1.

Introduction ^

Due to the growing popularity of social networks, the question of what should happen to a user’s account after his death is becoming increasingly relevant. Citizens are so actively using Internet services, that it has become part of their daily lives. In 2007 Facebook introduced memorialized accounts as a way to remember those who have passed away. In 2015, Facebook expanded its functionality by creating a «legacy contract», which allows the user to indicate to whom he wants to entrust the management of his account after death (Brubaker & Callison-Burch, 2016). Google Docs is owned by Google LLC, and, consequently, can be controlled with help of Google Inactive Account Manager. This service tracks last sign-ups, user’s recent activity, usage of Gmail and Android check-ins to estimate whether account is still being used (Google, 2019). On July 12, 2018, the Federal Court of Justice in Germany allowed the inheritance of social networks’ accounts. The judges explained their judgment by the fact, that if the heir enters into all legal positions of the deceased, he or she also enters into contractual relations. Accordingly, here is no reason to treat digital content differently (Janisch, 2018).

Until recently, the concept of digital rights and digital inheritance was completely absent in Russia. This is despite the fact, that the popularity of social networks and online services in general is growing rapidly. Social networks are extremely powerful in the sense of data collection. According to the Russian Public Opinion Research Center, 45% of Russians use at least one social network every day and 62% use at least one social network at least once a week. There are only 10% of Russians that do not have any accounts in any social network (BЦИОМ, 2018). Brand Analytics (2018) made a report about their study in 2018, where they investigated 8 popular social networks in Russia: it turned out that Russians write about 1.8 billion posts per month. This is a significant amount of content, and the question whether social networks’ accounts should be inherited is acute. However, Yandex, Russian largest search engine machine and service provider, refused to transfer ownership of the account or any information to the relatives of the deceased, referring to the Article 23 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation, which states that everyone has the right to privacy (Stepanov, 2014).

In March 2019 Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the law on digital rights, which came in force on October 1, 2019 (Фе∂еральныŭ ɜaкон om 18.03.2019 N 34-ФЗ, 2019). The document introduced the concept of digital rights into objects of civil rights. Through an analysis of 33 social networks and online services, a survey of 173 Internet users and expert interviews, we demonstrate that this innovation alone does not represent a sufficient approach to adequately regulate the digital heritage. After examining relevant legal norms in Russia, the current functionalities of exemplary social networks and online services for regulating the digital heritage, that are most popular in Russia, and the perspective of Internet users, we propose models that can foster the development of digital heritage in Russia.

We address the following research questions:

- How can Internet users in Russia currently manage their digital heritage?

- What expectations do Internet users in Russia have regarding the regulation of their digital heritage?

- Which solutions seem suitable for making Russia’s digital heritage more user-friendly and responsive?

This paper is structured as follows: section 2 describes the methodology that we used to conduct our study. In section 3, we describe current legal framework in Russia with help of legal documents together with legal experts. This chapter allows to see whether it is already possible to bequeath or to inherit an online account and which barriers of digital inheritance arise in the Russian legislation. In section 4, we investigate the most popular service providers in Russia in order to find out their attitude towards digital inheritance. Section 5 describes the population survey phase as well as data evaluation and interpretation. Section 6 contains the solution model proposal. Section 7 contains conclusion, discussion as well as propositions for future work.

2.

Methodology ^

To answer the first two research questions, three main steps were defined: an analysis of online services, carrying out of expert interviews, and population survey implementation.

The first step of analyzing the current possibilities of digital inheritance was the selection and classification of relevant services. We selected the most popular instant messengers according to an article from the Russian business daily «Vedomosti» (КодАчигов, 2018), and social networks and other online resources using Yandex.Radar analytical service, which tracks the 10,000 most popular Internet projects in Russia and sorts them by type, subject and user data. Of interest are those services, for which one need to register, and where one can also upload own content, write comments and leave other digital footprints. Thus, 33 services were selected: Airbnb, Apple Music, BabyBlog, BlaBlaCar, Cloud @Mail.Ru, Drive2, eBay, Facebook, Fishki.net, Google Docs, Google Drive, Instagram, Ivi, KinoPoisk, LitRes, LiveJournal, Netflix, Odnoklassniki, Office 365, Pinterest, Rambler Mail, Sberbank Online, Skype, Snob.ru, Spasibo from Sberbank, Steam, Tinder, Twitter, Viber, VKontakte, WhatsApp, Yandex.Money, and YouTube. As a first step, Terms of Use, User Agreements and FAQ pages of each selected service were investigated in order to find relevant information. In case there was no such information found, support center was contacted.

