1.

The Challenge ^

2.

Responding to the Challenge ^

2.1.

Merging Simulation and Visualization in Contract Education ^

2.2.

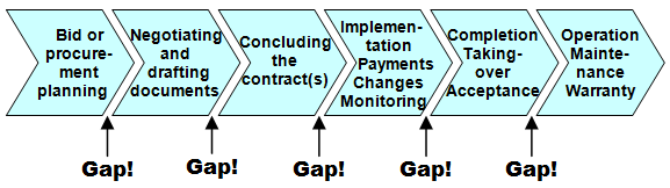

Example: Using Visualization to Bridge the Gaps in the Contracting Process ^

2.3.

Gamification in Contract Education ^

2.4.

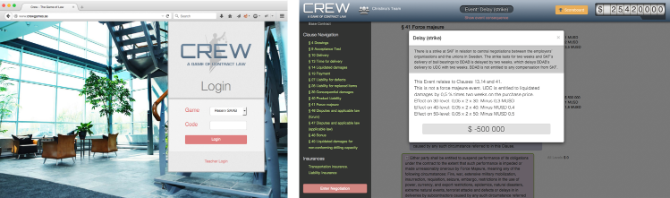

Example: Playing CREW, a Game for Enhanced Contract Learning ^

The participants work in teams and compete with other teams. Each team creates its own mix of contract terms by choosing from commonly used pre-set alternatives (buyer-friendly, seller-friendly or neutral). The less risk a team chooses, the more expensive it becomes and the less initial profit the team makes. This initial phase is interrupted by short mini-seminars where the game leader describes the law in relation to the alternatives. The mini-seminars are initiated by the participants’ questions in order to ensure maximum attention. At the next phase, the teams are exposed to events (delays, payment or quality problems, etc.). Then they apply their individual contract terms and see how the profit is affected by the events. The screenshots in Figure 2 show what appears on the login page and on a page where events have different effects on the profit, depending on the contract.

3.

Conclusions ^

4.

References ^

Agapiou, A., Maharg, P. & Nicol, E. (2010). Learning Contract Management and Administration Using a Simulated Game Environment. VIZ, IEEE 2nd International Conference in Visualisation 14–17 July 2009, pp. 114–120.

Aoki, K., Boyle, J. & Jenkins, J. (2008). Bound by Law? Tales from the Public Domain. New, expanded edition. http://www.thepublicdomain.org/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/bound-by-law-duke-edition.pdf [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Argyres, N. & Mayer, K. J. (2004). Learning to Contract: Evidence from the Personal Computer Industry. Organization Science, Vol. 15, Issue 4, July–August 2004, pp. 394–410.

Argyres, N. & Mayer, K. J. (2007). Contract Design as a Firm Capability: An Integration of Learning and Transaction Cost Perspectives. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 4, pp. 1060–1077.

Brown, L. M. (1950). Preventive Law. Prentice-Hall, Inc., New York, NY.

Brunschwig, C. R. (2001). Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen – legal design. (Doctoral dissertation). Zürcher Studien zur Rechtsgeschichte, Vol. 45. Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät d. Universität Zürich. Zurich: Schulthess Juristische Medien.

Brunschwig, C. R. (2011). Multisensory law and legal informatics – A comparison of how these legal disciplines relate to visual law, in: Jusletter IT 22 February 2011.

Brunschwig, C. R. (2014). On Visual Law: Visual Legal Communication Practices and Their Scholarly Exploration. In E. Schweighofer et al. (eds.), Zeichen und Zauber des Rechts: Festschrift für Friedrich Lachmayer. Editions Weblaw, Bern, pp. 899–933. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2405378 [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Burnham, S. J. (2003). How to read a contract. Arizona Law Review, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 133–172. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1960126 [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Cummins, T. (2003). Contracting as a Strategic Competence. International Association for Contract and Commercial Management IACCM.

Eppler, M. J. (2004). Knowledge communication problems between experts and managers. An analysis of knowledge transfer in decision processes. Paper # 1/2004. University of Lugano, Faculty of Communication Sciences, Institute for Corporate Communication. https://doc.rero.ch/record/5197/files/1_wpca0401.pdf [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Eppler, M. J. & Burkhard, R. A. (2004). Knowledge visualization. Towards a new discipline and its fields of application. ICA Working Paper #2/2004, University of Lugano. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.134.6040&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Erenli, K. (2015). Gamification and Law. On the Legal Implications of Using Gamified Elements. In T. Reiners & L. C. Wood (eds.), Gamification in Education and Business. Springer, Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London, pp. 535–552.

Goldman, P. (2008). Legal Education and Technology II: An Annotated Bibliography. Law Library Journal, Vol. 100, pp. 415–528. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1338741 [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Grimes, R. (2014). Introduction. In C. Strevens, R. Grimes & E. Phillips (eds.), Legal Education. Simulation in Theory and Practice. Ashgate, pp. 1–15.

Grossman, M. (2000). Contract negotiation crucial before website development. The Miami Herald, November 6.

Haapio, H. (1998). Quality Improvement through Proactive Contracting: Contracts Are Too Important to Be Left to Lawyers! Proceedings of Annual Quality Congress (AQC), American Society for Quality (ASQ), Philadelphia, PA, Vol. 52, May 1998, pp. 243–248.

Haapio, H. (2012). Making Contracts Work for Clients: towards Greater Clarity and Usability. In E. Schweighofer et al. (eds.), Transformation of Legal Languages. Proceedings of the 15th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2012. Band 288. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft, Wien, pp. 389–396.

Haapio, H. (2013a). Next Generation Contracts. A Paradigm Shift. Doctoral dissertation. Lexpert Ltd, Helsinki.

