1.

Research question ^

We distinguish two entities: an act and its legal meaning.1 We treat the legal meaning (further institutional meaning) as an abstract objective entity. In this paper, this entity is also viewed from an information systems perspective. Representing the institutional meaning in computers (legal machines) is a research question. We consider, for example, operations that strengthen or lessen the institutional meaning.

2.

The notions of content meaning and institutional meaning ^

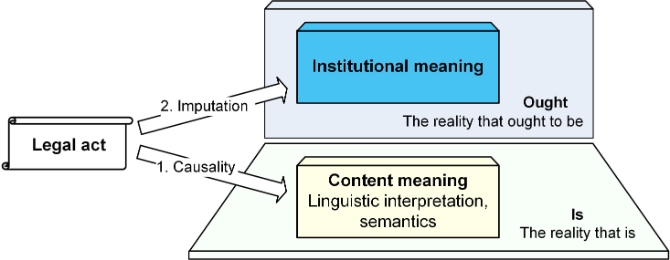

An act is a «happening occurring at a certain time and in a certain place» and the legal meaning of this act is «the meaning conferred upon the act by the law»2. Two kinds of «meanings» of a legal act can be distinguished (Figure 1):

- The content meaning. It appears in the Is realm (das Sein)3, «the reality that is»4. It is determined by causality. It is established by the content, information, semantics, and linguistic interpretation of a legal act. It is an objective entity. It is an intangible, abstract entity but linked with a fact, a material object such as a document or event in Is. The content meaning can be represented and processed by computers as data, for instance, the text of a document.

- The institutional meaning. It appears in the Ought realm (das Sollen)5, «the reality that ought to be»6. It is «the legal meaning of this act, that is, the meaning conferred upon the act by the law»7. It is determined by imputation8. It is also the meaning (der Sinn) and the objective legal meaning of the legal act (objektive rechtliche Bedeutung des Rechtsaktes). It is an objective entity. It is an intangible, abstract, nonfactual entity and not a material object. A computer, a digital machine, cannot understand it. A computer can process only representations (which appear in Is) of the institutional meaning.

Figure 1: The content meaning (Is) and the institutional meaning (Ought) of a legal act

Analogically, a legal fact such as an act of will (institutional fact) also has two kinds of meanings: the institutional meaning and the content meaning (Figure 2). We follow Neil MacCormick and Ota Weinberger’s terminology9 and their distinction of institutional facts and brute facts. Institutional facts like contracts, marriages, treaties, games, and so on are treated as objects that are not material.10 MacCormick and Weinberger focus on the legal meaning (Ought) of institutional facts.

Ought, the reality that ought to be, is characterized as a «spiritual, ideal, and moral reality»11. Hence, institutional facts have two links: 1) to Ought, and 2) to Is, the reality that is. Following the first link, an institutional fact is an abstract, spiritual, and ideal entity and is an abstract object, analogically to the way in which norms and legal institutions are also abstract objects. They really exist and «sometimes specific physical objects may have non-physical characteristics ascribed to them»12.

Content meaning comes from Is and corresponds to Pufendorf’s13 entia physica. Institutional meaning comes from Ought and corresponds to entia moralia. Content (further shorthand for content meaning) has to be legitimated through a process (which, for example, involves parliament) to become law.

Figure 2: The content meaning of an institutional fact and the institutional meaning

Different kinds of meanings. There are different kinds of meanings such as scientific meaning, cultural meaning, religious meaning, and so on. For instance, a speech act in science obtains scientific meaning. Thus for example, Copernicus wrote in Latin, whereas Galileo wrote in Italian. A consequence was that laymen could not understand Copernicus’s Latin but could understand Galileo’s Italian. A wedding ring is an example of cultural meaning which strengthens the legal meaning of marriage.

The world view of Falkenberg et al. supposes the presence of actors and actands and the «quality of causation»16. We note that their «causation» comprises both the causality and imputation. The imputation concept is present tacitly because a group of people agrees on shared conceptions. Therefore the notion of rule can also be defined.

