1.

Introduction ^

- Data that are used especially for training and evaluation of machine learning based systems are more easily available in digital form

- High performance computing infrastructure

- Efficient algorithms that can automate increasingly complex tasks

1.1.

AI in the Legal Domain and the Expanding Use of Algorithmic Decision Making ^

- The ability to easily understand and follow knowledge representation, and

- The explainability and transparency of decisions.

1.2.

The Need for More Algorithmic Transparency ^

1.3.

The Opacity of Algorithmic-Decision-Making Software ^

In recent years, we have witnessed the birth of the subfield of interpretable machine-learning. We are already seeing important advances in the field. Jung et al., for example, proposed simple rules for bail decisions7. Corbett-Davies et al. recently discussed the fairness of such algorithms8. Legislators are also working towards building legal frameworks that can help prevent algorithms from creating undesired results, such as discrimination9. Latest discussions in politics and societal pressure even caused legislators to examine the potentials of governing ADM in the field of discrimination. This can, for example, be observed in Germany, the ministry of justice announced a project on a feasibility study on governing ADM10.

1.4.

The Role of Explanations within a Complex Process ^

There are commonly adapted frameworks to describe the phases involved in creating a system, which can decide autonomously. Figure 2 shows a process, which consists of five subsequent phases. This represents a model process for illustration purposes, which does not contain any iterations and feedback loops. In practical applications the process is typically more complex (Waltl, Landthaler, et al., 2017). During each phase, activities are automatically performed and intermediate results are produced that influence the overall ADM.

Figure 1: ADM is a complex process of at least five different phases (Fayyad, Piatetsky-Shapiro, & Smyth, 1996).

2.1.

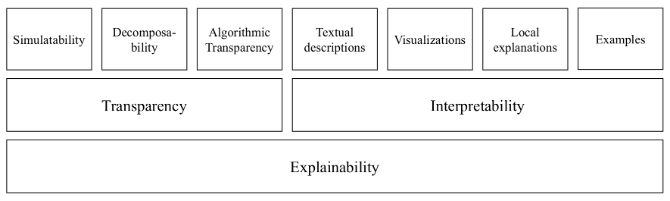

Trying to Capture the Essence of Explainability ^

- Formal and unambiguous representation

- Descriptive nature of the representation

- Output of a classifier with regard to a decision

- Current and prior input of the classifier

- Why did that output happen?

- Why not some other output?

- For which cases does the machine produce a reliable output?

- Can you provide a confidence score for the machine’s output?

- Under which circumstances, i.e. state and input, can the machine’s output be trusted?

- Which parameters effect the output most (negatively and positively)?

- What can be done to correct an error?

- provision of textual descriptions of how a model behaves and how specific features contribute to a classification,

- visualizations as dense representations of features and their contexts,

- local explanations providing information about the impact of one particular feature, and finally, and

- examples that illustrate the internal structure of a trained model.

2.2.

Expanding Comparability Dimensions of Machine Learning Algorithms for ADM ^

Machine learning algorithms, which are powering many of the artificial intelligence systems at issue here, can be analyzed along different parameters and dimensions. Kotsiantis proposed a comparison chart which has become widely accepted (Kotsiantis, 2007). Table 1 below shows the dimensions that Kotsiantis proposed. We adapted the table to the research question of this article. The columns list six common machine learning algorithms, and the rows describe the desirable property of the specific machine learning algorithm.

| Decision Trees | Neural Networks | Naïve Bayes | kNN | SVM | Deductive logic based11 | |

| Accuracy | • • | • • • | • | • • | • • • | • • |

| Speed of learning | • • • | • | • • • • | • • • • | • | • • |

| Speed of classification | • • • • | • • • • | • • • • | • | • • • • | • • • • |

| Tolerance w.r.t. input | • • • | • • | • | • | • • • • | • • |

| Transparency of the process | • • • • | • • | • • • | • • | • • | • • • |

| Transparency of the model | • • • • | • | • • | • • • | • • | • • • • |

| Transparency theof classification | • • • • | • | • • • | • • • | • | • • • • |

Table 1: Extension of comparison of common machine learning algorithms based on Kotsiantis (2007).

