1.

Introduction ^

Standard form contracts trace back to the 19th century. In the age of industrialisation, entering into contracts has been accompanied by the unilateral use of pre-formulated rules tailored to one party’s own interests and thus resulting in an imbalance of powers between the contracting parties [Zerres, 2014]. Today, customers are confronted with standard form contracts every day in form of Terms of Services (ToS), for example when they buy something online or register for an online service. Studies with more than 45'000 participants have shown that only 0.1% to 0.2% of customers read ToS of online shops [Bakos et al., 2014]. While standard form contracts regularly reflect an imbalance of contracting power, this imbalance is even stronger in situations where one of the contracting parties is a consumer without a professional legal background and the other one is a company with a potentially huge legal department. The relevance of this is visible by the amount of jurisprudence in this area, comprising more than 28’000 judgments in Germany only [Juris, 2017]. Therefore, in this paper, we present an approach to use Artificial Intelligence (AI) to empower customers of web shops to make educated decisions about where to buy or not by automatically identifying Terms of Services of German web shops, assessing their content regarding lawfulness and customer friendliness, as well as summarising them in a simplified language in order to make them understandable for non-legal-experts.

2.

Related Work ^

In order to create these summaries, a system first has to obtain the relevant information from the text. Information Retrieval (IR) for legal texts has gained a lot of attraction in recent years. Examples are McCallum [2015], Grabmair et al. [2015], and Francesconi et al. [2010], or, for German texts, Walter and Pinkal [2006], and Waltl et al. [2010]. The issue of simplifying legal texts was, e.g. addressed by Bhatia [1983] and Collantes et al. [2015].

3.

Customer Perspective ^

4.1.

Imbalance of powers ^

4.2.

Reasons ^

4.3.

«SaToS» approach ^

4.4.

Act of Out-of-Court Legal Services ^

5.

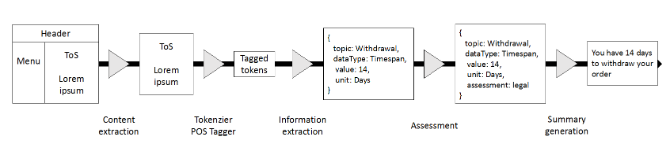

Technical Approach ^

This stripped and annotated version of the text can then be used to extract relevant information (like the time of withdrawal). Currently, our system uses a rule-based approach for extraction. Some of the rules we developed to extract the necessary information are shown in Table 1.

| Topic | Rules (translated from German) |

| Right of warranty | – warranty . . . ([0-9]* | [one | two | . . . ]) [day(s) | month(s) | year(s)] AND used OR NOT used (goods | products) -warranty . . . used (goods | products) . . . excluded |

| Right of withdrawal | – product . . . original (packaging | packed | . . . ) . . . (return | send back)– original (packaging | packed | . . . ) . . . (return | send back) |

| Period of withdrawal | – withdraw . . . ([0-9]* | [one | two | . . . ]) [day(s) | month(s) | year(s)] |

| Obligation to inspect product | – warranty . . . [inspect|report] AND NOT merchant |

| Risk of loss | – [risk of loss | bearing the risk] . . . [shipped | carriage of goods] . . . consumer |

Table 1: Extraction rules for ToS (excerpt)

6.

Evaluation ^

6.1.

ToS Classification ^

We collected a dataset of 3’424 URLs. 2’592 from ToS pages, manually labeled by a price comparison website, and 832 from other webshop pages. We split the dataset into training (200 ToS and 200 Other) and test (2’392 ToS and 632 Other). The results of the evaluation are shown in Table 2. It is obvious, that the ML approach performed significantly better, with regard to precision, recall, and F-score. Given the fact, that the ML classifier was trained with a relatively small, non-optimized dataset, the results are promising, keeping in mind that we use an online learning approach and expect the system to improve over time. One might wonder, why one should use a hybrid approach, although ML performs better in every category. The fifth column in Table 2 shows the average time in seconds, that was needed to classify a URL. If successful, the rule-based approach is significantly faster and hence preferable.

| Approach | Precision | Recall | F-score | Øt in s |

| ML | 0.9115 | 0.8219 | 0.8644 | 1.435 |

| Rule-based | 0.7953 | 0.5393 | 0.6428 | 0.001 |

| Approach | Precision | Recall | F-score | Øt in s |

| ML | 0.9115 | 0.8219 | 0.8644 | 1.435 |

| Rule-based | 0.7953 | 0.5393 | 0.6428 | 0.001 |

Table 2: Evaluation ToS Classification

6.2.