3.

Strengthening or lessening of the meaning ^

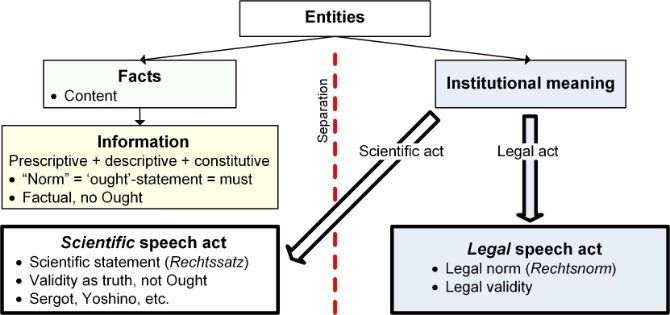

Content meaning. Institutional facts «are facts in virtue of being statable as-true statements»17. Kelsen’s term Rechtssatz was translated as «rule of law»18; however it can also be translated as legal statement (or sentence). These as-true statements embody the content meaning. They can be expressed linguistically and strengthened with the help of formal logic. Hence, formal logic can be applied. However, here the «ought» words are linguistic ones and not normative ones. Therefore the content meaning can comprise even contradictory statements.

Although the content information can be divided into prescriptive, descriptive, and constitutive statements, they are purely factual and linguistic and have no normative significance; cf., for instance, a child’s utterance. To add institutional meaning, the statements have to be accompanied by a legal act, for example, a legal speech act (Figure 3, right bold arrow). Scientific acts add no normative power; however, they can contribute to science and legal expert systems; cf. Hajime Yoshino’s Logical Jurisprudence.19

Figure 3: A legal act (right bold arrow) adds institutional meaning to statements. Scientific acts add no normative power but contribute to science and legal expert systems (left arrow)

Institutional meaning. Next to the content, we focus on the corresponding speech act, teleological statement, or legal act. Its intensity, that is, its quality, is important. It is, for instance, an officer’s draft, a ruling, a law with the same content, or even a constitutional law. Hence, the meaning (Kelsen’s Sinn) of a legal act resides in the existence of a draft, a ruling, a law, and so on. The institutional meaning of legal acts is concerned with their pragmatic effects. To sum up, the intensities of the existence can be distinct, although with the same content.

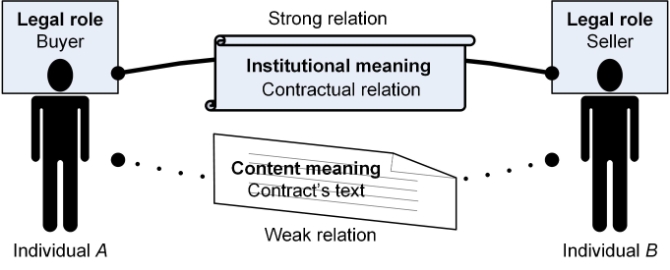

Semantics and pragmatics. The content meaning can also be called semantic meaning. The reason for this is that the linguistic interpretation is in the forefront here. Analogically, the institutional meaning can also be called pragmatic meaning. The content meaning has weak significance (schwache Bedeutung) compared with the strong significance (starke Bedeutung) of the institutional meaning. Here one can use the definition of semantics and pragmatics which is widely accepted in semiotics (also in Wikipedia)20:

- «Semantics: the relation between signs and the things to which they refer (i.e. their meaning)»21. «Semantics deals with the relation of signs to their designata and so to the objects they may or do denote»22.

- «Pragmatics: the relation between signs and the effects they have on the people who use them»23; «the relation of signs to their users»24.

Figure 4: The content meaning and the institutional meaning imply strong and weak relations

3.1.