- Transparency of the process: The ability of explain refers to the entire process of ADM, which consists of different steps that are all based on individual design decisions. So, to what degree can an ADM process be made transparent and explainable? This refers mainly to the structure of the classification process (see Section 4). Developing a machine learning classifier does not only require the training of a machine learning classifier. It also requires that parameterization of the algorithm, data collection, pre-processing, etc. Throughout the parameterization process many parameters have to be set. For example, decision trees, including random forests, can be parameterized to have a maximal depth. This is known as «pruning», which helps explain the impact of a particular parameter on the trained model. In addition, human biases can influence the data collection which in turn can influence the training and the classification of the model12.

- Transparency of the model: To what degree can the model underlying a trained classifier be made transparent and be communicated clearly to humans? In most implementations of machine learning classifiers, the internal representation of the trained model is stored very monolithically, which does not facilitate deeper understanding of the trained model. Classifiers, such as decision trees or deductive logic based systems, represent their decision structures in rules that can be analyzed and interpreted by humans. More elaborate classifiers such as Naïve Bayes or SVMs13 rely on a more elaborate mathematical representation, mainly optimizing of probabilities or a so-called kernel function. These internal representations require much more effort to understand and interpretation. Finally, neural networks tend to have a very complex internal structure, including large amount of so-called «hidden layers,» that make the underlying decision-making process very hard to interpret and comprehend. For every classifier, the reasoning structure is highly rational, albeit in a very formal mathematical sense, which frequently does correspond with what engineers and users would deem acceptable clarity.

- Transparency of the classification: To which degree can a classified instance of a trained classifier be made transparent and be communicated? In addition to the transparency of the underlying knowledge on which a model is trained, the transparency of the classification used plays an important role. Given a concrete classification that lead to a specific algorithmic decision, to what degree can the classifier itself make the factors transparent that lead to the specific decision? What were the features that contributed to a specific decision and what was the concrete weight of their contribution? This should also take into account whether a feature contributed directly or indirectly (by influencing other features) to the overall classification. This should not only complement the transparency of the model but should also have an impact on future research and systems engineering. There may be instances where the transparency of the model may not be important at all, while the reproducibility of a decision can be critical.

2.3.

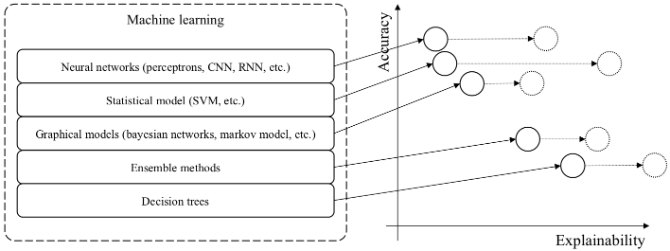

Explainability as an Intrinsic Property of Machine Learning Algorithms ^

Figure 3: Explainability of machine learning classifiers as desirable property based on Gunning (2017).

3.

Conclusion ^

4.

References ^

Ashley, K. D. (2017). Artificial Intelligence and Legal Analytics: New Tools for Law Practice in the Digital Age. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bellman, R. (1978). An Introduction to Artificial Intelligence: Can Computers Think?: Boyd & Fraser.

Bench-Capon, T., Araszkiewicz, M., Ashley, K., Atkinson, K., Bex, F., Borges, F., . . . Wyner, A. (2012). A history of AI and Law in 50 papers: 25 years of the international conference on AI and Law. Artificial Intelligence and Law.

Doshi-Velez, F., Kortz, M., Budish, R., Bavitz, C., Gershman, S., O’Brien, D., . . . Wood, A. (2017). Accountability of AI Under the Law: The Role of Explanation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.01134.

Fayyad, U., Piatetsky-Shapiro, G., & Smyth, P. (1996). From data mining to knowledge discovery in databases. AI magazine, 17(3), 37.

