1.

The Challenges of Financial Regulation ^

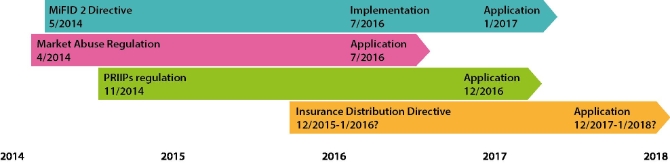

In the end of the 2000s the world economy faced its worst financial crisis since 1929. Failures of corporate governance in the financial sector were one significant reason for the crisis. Risk assessment efforts failed for all market participants: investors, financial firms as well as their supervisors. The characteristics of the new highly complex financial products were not properly understood by financial firms’ management or their owners.1 The EU reacted to the crisis by creating a mass of new financial markets regulation. During the past few years approximately 80 new statutes concerning financial markets have been enacted. This creates major challenges especially for small and medium-size actors.2 New fundamental regulation will still be issued concerning, for example, investment advice. The renewed Directive on Markets in Financial Instruments (MiFID), Market Abuse Regulation, Insurance Distribution Directive and new regulation on Key Information Documents for packaged retail and insurance-based products (PRIIPs) are going to be applied in the near future, as shown in Figure 1 below.

1.1.

Complexity Caused by the Quantity and Quality of Regulation ^

The implicit assumption behind the ever-growing EU-regulation on financial markets seems to have been: the more information the better. However, information is only effective when it is understood and used. For those who are regulated, additional compliance costs and comprehension challenges are caused by the complexity of the information. This stems not only from the quantity but also from the quality and understandability of the information.

The EU has recently paid attention to the overwhelming EU legislation through its Regulatory Fitness and Performance (REFIT) program. According to the European Commission’s Better Regulation Guidelines, the Commission should prepare «well-drafted, high quality legal texts that are easy to understand and implement».3 The European Economic and Social Committee (EESC) has noted that a proactive approach4 should be applied in order to achieve better lawmaking. Instead of focusing on failures, EU legislation should aim at securing future success. Better regulation, simplification and communication have been promoted by different EU instances as main policy objectives in completing the Single Market.5 A Joint Practical Guide is intended to provide assistance for those who are involved in drafting. The Guide states that legal acts should be drafted clearly, simply and precisely,6 which includes avoiding unnecessary elements, uncertainty and ambiguity. Good drafting is extremely important in Union level regulation, which must fit to the complex, multicultural and multilingual system. The persons to whom the regulations are intended to apply as well as the persons responsible for putting the regulations into effect should be taken into account in drafting.7

1.2.

Struggling with Complexity – Investors’ Perspective ^

From the perspective of investor protection, the main response to the financial crisis has been the introduction of new disclosure mandates. Disclosures are intended to prepare people for complex decisions which can be unfamiliar to them. Disclosure mandates have good aims, yet investors8 do not always benefit from them. Investors can be lazy decision-makers and overlook and skip prospectuses and other information:9 the British Financial Services Authority (now Financial Conduct Authority) has observed that the core problem concerning disclosure regulation is that people do not read the material.10 No matter how informative the disclosures might be, they do not serve their aim if they are not utilized. Even when people read the information, they do not always understand it.11 A research area called behavioral finance has focused on the cognitive limitations of financial actors. Investors as well as other actors of the financial markets are affected by cognitive biases in their decision making. They can be overly optimistic about what they know, or stress information that confirms their intrinsic choices.12

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority, EIOPA, has noted that lengthy disclosures are being superseded by an approach which takes into account the presentation of information based on insights into consumer behavior and cognition. Certain styles of presenting information may help to counter cognitive biases that distort decision making.13 EIOPA lists among its strategic goals preventive consumer protection which aims at anticipating future problems rather than merely reacting to the past.14 In this paper, we take this approach one step further and focus on an approach that might be called proactive investor protection. Instead of problems, our perspective is positively oriented towards making information more usable and useful. As the EESC put it, «A piece of legislation is not the goal; its successful implementation is». Implementation should be understood broadly, not just as enforcement by institutions but also as acceptance and resulting change of behaviors.15

2.

Overcoming Complexity by Visualization and Simplification ^

Recent research points to the direction that merging Proactive Law with a new, user-centred approach to information design can enable overcoming many of the complexity challenges. Research and case studies carried out in the context of legislation16 and contracts17 demonstrate how changing their design and the ways in which they are communicated can lead to better comprehension and enhanced usability. Contracting is an essential element of financial markets. Obtaining financial products actually means contracting. According to PRIIPs Regulation (Art. 6), a key information document is a pre-contractual document. In a broad sense, investment products are contracts, some even by name.18

There are several proactive suggestions for reducing the current complexity. In the following we focus on simplification and visualization. These approaches can reduce the readers’ cognitive load and thus the barriers to effective communication.19 Together, they are important parts of a broader move toward improved decision making and better investors’ choices. Section 3 will offer examples where these approaches have been implemented.