While literature search provides a broad overview, expert interviews were needed for a deeper understanding of today’s situation. For this purpose, interviews were conducted with both experts from the field of civil law of the Russian Federation and exemplary online service providers.

The population survey took place in two forms – a personal interview and an online survey. The purpose of personal interviews was to uncover the topic in a full conversation with respondents and come across new ideas regarding digital inheritance in Russia. The data collection took place from the August 7 to September 11, 2019. Personal interviews were conducted in Ufa, one of the largest cities in Russia. The purpose of the online survey was to reach out as many different parts of the country as possible in order to present a wider picture of Russia. When developing the survey poll, the Nellius, Zepic, and Krcmar (2019) questionnaire was taken as the base and adapted for a Russian user. This was used to elaborate user expectations of a digital heritage in Germany.

3.

Current Legal Framework in Russia ^

On the March 18, 2019, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed Federal Law N34-FZ, the purpose of which is to create the basis for regulating relations in the digital economy of Russia (Фе∂ерaльныŭ ɜaкон om 18.03.2019 N 34-ФЗ, 2019). The main value of the new law is that the sixth chapter of the first part of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation is supplemented by a new article – Article 141.1 on digital rights. According to paragraph 1 of this article, digital rights are recognized as obligations and other rights, the content and conditions for the implementation of which are determined in accordance with the rules of an information system that meets the criteria established by law (ГК РФ Cm. 141.1. ЦuФровые nрaвa, 2019). According to paragraph 2 of the same Article 141.1, the owner of digital rights is a person who, in accordance with the rules of the information system, has the ability to dispose of this right. From these two points it follows that, theoretically, an account on an online service falls under the concept of digital law, since the user accepts the terms of the User Agreement of the service provider, thereby acquiring a range of rights and obligations related to the use of the platform where the user is registered.

Despite the fact that in Russia there is no prohibition on the inheritance of online accounts, the law also does not fix this right. From October 1, 2019, digital rights are secured in Art. 128 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation as objects of civil rights, which allows counting on the possibility of transferring such rights by inheritance (ГК РФ Cm. 128. Объекты гражданских прав, 2019). However, a number of user problems, that arise when trying to bequeath or inherit an account, remain unresolved:

- The inheritability depends on the terms of use of each service providers, which most users simply jump over. Many services provide a non-transferrable license, which means that the only person who has right to have access to account on the service and to content published on the service is the user himself who has agreed to terms and conditions established by the administration of the service.

- A service provider may not be registered in the Russian Federation. One of the legal experts has noted during interview that even if the heirs seek access to the account through the court and a positive decision is made, the service provider may refuse to execute the court decision if it is not registered in the Russian Federation.

- Another obstacle to inheritance of online accounts is Article 23 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation on the right to protect personal life and keep confidentiality correspondence (Конституция Российской Федерации.. Cm. 23, 2019). In this case, Article 23 covers not only the rights of the deceased. Even if the testator himself expresses a desire to transfer access to correspondence to the heir, giving the heir access to the account automatically provides the heir with the access to the privacy and legally protected secrets of third parties with which the testator entered into personal, family or professional relations during his or her life (Шатилина, 2015, p. 78).

- From the previous paragraph follows another problem – the question of the safety of personal data and data protection, especially for e-mail services. The widespread throughout the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is not applicable in Russia. In Russian Federation, its own law is in force – the law on personal data N152-FZ dated 27 July 2006. The purpose of this law is to ensure the protection of the rights and freedoms of man and citizen in the processing of his personal data. In this law, heirs are mentioned only once – «in the event of the death of the subject of personal data, consent to the processing of his personal data, if such consent was not given by the subject of personal data during his lifetime, is given by the heirs of the subject of personal data» (Фе∂ерaльныŭ ɜaкон om 27.07.2006 N 152-ФЗ (ре∂. om 31.12.2017) «О nерсонaльныx ∂aнныx,» 2006). Furthermore, according to this law, operators and other persons who have gained access to personal data are required not to disclose to third parties and not to distribute personal data without the consent of the subject of personal data, unless otherwise provided by federal law. Russian lawyers disagree whether it is worth considering an e-mailbox as personal data, since there is no exact list anywhere, what can be considered as such personal data.