Strengthening or lessening of the content meaning ^

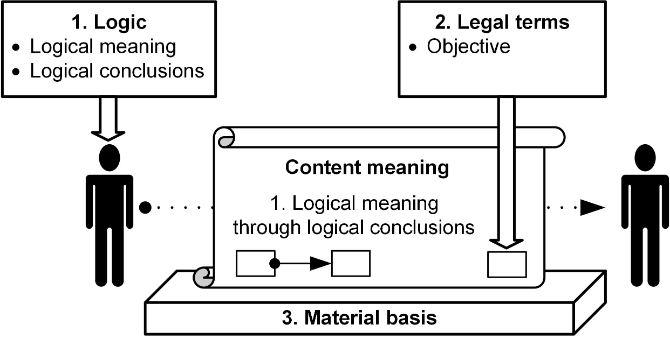

- Logic. Logical conclusions which follow from the premises can be stated clearly. Open texture can also be reduced. However, legal consequences (Ought) need not follow from a person’s statement (Is).

- Adding objective legal terms. Proper legal terms can be added, for instance, in contract use clauses such as performance, considerations, and so on.

- Material basis. The medium of a legal act can be stressed, for instance, the substrate, an (electronic) document, or the whole legal machine.

Figure 5: Strengthening the content meaning of a legal act

3.2.

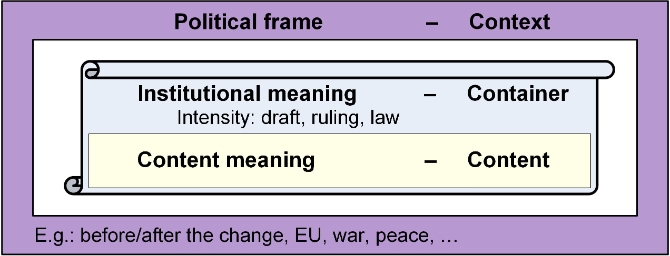

Political frame as context in semiotics ^

Figure 6: The political frame corresponds to the context in semiotics

4.

Two kinds of dualism: Is–Meaning (Sein–Sinn) and Is–Ought (Sein–Sollen) ^

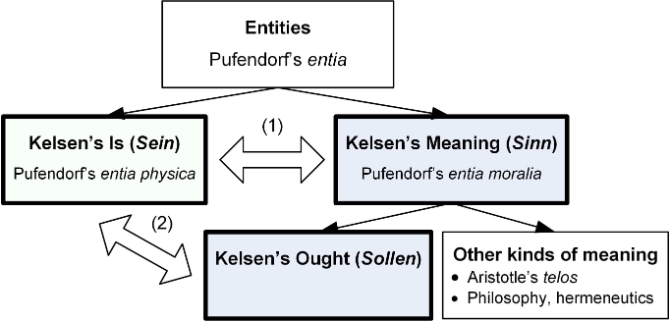

The dualism of Sein and Sinn was already considered by Samuel Pufendorf25, who divided entities into physical entities (entia physica) and moral entities (entia moralia)26; see Figure 7. Later Hans Kelsen spoke about Meaning (Sinn) and thus the Sein–Sinn dualism was revealed. Kelsen’s Meaning can be divided into distinct kinds: the legal meaning (Sollen) on which Kelsen focused, and other kinds of meanings. The latter exist because different sciences such as philosophy, hermeneutics, and so on explain the world differently and have different ontologies. To sum up, Kelsen concentrated on the dualism of Is (Sein) and Ought (Sollen).

Figure 7: Two kinds of dualisms: (1) Is–Meaning dualism considered by Pufendorf and Kelsen, and (2) Is–Ought dualism considered generally in law; cf. Kelsen, Pattaro, and so on.

The dualism of Is and Ought. Kelsen holds that Ought does not follow from Is.27 In formal logic, no indicative statement logically follows from a modal ought-statement. In other words, Obligatory p does not imply p. However, this does not mean that there is no relationship between Is and Ought. The direction of the conformance relationship points from Is to Ought.28

5.

Relating institutional meaning with representation ^

Figure 8: Modification in Ought is related with events in Is

Figure 9: The FRISCO semiotic tetrahedron, adapted from Falkenberg et al.29 and http://cs-exhibitions.uni-klu.ac.at/index.php?id=445.

