1.

Introduction ^

Design thinking is already present in many areas of life, including various scientific disciplines. However, unfortunately, in the field of contract drafting, it is still on a very primitive stage. The research on contract design is very modest and is mostly limited to individual case studies.1 At the same time, areas of information and knowledge design that can offer a number of useful methods and tools, which can be used in the contract drafting procedure, are already quite developed.

2.

Design of good contracts ^

2.1.

Page features ^

When talking about the page features of traditional contracts, the first problem that comes to mind is the overwhelming underestimation of the role of white space for the readability of documents. White space is a blank area on the page with no type on it. [Felker et al. 1981, 81] It is essential to leave enough white space within the page, as it brings attention to the important pieces of information and gives opportunities for the readers’ eyes to rest. [Berman 2000, 25] Graphic designers recommend that the proportion of text and white space in legal documents should be 50:50. [Robbins 2004, 113] In order to achieve this, the contract drafter should apply larger margins, larger spaces between paragraphs and after headings, as well as larger line spacing. [Felker et al. 1981, 81–83] Using bullet point lists and visualizations also helps to create more white space on the page. There is no perfect use of white space: it all depends on the particular document. However, it is always necessary to keep in mind that if there is too little white space on the page, it is less likely that the reader will want to read the document.

2.2.

Typography ^

2.2.1.

Typeface ^

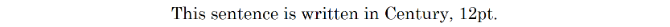

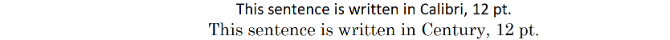

The majority of traditional contracts uses the most conservative typefaces Times New Roman and Arial. However, these two fonts are being seriously criticized by typography professionals. [e.g., Felici 2003, 70; Butterick 2010, 84, 110] They are considered to be crowded and difficult to read. At the same time, there is no single opinion about the perfect typeface that should be used in contracts. Matthew Butterick, the author of «Typography for Lawyers», recommends the use of the typeface Equity of his own production. [Butterick 2014c] Nevertheless, such an approach is widely criticized, [e.g., Glover 2012] as this typeface is not initially installed on computers – it needs to be bought online additionally. Therefore, most of the contract's users don’t work with it. Generally, it is recommended to use system fonts that work across all computers and are widely available in order to avoid problems with sharing documents inside and outside the company. [e.g., Adams 2013, 380; Berman 2000, 17] Wordsmith Associates Communication Consulting advises using Palatino, Book Antiqua, Garamond or Times. [Wordsmith Associates Communication Consultants Inc. 2014] Kenneth A. Adams prefers Calibri. [Adams 2013, 379] David Berman chose Century Oldstyle and Frutiger for the modified version of the Canadian Employment Insurance Act. His choice was explained by a set of criteria: the typeface should be not ubiquitous, have a neutral emotional tone, should be reproduced easily on different systems, have efficient width and lower x-height. [Berman 2000, 17–19]

2.2.2.

Type size ^

Therefore, it is recommended to choose the point size according to the visual size rather than point size. [Butterick 2014f; Felker et al. 1981, 77] There is a type of font measurement, which is more specific than a point size and shows the visual size of letters. It is called x-height (see figure 1).

This approach helps to get a feeling for the advised type size and provides room for benchmarking.

2.2.3.

Line length ^

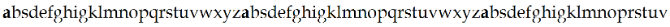

Overlong lines are one of the most common problems of contract layout. [Waller 2011a, 15] Too many characters per line make reading tiring, and the reader gets lost in the middle of the line. At the same time, it is important to avoid too short lines, as a text divided into columns, in which the readers eye has to move to the next line too often affects comprehension. The optimal line length is considered to be 50–70 characters per line, which corresponds 10–12 words per line. [e.g., Berman 2000, 20; Butterick 2010, 142; Felker et al. 1981, 74] Another way to measure the appropriate line length is the «alphabet test», offered by Matthew Butterick in his blog: a good line length should fit between two and three English alphabets, [Butterick 2014e] like here:3

2.3.

Highlighting ^

2.3.1.

Bold face, italic and underlining ^

2.3.2.

Capitalization ^

2.3.3.

