1.

Introduction ^

2.

Court IT, Opinion 14 and Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights ^

First of all, it is important to note that the CCJE welcomes IT as a means to improve the administration of justice, for its contribution to the improvement of access to justice, case-management and the evaluation of the justice system and for its central role in providing information to judges, lawyers and other stakeholders in the justice system as well as to the public and the media. The Opinion’s main normative framework is Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR). This article provides for access to courts, impartiality and independence of the judge, fairness and reasonable duration of proceedings to everyone. The normative framework also includes earlier CCJE Opinions and the Magna Charta of Judges, adopted in November 2010.2

3.

How far have the courts in Europe come with IT? ^

- In the highest scoring group, technology for direct support and court management is in place in all courts, and interaction technology is used to communicate externally. There are 9 countries in this group: Austria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Lithuania, Malta, Portugal, Slovenia and UK-Scotland.

- The second group has mostly implemented direct support and court management technology, but its use of external communication technology is still limited. There are 16 countries in this group: Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Romania, Spain, Turkey, and UK-England and Wales.

- The third group includes 17 member states: Armenia, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Georgia, Iceland, Monaco, Montenegro, Norway, Poland, Russian Federation, Serbia, Slovakia, Sweden, Switzerland, The FyroMacedonia and UK-Northern Ireland.

- The last group includes Andorra, Cyprus, Greece, Moldova, San Marino and Ukraine.

4.

The role of IT in administering justice ^

5.

Access to justice ^

In Opinion 14, the CCJE states that full, accurate and up to date information about procedure is a fundamental aspect of the guarantee of access to justice identified in Article 6 of the Convention (ECHR). This should generally include details or requirements necessary to invoke jurisdiction, and information on the operation of the judicial system. Case law, at least landmark decisions, should be made available on in the internet free of charge, in an easily accessible form, and taking account of personal data protection. CCJE welcomes the use of international case-law identifiers like the European Union Case Law Identifier (ECLI) to improve access to foreign case law.6

5.1.

Opportunities ^

Communication technology offers opportunities for such increasingly complex levels of interaction. A much used benchmark was developed by the European Union (EU) for electronic interaction between citizens and government services:

Stage 1: Information online about public services

Stage 2: one-way interaction: downloading of forms

Stage 3: two-way interaction: processing of forms (including authentication), e-filing

Stage 4: Transaction: case handling, decision and delivery (payment).

5.2.

Access to legal information ^

5.3.

Access to courts ^

According to the CCJE survey, courts and court systems increasingly have their own web sites. Less than half of those who responded say all or most courts have their own web sites. Some have portals, a few say they have one site for all courts; a few others have sites only for the Supreme Court. The websites provide general information on the judiciary, the court, its organisation, information for court users and for the media, forms to submit to the courts, and case law.

| Facility in all courts | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 |

| Electronic web forms | 13 | 11 | 15 | 21 |

| Special web sites | 18 | 14 | 20 | 40 |

| Other electronic communication | 12 | 15 | 16 | 21 |

| Source: CEPEJ 2006, p. 69, 2008 p. 86, 2010 p. 93, 2012 p. 111 | ||||

Table 1: Electronic communication in courts in Europe

| Facility in all courts | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 |

| Electronic database of jurisprudence | 33 | 33 | 41 | 42 |

| Source: CEPEJ 2006, p. 69, 2008 p. 86, 2010 p. 93, 2012 p. 111 | ||||

Table 2: Electronic jurisprudence databases in courts in Europe

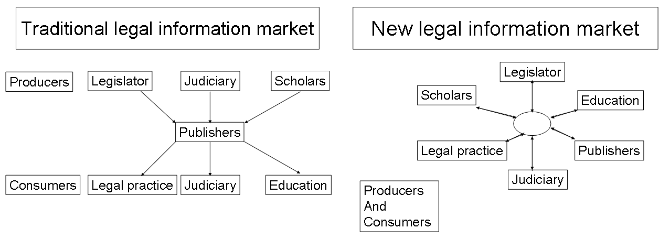

These databases may be collections for the use of single courts, for the court system as a whole, or open to the general public. Where courts start to publish their own decisions, the market for legal information changes fundamentally. Traditionally, case law and jurisprudence are provided to publishers by the producers, judiciaries, lawyers or scholars. The publishers then provide them to the consumers, mainly the judiciaries, legal practitioners and educational institutions.