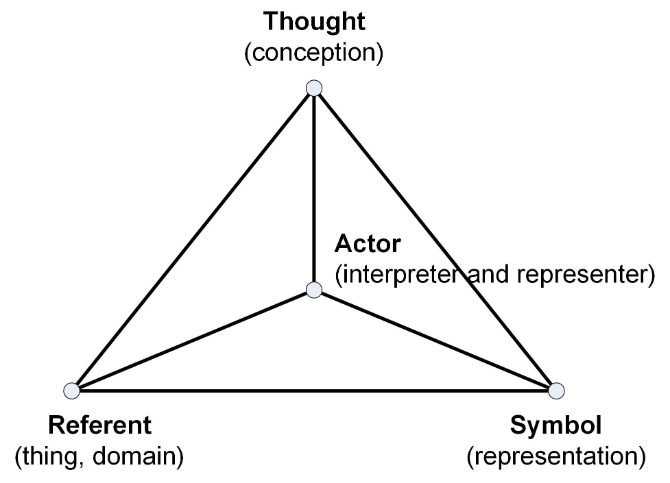

Our idea to link the institutional meaning of a legal act with its representations is inspired by the FRISCO tetrahedron (Figure 9). The FRISCO semiotic tetrahedron extends the three classical categories (the semiotic triangle) by an additional actor, an interpreter. He is a representer, a human actor involved in a representing action30. Meaning is defined as the relationship established by people in a language community between sign (symbol) standing for object (referent, thing)31.

Eight views are proposed in the eight-views/four-methods/four-syntheses approach by Schweighofer [2015]32. It serves the representation, analysis, and synthesis of legal materials as legal data science. This model describes the eight different representations of a legal system and four computer-supported methods of analysis, which lead to a synthesis, a consolidated and structured analysis of a legal domain, which may be either 1) a commentary, an electronic legal handbook, or 2) a dynamic electronic legal commentary DynELC, or 3) a representation for citizens, or 4) a case-based synthesis (Figure 10). The eight views (or representations of law) are: 1) text corpus, 2) metadata view, 3) citation network view, 4) user view, 5) logical view, 6) ontological view, 7) visualization view, and 8) argumentation view. The four methods are: 1) interpretation (search, reading, and understanding), 2) documentation (search and processing), 3) structural analysis (conceptual and logical), and 4) fact analysis.

Figure 10: Schweighofer’s eight-views/four-methods/four-syntheses model

6.

Related work ^

Representation is stressed by Mihai Nadin33, who writes about the semiotics of computation:

«The characteristic of semiotics, as Hausdorff understood and as Cassirer argued for is re-presentation. The fact that the means of representation can be called signs, or be defined as signs, is less relevant than the essential functions of semiotics. In close relation to representation is the function of interpretation through which meaning is conjured.»

Richard Fallon’s study34 of legal «meaning» can be related with our concept of content meaning. Fallon reveals many senses of the term «meaning» in legal argumentation:

«Examination of familiar terms of legal argument reveals an astonishing number of possible senses of that term – and, correspondingly, an equally large number of possible referents for ultimate claims concerning what legal provisions mean. These referents include a statutory or constitutional provision’s semantic or literal meaning, its contextual meaning as framed by shared presuppositions of speakers and listeners, its «real» conceptual meaning, and its intended, reasonable, and previously interpreted meanings»35.

Fallon advocates that «given the function of interpretive theories to guide or determine choices among otherwise plausible senses of legal meaning» such theories should do so on a case-by-case basis, not on a categorical basis.36

7.

Conclusions ^

Multiple representations of a legal act make sense. Each represents a different aspect of the legal meaning. The principle of content separation, which is common in software engineering, applies.37 Each stakeholder views a legal act differently.