Colour ^

There is a number of other highlighting techniques that also can be used. One of them is the use of borders. This technique serves especially well for highlighting definitions: a contract drafter can put a border around a provision, so it appears to be in a box. [Adams 2013, 385] Even white space can be used as a highlighting technique (see 2.1. Page Features).

3.

Conclusions ^

4.

Limitations ^

While this study focuses on the contract design, it is important to remember that this is only one of the aspects that influence contract readability and usability. Among other characteristics that make a document more simple and, therefore, more attractive for non-legal users are language, content, and structure.4

5.

References ^

Adams, Kenneth A., A Manual Style for Contract Drafting, 3rd Edition ed., American Bar Assosiation, Chicago 2013.

Adams, Kenneth A., Adams on Contract Drafting, from adamsdrafting.com: http://www.adamsdrafting.com/ (accessed on 10 December 2015), 2014.

Barton, Tim, Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde, & Haapio, Helena, Visualization: Seeing Contracts for What They Are, and What They Could Become, 19 Journal of Law, Business & Ethics, 47, 2013, p. 47–63.

Bernstein, Gregg R., The Fine Print: Redesigning Legal Contracts for the Digital Environment, from typographichub.org: http://typographichub.org/images/uploads/downloads/the_fine_print.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2015), 2011.

Berman, David, Toward a new format for Canadian legislation – Using graphic design principles and methods to improve public access to the law, from davidberman.com: https://www.davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/NewFormatForCanadianLegislation.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2015), 2000.

Butterick, Mattew, Typography for Lawyers, Jones McClure, 2010.

Butterick, Mattew, All caps, from typographyforlawyers.com: http://typographyforlawyers.com/all-caps.html (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2014a.

Butterick, Mattew, Bold or italic, from typographyforlawyers.com: http://typographyforlawyers.com/bold-or-italic.html (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2014b.

Butterick, Mattew, Equity: a font for lawyers, from typographyforlawyers.com: http://typographyforlawyers.com/ (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2014c.

Butterick, Mattew, Font recommendations, from typographyforlawyers.com: http://typographyforlawyers.com/font-recommendations.html (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2014d.

Butterick, Mattew, Line Length, from typographyforlawyers.com: http://typographyforlawyers.com/line-length.html (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2014e.

Butterick, Mattew, Point size, from typographyforlawyers.com: http://typographyforlawyers.com/point-size.html (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2014f.

Center for Plain Language, Write better, from centerforplainlanguage.org: http://centerforplainlanguage.org/5-steps-to-plain-language/ (accessed on 4 December 2015).

Felici, J., The Complete Manual of Typography: A Guide to Setting Perfect Type, 2nd edition ed., Peachpit Press, Berkeley 2003.

Felker, Daniel B., et al., Guidelines for Document Designers, American Institutes for Research, Washington DC 1981.

Glover, S., Normal People (and Lawyers) Shouldn’t Buy Fonts, from lawyerist.com: http://lawyerist.com/39472/normal-people-lawyers-shouldnt-buy-fonts/#more-39472 (accessed on 15 December 2015), 2012.

GLPI & Schmolka, Vicki, Results of Usability Testing Research on Plain Language Draft Sections of the Employment Insurance Act, https://www.davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/glpi-english.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2015), 2000.

Haapio, Helena, Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift, Lexpert Ltd, Helsinki 2013.

Haapio, Helena, Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde, Walliser, Bjorn, & Rekola, Katri, Time for Visual Turn in Contracting?, Journal of Contract Management, Summer 2012, Vol. 10, NCMA, 2012, p. 49–57.

IACCM, Contract Design Award Program, from iaccm.com: https://www.iaccm.com/services/contractdesign/ (accessed on 17 December 2015), 2014.

Jacobson, Samuel, A Checklist for Drafting Good Documents, Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors, Vol. 5., 2008, p. 79–117.

Mamula, Tetiana, Hagel, Ulrich, The Design of Commercial Conditions – Layout, Visualization, Language. In: Schweighofer/Kummer/Hötzendorfer (eds.), Co-operation. Proceedings of the 18th Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2015, books@ocg.at, Wien 2015, p. 471–478.

Passera, Stefania, Enhansing contract usability and user experience through visualization. An experimental evaluation, 16th International Conference on Information Visualization, IEEE, Montpellier 2012, p. 376–382.

