1.

Introduction ^

2.

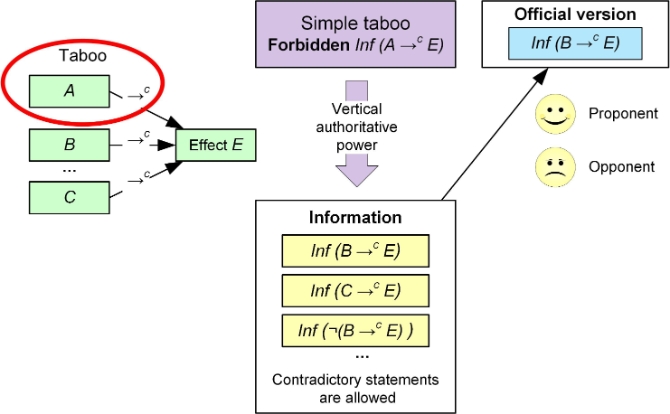

Taboo as a Prohibition to Speak ^

T X = def F Inf (X)

where T is treated as a modal operator that is syntactically analogical to the deontic operators O, P and F. Formalisation of normativity implies a norm as an entity. A taboo on X means a norm that prohibits informing about X:

Taboo(X) = def N(¬Inf (X))

(1)

In our formalisation, all the entities, including actions, facts and norms, exist as truth (true or false) in the realm of science, i.e. in a model such as a database. Norms N(•) correspond to the Ought realm or its representation in the model, while Inf corresponds to the Is realm.

N(A) → O(A) – From a commandment, an obligatory duty arises

N(¬A) → O(¬A) – From a prohibition, a prohibitive duty arises.

Meta-taboo. Next we strengthen the above definition with a double prohibition called a meta-taboo. A meta-taboo is a prohibition on informing that there is norm that prohibits speaking about X:

Meta-taboo (X) = def N(¬Inf (N(¬Inf(X))))

(2)

3.

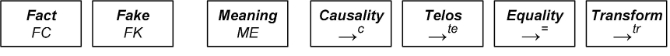

Three Levels of Norms on Prohibition ^

- N1(FC) means a commandment to establish a fact FC. For instance, N(door_closed), represents a commandment to close the door. Closing the door is a compliant action. This type of norm refers to Fact; see Figure 3.

- N1(¬FC) means a prohibition of a fact FC. For instance, N(¬door_closed), means a prohibition on closing the door. Opening the door is a compliant action. This type of norm also refers to Fact.

- N1(FK) means a commandment to establish a fake FK. As an example, imagine a community of liars. This type of norm refers to Fake.

- N1(¬FK) means a prohibition of a fake. This is a normal case. In general, fake facts are prohibited. For instance, news with false content is prohibited; the use of counterfeit money is also prohibited. This type of norm refers to Fake.

- ¬N1(FC) means an absence of commandment to establish a fact FC. We hold that an absence of a norm about a fact weakly implies a norm about a fake. As an example, we suppose a world with one door, and suppose that the door is closed. Hence, the proposition «‹The door is closed› is a fact» is true. Suppose that ¬N1(door_closed) holds in this world. The latter means the absence of any commandment to close the door. Next, suppose a fake news report of «The door is opened». However, nobody is obliged to react to this fake, because of the absence of any commandment to close the door. In this sense, the fake is compliant in this world. Therefore we hold that the type ¬N1(FC) refers to Fake.

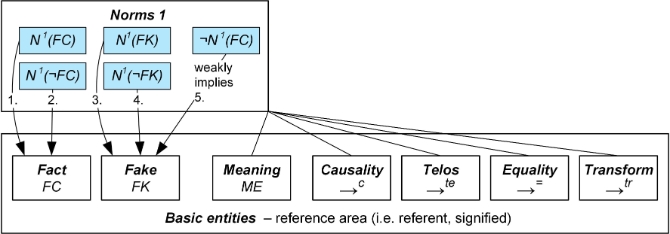

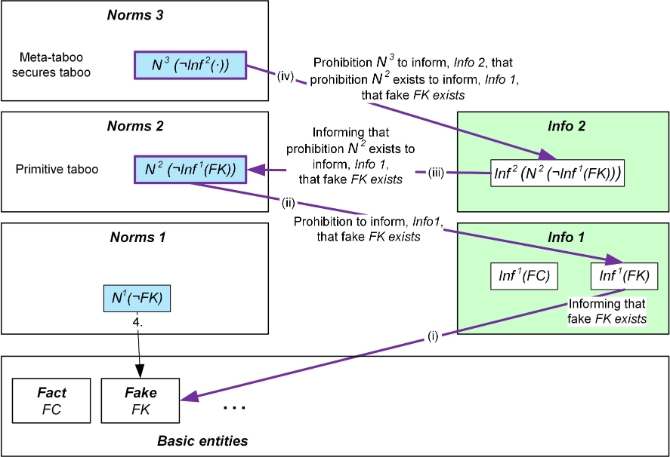

Second-level norms, Norms 2, formalise primitive taboos; see Figure 4. Here, norms are of the type

