1.1.

Reconsidering Administrative Work ^

1.2.

Government as a Realm of its Own ^

1.3.

The Role of Law and Service Knowledge ^

2.1.

Survey on the System ^

As discussed above, a national government acts within many domains: legislation, public action and administration (teaching and research, defence, security, etc…) and justice… These actions must be financed. Within Europe national governments finance their activities through three main sources: value added tax4, personal income tax and company tax. An interesting question is - how can governments use technology to improve the process of collecting theses taxes? The traditional process of collecting income taxes from citizens as well as income and value added taxes from companies involved mailing forms to the interested parties, which they would then complete and return5. When the tax authorities received these forms, they first needed to extract the information that they contained before processing and printing another form6 that informed the citizen or company as to the amount of his taxes.

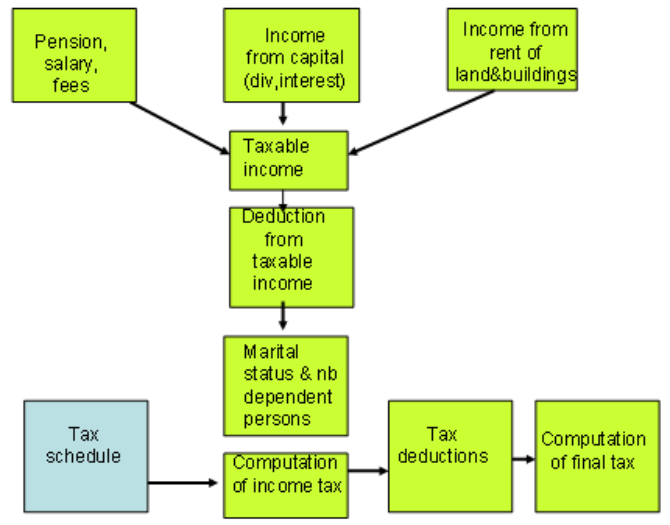

As depicted in the figure, the computation takes three main sources of income into account: salary and/or other income7 (e.g., pensions), income from capital (e.g., interest from loans, dividends from shares), rents generated from land and/or buildings8. Each of these categories is subjected to various automatic9 or conditional parameters. In addition, it is possible to compensate within and between categories10. The sum of these three categories is the income submitted to taxation before deductions11. Applicable deductions12 are then subtracted, and finally this amount is divided by R (a variable which represents the composition and legal status of the household)13. This yields the taxable income to which the tax schedule is then applied. Finally, a long series of possible deductions14 are subtracted from the tax indicated in the schedule, yielding the final income tax due.

It should be noted that two main declaration forms exist: a simplified version is sufficient for citizens who have only salary or pension income and a detailed version for those who have additional forms of income. Furthermore, when income from renting of land and/or buildings exceeds a certain amount, a special form is needed15.

2.2.

Structure and Characteristics of the Application from the User ^

2.3.

Benefits Derived from this Application ^

From the administration’s point of view there is an advantage in terms of cost saving22. Tax personnel, who were responsible for data capture before 2003 are no longer needed and can be used for other tasks, in particular more control of the tax declaration. In fact, the system takes care of many controls, which not only checks computations but also applies a multitude of tax rules, thereby increasing the tax declaration’s reliability. The reduction in the number of paper forms is huge and greatly increases the efficiency of electronic storage and access to the information by all personnel of the fiscal service and by the taxpayer himself.

3.1.

The Basic Idea ^

3.2.

A Challenge for Design ^

3.3.

Desirable Improvements ^

4.1.

Supporting Individual Decision Making ^

Some of these problems originate within the subject domain itself. For example the large number of rules, regulations and case law coming from various sources at global, European, national and local levels make it difficult to model law and legal reasoning. This difficulty is compounded by the fact that legal terms are often not adequately defined for a variety of reasons. Sometimes legal terms are purposefully left vague to allow the possibility of future interpretation. There are also genuine inconsistencies and fuzziness in law. Legal terms can also be left vague to serve the interests of particular bureaucrats or political figures. Legal information retrieval, which has changed little in the past several decades, also poses problems. The key problem is that such systems are still keyword-oriented even thought finding a correct answer typically requires understanding the question, not just knowing the keywords. Case- based reasoning tools offer a possible solution. Prototypes using logical reasoning, including deontic logic, probabilistic methods and neuronal nets exist. However, such systems are experimental. Thus, they belong to the scientific realm and have not achieved large-scale use. An additional complication is that in some cases legal-administrative information must be used by administrations from different states. In these cases, difficulties of interpretation often occur. For example, a classical case is encountered when a European citizen works in multiple European states throughout his career, and ultimately retires in and asks for his pension from yet another state. In this situation, which is faced by an increasing number of European citizens, the pension organisations from the various states must cooperate. Problems also arise when it is difficult to find equivalent legal terms across multiple languages24. This is a common problem in domains such as intellectual property, licensing, certificates and academic degrees. Furthermore, some terms may have different connotations across languages. For example, they may imply different professional boundaries as when considering the activities a of lawyer and a barrister. Sometimes, equivalent terms simply do not exist across languages. For example, this problem is often encountered when considering public honours, awards, and titles.

4.2.

Supporting Group Decision Making ^

4.3.

Adding knowledge-based Components ^

4.4.

Collaborative Platforms and Social Media ^

4.5.

Mobile Government ^

4.6.

Proactive Government ^

Acknowledgment: We would like to thank professor Joseph Lajos for his stylistic comments.

5.

Bibliography ^

Chen, H. et al. Digital Government: E-Government Research, Case Studies, and Implementation. Integrated Series in Information Systems. Springer, New York, 2008.

