1.

Introduction ^

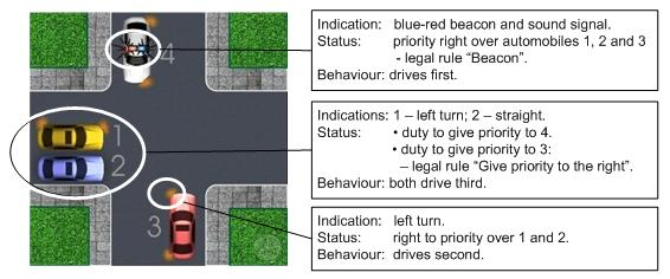

Fig. 1: A sample road situation which is presented to an examinee to take a driving theory test. The examinee has to answer a question. In this situation the question is «Which order does automobile 2 drive?» (Blue-red beacon and sound signal are on 4). The right answer: the third, along with 1.

2.

Characterisation of the Concepts of Situation and Case ^

Situations and cases are characterised differently:

Situations and cases are characterised differently:

- Type. A situation constitutes a generic behaviour pattern whereas a case – a concrete one.

- Ex-ante/ex-post. A situation is related with ex-ante analysis whereas a case – with ex-post.

- Time. A situation concerns the future whereas a case – the past.

- Alternatives.

Situation: alternatives are possible. This is the essence of a situation.

Case: Concrete behaviour. Events are passed.

However, alternatives can appear in hypothetical evaluations such as «Should the actors perform another manoeuvre, the accident would not happen.»

- Language

- A situation is mentally – visually, acoustically, sensibly – interpreted. Suppose a driver in a crossroad (see e.g. Fig. 1). A mental language is non-textual and non-professional. Sensual (visual, aural, etc.) comprehension dominates and textual descriptions appear on the periphery. Hence, a situational language is non-professional. A communication language needs not to be textual; cf. gestures. Therefore a situational language is loosened and differs from case languages.

- Roles are inherent in situations, e.g. «pedestrian», «driver», «pilot». Actors’ legal status may be implicit because rights and obligations are comprised by their roles.

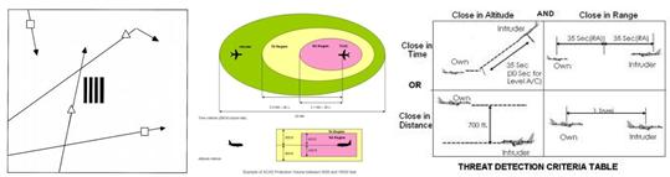

- Artificial agents can use formal languages. As an example suppose multi-agent systems. Agent’s beliefs, desires and intentions are represented in computers in a knowledge representation language.

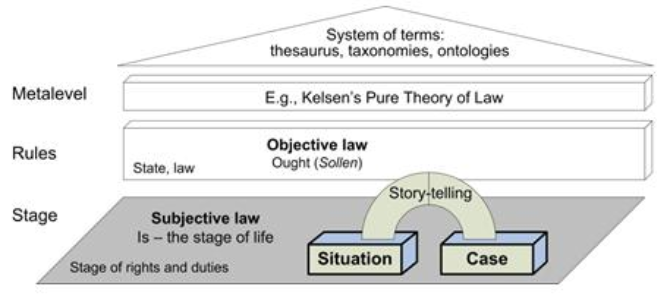

- Placing onto the Is and Ought stages

Situation- i. Situations are assigned to Is. A situation is always real, factual. As an example suppose a crossroad with red light on. You would like to cross but do not want to show children a bad example while they learn the custom law from your behaviour.

- In contrast, the type of a situation is assigned to Ought. A situation type allows visual representations such as a schema. This appears in technical devices.

- Cases are also assigned to Is. Every case has passed. The reference range is not important. A case is fixed in the text.

- A case is on the Is stage but can be viewed from two perspectives. Firstly, the case is assigned to the subjective law. Secondly, the case is assigned to legal proceeding, hence, to the objective law. Here argumentation arises. The players are assigned legal proceeding roles such as plaintiff, defendant, witness, expert, etc.

