1.

Introduction ^

The problem explored in this article is the change in the significance of the law in the digital era and the emergence of new moral standards. The law, as a partially social function, is subject to continuous change, not only in terms of content, but also in terms of its importance. This also includes legal dogmatics and legal theory as meta-levels of law, and recently also legal informatics, as has been developed in the framework of IRIS conferences, for example.

The current model of the state goes back to two concepts, among others: first, sovereignty (Bodin, Hobbes) and, second, since the nineteenth century, the rule of law. The concept of sovereignty underwent a change in the European area when the European Union transferred components of the previous state sovereignty to the Union. On the other hand, through decades of refinement of the legal system, the rule of law has reached a state that can be described as “mature”. Both the transfer of sovereignty and the perfected rule of law, however, point to further paradigm shifts. Some of these have already occurred.

Figure 1: Positive law and new normative standards in the digital context

The change from conventional textual media to digital electronic media is evident in the law. This is not only the case for information about the law; it also goes deep into the decision-making mechanisms of the law. In the medium term, the structure of the state will also be changed, as electronically-based, algorithm-controlled government cannot be equated with the previous personally-designed state powers. New normative standards can be placed beside positive law (Figure 1).

In addition, there has for several years been a content-related, extra-legal trend that initially ran alongside and then also rivaled the law, namely, new norms of political correctness. The relationship between law and morality (which also includes natural law) has been an issue for about 150 years, and was finally clarified in terms of the separation thesis (see [Kelsen1967, 1992]). The new moral standards approximately fill the gap that has arisen as a result, albeit in a different way.

There are different effects on the law. First, the new perspectives can affect the interpretation of the law. The result is then legal acts whose content is influenced by non-legal standards. Second, it is also conceivable that the new norms will take effect directly as primary norms as well as secondary norms (sanctions). New figures of identification will emerge, to which the heads of state will bow down.

The new normative standards are still being developed openly. The old natural law has disappeared, but nature itself is becomming the standard of the new Ought here, as is clear, for example, in the ecological movement. From the nature of the human being, which is being reinterpreted, a new typology of images of human beings is derived, and this has already been adopted to some extent by the legal system.

The digital context of the new standards is multifaceted. As far as digital access to the relevant texts is concerned, this applies more to factual information. Formal systems of normative information are still a long way off, and are perhaps not very realistic at all. The reason is that the summarizing texts of the new standards designed in detail is still rare. The stage of a comprehensive codification, and thus electronic access to it, is far from being reached.

What seems remarkable, however, is the impact of these new standards on the virtual world (including electronic virtuality, “e-...”, and cyberspace). The law has stayed out of this area. There were certain aspects of the content of plays and films that were beyond the scope of the law. The Middle Ages tried to influence this virtuality with the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (“List of Prohibited Books”), but the rule of law, with its understanding of freedom of expression and freedom of art, protected these spaces, not even entering them.

It is interesting that now the new morality is not keeping to these limits, just as in earlier times morality did not see the law as a limit, but rather as a challenge (Antigone). The scope of the new standards also tends to extend into e-virtuality, as can be seen from the fact that a leading entertainment publisher has withdrawn products that are no longer compliant. Digitality therefore brings not only a paradigm shift for legal norms, but also a paradigm shift and the opportunity for a new development with moral norms influencing the law. This is an aspect that modern legal theory had already seen as overcome.

Transformation of the law. The transformation of the law under information-technological conditions [Karavas 2009] is discussed in the literature; see, for example [Brownsword/Yeung 2008, Hildebrandt 2015, Hildebrandt/O’Hara 2020, Graber 2021]. Vaios Karavas [Karavas 2009, 464] argues that “the emergence of the computer as medium has triggered a transformation of the legal sphere that is culminated [sic] in the emergence of a techno-digital normativity that seems to undermine Luhmann’s description of the legal system as an autonomous social system.” The risks introduced by computers, and the dangers of artificial intelligence (AI), can be viewed both from the perspective of programming and from the perspective of law; see, for example [Graber2020 ]. Christoph Graber formulates recommendations to avoid the dangers, in relation to fundamental rights, of platforms using AI.1 Mireille Hildebrandt [2015, 214] develops the concept of “legal protection by design” (LPbD), and writes about the transformation of the law.2 Certain “rule of law” implications of Big Data analysis from a techno-regulatory perspective are identified by Bayamlıoğlu and Leenes [2018]. They write about “(i) the collapse of the normative enterprise, (ii) the erosion of moral enterprise and (iii) replacing of causative basis with correlative calculations.” The emergence of new technologies such as AI, the Internet of Things (IoT) and robotics poses new risks, and there are specific concerns regarding AI systems (see e.g. [EC 2020] for the requirements for trustworthy AI).