Fiedler, H. (1990). Entmythologisierung von Expertensystemen In H. Bonin (Ed.), Einführung in die Thematik für Recht und öffentliche Verwaltung. Heidelberg: Decker & Müller-Verlag.

Goodman, B., & Flaxman, S. (2016). European Union regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a «right to explanation». arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.08813.

Gunning, D. (2017). Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)

Hendricks, L. A., Akata, Z., Rohrbach, M., Donahue, J., Schiele, B., & Darrell, T. (2016). Generating Visual Explanations. Paper presented at the ECCV.

Kotsiantis, S. B. (2007). Supervised Machine Learning: A Review of Classification Techniques. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 2007 conference on Emerging Artificial Intelligence Applications in Computer Engineering.

Lipton, Z. C. (2016). The mythos of model interpretability. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.03490.

Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2009). Artificial Intelligence: A modern approach.

Vogl, R. (2017). In M. Hartung, M.-M. Bues, & G. Halbleib (Eds.), Digitalisierung des Rechtsmarkts: C. H. Beck.

Wachter, S., Mittelstadt, B., & Floridi, L. (2017). Why a right to explanation of automated decision-making does not exist in the general data protection regulation. International Data Privacy Law, 7(2), 76–99.

Waltl, B., Bonczek, G., Scepankova, E., Landthaler, J., & Matthes, F. (2017). Predicting the Outcome of Appeal Decisions in Germany’s Tax Law. 89–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64322-9_8

Waltl, B., Landthaler, J., Scepankova, E., Matthes, F., Geiger, T., Stocker, C., & Schneider, C. (2017). Automated Extraction of Semantic Information from German Legal Documents. Jusletter IT, Conference Proceedings IRIS 2017.

- 1 https://www.oracle.com/applications/oracle-policy-automation/index.html (all websites last accessed on 12 January 2018).

- 2 Not too long ago the AI winter was a consequence of the highly raised expectations that could not be met by technology. AI winter is a metaphor and describes a period of reduced funding and interest in AI. The period includes a lack of trust in AI technology due to broken promises and only partially fulfilled expectations.

- 3 https://spark.apache.org/mllib/.

- 4 http://scikit-learn.org/stable/.

- 5 https://deeplearning4j.org/.

- 6 Unless no random variables are used within the classification process.

- 7 https://hbr.org/2017/04/creating-simple-rules-for-complex-decisions.

- 8 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/20/upshot/algorithms-bail-criminal-justice-system.html.

- 9 This is strongly emphasized within Article 21 and 22 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679) have been interpreted to provide for a «right to explanation» with regard to algorithmic decision-making that affects an individual. «The data subject shall have the right not to be subject to a decision based solely on automated processing, including profiling, […].» and «[…] obtain an explanation of the decision reached after such assessment and to challenge the decision.» There is an ongoing debate around the meaning of this rule and to this date there does not seem to be an agreement on the potential consequences of this rule, and how it should be implemented. Some commentators call Article 21 «toothless» and raise important questions regarding this new right (Wachter, Mittelstadt, & Floridi, 2017).

- 10 Feasibility study on discrimination in ADM, to be published in 2018 by Gesellschaft für Informatik.

- 11 Technically deductive logic based approaches are mostly implemented with rule-based systems and do belong to the class of machine learning based approaches.

- 12 An excellent observation has been made by Goodman & Flaxman (2016): «Machine learning depends upon data that has been collected from society, and to the extent that society contains inequality, exclusion or other traces of discrimination, so too will the data.»

- 13 Support Vector Machine.

- 14 In that field, modern classification systems for images are mainly built on so-called trained neural networks, which are viewed as the classifiers that are in every dimension the least transparent and the most difficult to explain. Hendricks showed that even state-of-the-art neural network classifiers can be modified to provide a visual explanation for the classification of images and their content (Hendricks et al., 2016). A visual explanation contains both explanations for a concrete image (which correspond to our category of transparency of classification) as well as for a class (corresponding to our category for transparency of the model). Hendricks» article provides a good example of the technologies that can be leveraged to enhance explainability of so-called «deep models», which are considered difficult to interpret.