1.

Introduction ^

2.

Preparing the Battle Ground ^

3.

Let The Battle Commence ^

3.1.

All is Fair in Law and War ^

At the turn of the 13th century however, trial by jury had largely replaced trial by combat – if not the duel between individuals, then at least the larger wager of battle. One of the last large judicial wagers of war took place 1396 in Scotland, in the «battle of the clans» in Perth. Considerable uncertainty surrounds this event, its historicity however is confirmed from a bill to the exchequer accounts that had an entry which states «For timber, iron, and making of a battlefield for 60 persons fighting on the inch at Perth, £14:25 or 14 pounds 2 shillings.» Access to justice, even then, came at a price, though the true costs would only become apparent after the trial was over. Here we will tell but one version of the story.27 The dispute itself was a side issue in the 350 year feud over territory and cattle between the Chattan confederation on one side – an unusual, semi-permanent alliance of Scottish clans including the Clans Macpherson and Davidson – and Clan Cameron on the other.

- «The trumpets of the King sounded a charge, the bagpipes blew up their screaming and maddening notes, and the combatants, starting forward in regular order, and increasing their pace, till they came to a smart run, met together in the centre of the ground, as a furious land torrent encounters an advancing tide.

- Blood flowed fast, and the groans of those who fell began to mingle with the cries of those who fought. The wild notes of the pipes were still heard above the tumult and stimulated to further exertion the fury of the combatants.

- At once, however, as if by mutual agreement, the instruments sounded a retreat. The two parties disengaged themselves from each other to take breath for a few minutes. About twenty of both sides lay on the field, dead or dying; arms and legs lopped off, heads cleft to the chin, slashes deep through the shoulder to the breast, showed at once the fury of the combat, the ghastly character of the weapons used, and the fatal strength of the arms which wielded them.»

Lord Ellenborough:

- «The discussion which has taken place here, and the consideration which has been given to the facts alleged, most conclusively show that this is not a case that can admit of no denial or proof to the contrary; under these circumstances, however obnoxious I am myself to the trial by battle, it is the mode of trial which we, in our judicial character, are bound to award. We are delivering the law as it is, and not as we wish it to be, and therefore we must pronounce our judgment, that the battle must take place.»36

Parliament abolished wager of battle shortly after. While this should have been the end of the story of trial by combat, this underestimates the ingenuity of the British citizen. In December 2002, a 60-year-old mechanic challenged the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency over a £25 fine. He claimed a right to a trial by combat under the old law, arguing that its repeal was not constitutional. The DLVA was asked to nominate a «champion», the fight would be to the death, using «samurai swords, Ghurka knives or heavy hammers». This claim was however denied by a court of magistrates in Bury St Edmunds, and he was further fined39

4.

