1.1.

A soft law instrument ^

Rec(2004)11 defines e-voting as an e-election or e-referendum that involves the use of electronic means at least in the casting of the vote covering e-voting in controlled environments (e.g. voting machines in polling stations) and from uncontrolled ones (e.g. voting via internet) [12][22].

As for voting at polling stations or postal voting, a legal framework is an indispensable precondition to the use of e-voting with binding effect in political elections2 [2][24]. It contains the requirements governing such use. Legal requirements (must) determine e-voting characteristics.

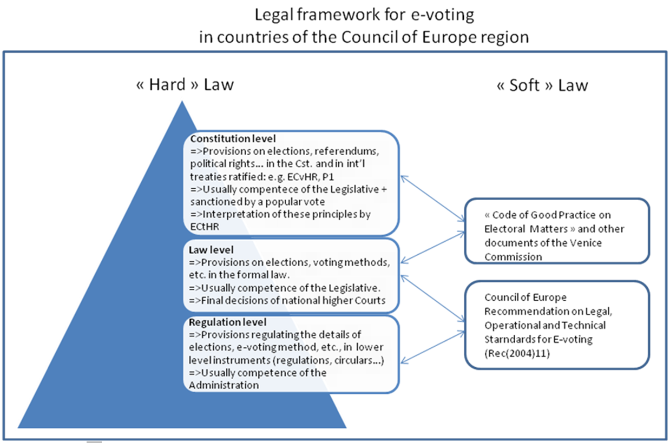

In a specific country, the legal framework for e-voting is composed of provisions contained in mandatory (or «hard» law) instruments that stand in a hierarchical relationship to each other (Figure 1). In addition, non mandatory or «soft» law instruments, do also impact e-voting.

Several Council of Europe instruments have a direct or indirect impact on the legal framework for elections and e-voting in countries of the region. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECvHR) and in particular art. 3 of Protocol 1 (right to free elections), are part of the higher level principles governing elections (and e-voting) in countries that have ratified them [14] and so is the interpretation of the principles by the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

Soft law instruments, such as the opinions of the European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission) are closely related to national hard law. For instance, the Code of Good Practice on Electoral Matters – a soft law instrument – both reflects and influences national legislations. It reflects national hard law (or is influenced by it) to the extent that it picks up and catalogues the main, commonly shared principles of the European Electoral Heritage to be found in national legislations and practice. On the other hand, it influences the content of hard law to the extent that it serves as a benchmark to countries and other institutions when amending or evaluating legal provisions on elections or when interpreting treaty provisions such as those of ECvHR.

Rec(2004)11 is a soft law instrument of a lower level than the Code of Good Practice on Electoral Matters. It aims at translating the commonly shared electoral principles (catalogued in the Code) into standards specific to e-voting. Rec(2004)11 was influenced by nascent national legislation on internet voting, in particular the 2002 Swiss federal ordinance on e-voting [13]. It has had a direct impact on e-voting in countries where it has been included in the national legislation on e-voting aswas the case in Norway where the Recommendation was (almost entirely) given the status of legal basis regulating internet voting [20][12]. Elsewhere, although Rec(2004)11 is not directly part of the national legislation on e-voting, it has (had) an effect on it. Countries and organizations have referred to Rec(2004)11 when interpreting [23][18] or amending hard law instruments [5]. It has also served as a benchmark when making practical decisions on e-voting3 or when evaluating its set-up and use [21].

1.2.

Need to update Rec(2004)11 ^

The intrinsic grounds include congenital weaknesses of the Recommendation such as vagueness, lacunae, inconsistencies, over- or under-specifications, redundancy and repetition of provisions (see in particular references [16] and [19] and the in-depth discussion in [13]). Extrinsic reasons include the need to take into account relevant developments in national legislations and case-law [11], taking advantage of practical and academic experience accumulated since the adoption of the original Recommendation, addressing the implications of emerging technical concepts and solutions, such as individual and/or public end-to-end (E2E) verifiability, among others.4

