1.

Introduction ^

The aim of the CEPEJ of the Council of Europe is the improvement of the efficiency and functioning of justice in the member states, and the development of the implementation of the instruments adopted by the Council of Europe to this end.

2.

Aim and Objectives of CEPEJ ^

The CEPEJ was established on 18 September 2002 with Resolution Res(2002)12 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe.

The creation of the CEPEJ demonstrates the will of the Council of Europe to promote the rule of law and fundamental rights in Europe, on the basis of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and especially its Articles 5 (Right to liberty and security), 6 (Right to a fair trial), 13 (Right to an effective remedy), 14 (Prohibition of discrimination). Driven by the substantial number of cases at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) dealing with overly long proceedings in front of courts in European states, the Council of Europe has initiated a reflection on efficiency of justice and adopted Recommendations which contain ways to ensure both its fairness and efficiency.

- to analyse the results of the judicial systems;

- to identify their difficulties;

- to define concrete ways to improve the evaluation of their results and functioning;

- to provide assistance at request; and

- to propose to the competent instances of the Council of Europe the fields where it would be desirable to elaborate a new legal instrument.

In the Action Plan adopted at their 3rd Summit (Warsaw, 16–17 May 2005), the heads of state and governments decided to develop the evaluation and assistance functions of CEPEJ in order to help member states to deliver justice fairly and rapidly. They also invited the Council of Europe to strengthen cooperation with the European Union in the legal field, including cooperation with the CEPEJ.

3.

Evaluation of Judicial Systems ^

4.

Aim of the Report ^

- to provide a public policy tool for policy makers, legal professionals and researchers that will assist them in conducting judicial reforms;

- to give a detailed picture of the situation of the European judicial systems. Comparative tables, figures and the comments help to understand the day-to-day functioning of courts, underline the main trends in judicial systems and identify any problems with a view to improving the quality, fairness and efficiency of the public service of justices;

- to provide a sound tool for enhancing mutual knowledge of judicial systems and strengthening mutual confidence between legal professionals; and

- to define a set of key quantitative and qualitative data to be regularly collected and equally processed in all member states, bringing out shared indicators of the quality and efficiency of court activities in the Council of Europe member states and highlighting organizational reforms, practices and innovations, which enable improvement of the service provided to court users.

It is no surprise, therefore, that the CEPEJ evaluation exercises have shown since 2004 with factual data that ICT is playing a growing role within the justice administration and the justice service provision. Examples range from the support of case and file management, to the use by judges of templates to support the formulation of judicial decisions, on-line access to law and jurisprudence databases, availability of web services, use of electronic filing, and exchange of electronic legal documents. ICT can be used to enhance efficiency, but also «to facilitate the user’s access to the courts and to reinforce the safeguards laid down in Article 6 ECHR: access to justice, impartiality, independence of the judge, fairness and reasonable duration of proceedings».3

6.

Comments per countries in particular ^

Spain: courts are implementing electronic submission of claims. With its strategic plan for modernising the justice system 2009–2012, Spain is developing a secure document exchange system (Lexnet) that facilitates communications between the courts and several legal actors (prosecutors, solicitors, court clerks, etc.). Approx. 22000 users currently access it. Furthermore, a judicial interoperability platform (EJIS) has been set up to allow court networking and real time data exchange on particular matters or persons. The implementation of both facilities is part of a new system, whose aim is to achieve a flexible and efficient justice system.