- According to Article 1112 of the Civil Code of the Russian Federation, the inheritance does not include rights and obligations inextricably linked with the identity of the testator (ГК РФ Сm. 1112. Haсле∂смво, 2019). User accounts, in fact, fall precisely into this category – personal profiles are inextricably linked with the user’s identity.

4.

Current opportunities for handling the account of deceased in the Russian Federation ^

Only 5 of the 33 services provide precaution functions. Support centers of 10 more services have claimed that the user is allowed to leave his or her login information in the testament or to share it with the heir, giving a full access to the account. However, 6 of these services actually forbid such actions in their Terms of Use or User Agreements; hence, only 4 of these 10 accounts can actually be counted. Thus, only on 9 of 33 platforms, a user is allowed in some way to settle his or her digital legacy. Out of 33 investigated services only 6 actually take care of the accounts of the deceased users; additionally, 6 more services track user’s activity and delete inactive accounts after a defined period of time. None of the services provides login credentials to third parties and 27 services confirmed that they delete account of the deceased after representatives provide proofs of death.

5.

Population survey ^

During the 6 weeks of the survey, the link to the survey was clicked 478 times, 247 people started the survey and 165 of them successfully completed it, reaching the final page. A personal interview was successfully conducted with 20 people, 4 more refused to take the survey, explaining this by unwillingness to think about death. It is most likely that people who have interrupted the online survey did that for the same reason. One of the respondents who has finished the online survey left the comment that it was an uncomfortable experience since «the questions were extremely unpleasant». Such a massive reluctance to think about death may be due to omens and superstitions, which are a great cultural component of Russian traditions.

Since the target group of the study is Russian residents who are active on the Internet, 9 records that were completed by non-residents of the Russian Federation and 2 records where respondents have claimed to have 0 accounts had to be excluded from 165 online interviews. Furthermore, as recommended by Leiner (2013), in order to remove meaningless data caused by rushing, records with relative speed index above 2.0 were excluded. Thus, one more record was deleted. Hence, 153 valid records from an online survey and 20 from a personal interview with a total of 173 cases were evaluated.

5.1.

Results of the survey ^

It is striking, that 82 out of 247 people (33.20%) have dropped the online survey and 4 out of 24 (16.67%) refused to give a personal interview. As already mentioned before, the potential reason for the refusal might lie in the reluctance to think about death. Two respondents expressed the opinion that digital inheritance in Russia will not be relevant soon («It will be relevant in a dozen years»; «It seems to me that in Russia they will think about it when I will be gone, and no one will be able to preserve my inheritance»). One more respondent was enthusiastic about the topic and stated that «one could sell accounts of deceased celebrities at auctions. Surely many wealthy fans will be interested in this».

