News is Bad News, International Association for Contract and Commercial Management 2015(b), http://www2.iaccm.com/resources/?id=8930 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

Jüngst, H. E., Information Comics. Knowledge Transfer in a Popular Format. Leipziger Studien zur angewandten Linguistik und Translatologie, Vol. 7. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main; New York 2010.

Knackstedt, Ralf, Heddier, Marcel & Becker, Jörg, Conceptual Modeling in Law: an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda, Communications of the Association for Information Systems, Vol. 34, Article 36, January 2014, p. 711–736. http://aisel.aisnet.org/cais/vol34/iss1/36 (accessed on 5 January 2016).

Lannerö, Pär. Fighting the Biggest Lie on the Internet. Common terms beta proposal, 30 April 2013. Metamatrix, Stockholm. http://www.commonterms.net/commonterms_beta_proposal.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2016).

Macaulay, Stewart, The real and the paper deal: Empirical pictures of relationships, complexity and the urge for transparent simple rules, The Modern Law Review, Vol. 66, No. 1, 2003, p. 44–79. DOI:10.1111/1468-2230.6601003. http://www.law.wisc.edu/facstaff/macaulay/papers/real_paper.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2016).

Mahler, Tobias, A graphical user-interface for legal texts? In: Svantesson, Dan Jerker B. & Greenstein, Stanley (Eds.), Internationalisation of Law in the Digital Information Society. Nordic Yearbook of Law and Informatics 2010–2012. Ex Tuto Publishing, Copenhagen 2013, p. 311–327.

Malhotra, Deepak, Great Deal, Terrible Contract: The Case for Negotiator Involvement in the Contracting Phase. In: Goldman, Barry M. and Shapiro, Debra L. (Eds.), The Psychology of Negotiations in the 21st Century Workplace. New Challenges and New Solutions. Routledge, New York (NY) 2012, p. 363–398.

McCloud, Scott, Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art.William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers, New York 1994.

NEC, Guidance notes and flowcharts for the Professional Services Contract. NEC3. Thomas Telford, London 2005.

Passera, Stefania, Visual Negotiation maps: Focusing on customer needs and expectations during sales negotiations and contracting. In: User Experience and Usability in Complex Systems – UXUS 2010–2015, FIMECC UXUS Final Report 1/2015, FIMECC Publication Series No. 8, FIMECC, Tampere 2015, p. 174–177.

Passera, Stefania, Beyond the wall of text: how information design can make contracts user-friendly, in: Lecture Notes on Computer Science 9187 – Design, User Experience, and Usability: Users and Interactions (Part II) 2015.

Passera, Stefania & Haapio, Helena, The Quest for Clarity – How Visualization improves the Usability and User Experience of Contracts. In: Huang, Mai Lin & Huang, Weidong (Eds.), Innovative Approaches of Data Visualization and Visual Analytics, IGI Global, Hearshey (PA) 2013(a), p. 191–217.

Passera, Stefania & Haapio, Helena, Transforming Contracts from Legal Rules to User-centered Communication Tools: a Human-Information. Interaction Challenge, Communication Design Quarterly, Vol. 1, Issue 3, April 2013(b), p. 38–45.

Passera, Stefania, Haapio, Helena & Barton, Thomas D., Innovating Contract Practices: Merging Contract Design with Information Design. In: Chittenden, Jane (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2013 IACCM Academic Forum for Integrating Law and Contract Management: Proactive, Preventive and Strategic Approaches. Phoenix (AZ), USA, 8 October 2013. The International Association for Contract and Commercial Management, Ridgefield (CT) 2013, p. 29–51.

Passera, Stefania, Haapio, Helena & Curtotti, Michael, Making the Meaning of Contracts Visible – Automating Contract Visualization. In: Schweighofer, Erich, Kummer, Franz & Hötzendorfer, Walter (Eds.), Transparenz. Tagungsband des 17. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik Symposions IRIS 2014 / Transparency. Proceedings of the 17th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2014. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG, Wien 2014, p. 443–450.

