1.

Introduction ^

Changing existing approach in design of the contracts is a crucial step for the paradigm shift. The existing templates and forms should be redesigned to produce contracts that are user-centred and usable – good contracts. Review of the relevant sources4 has shown that there are four main groups of criteria for good contracts that offer the methods and tools for making the contracts better: structure, content, language and design. The present research focuses on the last two of them: language and design (including layout and visualizations).

2.

Methodology ^

To further analyze how much better the new version of the contract is, compared to the traditional one, the comprehension and usability test was conducted. The test included two means of data collection: a questionnaire and subsequent discussion.

3.1.

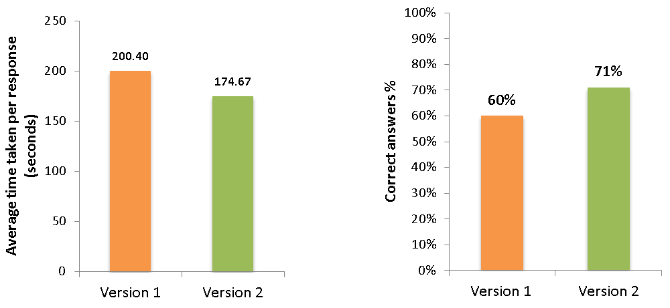

Speed and accuracy ^

3.2.

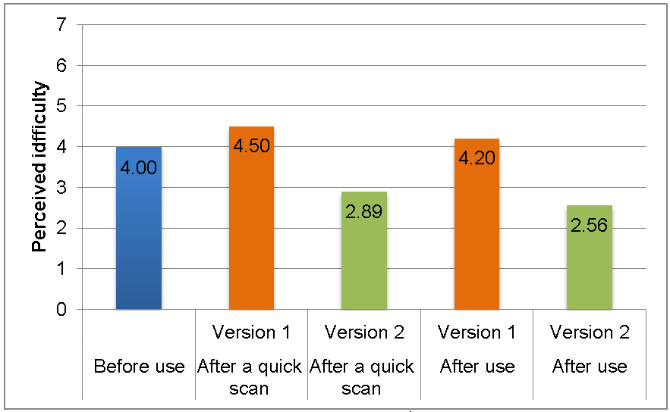

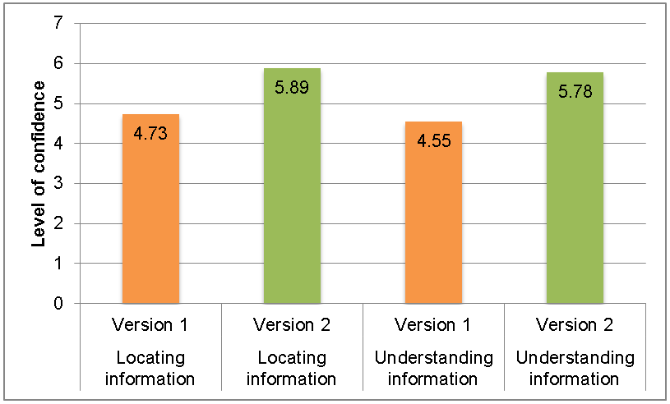

Perceived difficulty and confidence in future success ^

3.3.

User experience ^

Along with the general preference, participants were asked to indicate, which version of the commercial conditions they would prefer judging on particular aspects of the contract. As the table below shows, participants of the test preferred the modified versions regarding all the aspects.

| Preference of different aspects of a contract | ||

| Version 1 | Version 2 | |

| Presence of visualizations | 5% | 95% |

| Style of layout | 32% | 68% |

| Easier to read and skim through | 26% | 74% |

| Easier to understand | 0% | 100% |

Table 1. Preference of different aspects of the versions

While the average rating of all the aspects of the Version 1 is 2,7 on a 5-point scale (where 1 stands for «I didn’t like it at all» and 5 stands for «I liked it a lot»), the average for the Version 2 is 4,2.

| Evaluation of different aspects of a contract | ||

| Version 1 | Version 2 | |

| Look and feel | 2,8 | 4,4 |

| Style of layout | 2,9 | 4,0 |

| Language | 2,6 | 4,1 |

| Structure of the clauses | 2,7 | 3,7 |

| Presence of visualizations | 1,6 | 4,7 |

| Type size | 2,8 | 4,2 |

| Line spacing | 3,6 | 4,4 |

Table 2. Evaluation of different aspects of the versions

4.

Conclusions ^

5.

References ^

Barton, T., Berger-Walliser , G., & Haapio , H., Visualization: Seeing Contracts for What They Are, and What They Could Become. 19 Journal of Law, Business & Ethics, 47, pp. 47–63 (2013).

Berman, D., Toward a new format for Canadian legislation – Using graphic design principles and methods to improve public access to the law. Retrieved May 21, 2014, from davidberman.com: https://www.davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/NewFormatForCanadianLegislation.pdf (2000).

Bombardier Inc., About Us. Retrieved March 11, 2014, from bombardier.com: http://www.bombardier.com/en/about-us.html (2014).

Center for Plain Language, Write better. Retrieved April 16, 2014, from centerforplainlanguage.org: http://centerforplainlanguage.org/5-steps-to-plain-language/ (n.a.).