5.4.

E-filing ^

6.

IT in the court procedure ^

6.1.

Implementation ^

6.2.

Office technology ^

| Facility in all courts | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 |

| Word processing | 40 | 42 | 45 | 45 |

| 31 | 33 | 41 | 45 | |

| Internet connections | 33 | 33 | 40 | 45 |

| electronic jurisprudence databases | 33 | 33 | 41 | 42 |

| electronic files | 20 | 18 | 21 | 25 |

| Source: CEPEJ 2006, p. 69, 2008 p. 86, 2010 p. 93, 2012 p. 111 | ||||

Table 3: Technology on the judge’s desk in courts in Europe

6.3.

Case law or jurisprudence databases ^

Jurisprudence databases deserve some special attention because the functionality and capabilities behind them can be very diverse.11 A jurisprudence collection is a repository of interesting or innovative decisions for the purpose of developing the law and its application for lawyers. Decisions are supplied on an ad hoc basis. Not every decision goes into the repository. Some infrastructure is needed, but it can be similar to producing the paper version. The purpose of a jurisprudence collection is to present innovative or landmark decisions to aid the development of the rule of law. The process involved can be separate from the regular court process of case disposition. A very different matter is a collection of all decisions in an electronic archive. All decisions need to go in. There is a process in place to ensure they do. This process is part of the regular business process of the court. In both models, decisions can be published or not. The purpose of publication is also public scrutiny and transparency of the courts.

6.4.

Knowledge management ^

| content | state sourced only | privately sourced only | both |

| national legislation | 18 | 7 | 8 |

| European legislation | 8 | 2 | 8 |

| national case law | 9 | 5 | 9 |

| international case law | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| law eeview articles | 4 | – | 4 |

| Source: CCJE survey on the use of IT in courts | |||

Table 4: Sources of legal information databases in courts in Europe

6.5.

Court management and administration ^

| Facility in all courts | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | 2010 |

| Case registration | 25 | 26 | 34 | 40 |

| Court/case management | 17 | 20 | 25 | 27 |

| Financial management | 23 | 26 | 31 | 32 |

| Source: CEPEJ 2006, p. 69, 2008 p. 86, 2010 p. 93, 2012 p. 111 | ||||

Table 5: Court management technology in courts in Europe XE «Function Information Technology in Courts in Europe»

6.6.

Tools for the hearing ^

7.

IT-governance and judicial independence ^

8.

Critical analysis ^

8.1.

What is prominent? ^

8.2.

What are the concerns? ^

In my earlier work, I concluded that the most salient deficiency in developing court IT is that of strategy: a strategic vision of the processes involved in administering justice, shaped by knowledge and understanding of the role of information in courts. In order for IT innovations in the court processes to actually improve court processes and not detract from them, the judiciary’s leadership and the IT function both need to understand how information works in the courts and the implications for IT. From the above, I think the conclusion is justified that judiciaries need to have sufficient control over their own IT, which may also require changes in the governance structure. In some cases, changes in the governance structure may be needed to support strategy and policy formation and to support prioritizing funding and budgeting in accordance with the policies.15

8.3.

Other issues ^

In my opinion, the judiciaries of Europe could benefit from more cooperation and exchanges between member countries with regard to IT. Court systems can learn from each other’s experience with IT, precisely because IT is an evolving phenomenon. The results of experimentation are important for innovation. I have long advocated institutionalizing experimentation which can translate the needs of administering justice into IT applications. For example: the requirements for electronic filing are so different, one wonders whether an exchange of experiences on the requirements for e-filing might help its introduction.