The semiotic triangle by Ogden and Richards38 has to be extended to model sender-receiver communication. The reason is that the semiotic triangle deals with one person, a human agent. A semiotic square is a proper model.39 The FRISCO semiotic tetrahedron is a visualization of a more elaborate framework.

Vytautas Čyras, Associate Professor, Vilnius University, Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics.

Friedrich Lachmayer, Professor, University of Innsbruck.

- 1 Kelsen, Hans, Pure Theory of Law, 2nd ed., Knight, Max (transl.) (Reine Rechtslehre, 2. Auflage. Deuticke, Wien 1960), University of California Press, Berkeley 1967.

- 2 Kelsen 1967 (note 1).

- 3 Kelsen 1967 (note 1).

- 4 Pattaro, Enrico, The Law and the Right: A Reappraisal of the Reality That Ought to Be, Series A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence, volume 1, Springer, Dordrecht 2007, 3–5.

- 5 Kelsen, Hans, General Theory of Norms. Michael Hartney (transl.) (Allemeine Theorie der Normen, Manz Verlag, Wien, 1979) Clarendon Press, Oxford 1991. Kelsen writes: «The norm, as the specific meaning of an act directed toward the behavior of someone else, is to be carefully differentiated from the act of will whose meaning the norm is: the norm is an ought, but the act of will is an is» (Kelsen 1967, ch. 4.b, 5). Kelsen writes about the meaning of an act of will: «The Ought – the norm – is the meaning of a willing or act of will» (Kelsen 1991, ch. 1.III, 2). Kelsen treats Ought as a basic category and points out that a norm can be created not only by the act of will but also by custom (Kelsen 1991, ch. 1.IV, 2).

- 6 Pattaro 2017 (note 4), 3–5.

- 7 Kelsen 1967 (note 1).

- 8 Kelsen 1967 (note 1).

- 9 MacCormick, Neil/Weinberger, Ota, An Institutional Theory of Law: New Approaches to Legal Positivism, D. Reidel Publishing Co., Dordrecht, Boston 1986.

- 10 After introducing «brute facts», MacCormick/Weinberger 1986 (note 9) make the following observation about institutional facts: «However that may be, there are other entities which, albeit not material objects, we also commonly speak of as existing – things like contracts and marriages in the sphere of municipal law, treaties and international agencies (e.g. the Rome Treaties, the E.E.C. Commission) in the sphere of international law, games and competitions (e.g. the current World Cup Competition) in the sphere of social and sporting life» (MacCormick/Weinberger 1986 [note 9], 9–10).

- 11 Pattaro 2017 (note 4), 77.

- 12 MacCormick/Weinberger 1986 (note 9), 10.

- 13 Pufendorf, Samuel, De Jure Naturae et Gentium, 1672, English translation.

- 14 Falkenberg et al. write: «Constructivist: somebody who also believes that «reality» exists independently of any observer, but who is aware of the fact that we only have access to our own (mental) «conceptions»; for the constructivist, the relationship between reality and conception is principally subjective, and may be subject to negotiation between observers; any agreement – which we call «inter-subjective reality» – may have to be adapted from time to time». Falkenberg, Eckhard D./Hesse, Wolfgang/Lindgreen, Paul/Nilsson, Björn E./Oei, J.L. Han/Rolland, Colette/Stamper, Ronald K./Van Assche, Frans J.M./Verrijn-Stuart, Alexander A./Voss, Klaus, A Framework of Information System Concepts, The FRISCO Report (Web edition), IFIP, the Netherlands. http://www.mathematik.uni-marburg.de/~hesse/papers/fri-full.pdf (all websites last accessed 10 April 2018), 1998, 26, 29.

- 15 Falkenberg et al. 1998 (note 14), 32, write: «When a group [of people] agrees on the meaning of a particular representation, we will call its interpretation a shared conception. It is then assumed that there is a unique domain it refers to, i.e. an inter-subjective reality».

