1.

The C4E project ^

2.

Prerequisites for a PCP tender ^

The C4E procuring partners decided to implement the Lead Tendering Authority model with Agency for Digital Italy (AGID) as Lead Tendering Authority.

2.1.

Legal barriers ^

2.2.

Contractual Framework ^

2.3.

Governance ^

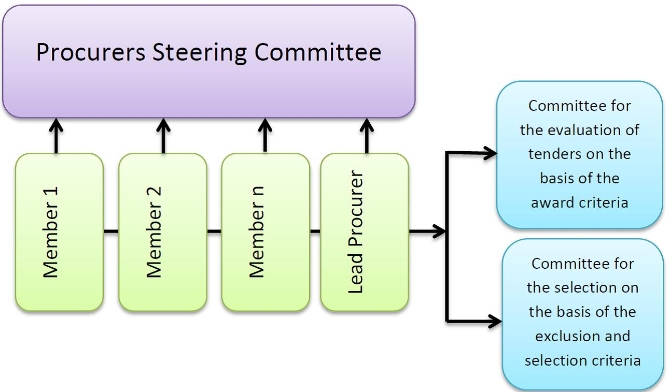

The governance structure foresees a Procurers Steering Committee as well as a number of independent evaluation committees; the latter depending on the number of lots the tender is divided.

2.4.

Open versus restricted procedures ^

3.1.

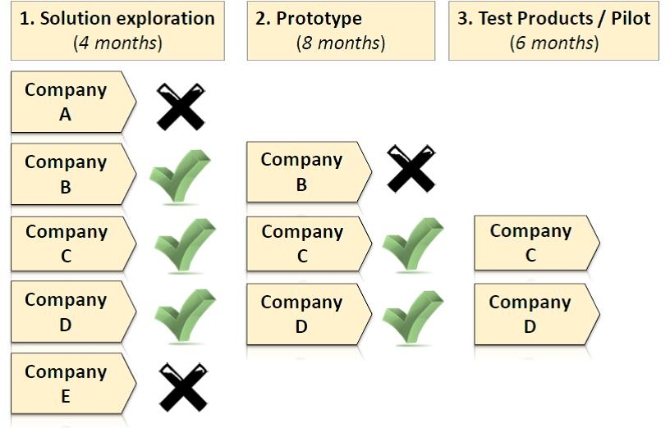

Phased process ^

3.2.

Tender Regulation ^

3.3.

Framework Agreement ^

3.4.

Public Procurement Legislation ^

4.

Recommendations ^

5.

References ^

Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM(2007) 799 final, Pre-commercial Procurement: Driving innovation to ensure sustainable high quality public services in Europe.

Directive 2004/18/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 March 2004 on the coordination of procedures for the award of public works contracts, public supply contracts and public service contracts.

Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement and repealing Directive 2004/18/EC.

Heijboer, Govert/Telgen, Jan, Choosing the open or the restricted procedure: a big deal or a big deal?, Journal of Public Procurement, Vol. 2, Issue 2, 2002.

Legislative Decree no. 163/2006, Informazioni circa i mancati inviti, le esclusioni e le aggiudicazioni [Informations regarding missing invitation, exclusions and awarding], Article 79 [as provided by article 41 of 2004/18/EC].

- 1 As the public sector is the largest buyer of ICT in Europe, the public sector can drive the widespread adoption of cloud computing.

- 2 Joint PCP Agreement (the Joint PCP Agreement or the Procurement Agreement) is the contract between the Lead Tendering Authority (Agenzia per L’Italia Digitale – AGID) and the other Contracting Authorities (The Ministry of Financial Affairs, Directoraat Generaal Belastingdienst, Entidade de Serviços Partilhados da Administração Pública, I.P (ESPAP), Institutul National de Cercetare-Dezvoltare in Informatica – ICI Bucuresti and Ministerstvo financií Slovenskej republiky), which lays down the practical modalities governing the «Joint PCP Procedure».

- 3 Directive 2004/18/EC, Article 39.

- 4 Heijboer Govert & Jan Telgen, 2002, Page 187–216.

- 5 COM(2007) 799 final.

- 6 Example of a possible approach for procuring R&D services applying risk-benefit sharing at market conditions, i.e. PCP, http://cordis.europa.eu/pub/fp7/ict/docs/pcp/pcp-brochure_en.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2016).

- 7 Legislative Decree no. 163/2006, Article 79.

- 8 Directive 2014/24/EU.

- 9 The competitive procedure with negotiation may be used when justified by the specific circumstances in relation to the nature, complexity or the legal and financial make-up of a given project, or by the fact that the needs of the contracting authority cannot be met by an «off the shelf» type of solution.

- 10 The compulsory acceptance of self-declarations from bidders is introduced (through a standardized European Single Procurement Document) and only the winning bidder will have to submit formal evidence (certificates and attestations). Also, the minimum deadlines to submit tenders are shortened.

- 11 The turnover requirements will be limited to a maximum of twice the estimated value of the contract, except in duly justified cases.