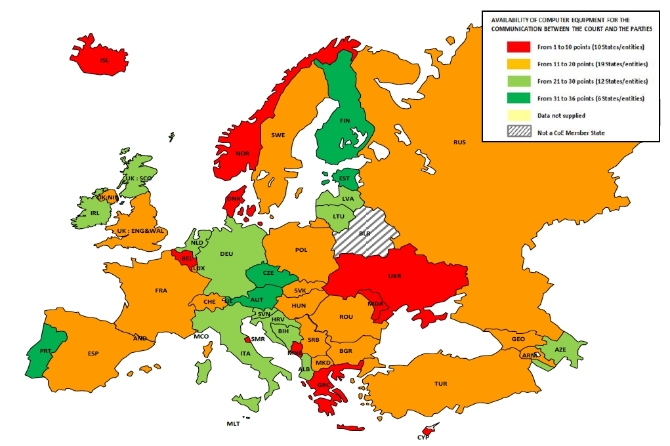

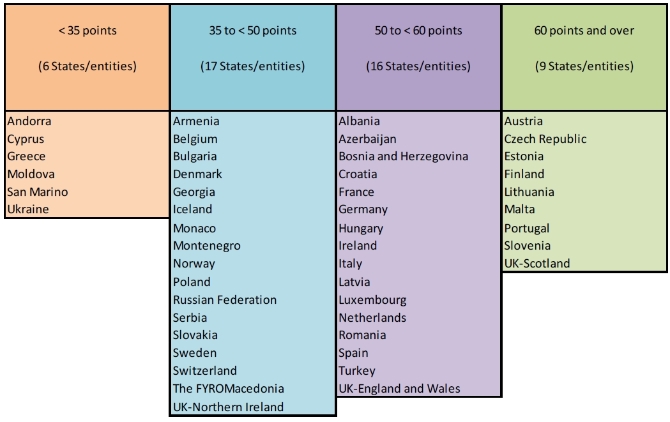

Nevertheless, the trend is encouraging. A good level of computer facilities for communication can also be found in one third of the states or entities. However, it must be kept in mind that this indicator does not assess the performance of such systems. Austria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Malta, Portugal7 have particularly high scores. Italy is now finally succeeding in deploying its on-line trial infrastructure8 and in France the e-Barreau system9 that allows data and document exchange between lawyers and courts, is now operative.

6.1.

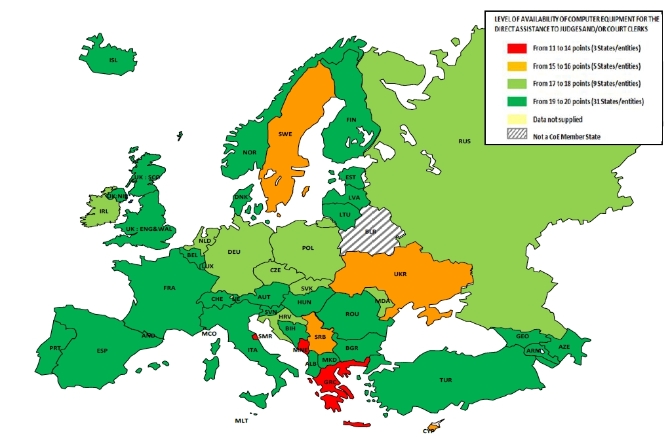

Level of computerisation of courts for the three areas of application ^

6.2.

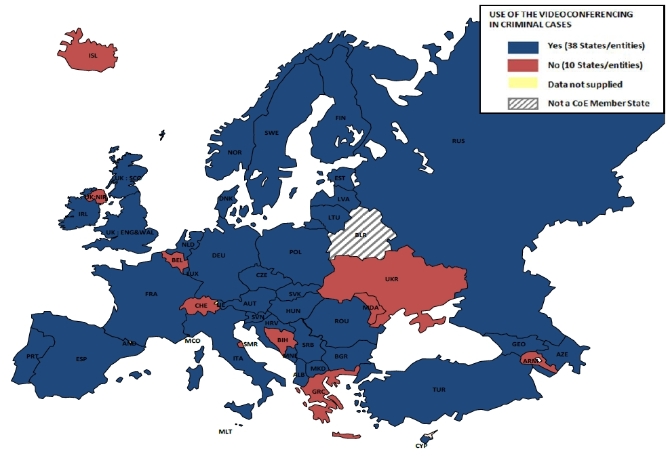

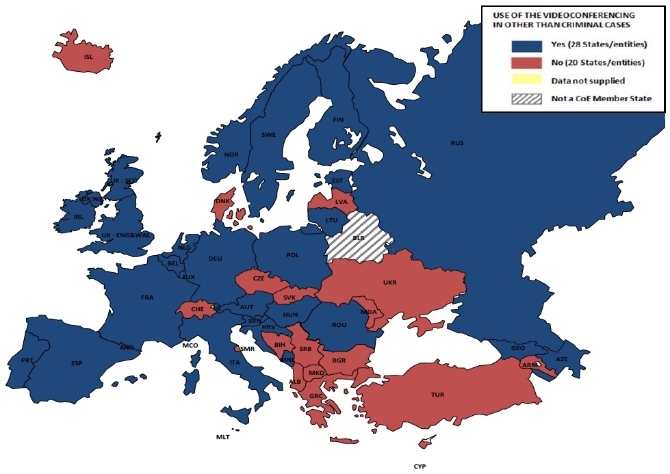

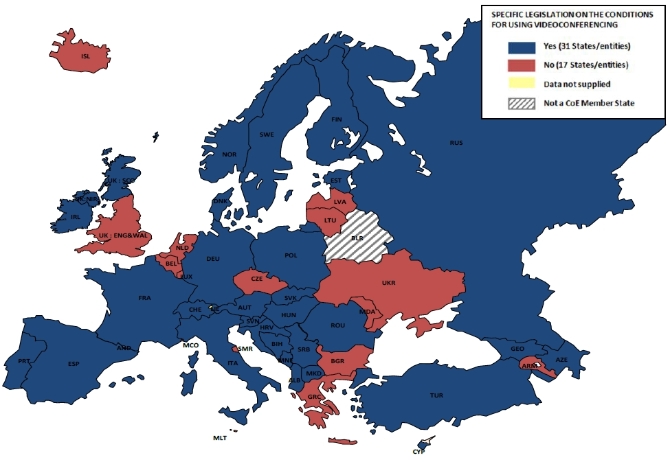

Use of videoconferencing ^

6.3.