Haapio, H. (2013b). Visualising Contracts for Better Business. In D. J. B. Svantesson & S. Greenstein (eds.), Internationalisation of Law in the Digital Information Society. Nordic Yearbook of Law and Informatics 2010–2012. Ex Tuto Publishing, Copenhagen, pp. 285–310.

Haapio, H. & Siedel, G. J. (2013). A Short Guide to Contract Risk. Gower, Farnham.

Hagan, M. (2012). Contracts Law Dojo, http://www.lawschooldojo.com/contracts-law-dojo/ [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Hagan, M. (2013). Law Games, Law Simulations, http://www.lawschooldojo.com/law-games-law-simulations/ [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Hagan, M. (2014). Lightweight law games & Objection! Your Honor evidence game, http://www.openlawlab.com/2014/12/16/evidence-law-game-objection-honor/ [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Jüngst, H. E. (2010). Information Comics. Knowledge Transfer in a Popular Format. Leipziger Studien zur angewandten Linguistik und Translatologie, Vol. 7. Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main; New York.

Kimbro, S. (2014). Meaningful Play & Legal Games Research. Virtual Law Practice blog post, October 17, http://virtuallawpractice.org/3239/meaningful-play-legalgames/ [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Le Brun, M. (2003). Gaming Contract Law: Creating Pleasurable Ways to Learn the Law of Contract. eLaw Journal – Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, Vol. 10, No. 1, March, http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MurUEJL/2003/5.html [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Leff, A. A. (1970). Contract as thing. The American University Law Review, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 131–157.

Mahler, T. (2010). Legal risk management – Developing and evaluating elements of a method for proactive legal analyses, with a particular focus on contracts. Doctoral thesis. Faculty of Law, University of Oslo.

Mahler, T. (2013). A graphical user-interface for legal texts? In D. J. B. Svantesson & S. Greenstein (eds.), Internationalisation of Law in the Digital Information Society. Nordic Yearbook of Law and Informatics 2010–2012. Ex Tuto Publishing, Copenhagen, pp. 311–327.

Malhotra, D. (2012). Great deal, terrible contract: The case for negotiator involvement in the contracting phase. In B. M. Goldman & D. L. Shapiro (eds.), The Psychology of Negotiations in the 21st Century Workplace. New Challenges and New Solutions. Routledge, New York, NY, pp. 363–398.

Mitchell, C. (2013). Contract Law and Contract Practice. Bridging the Gap between Legal Reasoning and Commercial Expectation. Hart Publishing.

Passera, S. & Haapio, H. (2013). Transforming Contracts from Legal Rules to User-centered Communication Tools: a Human-Information Interaction Challenge. Communication Design Quarterly, Vol. 1, Issue 3, April, pp. 38–45.

Passera, S., Haapio, H. & Barton, T. (2013). Innovating Contract Practices: Merging Contract Design with Information Design. Proceedings of the IACCM Academic Forum on Contract and Commercial Management 2013, Phoenix, pp. 29–51.

Passera, S., Haapio, H. & Curtotti, M. (2014). Making the Meaning of Contracts Visible – Automating Contract Visualization. In E. Schweighofer et al. (eds.), Transparency. Proceedings of the 17th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2014. Band 302. Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG, Wien, pp. 443–450.

Pohjonen, S. (2006). Proactive Law in the Field of Law. In P. Wahlgren (ed.), Scandinavian Studies in Law, Vol. 49: A Proactive Approach. Stockholm Institute for Scandinavian Law, Stockholm, pp. 53–70. http://www.scandinavianlaw.se/pdf/49-2.pdf [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Pohjonen, S. (2009). Law and business – successful business contracting, corporate social responsibility and legal thinking. JFT – Tidskrift utgiven av Juridiska Föreningen i Finland, Vol. 145, No. 3–4, pp. 470–484. http://www.helsinki.fi/oikeustiede/omasivu/pohjonen/

Law%20and%20Business.pdf [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Ramberg, C. (2012). The Legal Practitioners’ Problems in Finding the Law Relating to CISG – Hardship, Defect Goods and Standard Terms. Scandinavian Studies in Law, Stockholm. Interface of Law pdf. http://www.christinaramberg.se/Download/bec170e5-34e5-44e4-8385-572a09ad4fc2 [Accessed January 5, 2015].

Siedel, G. J. & Haapio, H. (2010). Using proactive law for competitive advantage. American Business Law Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, 641–686. doi:10.1111/j.1744-1714.2010.01106.x.

Siedel, G. & Haapio, H. (2011). Proactive Law for Managers: A Hidden Source of Competitive Advantage. Gower, Farnham.

Wahlgren, P. (ed.) (2006). Scandinavian Studies in Law, Vol. 49: A Proactive Approach. Stockholm Institute for Scandinavian Law, Stockholm.

Wilson, J. M., Goodman, P. S. & Cronin, M. A. (2007). Group learning. Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, pp. 1041–1059.

Christina Ramberg, Professor, Stockholm University, Department of Law, Universitetsvägen 10A, 106 91 Stockholm, SE, christina.ramberg@juridicum.su.se; http://www.christinaramberg.se/CV?lang=eng

Helena Haapio, Business Law Teacher & Postdoctoral Researcher, University of Vaasa / International Contract Counsel, Lexpert Ltd, Pohjoisranta 20, 00170 Helsinki, FI, helena.haapio@lexpert.com; http://www.lexpert.com

- 1 Sample pages are presented at the web pages of the Program for Legal Technology & Design based out of Stanford University’s Institute of Design (d.school), http://www.legaltechdesign.com/reading-list. Further examples are available through http://www.lexpert.com/en/visualisation/ and http://www.lexpert.com/en/visualisation/visual1.htm.