Battle Joined ^

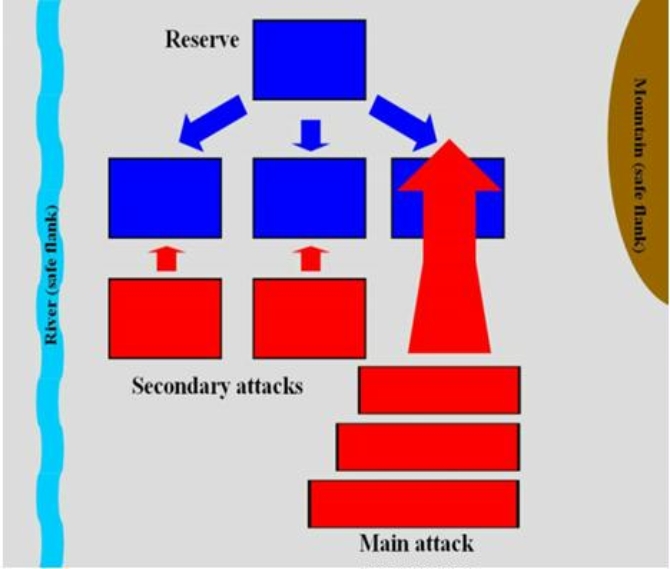

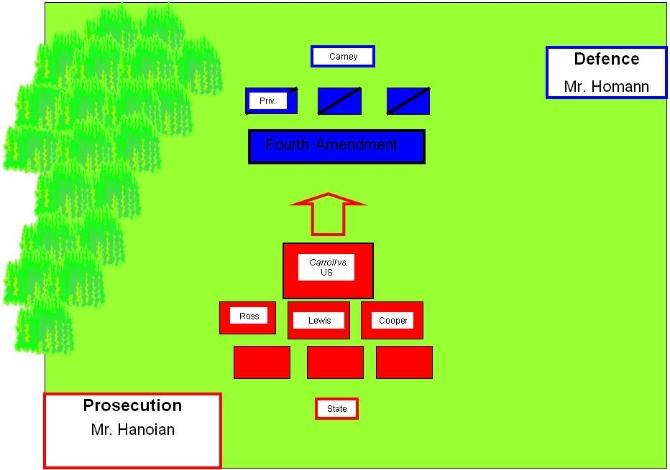

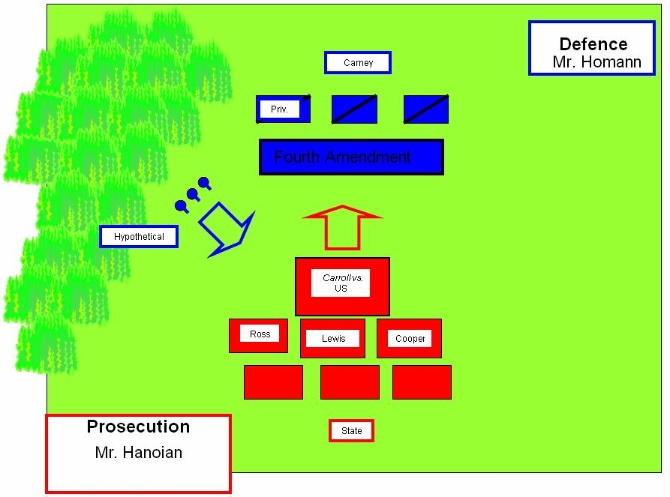

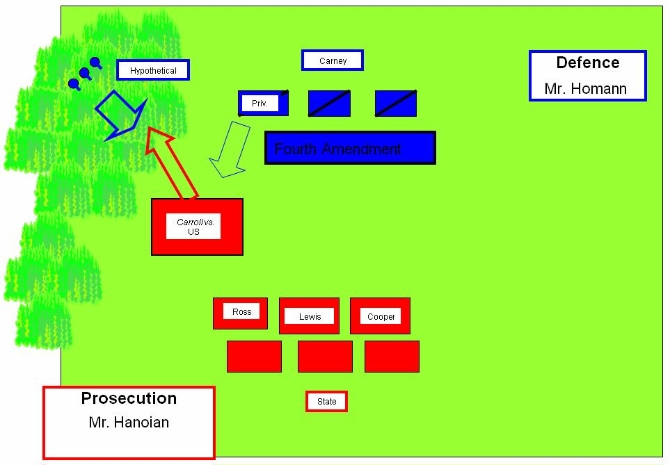

Figure 1: Explanation of «attack in oblique order»41

5.

Literatur ^

Anon, The history of the feuds and conflicts among the clans in the northern parts of Scotland and in the Western Isles; from the year M.XXXI. unto M.DC.XIX. To which is added, A collection of curious songs in the Gallic language, published from an original manuscript, 1780

Ashley, K., «Teaching a process model of legal argument with hypotheticals». Artificial Intelligence and Law, 17, pp. 321–370, 2009

Ashley, K., Desai, R. and Levine, J.M., «Teaching case-based argumentation concepts using dialectic arguments vs. didactic explanations», in S.A. Cerri, G. Gouardères and F. Paraguaçu (eds.), Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Intelligent Tutoring Systems, ITS 2002, Springer: Berlin 2002, pp. 585–595

Atiyah, P.S. and Summers, R.S., Form and Substance in Anglo-American Law: A Comparative Study in Legal Reasoning, Legal Theory and Legal Institutions, Oxford University Press: New York 1987

Barnes, T. G., Shaping the common law: from Glanvill to Hale, Stanford University Press: Stanford 2008, pp. 1188–1688

Cáceres, E., Psicología y Constructivismo Jurídico, in M. Muñoz de Alba (ed.), Violencia Social, UNAM: Mexico City 2002, pp. 335–342

Cox, R., «Representation construction, externalised cognition and individual differences». Learning and Instruction, 9, 2009, pp. 343–363