Information Extraction ^

In order to get a first idea about the quality of the information extraction of our prototype, we randomly picked 20 ToS from the above mentioned dataset of ToS pages. We asked a legal professional to manually extract the information, which our current prototype is able to extract (i.e. right of withdrawal and warranty period). In this way, for each ToS up to five pieces of information were manually extracted (time of withdrawal, warranty period for consumer new good, warranty period of consumer used good, warranty period of tradesperson new good, warranty period of tradesperson used good). Afterwards, we ran our tool on the same ToS and compared the results. The result of the comparison is shown in Table 3. If the manually and automatically extracted information is equal, the information was correctly extracted. If the automatically extracted information differs from the manually extracted information (e.g. withdrawal period of 14 instead of 30 days), it is classified as wrongly extracted information. If information was extracted manually for a topic but not automatically, it is classified as missing information. In no case, information that was not extracted manually was extracted automatically.

| Topic | Correctly extracted information | Wrongly extracted information | Missing information |

| Withdrawal | 18 | 1 | 0 |

| Warranty | 41 | 3 | 4 |

Table 3: Evaluation Information Extraction

7.

Conclusion ^

8.

References ^

Bakos, Yannis/Marotta-Wurgler, Florencia/ Trossen, David, Does anyone read the fine print? Consumer attention to standard-form contracts, The Journal of Legal Studies, 2014, Issue 43, p. 1–35.

Beater, Axel, Verbraucherschutz und Schutzzweckdenken im Wettbewerbsrecht, Mohr Siebeck, 2000, p. 117.

Bhatia, Vijay, Simplification v. easification-the case of legal texts. Applied linguistics, Volume 4:42, 1983.

Binns, Reuben/Matthews, David, Community structure for efficient information flow in «tos; dr», a social machine for parsing legalese, In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web, ACM, 2014, p. 881–884.

Collantes, Miguel/Hipe, Maureen/Sorilla, Juan Lorenzo/Tolentino, Laurenz/Samson, Briane, Simpatico, A text simplification system for senate and house bills, In Proceedings of the 11th National Natural Language Processing Research Symposium, 2015, p. 26–32.

Fleischer, Holger, Informationsasymmetrie im Vertragsrecht, Doctoral dissertation, Universität zu Köln, 2001.

Francesconi, Enrico/ Montemagni, Simonetta/Peters, Wim/Tiscornia, Daniela, Semantic processing of legal texts: Where the language of law meets the law of language, Volume 6036. Springer, 2010.

Gatt, Albert/Reiter, Ehud, SimpleNLG: A realisation engine for practical applications, Proceedings of the 12th European Workshop on Natural Language Generation, Association for Computational Lingustics, 2009.

Grabmair, Matthias/Ashley, Kevin/Chen, Ran/Sureshkumar, Preethi/Wang, Chen/Nyberg, Eric/Walker, Vern, Introducing luima: an experiment in legal conceptual retrieval of vaccine injury decisions using a uima type system and tools, In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Law, ACM, 2015, p. 69–78.

Juris Rechtsinformationsdatenbank, https://www.juris.de/r3/search, last visited on 29 October 2017.

Kocher, Eva, Funktionen der Rechtsprechung, Mohr Siebeck, 2007, p. 48.

Lippi, Marco/Palka, Przemyslaw/Contissa, Giuseppe/Lagioia, Francesca/Micklitz, Hans-Wolfgang/Panagis, Yannis/Sartor, Giovanni/Torroni, Paolo, Automated Detection of Unfair Clauses in Online Consumer Contracts, Legal Knowledge and Information Systems, 2017, p. 145–154.

McCallum, Andrew, Information extraction: Distilling structured data from unstructured text, Queue, Issue 3(9), 2005, p. 48–57.

Oehler, Andreas, Verbraucher und Recht (VuR), Nomos, 2006, p. 294.

Reichardt, Vanessa, Der Verbraucher und seine variable Rolle im Wirtschaftsverkehr, Duncker & Humblot, 2008, p. 47.

Schirmbacher, Martin, Verbrauchervertriebsrecht, Nomos, 2005, p. 124.

Tamm, Marina, Verbraucherschutzrecht, Mohr Siebeck, 2011, p. 19.

Walter, Stephan/Pinkal, Manfred, Automatic extraction of definitions from german court decisions, In Proceedings of the workshop on information extraction beyond the document, ACL, 2006, p. 20–28.

Zerres, Thomas, Principles of the German law on standard terms of contract, Jurawelt, 2014.

Waltl, Bernhard/Landthaler, Jörg/Scepankova, Elena/Matthes, Florian/Geiger, Thomas/Stocker, Christoph/Schneider, Christian, Automated Extraction of Semantic Information from German Legal Documents. In: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter/Sorge, Christoph (Eds.), Trends and Communities of Legal Informatics, Tagungsband des 20. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik Symposions IRIS 2017, books@OCG, Wien 2017, p. 217–224.

Zimmermann, Reinhard, The New German Law of Obligations, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 165.

- 1 Council Directive 93/13/EEC of 5 April 1993 on unfair terms in consumer contracts, OJ L 95/29 of 21 April 1993.

- 2 Art. 20 Abs. 3 GG (Grundgesetz – German Constitution), https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/index.html (all websites last visited in January 2018).

- 3 https://www.flightright.de/.

- 4 Cf. German Constitutional Court BVerfGE 89, 214 of 19 October 1993.

- 5 https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_rdg/index.html.

- 6 Cf. § 8 Abs. 1 Nr. 4 Act of Out-of-Court Legal Services.