N 2(¬Inf 1(FK))

(3)

The third-level norms, Norms 3, formalise meta-taboos. Here the norms are of type N 3(¬Inf 2(•)). This means a prohibition N 3 on informing Inf 2 about anything; see link (iv) in Figure 5. Specifically, Norms 3 comprise a prohibition N 3 to inform, Info 2, that a prohibition N 2 exists to inform, Info 1, that a fake FK exists. Thus a meta-taboo secures a primitive taboo; see the top-down path (iv)–(iii)–(ii)–(i) in Figure 5.

N 2(¬Inf 1(«The emperor is naked» is a fact))

N 2(¬Inf 1(«The emperor is wearing new clothes» is a fake))

4.

Taboo on a Combination of Three Elements of a Relation ^

In mathematics, a binary relation R between two sets S1 and S2 is defined as a subset of a Cartesian product R⊂ S1×S2. For any x∈S1 and y∈S2 we write xRy to abbreviate (x,y)∈R. Elements of the set R are pairs (x,y). A binary relation can be represented with a two-column table.

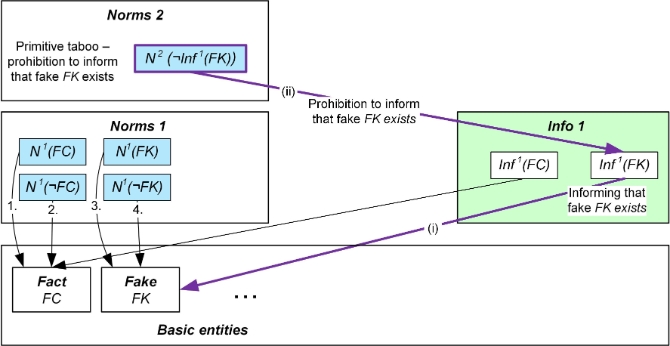

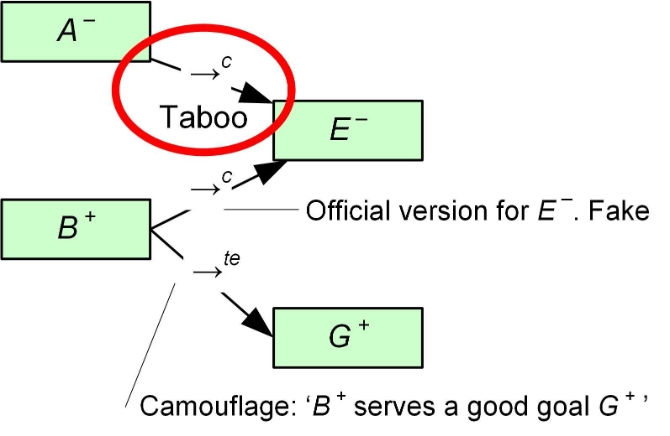

Figure 6: A taboo on a causal relationship A – →c E – is camouflaged in three steps, with a teleological relation →te between B + and a certain goal G +, which is evaluated positively: 1) in fact, both A – and E – are evaluated negatively; 2) therefore, the official version is announced that a certain cause B +, which is evaluated positively, causes E –; 3) a camouflage is that B + serves a good goal G +, which outweighs E –

5.

Related Work ^

6.

Conclusions ^

7.

References ^

Attridge, John, «A Taboo on the Mention of Taboo»: Taciturnity and Englishness in Parade’s End and André Maurois» Les Silences Du Colonel Bramble. International Ford Madox Ford Studies 2014, vol. 13, 23–35.

Broyde, Michael J., Informing on others for violating American law: a Jewish law view. Journal of Halacha and Contemporary Society 2002. http://www.jlaw.com/Articles/mesiralaw2.html.