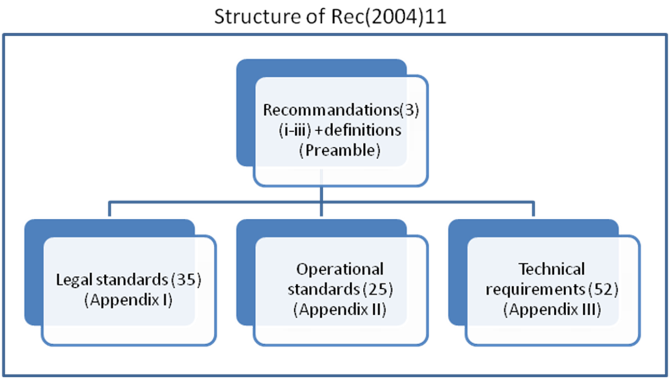

In this section we will discuss one of the intrinsic reasons, namely the need to improve the structure of Rec(2004)11 to ensure a good interweaving of legal, operational and technical requirements. One of the identified problems with the current Recommendation is that it contains 112 legal, operational and technical standards and requirements without it being clear how they relate to which other: which are the broader, high-level ones, and which those of a more executive nature.5 As illustrated by Figure 2, the three appendices are situated at the same level giving the impression that their provisions are of the same level, which is not the case.

2.1.

A roadmap for the update ^

As shown by the expert report that discusses the replies to the questionnaire6 [10] and its annexes, all proposals to clarify the scope and format of the Recommendation received a majority of approval (from 72 to 84% of yes replies). An analysis of negative opinions shows that most are based on a different understanding of the question or simply present alternative views rather than opposition. The alternative and negative replies underline important aspects that in any case need to be taken in consideration. The report furthermore proposed the introduction of a review mechanism which is currently missing.

2.2.

A new definition of e-voting and other clarifications ^

2.3.

A new structure for Rec(2004)11 ^

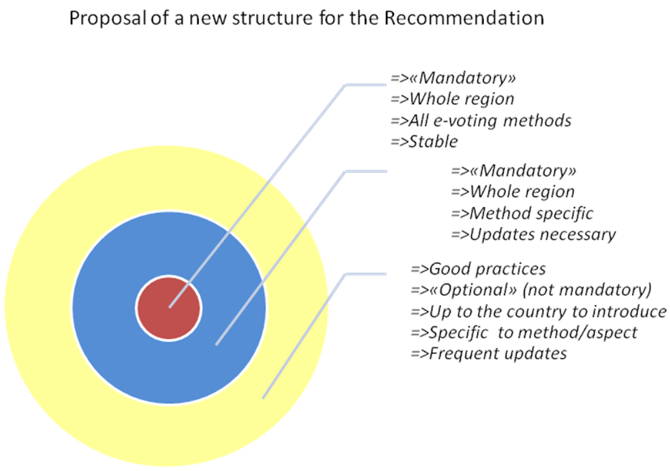

Countries have expressed interest in a collection of up-to-date good practices developed in the region. Such a good practice for instance could be the development of e-voting specific certification criteria and the effective certification of e-voting systems against them [27]. Good practice examples are not «mandatory» to the region. They serve as inspiration to countries which consider introducing them. Furthermore they are supposed to evolve. The non-«mandatory» nature and the need for frequent updates justify the fact of putting such examples in yet another layer (represented by the outside, yellow layer in fig.3). Without being part of the Recommendation strictly speaking, such a layer has clear links to it. When a good practice becomes widespread enough as to be considered regional standard, it can move to the blue layer.

2.4.

A review mechanism ^

3.1.

Increasing dependence on ICT ^

A lack of global vision is observed in some cases of e-voting introduction, not only in the regulatory area. E-voting is often treated as an ad-hoc project, especially during the initial, usually small-scale deployment phase. In our view, authorities in charge of e-voting have all interest in embedding it as soon as possible in a larger context and treating it as part of a bigger challenge.