- Web applications. e-Government application examples in Austria:

Situations see in www.help.gv.at. Cases see in www.ris.bka.gv.at. - Legal instruments. Distinct legal instruments are concerned:

- Formalisms. Distinct legal instruments are concerned:

- Representation in computer science. Knowledge representation: frame-based.

Situation: slots are partially filled (slotName := value). Alternatives result when empty slots are filled in.

Case: slots are completely filled (probably with the value «unknown»). - Customary law, machine law and statutory law

Situation. Situations have no language at all.

Situation: (i) the roles of actors; (ii) assumptions (hypothetical facts); (iii) rules which govern the situation; (iv) additional regulations which govern the situation.

Case: (i) claim; (ii) evidence; (iii) attacks; (iv) litigation can consist of several cases (e.g. criminal and civil).

Situation: deontic logic, abstract normative systems, etc.

Case: case modelling approaches, factors, etc.

Situation: customary law and machine law are in the foreground. As an example suppose a zebra crossing. Pedestrians aim to cross it. Statutory law (the road rules) regulates. However, ordinary people are governed primarily by customary law which superimposes. And finally the situation is governed by traffic lights – machine law steps in.

Cases: traditional hierarchies of legal sources prevail.

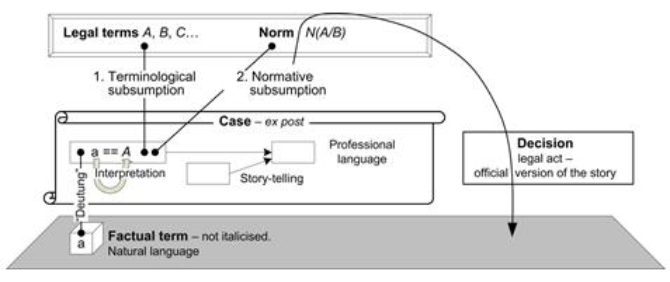

Cases appear on Is whereas legal rules appear on Ought (Fig. 3). Here we use a visualization pattern that is composed of two stages, the vertical Ought stage and the horizontal Is (Fig. 3). The two stages depict Kelsen’s categorical distinction between Is and Ought; see [Kelsen 1967, § 3 ff.].

| Attribute | Situation | Case |

| 1. Examples |

|

|

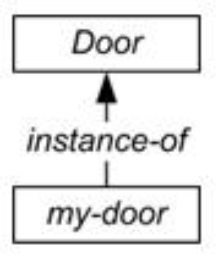

| 2. Type | Generic, i.e. a type, class. | Concrete, individual, an instance of class. |

| 3. Analysis | Ex-ante | Ex-post |

| 4. Time | Future | Past |

| 5. Alternatives | Possible | Not possible |

| 6. Language | Mental, non-textual, non-professional. | Textual, professional. Witnesses speak in non-professional language and jurists in professional. Visual representations, e.g. schemas, are supplementary |

| 7. Language elements | Roles. Legal status implicit in the roles | Roles: plaintiff, defendant, witness, expert. Argumentation |

| 8. Placing on Is and Ought | Is. In contrast, the type of a situation appears on Ought | Is. Subjective law. Legal proceedings are related to the objective law. |

| 9. Web example | www.help.gv.at | www.ris.bka.gv.at |

| 10. Legal instruments | Roles, assumptions, rules which govern the situation, additional regulations | Claim, evidence, attack |

| 11. Representation formalisms | Deontic logic worlds which can be accessed in the future | Facts in the past. Different narratives of the players |

| 12. Frame-based representation | Slots are partially filled | All slots are filled |

| 13. Customary vs. statutory law | Ordering: 1) machine law, 2) customary law, 3) statutory law | Traditional hierarchies of legal sources |

| 14. Bridging | Story-telling | |

Table 1: A comparison of structural elements of situation and case

2.1.

Distinguishing Conceptualisations for Situations and Cases ^

2.2.

Distinguished Elements in Situations and Cases ^

3.1.