Passera, Stefania, Haapio, Helena, & Barton, Tim, Innovating Contract Practices: Merging Contract Design with Information Design. Proceedings of the IACCM Academic Forum on Contract and Commercial Management 2013, Phoenix, 2013, p. 29–51.

Plain English Foundation, Welcome – Plain English Foundation, from plainenglishfoundation.com: http://www.plainenglishfoundation.com/home (accessed on 4 December 2015), 2014.

Plain Language Association International (PLAIN), Home. Plain Language Association International (PLAIN), from plainlanguagenetwork.org: http://www.plainlanguagenetwork.org/index.html (accessed on 5 December 2015), 2014.

Pohjonen, Soile, Proactive Contracting: In Contracts between Businesses, Ius Gentium, Journal of the University of Baltimore, Center for International and Comparative Law, vol. 12 (Agreements), Baltimore 2006, p. 155–183.

Robbins, Ruth Anne, Painting with Print: Incorporating Concepts of Typographic and Layout Design into the Text of Legal Writing Documents, Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors, Vol. 2, West, A Thomson Business, Eagan 2004, p. 108–150.

Wordsmith Associates Communication Consultants Inc., We’re not your old English teacher, from wordsmithassociates.com: http://wordsmithassociates.com/index.html (accessed on 6 December 2015), 2014.

Waller, Rob, The Clear Print standard: arguments for a flexible approach, from simplificationcentre.org.uk: http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC10ClearPrint_v5.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2015), 2011a.

Waller, Rob, What makes a good document? The criteria we use, from http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC2CriteriaGoodDoc_v2.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2015), 2011b.

- 1 Cf. e.g. GLPI/Schmolka, Results of Usability Testing Research on Plain Language Draft Sections of the Employment Insurance Act, https://www.davidberman.com/wp-content/uploads/glpi-english.pdf (accesed on 29 November 2015), 2000; Mamula/Hagel, The Design of Commercial Conditions – Layout, Visualization, Language. In: Schweighofer/Kummer/Hötzendorfer (eds.), Co-operation. Proceedings of the 18th Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2015, books@ocg.at, Wien 2015, p. 471–478; Passera, Enhansing contract usability and user experience through visualization. An experimental evaluation, 16th International Conference on Information Visualization, IEEE, Montpellier 2012, p. 376–382.

- 2 In the light of this discussion, the British organization called Simplification Centre definitely stands aside. As its primary goal is to simplify complicated communication, it offers a more significant research in the field of contract simplification. The web page of the Simplification Centre is regularly updated, including its blog, list of technical papers and reports from events. For more information see: www.simplificationcentre.org.uk

- 3 This line is written using Palatino typeface, font size 12,5

- 4 For more information about characteristics of user-friendly contracts see e.g.: Center for Plain Language, Write better, from centerforplainlanguage.org: http://centerforplainlanguage.org/5-steps-to-plain-language/; Felker et al., Guidelines for Document Designers, American Institutes for Research, Washington DC 1981; Jacobson, A Checklist for Drafting Good Documents, Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors, Vol. 5., 2008, p. 79–117; IACCM, Contract Design Award Program, from iaccm.com: https://www.iaccm.com/services/contractdesign/, 2014 etc.

- 5 For more information about contract visualizations see e.g.: Barton et al., Visualization: Seeing Contracts for What They Are, and What They Could Become, 19 Journal of Law, Business & Ethics, 47, 2013, p. 47–63; Haapio et al., Time for Visual Turn in Contracting?, Journal of Contract Management, Summer 2012, Vol. 10, NCMA, 2012, p. 49–57; Passera, Enhansing contract usability and user experience through visualization. An experimental evaluation, 16th International Conference on Information Visualization, IEEE, Montpellier 2012, p. 376–382.

![Figure 1: Point size and x-height [Waller 2011a, 5]](/magnoliaAuthor/.imaging/stk/jusletterit/content/dam/publicationsystem/articles/Jusletter-IT/2016/IRIS/design-of-good-comme_9994edddbb/images/Tsygankova_TT_Abb.-1/jcr:content/1517889428Grafik2.png.png)