Passera, Stefania, Pohjonen, Soile, Koskelainen, Katja & Anttila, Suvi, User-Friendly Contracting Tools – A Visual Guide to Facilitate Public Procurement Contracting, In: Chittenden, Jane (Ed.), Proceedings of the 2013 IACCM Academic Forum for Integrating Law and Contract Management: Proactive, Preventive and Strategic Approaches. Phoenix (AZ), USA, 8 October 2013. The International Association for Contract and Commercial Management, Ridgefield (CT) 2013, p. 74–94.

Plewe, Daniela Alina, Transactional Art – Interaction as Transaction. In: Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ‘08). ACM, New York 2008, p. 977–980 (part of a PhD thesis submitted at Sorbonne: Transactional Arts – Art as the Exchange of Values and the Conversion of Capital, 2010).

Plewe, Daniela, Towards Strategic Media. In: Wichert, Reiner, Van Laerhoven, Kristof & Gelissen, Jean (Eds.), Constructing Ambient Intelligence – AmI 2011 Workshops, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, November 16-18, 2011. Revised Selected Papers. Communications in Computer and Information Science Series, Vol. 277. Springer, Heidelberg 2012, p. 19–24.

Plewe, Daniela, A Visual Interface for Deal-Making. In: O’Grady, Michael J. et al (Eds.), Evolving Ambient Intelligence – AmI 2013 Workshops, Dublin, Ireland, December 3–5, 2013. Revised Selected Papers, Communications in Computer and Information Science Series, Vol. 413, Springer International Publishing, Switzerland 2013, p. 205–212. Part of a PhD thesis submitted at Sorbonne: Transactional Arts – Art as the Exchange of Values and the Conversion of Capital, 2010.

Salo, Marika, Haapio, Helena & Passera, Stefania, Putting Financial Regulation to Work. In: Proceedings of the 19th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2016.

Siedel, George J. & Haapio, Helena, Using proactive law for competitive advantage, American Business Law Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, 2010, p. 641–686.

Wong, Meng Weng, Haapio, Helena, Deckers, Sebastiaan & Dhir, Sidhi, Computational Contract Collaboration and Construction. In: Schweighofer, Erich, Kummer, Franz & Hötzendorfer, Walter (Eds.), Kooperation. Tagungsband des 18. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik Symposions IRIS 2015 / Co-operation. Proceedings of the 18th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2015. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG, Wien 2015, p. 505–512.

Zak, Paul J., How Stories Change the Brain. Greater Good. December 17, 2013, available at http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/how_stories_change_brain. (accessed on 7 January 2016).

Zak, Paul J., Why Your Brain Loves Good Storytelling. Harvard Business Review. October 28, 2014, available at https://hbr.org/2014/10/why-your-brain-loves-good-storytelling/ (accessed on 7 January 2016).

- 1 See IACCM 2009. The title says it all: «The Top Negotiated Terms: Negotiators Admit They Are On Wrong Agenda».

- 2 IACCM 2015a.

- 3 IACCM 2015b.

- 4 According to IACCM, on average, companies could be generating over 9 % improvement to their bottom line if they tackled the commercial issues that commonly undermine contract performance. This statistic, and others in IACCM 2015b, is drawn from IACCM research with its global, cross-industry membership, representing more than 12,000 organisations. See IACCM 2015b, 4.

- 5 Macaulay 2003.

- 6 IACCM 2015b, 6.

- 7 Berger-Walliser, Bird & Haapio 2011.

- 8 See, generally, Haapio & Barton 2016.

- 9 See, generally, Haapio & Barton 2016, Haapio 2013a, and Malhotra 2012.

- 10 Haapio & Barton 2016. According to Deepak Malhotra, in the process, many key decisions have been left to the lawyers, even in areas where business managers and subject matter experts could (and should) have made an important contribution; the latter, according to Malhotra, are in a much stronger position to negotiate better outcomes and relationships, not just safer ones (Malhotra 2012, 363–364. Emphasis added).