9.

In conclusion ^

10.

References ^

CCJE Magna Charta of Judges. Consultative Council of European Judges, on www.coe.int/ccje.

CCJE Opinion 14, Consultative Council of European Judges, Justice and Information Technologies, Opinion 14, on www.coe.int/ccje.

CEPEJ 2006. European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, European Judicial Systems Edition 2006 (2004 data). www.coe.int/cepej.

CEPEJ 2008. European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, European Judicial Systems Edition 2008 (2006 data). www.coe.int/cepej.

CEPEJ 2010. European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice, European Judicial Systems Edition 2010 (2008 data). www.coe.int/cepej.

European Union. Benchmarking e-government projects.

Reiling 2006. «Doing justice with information technology.» Information & Communications Technology Law 15 (2006): 189–200.

Reiling 2009. Technology for Justice, How Information Technology can Support Judicial Reform, Law, Governance and Technology Series, Leiden University Press, Leiden, 2009. free e-book download on www.doryreiling.com.

Reiling 2010. IT and the Access to Justice Crisis, Voxpopulii, blog for the Cornell University Law School Legal Information Institute, August 1, 2010. http://blog.law.cornell.edu/voxpop/2010/08/01/it-and-the-access-to-justice-crisis/.

Reiling 2011. Understanding IT for Dispute Resolution, International Journal for Court Administration, April 2011.http://www.iaca.ws/files/UnderstandingITforDisputeResolution-DoryReiling.pdf.

Reiling 2012. Information Technology in Courts in Europe, International Journal for Court Administration, June 2012.http://www.iaca.ws/files//journal-eighth_edition/reiling-technology_in_courts_in_europe.pdf.

Susskind Richard. 1998. The Future of Law. Oxford University Press.

Dory Reiling, mag. iur. Ph.D., is a judge in the first instance court in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She was the first information manager for The Netherlands» Judiciary, and a senior judicial reform expert at The World Bank. She was a member of the Justice and IT-subcommission of the Legal Commission of the Council of Europe, and chair of the subcommission’s working group on digital signatures. She is currently on the editorial board of Computerrecht, the The Hague Journal on the Rule of Law, and the Springer Law, Governance and Technology Series. She chairs the Netherlands Judiciary’s knowledge systems user advisory board and is involved in digitalizing court procedures in the Netherlands. She has a weblog in Dutch and an occasional weblog in English, and can be followed on Twitter at @doryontour.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the International Journal for Court Administration, June 2012.

- 1 http://www.coe.int/t/dghl/cooperation/ccje/textes/Avis_en.asp; All websites were last visited on October 6, 2013.

- 2 Magna Charta of Judges, adopted by CCJE in November 2010, available on the CCJE website at www.coe.int/ccje. The spelling Charta is original.

- 3 The survey methodologies do not enable drawing inferences with great precision.

- 4 CEPEJ 2006, 2008, 2010, 2012, www.coe.int/cepej.

- 5 Reiling 2009 part 4.

- 6 A new case identification/neutral citation system, a result of the recent Council of the European Union decision, designed to facilitate cross-border access to national case law (whether from courts or tribunals). Council conclusions inviting the introduction of the European Case Law Identifier (ECLI) and a minimum set of uniform metadata for case law Official Journal C 127, 29/04/2011 P. 0001 – 0007.

- 7 Reiling 2010.

- 8 I thank my colleague Marc van Opijnen for this chart.

- 9 CEPEJ 2012 p. 111.

- 10 ECHR October 5 2006, Marcello Viola c. Italy, no. 45106/04 ; ECHR October 27 2007, Asciutto c. Italy, no. 35795/02.

- 11 Reiling 2009 p. 52–53.

- 12 Reiling 2009 part 3.

- 13 Reiling 2009 part 5.

- 14 CEPEJ 2010 p. 291, www.coe.int/cepej.

- 15 Reiling 2009 part 2.