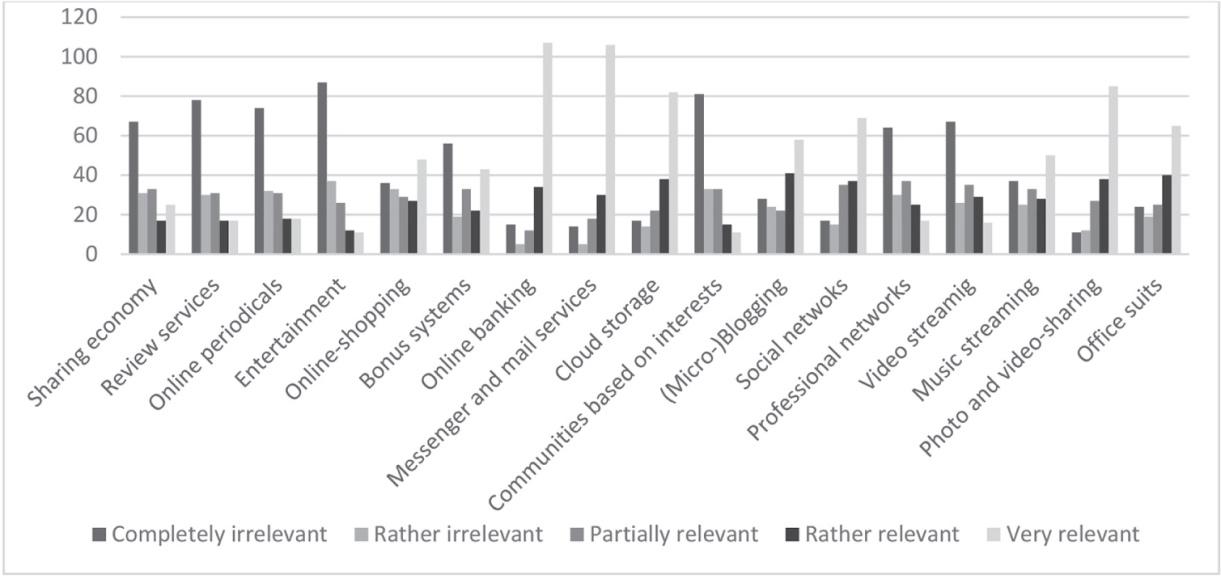

Only 14 respondents have stated that have already heard about digital inheritance; 37 more made assumptions what digital inheritance could mean. The most common answers relate to the inheritance of accounts on social networks, any kind of information stored in digital format, as well as user information on the Internet. 77 respondents stated that they «rather agree» that digital inheritance is the relevant issue nowadays, 36 more «strongly agreed» with the same statement. This means that more than a half of respondents tend to believe that digital inheritance is an important topic. Furthermore, respondents were provided with the table of different categories of services and were asked to estimate the relevance of each category for the inheritance purpose on a 5-point Likert scale. Figure 1 displays the results.

Figure 1: Distribution of relevance of online services with the purpose of inheriting (Source: Own Illustration)

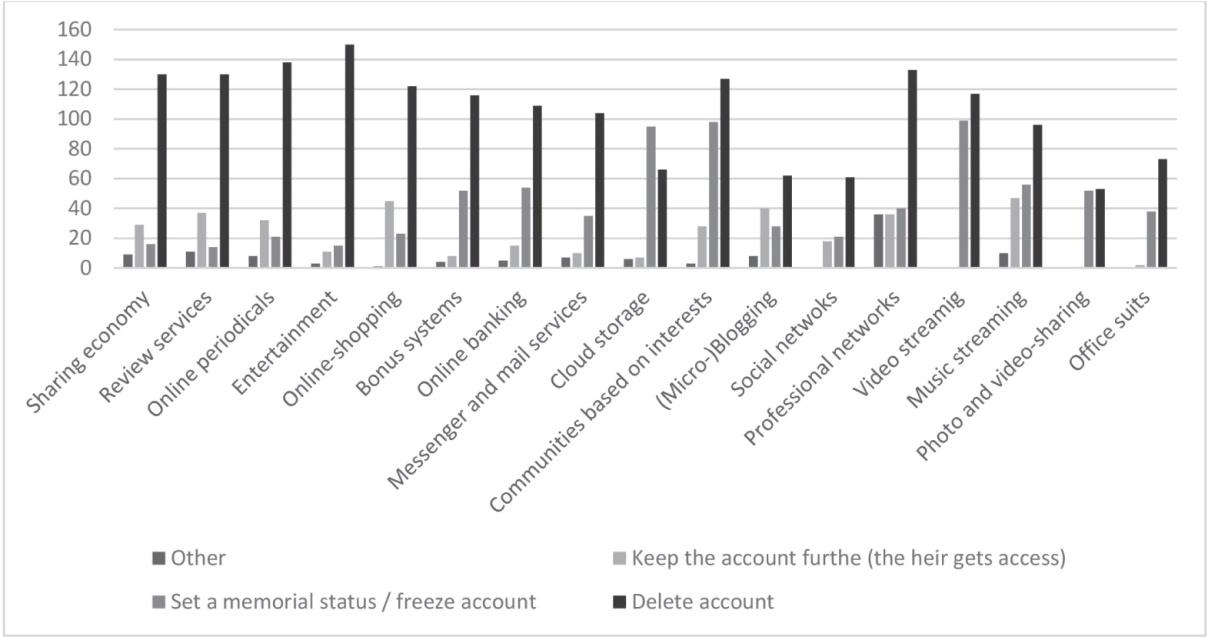

For the respondents, the most interesting and important categories by degree of importance are: online banking and online money, messenger and mail services, photo and video-sharing services, cloud storage, social networks, office suits and (micro-)blogging platforms. The respondents are mostly indifferent to such services as (by degree of irrelevance): entertainment platforms, communities based on interests, review services, online periodicals, video streaming and professional networks. After that, the respondents were again provided with the same list of services and were asked to say what do they wish to happen to their accounts of these categories after they die. The following options of aftercare were suggested: delete account, turn account into a memorial, or let the heir get access and keep the account further. In case the respondents were not satisfied with the proposed options of aftercare, they could choose «other». Figure 2 represents the preferred digital legacy aftercare options.