2.1.

The Possibilities of Simplification and Visualization ^

Information design scholarship recognizes two main approaches to the simplification of complex information: optimization, which includes plain language and clear typography that improve but may not fundamentally change a given document; and transformation, which includes a range of more radical strategies such as distillation, abstraction, layering and visualization.26 Visualization employs images to supplement text. Graphs, charts, timelines, diagrams, flowcharts, decision trees - all of these and more can depict information into more easily digestible formats. In the context of contracts, the aims of visualization have been summarized to include, for example:

- Clarifying what written language does not manage to fully explain;

- Making the logic and structure of the documents more visible;

- Giving both overview and insight into complex terms and processes;

- Supporting evidence, analysis, explanation, and reasoning in complex settings;

- Providing an alternative access structure to the contents, especially to the non-experts working with the document;

- Engaging stakeholders who have been alienated by the conventional look and feel.27

2.2.

SPs and KIIDs as First Steps toward More Usable Investor Information ^

Before the introduction of the KIIDs the European Commission commissioned investor research into how information should be presented in a KIID in order to be used and comprehended by investors. The research suggested that the first impression of the document is important and that dense texting is off-putting. Plenty of white space and a few core messages were found to be more effective than a mass of information. The design should be attractive and aid the core message to stand out from other marketing material. The language used should be clear and plain. The length of the document is also important, as too lengthy documents can be avoided by investors.31

The use of simplified documents is going to be extended to packaged retail and insurance-based investment products (PRIIPs). The regulation on Key Information Documents (KIDs) will be applied from the end of 2016 (PRIIPs regulation). KIDs are intended to be simple and standardized documents which give key facts of the product. According to the regulation, the format, presentation and content of the information of KIDs must be carefully calibrated in order to maximise the understanding and usage of information. Under Art 6 of PRIIPs regulation, a KID should be a short document, maximum three A4 pages. The layout must be constructed in a way that is easy to read, and the language used should be clear and comprehensible, with a focus on key information that retail investors need. Draft regulatory technical standards and a preliminary KID template were published in November 2015. The European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) are expected to submit finalized standards to the EU Commission by the end of March 2016.32

3.

Toward More Usable Financial Information ^

The emergence of KIIDS and KIDS deserves notion as a landmark process within the EU financial markets law.35 Both were preceded by extensive consumer testing, the studies indicating clearly that consumers prefer simpler documents: bullet points are preferred to full paragraphs and dense texting. Simpler documents were also associated with better understanding of the content and visuals were much appreciated.36

The current prospectuses on complex financial products are often far from consumer-friendly with their long and extremely dense text. After 2016, these products are mandated to follow the new KID format. The Figure below (Figure 2) shows a prototype of the layout of a KID document produced following the draft regulatory technical standards by ESAs. Figure 3, in turn, illustrates a crucial part of the template, a summary risk indicator, which is intended to help investors in choosing and comparing products.37 Visualization and simplification efforts are prevalent in the draft template.38

Figure 3: The Format for Presenting a Summary Risk Indicator39

Our example concerns investor information. Visualization and simplification can be used in a similar manner for example for internal guidance and even regulation.40 Simplified briefings of regulations would be welcome among the users of the financial markets regulation. Some signs of this kind of progression can be seen in MiFID II technical standards composed by ESMA (European Securities and Markets Authority). The technical standards themselves and documents related to them are exhaustingly long. However, ESMA has created short briefings for some central stakeholder groups.41

4.

Conclusion ^

5.

References ^

Atkinson, Adele/Messy, Flore-Anne (2012). Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD / International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study, OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions, No. 15, OECD Publishing.

Ben-Shahar, Omri/Schneider, Carl E. (2014). More Than You Wanted to Know. Failure of Mandated Disclosure, Princeton University Press.

CESR (2010). CESR’s template for the Key Investor Information document, CESR/10-1321.

EBA (2015). Joint Committee launches discussion on PRIIPs key information documents, https://www.eba.europa.eu/-/joint-committee-launches-discussion-on-priips-key-information-documents (accessed on 22 October 2015).

EESC (2009). Opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee on «The proactive law approach: a further step towards better regulation at EU level», 2009/C 175/05.

EIOPA (2014). What will change with the Key Information Document, https://eiopa.europa.eu/consumer-protection/consumer-lounge/what-will-change-with-the-key-information-document (accessed on 8 December 2015).

EIOPA (2015). EIOPA and supervisory convergence – The beginning of a new journey, EIOPA 5th annual conference, Welcome speech by Gabriel Bernardino, 18th November 2015.