- 11 Malhotra 2012.

- 12 The approaches known as Proactive Law and Proactive Contracting emerged in the Nordic countries, initiated by a small team of Finnish researchers and practitioners (one of this paper’s authors being among them) in the late 1990s and early 2000s. In the context of contracting, the pioneers of the approach merged quality and risk management principles with Preventive Law, where the focus is on using the law and legal skills to prevent disputes and eliminate causes of problems, and added a promotive, positive dimension to the preventive dimension. Both dimensions can be instrumental in overcoming the contracting pitfalls. See, generally, Haapio & Barton 2016 and Siedel & Haapio 2010.

- 13 Haapio 2013a, p. 39. See also Haapio & Barton 2016 and Siedel & Haapio 2010.

- 14 Haapio & Barton 2016.

- 15 Argyres & Mayer 2007, p. 1065–1066.

- 16 Argyres & Mayer 2007, p. 1074.

- 17 Haapio & Passera 2013.

- 18 Passera, Haapio & Curtotti 2014, Curtotti, Passera & Haapio 2015 and Wong, Haapio, Deckers & Dhir 2015.

- 19 Plewe 2008 and 2013.

- 20 Passera, Haapio & Barton 2013, Berger-Walliser, Bird & Haapio 2011, Passera & Haapio 2013a and 2013b.

- 21 For ways to avoid the contracting pitfalls identified by IACCM, see also Haapio & Barton 2016.

- 22 Haapio 2013, p. 75.

- 23 For examples illustrating how visualisations can be used in contracts themselves, see, e.g., Haapio 2013a and 2013b, Passera & Haapio 2013a and 2013b, and Passera, Haapio & Curtotti 2014.

- 24 For a visual guide to public procurement contract terms, see Passera, Pohjonen, Koskelainen & Anttila 2013. The NEC contract flowcharts offer another example of images about contracts; they expressly state that the flowcharts are not contract documents, they are not part of the contract, and they should not be used for legal interpretation of the meaning of the contract. See, e.g., NEC 2005.

- 25 Mahler 2013. See also Conboy 2014.

- 26 For the potential of comics as a medium and for ways to define comics, see McCloud 1994. For information comics or educational comics, see also Jüngst 2010; for the use of comics in contract education, see Haapio 2013a, 77.

- 27 Cf. Berger-Walliser, Bird & Haapio 2011.

- 28 See, e.g., Passera 2015, Passera, Haapio & Barton 2013, Passera & Haapio 2013(a) and 2013(b), and Haapio 2012.

- 29 See, e.g., Zack 2013 and 2014.

- 30 During her PhD studies, Marietjie Botes has developed a comic to communicate complex genetic research information to the San community in South Africa to enable scientists to obtain adequate informed consent. Her research is expected to be published in 2016. Personal communication 6 November 2015.

- 31 These go beyond the recognised challenges of visualisation in general. For these, see Bresciani & Eppler 2015.

- 32 A point which has been extensively discussed in classical disciplines such as philosophy and aesthetics as well as in the context of knowledge representation for artificial intelligence and design heuristics.

- 33 Passera 2015.

- 34 Lannerö 2013, with references. For updates, see Related Work, http://commonterms.org/Related.aspx. For ways in which the EU has started to pay attention to how financial disclosures and pre-contractual information are presented so the addressees can access, understand, and actually use the information, see Salo, Haapio & Passera 2016.

- 35 Plewe 2013.

- 36 The representation of strategies is subject to additional modules.

- 37 Further research may take empirical findings with mind maps and notational tools catered to specific creative methodologies, such as design thinking, into account.

- 38 Plewe 2012.

- 39 See, e.g., Knackstedt, Heddier & Becker 2014, p. 712, proposing an interdisciplinary research agenda. The authors argue that conceptual modeling techniques used in the field of information systems (IS) design to support communication processes in the IS domain should be transferred to the legal domain in order to support communication between legal experts and legal laypersons.