Figure 2: Distribution of preferred measures regarding own digital legacy (Source: Own Illustration)

For the 16 categories, the most popular aftercare option is the permanent account deletion. The only one service category where the desire to memorialize account prevails over the desire to delete it is cloud storage. The least popular option is providing the heir with access to account. There are only 5 service categories where respondents prefer bequeathing account over memorializing it: (micro-)blogging, online-shopping, online periodicals, review services and sharing economy, although the last three categories were estimated to be irrelevant to digital inheritance.

The results of the survey have shown the Runet users’ interest in digital inheritance, but due to lack of information and regulation options only a few people are familiar with the topic and have settled own digital legacy. Since most of popular in Russia services do not provide any precaution options, many people have never before wondered about the regulation of digital inheritance. The survey has led more that eighty percent of respondents to think about digital inheritance.

The last question in the survey was aimed at the respondents’ opinion on the regulation of digital inheritance – should inheritance be regulated by the state or at the discretion of online services? Collected opinions split almost in half: 52.60% stand for the legal regulation and 47.40% for the regulation at discretion of online services. This encouraged us to offer two solution models, each of which would satisfy the interests of one of the halves.

6.

Solution models for Digital Inheritance in Russia ^

As the results of the previous chapters have shown, there are neither legal framework, nor integrated in the services precaution and aftercare options. The purpose of the model is to provide Runet users with the opportunity to settle own digital legacy and make sure that their accounts will not be left abandoned and every sensitive and confidential data stay secure.

We propose two models – one with the involvement of the government and one without the involvement of government. Both of the models are represented below.

6.1.

A model with the government involved ^

For the basis of this model we took a model proposed by Nellius et al. (2019, pp. 41–45). The model provides for the existence of a trusted intermediary portal between users and service providers. The user settles his or her will in the service provider’s settings and undergoes an identity verification on a portal, providing the portal with the needed information about account on the service. The portal is maintained by the state and in the event of a citizen’s death, a death certificate is obtained. The portal subsequently finds information about the accounts that the citizen has registered in the portal and transmits information on the death of the user to the corresponding service providers. Finally, service providers check the pre-settled «digital will» and performs the account activity that the deceased wished.

In the Russian Federation, there is already an e-Government portal that has all the forces and capabilities to implement such a model – GosUslugi. To register on the portal, verification is required, during which the citizen first enters all the necessary data online, and then comes to the offline office and confirms his or her identity with passport. GosUslugi has a wide range of services: online payment of fines, taxes and utilities, paperwork for a car, labor law consultation, general health insurance information, information from library collections and many more. GosUslugi perfectly fits in the model proposed by Nellius et al. (2019)for the application in Germany. However, this model does not consider two details. First of all, a lot of users prefer to remain anonym when using certain online services. By confirming the identity using the e-Government portal, the user loses its right to remain absolutely anonym. Secondly, users create accounts on various services among the World Wide Web, and many services are based in different countries. The proposed model may work without obstacles with services that obey the same (in this case – Russian) legislation, but on the international level problems may occur. For example, Twitter and Facebook do not have a representative in Russia and are not obliged to follow the letter of the law of a foreign country. This contradiction remains to be resolved.

6.2.

A model without involvement of government ^

The development of this model was inspired by the interview with one of the experts. While discussing the previous model, the expert stated that in his opinion, insurance could solve the problem of digital inheritance. The digital legacy settlement procedure could be as follows: in case a user values some of his or her accounts, he or she contacts insurance company and concludes an account insurance contact in case of his death. Insurance company, in turn, undertakes to fulfill the client’s request after his or her death. Service providers participating in such a model also have their own interest – a monetary one. The user makes regular payments for insurance, in exchange for which the insurance finds an agreement with the service providers; the insurance-service agreement is also binded on the monetary basis: the service provider accepts the conditions of the insurer and undertakes to fulfill them.

However, there are few issues with this solution. Firstly, the above described service does not correspond to the definition of the insurance to provide a guarantee of compensation for, say, specified loss, damage, illness, or death. It cannot be assumed that the digital heritage will always be accompanied by material damage to the policyholder. Second, if the general terms and conditions of a social network or other online service prohibit the disclosure of access data to third parties, the disclosure to any such insurance companies would also be excluded. Exception: such a possibility or exception would be explicitly included in the general terms and conditions.

7.

