1.

Introduction ^

The hybrid theory has been presented as a combination of a standard model of causal-abductive reasoning (e.g. [7]) and an argumentation framework in the style of [9]: observations are explained by hypothesised causal rules and facts (e.g. observing smoke we hypothesise fire and the rule fire causes smoke) and these hypotheses can be supported or attacked using arguments (e.g. Bob said «I saw a fire» so fire or Wilma said «I did not see a fire» so fire or fireman Sam says «Fire can cause smoke» so fire causes smoke). This formalisation of the hybrid theory draws inspiration mainly from «rule-based» approaches in AI and Law, in particular [10]. This is not just evident in the hybrid theory’s modelling of supporting and attacking arguments but also in the style in which it models stories (i.e. as networks of causal rules).

Integrating the hybrid theory into the CBR approach can also enhance existing work on CBR. This work has mostly concentrated on legal reasoning (that is, reasoning with legal cases and only considering facts which are directly legally relevant) and the specific facts of a case, the stories about these facts and the reasoning with these facts have not been explored in detail. Furthermore, [15] has argued that the hybrid theory’s concept of story schemes (abstract scenarios that can serve as a scheme for particular stories) can be used to identify, analyze and evaluate arguments from analogy, and show their function in CBR where precedents are involved.

2.

Case Based Reasoning in AI and Law ^

The leading CBR systems in AI and Law are HYPO [2] and CATO [1]. We will base our approach to CBR on CATO (cf. also [3][8][11]).

The key idea of CATO is that cases can be described as collections of factors1. A factor is a stereotypical fact situation that has legal relevance, such as bribed-employee, information-disclosed-in-negotiations, information-reversed-engineered, plaintiff-tooksecurity-measures and the like. The facts of the case determine whether particular factors are present or absent from a case. If present, the factors provide a reason to decide for either the plaintiff or the defendant. Thus bribed-employee and plaintifftook-security-measures are reasons to find for the plaintiff, and information-disclosedin-negotiations and information-reversed-engineered are reasons to find for the defendant in a trade secrets case. Typically a case will contain a number of factors, some favouring the defendant and some favouring the plaintiff, and the court will need to decide which set of reasons prevail.

As HYPO, CATO supports a three ply form of argument:

- One side cites a precedent case (a case with factors in common with the current case) decided for their side;

- Other side presents counter examples (cases with factors in common decided for the other side) and distinguishes the cited cases;

- Original side may distinguish the counter example, and cite any additional reasons to support their side.

Whereas the dimensions of HYPO are independent, CATO arranges the factors in a hierarchy where the base level factors are reasons to decide that a more abstract factor is present or absent. Thus if information-improperly-obtained is an abstract factor (favouring the plaintiff), bribed-employee is a reason to think it present while information-disclosed-in-negotiations and information-reversed-engineered are reasons to think it absent. Factors belonging to the same abstract factor may be substituted for one another (if their polarity is the same) or cancel one another (if the polarity is different). This enables distinctions to be downplayed by cancelling a factor, or by substituting a factor in the precedent but not the current case by one in the current case but not the precedent.

3.

The hybrid theory for Inference to the Best Explanation ^

The hybrid approach combines stories and arguments in a framework for abductive Inference to the Best Explanation (IBE) [4][5][6]. In IBE, we have a set of observed facts which have to be explained by a hypothesis. In other words, given a set O of observations and the knowledge that hypothesis H explains O, we infer that H is probably the case. A hypothesis can take the form of a story, a chronological sequence of states and events that forms a coherent whole. Arguments are used in the hybrid theory as the basis for the observations: every element of O is the conclusion of an argument (usually based on evidence) that is part of the hybrid framework.

In IBE it is imperative that we also consider alternative hypothetical stories that explain the observations, and these stories will then have to be compared. In this comparison, it is not only important that a story conforms to the evidence but also that a story is coherent.2 Generally, we say that a story is coherent if it conforms to the way we expect things to happen in the world. This means not only that a story should be consistent, but also that it should be anchored in plausible common-sense knowledge of the world [14]. For example, a story where a man enters a restaurant, orders a hamburger, receives his hamburger from the waiter, removes his pants and offers the waiter his pants in exchange for the hamburger can be considered incoherent and hence implausible3: people do not normally remove their pants in restaurants, nor do they offer their pants as barter for food.