The context is that of election administration in its broadest sense and the challenge relates to the increasing use of electronics in all phases of the electoral process [11][21], independently from the use or not of e-voting. To this must be added the increasing dependence of election administration on ICT: voter and candidate registration, transmission and tabulation of results, their publication, etc., are based and depend on ICT solutions. The question is how to manage e-voting in order to benefit from the advantages they offer (e.g., e-voting provides an effective voting channel to people with disabilities or to expatriates, or makes voting attractive to youngsters) while acknowledging, mitigating and controlling the associated risks.

3.2.

Evolution of national legislations and case law ^

3.3.

«Detailed regulation of e-voting» vs «Risk of weakening legal principles» ^

4.

References ^

Internet sources were last accessed on 9 January 2016

[1] Barrat, J. and Goldsmith, B. (2012) Compliance with International Standards, Norwegian e-vote project, http://www.regjeringen.no/upload/KRD/Prosjekter/e-valg/evaluering/Topic7_Assessment.pdf

[2] Braun, N. (2004) «E-Voting: Switzerland’s Projects and their Legal Framework – in a European Context» in Prosser, A. and Krimmer, R. (Eds.) Electronic Voting in Europe. Technology, Law, Politics and Society, Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI) – Proceedings Series of the Gesellschaft für Informatik (GI), Volume P-47, pp. 43–52.

[3] Bundesverfassungsgericht (2009), Decision 2 BvC 3/07, 2 BvC 4/07, of 3 March 2009, http://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/entscheidungen/cs20090303_2bvc000307.htm

[4] Commission des lois constitutionnelles du Sénat français/Anziani, A. and Lefèvre A. (2014) Rapport d’information no 445 (2013–2014) sur le vote électronique, http://www.senat.fr/rap/r13-445/r13-445.html

[5] Conseil fédéral/Suisse (2013) Rapport du Conseil fédéral sur le vote électronique. Evaluation de la mise en place du vote électronique (2006–2012) et bases de dévelopment, du 14 juin 2013, http://www.bk.admin.ch/themen/pore/evoting/07977/index.html?lang=fr

[6] Council of Europe (2011) Certification of e-voting systems, Guidelines for developing processes that confirm compliance with prescribed requirements and standards, http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/themes/evoting/CoEvotingCertification_en.pdf

[7] Council of Europe (2011) Guidelines on transparency of e-enabled elections, http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/themes/evoting/CoEenabledElections_en.pdf

[8] Council of Europe (2004) Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member states on legal, operational and technical standards for e-voting, adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 30 September 2004, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=778189

[9] Council of Europe (2004) Explanatory Memorandum to the Draft Recommendation Rec(2004)11 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on legal, operational and technical standards for e-voting, https://wcd.coe.int/ViewDoc.jsp?id=778189

[10] Driza Maurer, A. (2015) Report on the scope and format of the update of Rec(2004)11, http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/Themes/evoting/CAHVE/CAHVE-2015-2add.pdf

[11] Driza Maurer, A., Barrat J. (eds.) E-Voting Case Law. A Comparative Analysis Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Surrey, England 2015

[12] Driza Maurer, A. (2014) «Ten Years Council of Europe Rec(2004)11» in Krimmer, R., Volkamer, M.: Proceedings of Electronic Voting 2014 (EVOTE2014), TUT Press, Tallinn, p. 111–117

[13] Driza Maurer, A. (2013) Report on the possible update of the Council of Europe Recommendation Rec(2004)11 on legal, operational and technical standards for e-voting, 29 November 2013, http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/themes/evoting/2013ARDITA.pdf

[14] European Commission for Democracy through Law (Venice Commission)/Grabenwarter, Ch. (2004) Report on the compatibility of remote voting and electronic voting with the standards of the Council of Europe, http://www.venice.coe.int/webforms/documents/CDL-AD(2004)012.aspx

[15] Jones, D., Simons B. (2012) Broken Ballots. Will your vote count? CSLI Publications, Center for the Study of Language and Information, Leland Stanford Junior University, U.S.A. 2012

[16] Jones, D. (2004) The European 2004 Draft E-Voting Standard: Some critical comments, http://homepage.cs.uiowa.edu/~jones/voting/coe2004.shtml

[17] Loeber, L. (2008) «E-Voting in the Netherlands; from General Acceptance to General Doubt in Two Years» in Krimmer, R. and Grimm, R. (Eds.) (2008) Electronic Voting 2008 (EVOTE08), Lecture Notes in Informatics (LNI) – Proceedings Series of the Gesellschaft für Informatik (GI), Volume P-131

[18] Madise, Ü. and Vinkel, P. (2011) «Constitutionality of Remote Internet Voting: The Estonian Perspective», Juridica International. Iuridicum Foundation, Vol. 18, pp. 4–16.