Centola, Damon/Willer, Robb/Macy, Michael, The emperor’s dilemma: a computational model of self-enforcing norms. American Journal of Sociology 2014, 110(4), 1009–1040. http://ndg.asc.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Centola-et-al-2005-AJS.pdf, 2005.

Duschinsky, Robbie, Taboo, overview. In: Teo, Thomas (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Critical Psychology, pp. 1921–1923. Springer, New York 2014.

Freud, Sigmund, Totem and Taboo, Routledge, 2001 [1919] (Totem und Tabu, 1913).

Hansen, Jens Ulrik, A logic-based approach to pluralistic ignorance. In: Academia.edu 2011. http://www.academia.edu/1894486/A_Logic-Based_Approach_to_Pluralistic_Ignorance.

Lachmayer, Friedrich, Grundzüge einer Normentheorie: Zur Struktur der Normen dargestellt am Beispiel des Rechtes. Duncker und Humblot, Berlin 1977.

Prentice, Deborah A./Miller, Dale T., Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1993, 64(2), 243–256.

Steiner, Franz, Taboo. Cohen & West, London 1956.

- 1 The Oxford Dictionary, https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/taboo (all websites last accessed on 1 January 2018).

- 2 See Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taboo and Encyclopædia Britannica Online, «Taboo». Common taboos involve restrictions on or ritual regulations for killing and hunting; sex and sexual relationships; reproduction; the dead and their graves; and food and dining (primarily cannibalism).

- 3 Danish author Hans Christian Andersen wrote about two weavers who promise an emperor a new suit of clothes, which they say is invisible to those who are unfit for their positions, stupid, or incompetent. When the Emperor parades before his subjects in his new clothes, no one dares to say that they don’t see any suit of clothes on him for fear that they will be seen as «unfit for their positions, stupid, or incompetent». Finally, a child cries out, «But he isn’t wearing anything at all!» The story is about a situation where «no one believes, but everyone believes that everyone else believes. Or alternatively, everyone is ignorant as to whether or not the Emperor has clothes, but believes that everyone else is not ignorant.» [Hansen 2011]; see Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Emperor’s_New_Clothes.

- 4 Duschinsky begins with the following definition: «‹Taboo› is a Polynesian term, which has come to refer in Western academic and public discourses to topics, spaces, or practices that are consecrated as prohibited or to the process itself of marking them off» [Duschinsky 2014].

- 5 Steiner defines: «Taboo is concerned (1) with all the social mechanisms of obedience which have ritual significance; (2) with specific and restrictive behaviour in dangerous situations. One might say that taboo deals with the sociology of danger itself, for it is also concerned (3) with the protection of individuals who are in danger, and (4) with the protection of the society from those endangered – and therefore dangerous – persons… [T]aboo is an element of all those situations in which attitudes to values are expressed in terms of danger behaviour» [Steiner 1956, 20–21].

- 6 Centola et al. write: «It is easy to explain why people comply with unpopular norms – they fear social sanctions. And it is easy to explain why people pressure others to behave the way they want them to behave. But why pressure others to do the opposite? Why would people publicly enforce a norm that they secretly wish would go away?» [Centola et al. 2005].

- 7 John Attridge [2014] writes about the depiction of Englishness in novels. He notes that it was Archibald Lyall who called the «taboo on the mention of taboo›, in his 1930 book «It Isn’t Done, or, the Future of Taboo Among the British Islanders».

- 8 «[T]he classroom example in which, after having presented the students with difficult material, the teacher asks them whether they have any questions. Even though most students do not understand the material they may not ask any questions. All the students interpret the lack of questions from the other students as a sign that they understood the material, and to avoid being publicly displayed as the stupid one, they dare not ask questions themselves. In this case the students are ignorant with respect to some facts, but believe that the rest of the students are not ignorant about the facts.» [Hansen 2011]

- 9 «It is not difficult to find other familiar examples of compliance with, and enforcement of, privately unpopular norms: 1. the exposure of the ‹politically incorrect› by the righteously indignant who thereby affirm their own moral integrity; 2. gossiping about a social faux pas by snobs anxious to affirm their own cultural sophistication; 3. public adoration of a bully by fearful schoolboys who do not want to become the next victim; 4. ‹luxury fever› (Frank 2000) among status seekers who purchase $50 cigars, $17,000 wristwatches, and $3 million bras, in an arms race of conspicuous consumption and one-upmanship that leaves the contestants no happier but perhaps a bit less affluent.» [Centola et al. 2005]