3.1.

Precedents in factual reasoning ^

The question now is how to find valid, plausible story schemes. Story schemes ideally model the way things tend to happen in the world. This means that the plausibility of story schemes depends on precedent stories: the restaurant scheme we use is based on our experiences of restaurants, and none of the authors ever had a strange experience like the one described above. Here, a precedent is an instance of a story scheme, and so can help to establish the validity of the story scheme as a determinant of global coherence. Furthermore, in realistic contexts people will usually find it more effective to cite a precedent story rather than an abstract story scheme.

As an example, suppose two people meet on a train: on one story it is a chance encounter, in another it is an arranged meeting. If both people regularly use the train at similar times a chance meeting is entirely plausible. If they rarely use the train, or live elsewhere, it is less so. But citing a particular story can help, particularly a personal one: you remember when you met Bill on the Rialto bridge? Neither of you knew the other was in Venice, but these coincidences do happen. The object here is to establish from personal experience that the improbable actually does occur from time to time, so the coincidence is at least possible. An appeal to personal experience or an appeal to a well-known story is much more powerful than citing a story scheme for chance encounters: A is at location L for reason RA – B is at location L for reason RB – RA and RB are unrelated – A and B meet. The real story provides a unity to elements which would remain entirely disconnected in the abstract scheme.

Citing a similar story thus helps establishing coherence. Here, it is important that the current story and the supporting example be relevantly similar: that is, it can explain similar observations (relevance) and resist attempts to distinguish it (similarity). As [15] argues, we would want the story and the precedent to be an instance of the same story scheme: the chance meeting on the train and the meeting with Bill are both instances of the scheme for chance encounters. If we cannot find a precedent story which matches on enough facts, we can attempt to find a more general precedent (e.g. citing a story which contains a coincidence but says nothing about chance meetings). However, in such a case it is easier to reduce the force of the example by pointing to relevant differences. These distinctions can then be emphasised and downplayed, and so we suggest that precedent stories can be selected, attacked and justified using techniques from CBR, which is itself centrally concerned with identifying relevant similarities and differences.

4.

Incorporating Factual Reasoning into CBR ^

4.1.

Stories, story schemes and cases ^

CATO’s cases are very similar to story schemes. Story schemes are clusters of abstract facts, narrative units, and cases are clusters of legally qualified abstract facts, factors. In other words, the factors represent what we call the legal roles that facts in a story can play. Here, we distinguish between a specific case and a general case with factors. An example of a general case is [Defendant killed Victim, Defendant intended to kill Victim, Defendant killing Victim was premeditated]; a specific case is not a scheme but rather an instantiated «legal story», e.g. [T killed G, T intended to kill G, T killing G was premeditated]. Facts in a story can be matched to the factors in a case in the same way as they are matched to the narrative units in a story scheme, namely through a combination of variable instantiation and rules. For example, an abstraction rule if T stabs G and stabbing injured G and G died then T killed G can be used to match the story to the Defendant killed Victim factor in the case.

4.2.

Argument Moves and Precedents ^

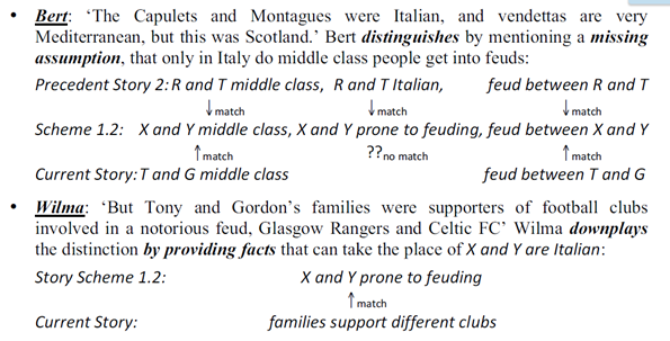

Emphasising the significance of a distinction: this move accompanies a distinction and attempts to pre-empt any attempt to downplay; it seems as much rhetorical as logical.