Michel R. Klein «Supporting Financial Strategy Development in French Towns Using a Financial DSS», Proceedings Information Systems in Public Administration and Law, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft, G. Kirchmayr, R. R. Wagner, M. Wimmer (Eds.), 2000, Austria.

Michel R. Klein: Government Support for Energy Saving Projects. EGOV 2004:

Michel R. Klein , «Internet, Citizen Access to Town Accounting Data and Democracy», Proceedings of the 13th Bled International Conference on Electronic Commerce, June 2000, Bled, Slovenia.

Michel R. Klein , «Decision support for municipality financial planning», Proceedings 2nd IFIP TC 8 Conference on Governmental and Municipal Information Systems, North Holland, R. Traunmüller (Ed.), 1991.

Michel Klein, Leif Methlie, Expert systems, A decision support approach , Wiley 1995

Traunmüller, R., Wimmer, Maria. 2005. Online one-stop Government. Wirtschaftsinformatik 47, Heft 5, S. 383-386

Scholl, J., Janssen, M., Traunmüller, R., Wimmer, M. (eds.). Electronic Government, Proceedings EGOV 2009, LNCS Springer Verlag, Berlin et al. 2009.

Scholl, H. Jochen, Janssen, Marijn, Traunmüller, Roland; Wimmer, Maria A. (Eds.) (2009): Electronic Government: Proceedings of ongoing research and projects of EGOV 09. 8th International Conference. Trauner Druck. Bd. Schriftenreihe Informatik. Nr. 30.

Traunmüller, R. Web 2.0 Creates a New Government (Invited Paper). In: Andersen, K. et al. Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective. Proceedings of EGOVIS 2010, 31 August – 2 September 2010, Bilbao, LNCS 6267, Springer Verlag, Berlin et al. 2010.

Traunmüller, R. and Wimmer, M. Knowledge Management and Electronic Governance, In: Janowski, T. and Pardo, T., (Eds.). Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, ICEGOV 2007, 10 - 13 December 2007, Macao, China. 2007.

Roland Traunmüller, Johannes Kepler University Linz.

Michel R. Klein, HEC, School of Management.

- 1 National governments interact with citizens on many occasions (e.g., collecting data for tax purposes, documenting major events in citizens’ lives, implementing democratic processes such as voting). National government interacts with various levels of local government as well as other state government within or outside the EU.

- 2 Such as deciding on the allocation of public financial support to various categories of citizens ( elderly, unemployed,…) or citizens projects which the gvernment wishes to support ( energy saving…).

- 3 The basic missions in which national governments typically engage include: managing the democratic process (e.g., voting procedures), managing fiscal and financial policy, providing education, funding research, supporting local government, providing defence, supporting employment, supporting solidarity, providing justice, security and police, participating in the EU budget (for EU countries), supporting sustainable development (e.g., ecological initiatives), etc. Furthermore, the national governments of many countries have an additional mission of repaying debt and maintaining it within national and European legal limits.

- 4 In 2011, the French tax authorities collected €272 billions in taxes (€130 billion in VAT, €52 billions in income taxes, €45 billions in company taxes,14,1 billions from energy products (EU directive 2003/96/CE ) and 30 billions from other fiscal taxes.

- 5 Small companies that cannot afford an internal accountant typically hire an outside accountant to complete these forms.

- 6 In French « Avis d’imposition ».

- 7 Such as consulting fees for a doctor, architect or other professional, income of a farmer or

- 8 Income from commercial and industrial activities ( benefices industriels et commerciaux) are not included in this simplified presentation).

- 9 For example, a 10% deduction is applied to salaries whereas a 20 % deduction is applied to pensions, within the limits of a maximum deduction. Furthermore, pensions derived from voluntary savings are themselves factored by the age at which the person decided to liquidate his pension.

- 10 For example, accumulated losses from rent of land and buildings in previous years can be deducted from future profits in the same categories. Furthermore, such losses can, within limits, be deducted from salary or pension income.

- 11 In french « Revenu Imposable ».

- 12 Two typical deductions are alimony and voluntary pension contributions (within limits).

- 13 « Nombre de parts » which depends on marital status (married, bachelor, widowed, etc) and number of dependents.

- 14 Examples of allowed deductions: 60 % of charitable contributions, 50 % of salaries paid to domestic employees, union fees, life insurance, a percentage of investment for energy saving expenses (insulation, heat pumps, etc). The total of these deduction being limited according to the fiscal law (10 000€ for 2012).

- 15 This form enables the taxpayer to submit an income statement (revenues and expenses) for each rented building.

- 16 France is probably one of the last countries in the EU that does not require the organisation generating the income to withhold the income tax (retenue à la source). Companies declare the salaries to the fiscal authorities as well as social charges to the social security administration each quarter.

- 17 Fiscal number of each member of the household, typically the husband and wife, informant number.

- 18 Single, married, PACS (type of partnership non existing in Austria), divorced, …number of dependent persons…

- 19 Salaried person, farmer, independent worker, liberal profession, retired and the fiscal regime adopted.

- 20 The form 2042K for salary and pension income, the form 2044 for rent from land and buildings.

- 21 Resulting from the fiscal law that was passed by the Parliament in the same year.

- 22 The financial return of such an application can be computed using standard financial criteria (eg: net present value). However, it should be recalled that the data capture was not subcontracted, given the confidentiality of the information; it was performed by civil servants who are permanent personnel. This personnel can, however, be used for other tasks.

- 23 Such as the French Service-public.fr.

- 24 For example the partnership called PACS (Pacte Civil de Solidarité) in French as not Austrian equivalent.