Comments per countries in particular ^

In almost 80% of the states or legal entities, video-conferencing is used in criminal cases. The video- conference technology offers judges and prosecutors the possibility to question people summoned to a court that is nearest to their domicile and equipped with a video-conference system (Austria) or accused/convicted persons who are in custody and benefit from specially equipped rooms in detention (France, Italy, Netherlands12 for specific cases). Child victims and witnesses of violent crime are increasingly questioned in specially equipped questioning rooms (Azerbaijan, Germany). In other cases, questioning of undercover investigators can be carried out in a secret location in criminal proceedings by disguising the voice and face (Azerbaijan, Germany) or police officers may present evidence from their police station (UK-England and Wales).

7.

Overall impact ^

8.

ENCJ Guidelines ^

- Digital access to justice is becoming an integral part of access to justice as fundamental right, and its expansion should be a top priority for the judiciaries.

- It is an inevitable trend to digitally record court hearings in order to secure the evidence and to make that evidence available, for instance, in appeal; courts should implement such systems as soon as feasible.

- Most budget systems of judiciaries cannot easily accommodate the levels of capital investment IT-applications such as digital recording require; this issue should be specifically addressed. Cost benefit analysis is needed to underpin investment decisions.

- Judiciaries should learn from on-line dispute resolution mechanisms and applications that are currently available on the internet.15

Georg Stawa, Leiter der Abteilung für Projekte, Strategie und Innovation in der Präsidialsektion im Bundesministerium für Justiz und Vizepräsident der Europäischen Kommission für die Effizienz der Justiz des Europarates (CEPEJ).

- 1 For a comprehensive list of relevant CEPEJ» documents is available at http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/cooperation/cepej/textes/default_en.asp.

- 2 Detailed information is described in: Velicogna M. (2007), Use of Information and Communication technology in European Judicial systems, CEPEJ Study N° 7 (Strasbourg).

- 3 Consultative Council of European Judges (CCJE), Opinion No.(2011)14 «Justice and information technologies (IT)» adopted by the CCJE at its 12th plenary meeting (Strasbourg, 7–9 November 2011).

- 4 On the subject see: Contini, F. and Lanzara, G.F. (eds) ICT and Innovation in the Public Sector – European Studies in the Making of E-Government, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- 5 CCJE Opinion No.(2011)14 «Justice and information technologies (IT)» – see above.

- 6 For a more detailed analysis of the Slovenian case see: Strojin, G. «COVL: Central Department for Enforcement on the basis of Authentic Document of the Slovenian Judiciary» Building Interoperability for European Civil Proceedings Online, Bologna, 15–16 June 2012.

- 7 For an analysis of the Portuguese case see: Gomes, C., Fernandes, D., Fernando, P. «Citius – Payment Order Procedure», Building Interoperability for European Civil Proceedings Online, Bologna, 15–16 June 2012, http://www.irsig.cnr.it/BIEPCO/documents/case_studies/biecpo_final.pdf.

- 8 Carnevali, D., Andrea Resca, A., «The Civil Trial On-Line (TOL): A True Experience of e-Justice in Italy» , Building Interoperability for European Civil Proceedings Online, Bologna, 15–16 June 2012, http://www.irsig.cnr.it/BIEPCO/documents/case_studies/TOL%20System_Report_Italy_28mag12%20.pdf.

- 9 For an analysis of the complexity of developing e-Barreau see: Velicogna, M., Errera A.; Derlange, S., «e-Justice in France: the e-Barreau experience», Utrecht Law Review, Volume 7, Issue 1 (January) 2011, pp. 163–187, http://ssrn.com/abstract=1763270.

- 10 Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey.

- 11 For more information see: http://www.e-codex.eu/.

- 12 For an analysis of the situation in the Netherlands see: Ng, G.Y., & F. Henning. «The Challenge of Collaboration – ICT implementation networks in courts in the Netherlands.» TRASTransylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, no. 28 (2009): 27–44.

- 13 http://www.encj.eu/.

- 14 http://www.encj.eu/images/stories/pdf/workinggroups/encj_report_judicial_reform_ii_approved.pdf.

- 15 I.e. like www.modria.org.