Danzig, R., A Comment on the Jurisprudence of the Uniform Commercial Code, 27 Stan. L. Rev., 1975, p. 621

Duxbury, N., The Nature and Authority of Precedents, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge

Dyer, G., Ivanhoe, Chivalry, and the Murder of Mary Ashford , Criticism 39.3, 1997, pp 383–408

Fitz Gerald, W., The duel between two of the O’Connors of Offaly in Dublin Castle on the 12th. Sept., 1583. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Ser. 5, Vol. XX, 1910, pp. 1–5

Garcia Maynez, E., 2000. Introduccion al Estudio del Derecho, Porrua: Mexico City 2008

Grise, J. E., Gelter, M. and Whitman, R., Rudolf von Jhering’s influence on Karl Llewellyn, Tulsa L. Rev. 48, 2012, pp. 93–143

Hall, J., Trial of Abraham Thornton, William Hodge & Co: Edinburgh and London 1926

Jhering, R.v., The Struggle for Law, trans Lalor, J. J., Lawbook Exchange: Union, NJ 1919

Kritzer, H. M., Lawyer fees and lawyer behavior in litigation: What does the empirical literature really say. Tex. L. Rev. 80, 2001, p. 1943

Larkin, J.H. and Simon, H.A. 1987. «Why a diagram is (sometimes) worth ten thousand words». Cognitive Science, 11, pp. 65–100

Legrand, P., «How to compare now». Legal Studies, 16, 1996, pp. 232–42

Legrand, P. and Machado, A., Are civilians educable? Legal Studies, 18, 1998, pp. 216–30

Llewellyn K. N., The bramble bush, Oceana: New York 1930

Llewellyn K. N., Remarks on the Theory of Appellate Decision and the Rules or Canons about how Statutes are to be Construed, 3 VAND. L. REV., 1950, p. 395

MacCormick, D.N. and Summers, R., Interpreting Precedents: A Comparative Study, Ashgate: Dartmouth 1997

MacQueen, H., Desuetude, the cessante mazim and trial by combat in Scots law Journal of Legal History, 1986, pp. 90–97

Mackintosh Shaw, A., The clan battle of Perth in 1396: An episode of Highland history: With an enquiry into its causes, and an attempt to identify the clans engaged in it, W.P. Griffith: London 1874

Megarry, R. E., & Garner, B. A. (eds.). A new miscellany at law: Yet another diversion for lawyers and others, Hart Publishing: London 2005

Moorhead, R., Conditional fee agreements, legal aid and access to justice, U. Brit. Colum. L. Rev. 33, 1999, p. 471

Neilson, G., Trial by Combat, William Hodge & Co. Glasgow 1890

Re, E. D., The Roman Contribution to the Common Law, Loy. L. Rev. 39, 1993, p.295

Schafer, B., Crowdsourcing and cloudsourcing CCTV surveillance, Datenschutz und Datensicherheit-DuD 7, 2013, p. 434–439

Scott W. R., St. Valentine’s Day; or, The Fair Maid of Perth (Chronicles of the Canongate, Second Series), Cadell and Co.: Edinburgh 1828

Shoenfeld, M., «Waging battle: Ashford vs. Thornton, Ivanhoe and legal violence», in Simmons, Clare, Medievalism and the Quest for the «Real» Middle Ages, London, Routledge, 1997, pp. 61–86

Stuckey, R., Best Practices for Legal Education, CLEA: New York 2007

Sinclair, M., Only a Sith Thinks Like That : Llewellyn’s' Dueling Canons,’Eight to Twelve, New York Law School Law Review, 52, 2006, p. 919 ff.

Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, Dirección General de la Coordinación de Compilación y Sistematización de Tesis, Libro Blanco de la Reforma Judicial: Una agenda para la justicia en México (Mexico City: Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación), 2006

Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, Estudio sobre la reforma judicial integral. Diagnóstico ciudadano y conclusiones de los foros. Problemario: Problema 19 (Mexico City: Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación) 2008

Thayer, J.B., «The Older Modes of Trial, 5 Harv. Law Rev. 45, 1891, p. 65

Teubner, G., How the law thinks: toward a constructivist epistemology of law, Law & Society Review, 23, 1989, pp. 727–758

Twining W., Karl Llewellyn and the Realist Movement, Weidenfeld and Nicolson: London 1973