GLPI, & Schmolka, V., Results of Usability Testing Research on Plain Language Draft Sections of the Employment Insurance Act. Retrieved May 20, 2014, from davidberman.com: https://www.davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/glpi-english.pdf (2000).

Haapio, H., Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift. Helsinki, Finnland: Lexpert Ltd. (2013).

Haapio, H., Berger-Walliser, G., Walliser, B., & Rekola, K., Time for Visual Turn in Contracting? Journal of Contract Management, pp. 49–57. (2012).

Jacobson, S., A Checklist for Drafting Good Documents. Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors, Vol. 5, (2008).

James, N., Setting the standard: some steps toward a plain language profession. Sixth PLAIN conference. Amsterdam: Plain English Foundation. (2007).

Managing Industry-Changing Innovations, PRO2ACT. Retrieved July 11, 2014, from mindspace.fi: http://www.mindspace.fi/en/pro2act/ (2013a).

Managing Industry-Changing Innovations, UXUS. Retrieved July 11, 2014, from mindspace.fi: http://www.mindspace.fi/en/uxus/ (2013b).

Passera, S., 2012 16th International Conference on Information Visualization. Enhansing Contract Usability and User Experience Through Visualization. An experimental Evaluation. (pp. 376–382). Montpellier: IEEE. (2012).

Passera, S., & Haapio, H., Facilitating Collaboration Through Contract Visualization and Modularization. Proceedings of the 29th annual conference of the European Association of Cognitive Ergonomics ECCE. Rostock. (2011).

Passera, S., Haapio, H., & Barton, T., Innovating Contract Practices: Merging Contract Design with Information Design. Proceedings of the IACCM Academic Forum on Contract and Commercial Management 2013 (pp. 29–51). Phoenix. (2013a).

Passera, S., Pohjonen, S., Koskelainen, K., & Anttila, S., User-friendly Contracting Tools – A Visual Guide to Facilitate Public Procurement Contracting. Retrieved May 18, 2014, from mindspace.fi: http://www.mindspace.fi/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/User-friendly-contracting-tools_Passera-et-al_2013.pdf (2013b).

Perry, D., Ask the Expert – Improving Contract Clarity. Webinar. (IACCM, Interviewer) (2014).

Waller, R., What makes a good document? The criteria we use. Retrieved April 15, 2014, from http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC2CriteriaGoodDoc_v2.pdf (2011a).

Waller, R., The Clear Print standard: arguments for a flexible approach. Retrieved June 22, 2014, from simplificationcentre.org.uk: http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC10ClearPrint_v5.pdf (2011b).

WhiteMark, What are the Awards about? Retrieved April 18, 2014, from plainenglishawards.org.nz: http://plainenglishawards.org.nz/what-are-the-awards-about/ (2013a).

WhiteMark, Plain English criteria for documents and websites. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from plainenglishawards.org.nz: http://plainenglishawards.org.nz/plain-english-criteria/ (2013b).

Tetiana Mamula, Graduate master student, SRH Hochschule Berlin, Fregestrasse 7A, 12159 Berlin, DE, tetiana.mamula@gmail.com

Ulrich Hagel, Rechtsanwalt und Mediator, Senior Expert Dispute Resolution, Bombardier Transportation, Am Rathenaupark, 16761 Hennigsdorf, DE, ulrich.hagel@de.transport.bombardier.com

- 1 Cf. Haapio, H., Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift. Lexpert Ltd., Helsinki, Finnland. p. 2–3, (2013).

- 2 Cf. Haapio, H., Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift. Lexpert Ltd., Helsinki, Finnland. p. 2, (2013). Stark, D., & Choplin, J., Dysfunctional Contracts and the Laws and Practices That Enable Them: An Empirical Analysis. Retrieved July 14, 2014, from works.bepress.com: http://www.works.bepress.com/debra_stark/6/ (2012).

- 3 Cf. Haapio, H., Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift. Lexpert Ltd., Helsinki, Finnland. p. 71, (2013).

- 4 Cf. for example: James, N., Setting the standard: some steps toward a plain language profession. Sixth PLAIN conference. Amsterdam: Plain English Foundation. (2007). Waller, R., What makes a good document? The criteria we use. Retrieved April 15, 2014, from http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC2CriteriaGoodDoc_v2.pdf (2011a). WhiteMark, Plain English criteria for documents and websites. Retrieved April 17, 2014, from plainenglishawards.org.nz: http://plainenglishawards.org.nz/plain-english-criteria/ (2013b).

- 5 Bombardier Inc., About Us. Retrieved March 11, 2014, from bombardier.com: http://www.bombardier.com/en/about-us.html (2014).

- 6 Cf. GLPI, & Schmolka, V., Results of Usability Testing Research on Plain Language Draft Sections of the Employment Insurance Act. Retrieved May 20, 2014, from davidberman.com: https://www.davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/glpi-english.pdf (2000). Managing Industry-Changing Innovations, PRO2ACT. Retrieved July 11, 2014, from mindspace.fi: http://www.mindspace.fi/en/pro2act/ (2013a). Managing Industry-Changing Innovations, UXUS. Retrieved July 11, 2014, from mindspace.fi: http://www.mindspace.fi/en/uxus/ (2013b). Passera, S., 2012 16th International Conference on Information Visualization. Enhansing Contract Usability and User Experience Through Visualization. An experimental Evaluation. (pp. 376–382). Montpellier: IEEE. (2012).