A Notation for Situations ^

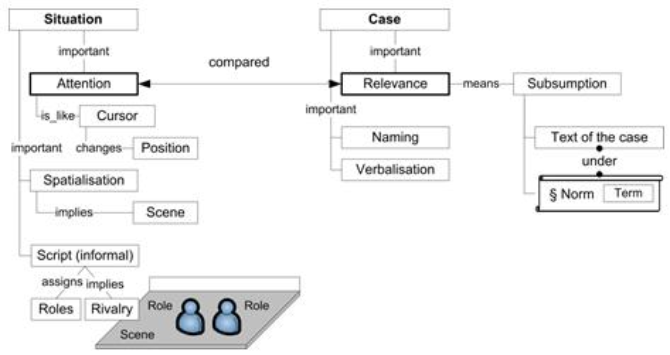

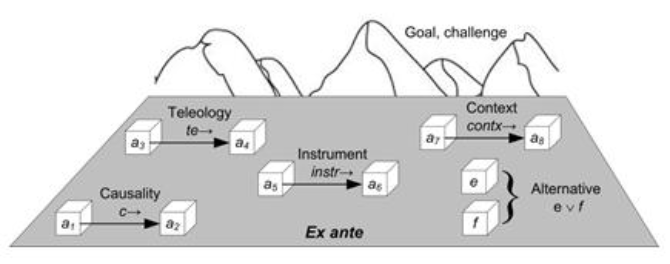

A situation appears on the horizontal Is stage and is described by the following entities (Fig. 5):

- Situative elements. These are constituents of the situation. They are denoted by small letters, e.g. a, b, c, driver, pedestrian, etc. They exist in time and space.

- Relations between the situative elements. There are many kinds of relations: causal (c→), teleological (te→), instrumental (instr→), context (contx→), etc. These relations are comprised by both legal relations such as debt, but also of empirical non legal relations. The relations represent different perspectives.

3.2.

A Notation for Case ^

The conceptualisation above is similar to the following form of inference (cf. the syllogism and also the modus ponens rule):

Minor premise: Socrates is a human

Major premise: Humans are mortal.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

3.3.

Modelling the Terminological Subsumption ^

4.

Conclusions ^

5.

Acknowledgement ^

V. Čyras has been supported by the project «Theoretical and engineering aspects of e-service technology development and application in high-performance computing platforms» (No. VP1-3.1-ŠMM-08-K-01-010) funded by the European Social Fund.

6.

References ^

Bex, Floris J.; van Koppen, Peter J.; Prakken, Henry; Verheij, Bart, A hybrid formal theory of arguments, stories and criminal evidence. Artificial Intelligence and Law 18(2):123–152 (2010).

Bex, Floris; Bench-Capon, Trevor; Atkinson, Katie, Did he jump or was he pushed? Abductive practical reasoning. Artificial Intelligence and Law 17(2):79–99 (2009).

Kelsen, Hans, Pure Theory of Law. 2nd ed., Max Knight, trans. University of California Press, Berkeley, 1967.

Prakken, Henry; Sergot, Marek, Contrary-to-duty obligations. Studia Logica 57(1):91–115 (1996).

Sartor, Giovanni, Legal Reasoning: A Cognitive Approach to the Law. A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence, vol. 5. Springer, Heidelberg (2007).

Tosatto, Silvano Colombo; Boella, Guido; van der Torre, Leendert; Villata, Serena, Visualising normative systems: an abstract approach. In: T. Ågotnes, J. Broersen, D. Elgesem (Eds.): Deontic Logic in Computer Science – 11th International Conference, DEON 2012, Bergen, Norway, July 16-18, 2012, Proceedings. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 7393, pp. 16–30. Springer (2012).

Vytautas Čyras, Docent, Vilnius University.

Friedrich Lachmayer, Professor, University of Innsbruck.

- 1 An aircraft system that operates independently of ground-based equipment and air traffic control in warning pilots of the presence of other aircraft that may present a threat of collision. If the risk of collision is imminent, the system indicates a manoeuvre that will reduce the risk of collision; see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airborne_Collision_Avoidance_System last accessed 28.1.2013.