Downplaying the significance of a distinction: Downplaying a distinction has variants according to the nature of the distinction. If the distinction is an unsatisfied assumption, it is necessary to point to some fact in the current story which can play a similar role, thus having the current story complete the story scheme after all. If the current story has what appears to be an exception, downplaying involves finding a fact in the current story that provides an exception to that exception.

4.3.

An example of CBR with stories and precedents ^

5.

Conclusions and future work ^

6.

References ^

[1] V. Aleven. Teaching Case Based Argumentation Through an Example and Models. PhD Thesis, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1997.

[2] K. D. Ashley. Modeling Legal Argument. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1990.

[3] T.J.M. Bench-Capon and G. Sartor. Theory based explanation of case law domains. In Proceedings of the 7th ICAIL, St. Louis, USA (2001), 12– 21, ACM Press, New York.

[4] F.J. Bex, Arguments, Stories and Criminal Evidence: A Formal Hybrid Theory, Springer, Dordrecht, 2011.

[5] F.J. Bex, P.J. van Koppen, H. Prakken, B. Verheij, A Hybrid Formal Theory of Arguments, Stories and Criminal Evidence. Artificial Intelligence and Law 18:2 (2010), 123–152.

[6] F.J. Bex, B. Verheij. Legal Shifts in the Process of Proof. Proceedings of the 13th ICAIL, Pittsburgh, USA (2011), 11–20, ACM Press, New York.

[7] L. Console and P. Torasso, A spectrum of logical definitions of model–based diagnosis, Computational Intelligence 7:3 (1991), 133–141.

[8] J. F. Horty. Reasons and precedent. Proceedings of the 13th ICAIL, Pittsburgh, USA (2011), 41–50, ACM Press, New York.

[9] H. Prakken, An abstract framework for argumentation with structured arguments. Argument and Computation 1 (2010), 93–124.

[10] H. Prakken and G. Sartor, A Dialectical Model of Assessing Conflicting Arguments in Legal Reasoning. Artificial Intelligence and Law 4 (1996), 331–368.

[11] H. Prakken and G. Sartor. Modelling reasoning with precedents in a formal dialogue game. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 6 (1998), 231–287.

[12] V. Propp, The Morphology of the Folktale, University of Texas Press, Austin (TX), 1968.

[13] R.C. Schank and R.P. Abelson, Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding: an Inquiry into Human Knowledge Structures, Lawrence Erlbaum, New Jersey, 1977.

[14] W.A. Wagenaar, P.J. van Koppen, H.F.M. Crombag, Anchored Narratives: The Psychology of Criminal Evidence, St. Martin’s Press, New York (NY), 1993.

[15] D. Walton, Similarity, precedent and argument from analogy, Artificial Intelligence and Law 18 (2010), 217–246.

[16] A.Z. Wyner and T.J.M. Bench-Capon. Argument Schemes for Legal Case-based Reasoning. Proceedings of the 20th Jurix, Leiden, the Netherlands (2007), IOS Press, Amsterdam.

Floris Bex, corresponding Author. School of Computing, University of Dundee, UK. florisbex@gmail.com.

Trevor Bench-Capon. Department of Computer Science, University of Liverpool, UK.

Bart Verheij. Department of Artificial Intelligence, University of Groningen, The Netherlands.

This article is republished with permission of IOS Press, the authors, and JURIX, Legal Knowledge and Information Systems from: Kathie M. Atkinson (ed.), Legal Knowledge Systems and Information Systems, JURIX 2011: The Twenty-Fourth Annual Conference, IOS Press, Amsterdam et al.

- 1 HYPO used dimensions rather than factors, where a dimension has an associated continuous or discrete magnitude. Factors can usefully be seen as points on particular dimensions.

- 2 This coherence is independent from the evidence, as it is general whereas the evidence is specific; only in the absence of specific evidence we use generalised patterns to fill the gaps. Furthermore, less common events must be better justified by evidence in order to be considered in a story.

- 3 We use the terms coherence and plausibility interchangeably: a story is coherent if it adheres to (i.e. is anchored in) plausible common-sense knowledge and being more coherent makes a story more plausible.