[19] McGaley, M. and Gibson, J.P. (2006) A Critical Analysis of the Council of Europe Recommendations on e-voting, https://www.usenix.org/legacy/event/evt06/tech/full_papers/mcgaley/mcgaley.pdf

[20] Norway (2013) Regulations relating to trial internet voting during advance voting and use of electronic electoral rolls at polling stations on election day during the 2013 parliamentary election in selected municipalities, http://www.regjeringen.no/upload/KRD/Kampanjer/valgportal/Regelverk/Regulations_relating_to_trial_internet_voting_2013.pdf

[21] OSCE/ODIHR (2013) Handbook for the observation of new voting technologies, http://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/104939

[22] Remmert, M. (2004) «Towards European Standards on Electronic Voting», in Prosser, A. and Krimmer, R. (Eds.), Electronic Voting in Europe – Technology, Law, Politics and Society, P-47, Gesellschaft für Informatik, pp. 13–16.

[23] Republic of Estonia, Supreme Court (2005) Judgment of the Constitutional Review Chamber of the Supreme Court, Decision 3-4-1-13-05, 1st September 2005, http://www.nc.ee/?id=381

[24] Schwartz, B. and Grice, D. (2013) Establishing a legal framework for e-voting in Canada, http://www.elections.ca/res/rec/tech/elfec/pdf/elfec_e.pdf

[25] U.S. Election Assistance Commission (EAC) (2005) 2005 Voluntary Voting System Guidelines, http://www.eac.gov/assets/1/workflow_staging/Page/124.PDF

[26] Verfassungsgerichtshof (2011) Decision V 85‐96/11‐15, 13 December 2011, http://www.vfgh.gv.at/cms/vfgh-site/attachments/7/6/7/CH0006/CMS1327398738575/e-voting_v85-11.pdf

[27] Volkamer, M. (2009) Evaluation of Electronic Voting, Requirements and Evaluation Procedures to Support Responsible Election Authorities, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2009

[28] Wenda, G., Stein, R. «The Council of Europe and e-voting: History and impact of Rec(2004)11» in Krimmer, R., Volkamer, M.: Proceedings of Electronic Voting 2014 (EVOTE2014), TUT Press, Tallinn, p. 105–110

- 1 The author of this paper is the nominated leading legal expert of the ad-hoc Committee of Experts on E-voting (CAHVE) created in April 2015 at the Council of Europe. More on: http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/news/2015/CAHVE2910_en.asp.

- 2 «Elections» will be used here as a broad term covering all kinds of political votes: election of candidates, votes on issues (e.g. on initiatives and referendums).

- 3 A useful source of information are the country reports at the biannual review meetings organized since 2004. They can be found under «Biannual Review Meetings» at http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/themes/evoting/default_en.asp.

- 4 For a summary, see the report of the expert meeting of 2013 at http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/themes/evoting/Rec-2004-11-2013-Informal_en.pdf.

- 5 Recommendation ii specifically says that «the interconnection between the legal, operational and technical aspects of e-voting, as set out in the appendices, has to be taken into account…». It has so far been interpreted as meaning only that a country should consider requirements in all three appendices and not limit its considerations to some of them.

- 6 The expert report was discussed at the first plenary meeting of CAHVE, held in Strasbourg on 28-29 October 2015. More on the dedicated page of the Council of Europe, Electoral Assistance and Census Division: http://www.coe.int/t/DEMOCRACY/ELECTORAL-ASSISTANCE/news/2015/CAHVE2910_en.asp.