ESAs (2015). Joint Consultation Paper, PRIIPs Key Information Documents, Draft regulatory technical standards.

ESMA (2015). ESMA readies MiFID II, MAR and CSDR, https://www.esma.europa.eu/news/ESMA-readies-MiFID-II-MAR-and-CSDR, 28 September 2015.

European Commission (2015). Better Regulation Guidelines on preparing proposals, implementation, and transposition, http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/guidelines/ug_chap4_en.htm (accessed on 22 October 2015).

European Commission (2007). Exposure Draft. Initial orientations for discussion on possible adjustments to the UCITS Directive. 5. Simplified prospectus – Investor disclosure regime, Brussels.

European Commission (2014). DG Justice Guidance Document.

European Parliament, the Council and the Commission (2014). Joint Practical Guide for persons involved in the drafting of European Union legislation, Brussels.

Federation of Finnish Financial Services (2015). Statement concerning REFIT program of the EU. FK:n lausunto valtioneuvoston kanslian kartoituspyyntöön paremmasta sääntelystä. VNEUS2015-00471.

Felsenfeld, Carl/Siegel, Alan (1981). Writing Contracts in Plain English. West Publishing Co.

Finnish Financial Supervisory Authority (2014). Capital redemption contracts, http://www.finanssivalvonta.fi/en/Financial_customer/Financial_products/Investments/Capital_redemption/Pages/Default.aspx (accessed on 3 December 2015).

FSA (2003). Informing consumers: product disclosure at the point of sale, Consultation Paper 170.

García, María José Roa (2013). Financial Education and Behavioral Finance: New Insights Into the Role of Information in Financial Decisions, Journal of Economic Surveys.

Haapio, Helena/Barton Thomas, D. (forthcoming), Business-Friendly Contracting: How Simplification and Visualization Can Help Bring It to Practice. Forthcoming, Springer.

Hagan, Margaret (2013). Illustrated Law Flow Charts, http://www.margarethagan.com/drawings/illustrated-law-flow-charts/ (accessed 3 December 2015).

Hetrick, Patrick K. (2008). Drafting common interest community documents: Minimalism in an era of micromanagement. Campbell Law Review, Vol. 30, Issue 3, Spring, pp. 409–435.

IFF Reseach and YouGov, UCITS (2009). Disclosure Testing Reseach Report, prepared for European Commission.

Kimble, Joseph (2006). Lifting the Fog of Legalese. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Kimble, Joseph (2012). Writing for Dollars, Writing to Please. The Case for Plain Language in Business, Government, and Law. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Lannerö, Pär (2013). Fighting the Biggest Lie on the Internet. Common terms beta proposal, Metamatrix Stockholm, 30 April 2013, www.commonterms.net/commonterms_beta_proposal.pdf (accessed 5 January 2016).

London Economics (2015). Consumer testing study of the possible new format and content for retail disclosures of packaged retail and insurance-based investment products, Final Report.

Magnusson Sjöberg, Cecilia (2008). Proactive ICT Law in the Nordic Countries. In A Proactive Approach to Contracting and Law. Ed. Haapio. IACCM & Turku School of Applied Sciences.

Mitchell, Jay A. (2015). Putting some product into work-product: corporate lawyers learning from designers, Berkeley Business Law Journal, vol. 12, pp. 1–44.

Moloney, Niamh (2014). EU Securities and Financial Markets Regulation, Third Edition, Oxford EU Law Library.

Passera, Stefania (2015). Beyond the wall of text: how information design can make contracts user-friendly, in: Lecture Notes on Computer Science 9187 – Design, User Experience, and Usability: Users and Interactions (Part II).

Passera, Stefania/Haapio, Helena (2013). Transforming Contracts from Legal Rules to User-centered Communication Tools: a Human-Information, Interaction Challenge, Communication Design Quarterly, Vol. 1, Issue 3.

Passera, Stefania/Haapio, Helena/Barton, Thomas D. (2013). Innovating Contract Practices: Merging Contract Design with Information Design, in Proceedings of the 2013 IACCM Academic Forum on Integrating Law and Contract Management: Proactive, Preventive and Strategic Approaches, Ridgefield, CT: IACCM.

Siedel, George/Haapio, Helena (2010). Using proactive law for competitive advantage, American Business Law Journal, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 641–686.

Siegel, Alan/Etzkorn, Irene (2013). Simple. Conquering the Crisis of Complexity. New York & Boston: Twelve.

The de Larosière Group (2009). The High-Level Group on Financial Supervision in the EU, Brussels, http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/finances/docs/de_larosiere_report_en.pdf (accessed 22 October 2015).