2.

Formation of law and morality ^

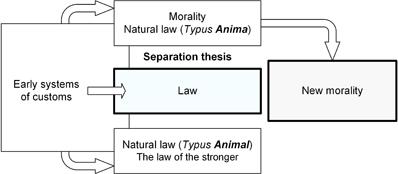

Our departure point is a customary law system of an early society which is governed by a system of customs (see the left-hand section of Figure 2). Law as a core social system develops through the ages. Morality, that is the natural law of typus anima (related to spirit and the positive morality of rational man), develops in parallel (see the middle and the top sections of Figure 2). Next comes the separation thesis. This states that law and morality are separate systems (see e.g. [Kelsen 1967]). Next emerges the “new morality” (see the right-hand section of Figure 2). The new morality regulates the correctness of political and speech behaviour as well as new values.

Figure 2: Development of law, morality and the new morality

The natural law of typus animal (the law of the strong) should be not forgotten. The two kinds of natural law, typus anima and typus animal, can be illustrated with examples from classical antiquity. Nowadays the new morality reaches the cyberspace and shapes the constellation that comprises the two kinds of natural law, typus anima and typus animal.

The matters of new morality are mostly delicate, awkward or taboo; see, for example, the work of Čyras and Lachmayer [2018]. Examples are “me too”, the media depiction of people (particularly women), and indications of country of origin.

3.1.

A scheme of the normative hierarchy ^

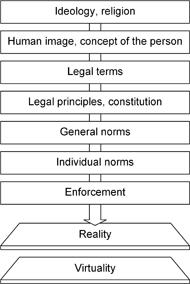

A scheme of the normative hierarchy is shown in Figure 3. This scheme of legal hierarchy is a model and has a limited range. Different models are conceivable. The scheme is linear and reminds us of the decimal classifications that were used in the early 1970s to order terms. The structure of the legal system (a linear vertical hierarchy) has shaped legal awareness because of its clarity. The structure can be shaped in different ways; see, for example, a discussion on the pyramid of law [Van Hoecke/Ost 1993, Ost/van de Kerchove1999 ]. The model can also be even more complex and represented in multidimensional space.

Ideology, religion. Kelsen opposes ideology. According to him, jurisprudence only has the quality of “science” if it is “pure”, that is, free from ideologies. This opposition by Kelsen was interesting as a thought experiment, but its development went beyond that. The new normative standards show exactly that ideological assumptions influence the content of norms. Into the desired vacuum of ideological purity, undesired content can flow.

Figure 3: A scheme of the normative hierarchy

Human image, conception of man, and human nature. There are different theories of the human image. The concept of the person or, in other words, the understanding of what it means to be a human being, was emphasized by the natural law, but rejected by Kelsen. However, it was the basis of human rights, and has now fully asserted itself. The question is: which image of man? There is also such a thing as image colonialism, in which one human image dominates the others. Image can be enforced using, for example, soft power such as movies. Hollywood films are brought to Europe, but Bollywood films are not brought in the same way. A change in the image of man is currently taking place in the area of gender, not only as regards male or female, but also as regards gender-indifference. The linguistic representation of people’s origins is also a consistent topic. Old Walt Disney has, as a result, withdrawn several films as no longer correct.

Legal terms. This layer makes an analogy with Begriffsjurisprudenz (the jurisprudence of concepts) in the nineteenth century and thesauruses as well as the legal ontologies of the present, and puts an emphasis on a situational treatment of law in addition to a normative one. Legal terms are central in Roman law. We should also mention Raimundus Lullus,3 as well as alchemy. Subsequently Copernicus, Kepler and Galilei did the bridging work, which could be seen as the coupling of the concept engine, and then things have moved on. Besides the tradition of textualists (Plato, Aristotle, Kant, Hegel), the layer of legal terms can be associated with the tradition of geometry.