Conclusion ^

The introduction of digital rights into Russian legislation has opened new field of scientific research. The aim of our study was to give an overview of the situation in the Russian Federation regarding digital heritage and related challenges and to discuss possible solutions for user-oriented management. Our research shows that, apart from legal obstacles, only a few online services currently have a degree of digital heritage functionality. Lack of information also slows down the possible development of the concept. The results thus generally suggest that digital inheritance is still in its infancy and needs more discussion and investigation to support and promote its development.

In a further step, the survey of Internet users showed that a fundamental interest in the subject can be assumed. However, there is still a need for more intensive awareness raising in order to draw more attention to the importance of the digital estate for the users themselves and their potential heirs. One surprising finding for us was the strong aversion of some respondents to the issue of death. Previous studies do not seem to have made observations on a comparable scale, which suggests a cultural peculiarity. Furthermore, the results show that users have different expectations of inheritance functionalities for different categories of online services. For example, financial services, communication services, online storage, and photo and video platforms were particularly relevant for inheritance. In addition, there were different statements on how the respective profiles and data are to be inherited. It cannot be ruled out that users might expect different functionalities even within special online services and want to decide how to deal with different components of a service. For example, social networks often not only have the option of communication, but also of exchanging photos and videos, and in the future, as the example of Facebook shows, they may also have payment options. A uniform or comprehensive regulation obliging all online services to offer identical functionalities would in all probability contradict this expectation, so that the approaches outlined in this paper also have a limitation. For further research, it is advisable to investigate the situation in further countries to identify possible similarities and differences in the expectations of Internet users in different regions and in relation to different online services. In this way, it may be possible to identify local demands and expectations regarding the services offered by service providers and derive suitable solutions for shaping the digital heritage from a legal and information technology perspective. Furthermore, it could be investigated how the different inheritance offers of an individual online service could be dealt with. Another important aspect that should also be investigated is how different countries approach data protection. With the increase in the amount of digital information on the Internet, the issue of protecting personal data is particularly acute. EU countries obey a GDPR law that has much higher requirements for data operators than a similar law in Russia, while other countries have their own laws, which may not be similar to either EU law or the law of the Russian Federation.

8.

References ^

Brand Analytics. (2018). Социальные сети в России: Цифры и тренды, осень 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2019, from https://br-analytics.ru/blog/socseti-v-rossii-osen-2018/

Brubaker, J. R., & Callison-Burch, V. (2016). Legacy contact: Designing and implementing post-mortem stewardship at Facebook. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – Proceedings, 2908–2919. https://doi. org/10.1145/2858036.2858254

Dr. Leiner, D. (2013). Too Fast, Too Straight, Too Weird: Post Hoc Identification of Meaningless Data in Internet Surveys. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2361661

Google. (2019). Inactive Account Manager. Retrieved September 10, 2019, from https://myaccount.google.com/inactive

Janisch, W. (2018). Erben bekommen Zugriff auf Facebook-Konto. Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Nellius, L., Zepic, R., & Krcmar, H. (2019). Finaler Logout – ein neuer Ansatz für die Gestaltung des digitalen Nachlasses bei sozialen Netzwerken. In E. Räckers, M., Halsbenning, S., Rätz, D., Richter, D. & Schweighofer (Ed.), Digitalisierung von Staat und Verwaltung (pp. 37–48).

Stepanov, V. (2014). завещаю тебе свой логин. TJ. Retrieved from https://tjournal.ru/tech/52084-digital-will

BЦИОМ. (2018). Кaж∂омy воɜрaсmy – своu сеmu.

ГК РФ Сm. 1112. Haсле∂сmво. (2019).

ГК РФ Сm. 128. Объекmы гражданских nрaв. (2019).

ГК РФ Сm. 141.1. ЦuФровые nрaвa. (2019).

КодАчигов, B. (2018). Cамые популярные в России мессенджеры – WhatsApp, Viber и Skype. Retrieved September 10, 2019, from Bедомости website: https://www.vedomosti.ru/technology/articles/2018/09/17/781109-samie-populyarnie-v-rossii-messendzheri

Консмuмyцuя Россuŭскоŭ Фе∂ерaцuu. Сm. 23. (2019).

Фе∂ерaльныŭ ɜaкон оm 18.03.2019 N 34-ФЗ. (2019).

Фе∂ерaльныŭ ɜaкон om 27.07.2006 N 152-ФЗ (ре∂. om 31.12.2017) «О nepcoHonbHbix ∂aнныx.» (2006).

Шатилина, A. (2015). «Цифровое наследство» – настоящее или будущее? Инмеллекмyaльнaя Собсмвенносмь. Aвморское Прaво u Смежные Прaвa, 9, 74–79.