Vogel, T., Fehderecht und Fehdepraxis im Spätmittelalter am Beispiel der Reichshauptstadt Nürnberg, Lang: Frankfurt/M. 1998

Voyatzis P., Schafer B., The Battle of the Precedents: Reforming Legal Education in Mexico Using Computer-Assisted Visualisation in Zenon Bankowski, Paul Maharg, Maks Del Mar (eds.), The Arts and the Legal Academy Beyond Text in Legal Education Farnham, Ashgate, 2013, pp. 149–168

Whitman, J., Commercial Law and the American Volk: A Note on Llewellyn’s German Sources for the Uniform Commercial Code. Yale Law Journal 97.1, 1987, pp. 156–175

Burkhard Schafer, Professor for Computational Legal Theory, SCRIPT Centre, School of Law, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9YL UK.

Panagia Voyatzis, Research Student, School of Law, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9YL UK.

- 1 Emiliano Zapata, Mexican revolutionary and self-taught lawyer.

- 2 Der Kampf um das Recht. Vortrag des Hofrates Professor Jhering, Gehalten in der Wiener Juristischen Gesellschaft am 11. März 1872 notes from a stenograph available at http://www.koeblergerhard.de/Fontes/JheringDerKampfumsRecht.htm. The English Translation of the published version, «The struggle for law» omits the reference to legal education.

- 3 Jhering 1919.

- 4 Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación. 2006 p. 166.

- 5 Ibid, pp. 166–168.

- 6 Suprema Corte de Justicia de la Nación, 2006 p. 168.

- 7 Corte de Justicia de la Nación, Libro Blanco de la Reforma Judicial, pp. 166–169.

- 8 Senado de la República, 2007.

- 9 Atiyah and Summers 1987 pp. 115–116.

- 10 MacCormick and Summers 1997, p. 544.

- 11 Cáceres 2002.

- 12 Duxbury 2008 p. 23.

- 13 Garcia Maynez 2000: pp. 68–75.

- 14 Llewellyn, 1950; see also Sinclair 2006.

- 15 Llewellyn 1930 p. 6.

- 16 Twinig 1973 p. 91ff.

- 17 Grise, Gelter, and Whitman 2012.

- 18 See e.g. Whitman 1987.

- 19 For a typical criticism see Danzig (1975).

- 20 Frank 1950.

- 21 MacQueen 1986.

- 22 Thayer, 1891.

- 23 Barnes, 2008.

- 24 See e.g. Re, 1993.

- 25 Neilson 1890 pp. 46–51.

- 26 See e.g. Moorhead, 1999; Kritzer 2001.

- 27 For a fuller account, see http://unknownscottishhistory.com/pdf/TheBattle of the North Inch.pdf ; dated, but still an important source is Shaw 1874.

- 28 The ideal of public trial is of course another traditional feature of common law litigation, and indeed another of the changes Mexico is introducing. As William Blackstone, the great English law commentator, would write in 1789: This open examination of witnesses viva voce, IN THE PRESENCE OF ALL MANKIND, is much more conducive to the clearing up of truth, than the private and secret examination taken down in writing before an officer, or his clerk, in the ecclesiastical courts, and all others that have borrowed their practice from the civil law. William Blackstone, Commentaries, 3: pp. 349–67, 370–81, 383–85.

- 29 Walter Scott, St. Valentine’s Day; or, The Fair Maid of Perth (Chronicles of the Canongate, Second Series) Edinburgh: Printed for Cadell and Co., Edinburgh; 1828. Chapter 34.

- 30 Anon, 1780.

- 31 Fitz Gerald 1910.

- 32 Megarry and Garner 2005, p. 62.

- 33 Shoenfeld 1997 p. 61.

- 34 Schafer 2013.

- 35 Ashford vs. Thornton (1818) 106 ER 149.

- 36 Hall 1926 p. 179.

- 37 Ibid at p. 175.

- 38 Dyer 1997.

- 39 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1416262/Court-refuses-trial-by-combat.html.

- 40 See e.g. Vogel 1998.

- 41 From http://www.theartofbattle.com/, with kind permission. This website has excellent animated battle maps, the reader can get a very good idea of how our ultimate ambition is, though so far their skills surpass ours.

- 42 See e.g. Ashley 2009, Ashley at al 2002.

- 43 Voyatzis and Schafer 2013.

- 44 Stuckey 2007 p.214.

- 45 Ashley 2009.