Legal principles was a research issue in legal theory in the 1970s and 1980s. Legal principles are elastic, whereas legal norms are stricter. Legal principles dominate in the formulations of human rights and constitutions. Legal principles lie in a layer between legal terms and general norms. Legal terms imply no, or a very implicit, Ought, whereas norms imply a strict Ought.

The three subsequent layers – general norms, individual norms, and enforcement – are classical layers of law. They form the core of law and are well described in the legal literature.

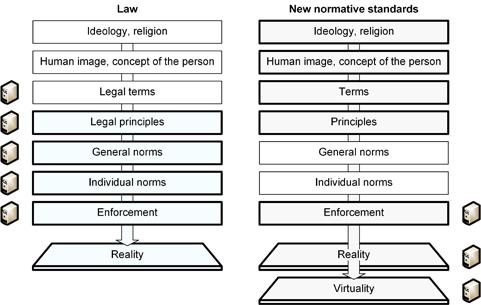

Figure 4: A comparison of the significance of law and new normative standards in the digital context

Reality. Social reality is the target area of law. Kelsen uses the word Is. Forum externum is the target of the law, whereas forum internum is the target of religion.

Virtuality is basically not a target area of the law. Consider the content of books, films and art. This kind of virtuality is not identical to reality or what is in our heads. It is not a target of law. The same is true of electronic virtuality, including the content of computer games, three-dimensional online virtual worlds such as SecondLife, and MMOGs (massively multiplayer online games). However, in ideologically intensive societies, virtuality may become the target of law. Consider religion in the Middle Ages and the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. The situation seems to be changing what is protected by freedom of expression and art. In the new normative standards in the digital context, however, electronic virtuality is becoming a subject of regulation in the moral area.

Electronic virtualities (e-virtualities). In the evolutionary step from humans to machines, the evolution of spiritual spheres can also be observed. We can see the line of spiritual evolution from animism to magic to religion to e-virtuality. Technologies like television, which can be viewed as both macrocosm and microcosm, enable old animistic and magic dreams; for instance, an image projector can imitate the cave paintings of Altamira [Čyras/Lachmayer 2020].

There are several reasons to explore virtuality in its multiple senses. Virtuality is natural to society. First, there are illusionary worlds, for example the three-dimensional virtual worlds. Secondly, unconscious (unconscious phenomena of different types) and abstract entities can be investigated with scientific methods. The worlds of the ego and the id are investigated here. Next, cybergovernance moves real-world activities to cyberspace such as computerized virtual worlds. E-government applications enable legal machines to perform functions of the state. Finally, the militarization of the state seeks enemies. The notion of external enemies is supplemented by the notion of internal enemies, and propaganda wars are carried out alongside virtual wars.

Losing touch with reality. Electronic virtualities introduce the risk of losing touch with reality and failing to see the horizon. This is also the case for virtual worlds and computer games. Here, the reader may recall the allegory of Plato’s Cave. What is reported in the press, on television and through social networks can be compared with the shadows that are projected onto the wall of the cave; these shadows form the reality for the watchers, but are not accurate representations of the real world. Nowadays, the risk of losing control over reality and of living in an illusory reality has emerged.

3.2.

Comparing the law and the new normative standards ^

Let us apply the scheme of the normative hierarchy above in order to compare the significances of the law and the new normative standards. In the digital context, the law is significant in only four layers: 1) legal principles and constitutions, 2) general norms, 3) individual norms, and 4) enforcement (see the left-hand section of Figure 4). The law affects significantly reality, but not virtuality. The new normative standards are significant in more layers (see the right-hand section of Figure 4, and the layers in bold type). Both reality and virtuality are affected.

Conclusion. The content and the importance of the law change constantly. This change also affects legal dogmatics, legal theory and legal informatics. The textual media of the law and decision making is shifted to digital electronic media. E-government applications change the previous personally-designed state powers to algorithm-controlled ones. New normative standards emerge and approximately fill the gap between positive law and morality. The first effect is that the interpretation of the law changes. The results are legal acts influenced by non-legal standards. Second, it is also conceivable that the new norms will take effect directly. The scope of the new standards also tends to extend from reality into e-virtuality.