US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) (2011). CFPB Aims to Simplify Credit Card Agreements. Agency Announces Plans to Pilot Test Prototype Agreement; Invites Public to Weigh In, 7 December 2011.

Waller, Rob (2015). Layout for legislation, Simplification Centre, Technical Paper 15, available at http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/resources/technical-papers/ (accessed 7 January 2016).

Waller, Rob (2011(a)). Information design: how the disciplines work together. Technical paper 14. Simplification Centre, http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/downloads/papers/SC14DisciplinesTogether.pdf (accessed 14 December 2015).

Waller, Rob (2011(b)). Simplification: what is gained and what is lost. Simplification Centre Technical Paper 1, available at http://www.simplificationcentre.org.uk/resources/technical-papers/ (accessed 7 January 2016).

Weatherley, Steve (2005). Pathclearer: A More Commercial Approach to Drafting Commercial Contracts. PLC Law Department Quarterly, October–December, pp. 39–46.

- 1 The de Larosière Group 2009, p. 6, 8, 10.

- 2 See, e.g., Federation of Finnish Financial Services 18 September 2015, p. 1–2.

- 3 European Commission 2015, Better Regulation Guidelines Guidelines on preparing proposals, implementation, and transposition, available at http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/guidelines/toc_guide_en.htm.

- 4 For Proactive Law and its origins in Proactive Contracting and the Nordic School of Proactive Law, see, e.g., Siedel/Haapio 2010, Magnusson Sjöberg 2008, p. 43–56.

- 5 EESC Opinion 2009, 4.2. Especially the European Commission, the European Parliament and the EESC have argued for these goals.

- 6 European Parliament, the Council and the Commission 2014, Joint Practical Guide 2014, p. 7.

- 7 Id. p. 7, 9.

- 8 In this paper, «investors» refers to «retail clients» as defined in MiFID 2 (Art 4).

- 9 Ben-Shahar/Schneider 2014, p. 4, 8–10.

- 10 FSA 2003, 6.

- 11 Ben-Shahar/Schneider 2014, p. 55.

- 12 See, e.g., García 2013, p. 1–7.

- 13 EIOPA, What will change with the Key Information Document, https://eiopa.europa.eu/consumer-protection/consumer-lounge/what-will-change-with-the-key-information-document.

- 14 EIOPA 2015, p. 6.

- 15 EESC Opinion 2009, 2.5.

- 16 See, e.g., Waller 2015.

- 17 See, e.g., Passera 2015. See also Haapio/Barton (forthcoming).

- 18 For example, capital redemption contracts. See, e.g., Finnish Financial Supervisory Authority 2014.

- 19 See, e.g., Passera 2015, Passera/Haapio 2013.

- 20 Felsenfeld/Siegel 1981, Kimble 2006 and 2012.

- 21 Waller 2011a and 2011b.

- 22 Hetrick 2008.

- 23 Weatherley 2005 and Siedel/Haapio 2010.

- 24 US Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) 2011 and Siegel/Etzkorn 2013.

- 25 For a summary, see Lannerö 2013; for updates, see Related Work, http://commonterms.org/Related.aspx.

- 26 Waller 2011b.

- 27 Passera/Haapio/Barton 2013.

- 28 European Commission 2007, Exposure Draft, 5.

- 29 Committee of European Securities Regulators, now ESMA.

- 30 CESR’s template for the Key Investor Information document 2010.

- 31 IFF Research and YouGov 2009, 6, p. 153–154.

- 32 EBA 2015, Joint Committee launches discussion on PRIIPs key information documents. UCITS are coming under the same regulation after a transition period of five years.

- 33 See, e.g,. FundConnect, http://fundconnect.com/products-services/kiid-services.html and Kii Hub, http://www.kiihub.com/.

- 34 In addition to KIDs, the EU has paid attention to helping implementation within its recent Directive on Consumer Rights. The Guidance created includes an optional model for presenting information on digital products. The model includes a collection of illustrative icons. DG Justice Guidance Document 2014, p. 70–72.

- 35 See, e.g., Moloney 2014, p. 250–253.

- 36 London Economics 2015, xii, p. 193–194, 196. See also IFF Research and YouGov 2009.

- 37 Draft regulatory technical standards by ESAs, 2015, p. 49.

- 38 The official template is expected to be published in the Spring of 2016.

- 39 Excerpt from the format for the presentation of a Summary Risk Indicator shown in Id., p. 49.

- 40 See, e.g., Margaret Hagan’s Illustrated Law Flow Charts.

- 41 See, https://www.esma.europa.eu/news/ESMA-readies-MiFID-II-MAR-and-CSDR.

- 42 See, e.g., Atkinson/Messy 2012, p. 7-8.

- 43 Mitchell 2015, p. 13, 23, 21.