- 16 Falkenberg et al. 1998 (note 14), 30 write: «Assumption [f]: Some transitions may be conceived as being performed or brought about by some active things, called actors. Such a transition, called an action, is performed by that actor on passive things, called actands. […] We may further distinguish: (a) human and hence responsible actors (or groups, organisations, societies of persons), and (b) non-human and hence non-responsible and often inanimate and merely responsive devices (in particular machines and computers)».

- 17 MacCormick/Weinberger 1968 (note 9), 10, continue: «But what is stated is not true simply because of the condition of the material world and the causal relationships obtaining among its parts. On the contrary, it is true in virtue of an interpretation of what happens in the world, an interpretation of events in the light of human practices and normative rules».

- 18 Kelsen 1967 (note 1), 57–58.

- 19 Yoshino, Hajime, The Systematization of Law in Terms of the Validity. In: Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law, ICAIL «11, ACM, New York 2011, 121-125.

- 20 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semiotics.

- 21 Seifert, Uwe/Verschure, Paul F.M.J./Arbib, Michael A./Cohen, Annabel J./Fogassi, Leonardo/Fritz, Thomas/Kuperberg, Gina/Manzoli, Jônatas/Rickard, Nikki, Semantics of Internal and External Worlds. In: Arbib, Michael A. (Ed.), Language, Music, and the Brain: A Mysterious Relationship, Strüngmann Forum Reports volume 10, 203–232, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/stoutlab/files/2013/07/Language-Music-and-the-Brain.pdf, 2013, 213.

- 22 Morris, Charles W., Foundations of the Theory of Signs. In: Neurath, Otto/Carnap, Rudolf/Morris, Charles W. (Eds.), International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, volume 1, no. 2, 1–59, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago. https://www.scribd.com/doc/51866596/Morris-1938-Foundations-of-Theory-of-Signs, 1938, 21.

- 23 Seifert et al. 2013 (note 21), 213.

- 24 Morris 1938 (note 22), 33.

- 25 Puffendorf 1672 (note 13).

- 26 http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pufendorf-moral/.

- 27 Kelsen writes: «Nobody can assert that from the statement that something is, follows a statement that something ought to be, or vice versa.» (Kelsen 1967 [note 1], ch. 4.b, 6).

- 28 Kelsen writes: «This dualism of is and ought does not mean, however, that there is no relationship between is and ought. One says: an is conforms to an ought, which means that something is as it ought to be; and one says: an ought is «directed» toward an is―in other words: something ought to be.» (Kelsen 1967 [note 1], ch. 4.b, 6).

- 29 Falkenberg et al. 1998 (note 14), 51.

- 30 Falkenberg at al. 1998 (note 14) , 48.

- 31 Falkenberg at al. 1998 (note 14), 195.

- 32 Schweighofer, Erich, From Information Retrieval and Artificial Intelligence to Legal Data Science. In: Schweighofer, Erich/Galindo, Fernando/Cerbena, Cesar (Eds.), Proceedings of MWAIL 2015, ICAIL Multilingual Workshop on AI & Law Research, held within the 15th Int’l Conf. on Artificial Intelligence & Law (ICAIL 2015), OCG, Vienna 2015, p. 13-23.

- 33 Nadin, Mihai, Information and Semiotic Process: The Semiotics of Computation. Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 2011, volume 18, no. 1–2, 153–175.

- 34 Fallon, Richard H., The Meaning of Legal «Meaning» and its Implications for Theories of Legal Interpretation, University of Chicago Law Review volume 82, issue 3, http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol82/iss3/3, 2015, 1235–1308.

- 35 Fallon 2015 (note 34), 1235.

- 36 Fallon 2015 (note 34), 1235.

- 37 Goedicke, Michael, Paradigms of Modular System Development. In: Mitchell, Richard J. (Ed.), Managing Complexity in Software Engineering, IEE Computing Series 17, Peter Peregrinus, London 1990, 1-20.

- 38 Ogden, Charles Kay/Richards, Ivor Armstrong, The Meaning of Meaning. Harcourt, Brace & World, New York 1923, 11.

- 39 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Triangle_of_reference.