4.

References ^

Brownsword, Roger/Yeung, Karen (Eds.), Regulating Technologies: Legal Futures, Regulatory Frames and Technological Fixes. Hart Publishing, Oxford 2008.

Bayamlıoğlu, Emre/Leenes, Ronald E., Data-Driven Decision-Making and The ‘Rule of Law’, Tilburg Law School Research Paper, 1 June 2018. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3189064.

Čyras, Vytautas/Lachmayer, Friedrich, Legal Taboos. In: Schweighofer, Erich et al. (Eds.), Data Protection/LegalTech: Proceedings of the 21st International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2018, Editions Weblaw, Bern, 2018, pp. 419–426, Jusletter IT, 22 February 2018. DOI: https://doi.org/10.38023/e8b95dec-e469-4686-b06b-1400dfc4fd4c.

Čyras, Vytautas/Lachmayer, Friedrich, Legal Visualisation in the Digital Age: From Textual Law towards Human Digitalities. In: Hötzendorfer, Walter/Tschohl, Christof/Kummer, Franz (Eds.), International Trends in Legal Informatics: Festschrift for Erich Schweighofer, Editions Weblaw, Bern 2020, pp. 61–76.

EC: Assessment List for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence (ALTAI) for Self-assessment. European Commission 2020. DOI: 10.2759/002360, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=68342.

Graber, Christoph B., Artificial Intelligence, Affordances and Fundamental Rights. In: Hildebrandt, Mireille/O’Hara, Kieron (Eds.), Life and the Law in the Era of Data-driven Agency. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham 2020, pp. 194–213. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788972000.00018. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3299505.

Graber, Christoph B., How the Law Learns in the Digital Society, Law, Technology and Humans, volume 3, issue 2, 2021, 12–27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5204/lthj.1600.

Hildebrandt, Mireille, Smart Technologies and the End(s) of Law. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham 2015, 296 pages. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781849808774.

Hildebrandt, Mireille/O’Hara, Kieron (Eds.), Life and the Law in the Era of Data-Driven Agency. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham 2020. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788972000.

Karavas, Vaios, The Force of Code: Law’s Transformation under Information-technological Conditions, German Law Journal, volume 10, issue 4, 2009, pp. 463–482. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S2071832200001164.

Kelsen, Hans, Pure Theory of Law, 2nd Edition (trans: Knight, M.) University of California Press, Berkeley 1967.

Kelsen, Hans, Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory. A Translation of the First Edition of the Reine Rechtslehre or Pure Theory of Law (trans: Litschewski Paulson, Bonnie/Paulson, Stanley L.) Clarendon Press, Oxford 1992.

Ost, François/Kerchove, Michel van de, Constructing the Complexity of the Law: Towards a Dialectic Theory. In: Wintgens, Luc J. (Ed.) The Law in Philosophical Perspectives. Law and Philosophy Library, volume 41. Springer, Dordrecht 1999, pp. 147–171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9317-5_6.

Van Hoecke, Mark/Ost, François, Epistemological Perspectives in Jurisprudence, Ratio Juris, volume 6, issue 1, 1963, 30–47. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9337.1993.tb00136.x.

- 1 Graber begins with the observation that “[t]he expansionism of giant platform firms has become a major public concern, an object of political scrutiny and a topic for legal research. As the everyday lives of platform users become more and more “datafied”, the “power” of a platform correlates broadly with the degree of the firm’s access to big data and artificial intelligence (AI)” [Graber 2020]. Graber writes about the affordances (the possibilities and constraints of a technology) and concludes with four recommendations concerning AI.

- 2 Hildebrandt [2015, 214] argues that: “without LPbD we face the end of law as we know it, though – paradoxically – engaging with LPbD will inevitably end the hegemony of modern law as we know it. There is no way back, we can only move foreword. However, we have different options; either law turns into administration or techno-regulation, or it re-asserts its ‘regime of veridiction’ in novel ways.”

- 3 Lullus invented a philosophical system known as the Art, conceived as a type of universal logic to prove the truth of Christian doctrine to interlocutors of all faiths and nationalities. The Art consists of a set of general principles and combinatorial operations. It is illustrated with diagrams; see Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramon_Llull.