1.

Introduction ^

Design patterns are re-usable forms of a solution to a commonly occurring problem [Haapio/Passera forthcoming]. The original idea of patterns stems from Alexander [1977], who collected re-usable architecture and design solutions for other architects. From the «physical» world, the idea was later applied to digital architectures and gained widespread acceptance with Gamma et al. [1995]. Since then, design patterns have been extensively used in various fields, i.e. computer science, interface design, information systems, biology, etc. Patterns offer the benefits to: 1) identify best practices and set standards on efficient solutions for a given problem; 2) expunge the «Babel» of technical languages, by providing a problem-based syntax to people working in different domains [Haapio/Hagan 2016].

Not surprisingly, design patterns have assumed a crucial role in legal design as well. Legal design is an interdisciplinary approach that applies human-centered design to prevent or solve legal problems. By providing concrete, replicable, systematized, and extensible solutions, patterns can support the concrete implementation of abstract legal principles and make their rationale effective in the real word [Ducato, Rossana/Haapio, Helena/Hagan, Margaret/Palmirani, Monica/Passera, Stefania/Rossi, Arianna, 2018]. Over the last few years, several legal design patterns have emerged from practice – however, they have not met widespread adoption. One possible explanation is the lack of standardisation of legal design patterns, which are scattered among heterogeneous sources and libraries. As a consequence, it is often difficult to identify the right pattern, retrieve it and apply it to one’s case at hand.

To overcome this problem, based on our previous research on contract design patterns [Haapio/Hagan 2016] and privacy design patterns [Haapio et al. 2018], in this paper we propose a legal design patterns language, i.e. a system of rules for the expression of patterns in a structured way. The goal is to create coherence across the different solutions and resources, by improving their usability through examples and contextual explanations. Patterns can be used to solve a variety of different legal issues (e.g. prototyping for policy, implementing the principles of data protection by design and data protection by default, etc.). As a lab for testing our «prototype» of pattern language, in this preliminary contribution we will take as a case study information design patterns, i.e. patterns that aim to improve the communication and understanding of legal information. From a legal theory point of view, such patterns support the implementation of the principle of transparency. The latter is the backbone of European consumer and data protection law: pre-contractual information and privacy notices must be provided to consumers and data subjects in an intelligible way, meaning that the recipient of the communication must be able to find, read and understand the information without legal advice [Micklitz/Reich/Rott 2009]. Such patterns can also be usefully adopted in other contexts, for example in business-to-business contracts to minimize the risk of misunderstandings and controversies.

To this end, in Section 2 we seek coherence among different legal design patterns to solve information design issues in two different domains, namely contracts and data protection. In Section 3 we propose a patterns syntax, i.e. a structure that accommodates the most relevant elements to describe the patterns. In Section 4, we provide a brief literature overview about existing hurdles to effective privacy communication, while in Section 5 we describe design patterns that can offer solutions to such hurdles. Finally, in Section 6, future research steps are laid down.

2.

Achieving Coherence across Contract Design and Privacy Design Pattern Libraries ^

Many of the communication problems are similar in different contexts, and so are the solutions. Our analysis indicates that while some patterns are context-specific, many are universal. Some patterns work in an online environment (e.g. layering by hyperlinking or chat bots), while others work both online and offline (e.g. layering, Q&A headings, various visual pattern categories). The challenges of the people preparing Terms of Service or other consumer-facing terms are very similar to the challenges faced by the people preparing privacy policies: the audience consists of individuals who are most often reluctant to read and seldom have a chance to negotiate. The challenges of those preparing Data Processing Agreements between processors and controllers, again, are to some extent similar, but in other respects, they resemble those encountered by commercial contract drafters. The regulatory environment may require some mandatory provisions to be included, but (apart from the DPA space and some others), in commercial contracting, the freedom of contract prevails, and the parties can «make their own law» through their contract.

In commercial contracting, the problems of template writers are different from those drafting bespoke contracts. In the latter context, the challenges are often about the parties’ roles and responsibilities, aligning expectations, making the scope and goals clear, and other deal-specific issues, rather than purely legal issues. The latter might include dealing with the choice of law and dispute resolution mechanisms or default rules, basic assumptions that will apply unless expressly excluded. Related to these, patterns that help solve complex communication challenges will help. The key challenges in commercial contracting relate to the number of people involved in preparing, making, implementing and monitoring the contracts and the multitude of the parties obligations.

The contexts in which different patterns work vary, and so do their audiences. To be useful, patterns should be written with their intended audience in mind. Contracts and related design patterns, for example, are not about legal information alone, and they should take into account the different professions that may be involved in preparing the contract documents. We could call them drafters, crafters or designers, but call them writers here. Readers’ (or non-readers’) problems are at the same time also writers’ problems. When responding to the problems of the former, the patterns at the same time respond to the problems of the latter. Design-minded writers seek to make life easier for the users of their work products. In commercial contracting, the writer may be a lawyer or a contracts or commercial professional, the contract users are often business managers and negotiators who do not have a law degree: approvers, operational or delivery team members, accountants, and so on – busy and business-savvy people, only occasionally a regulator or a judge.

3.

Coherence on the Internal Structure of the Legal Design Patterns ^

Design patterns are valuable resources for practitioners and researchers only if their description is thorough, but also generic enough that they can be implemented in multiple ways. Although many different formats to describe a certain pattern exist, a classical pattern structure describes solutions to problems in a specific context alongside with the expected (positive and negative) consequences of the implementation of such solutions [Meszaros/Doble 1997]. In this light, patterns are defined as «useful techniques in terms of the functional problem they aim to solve» [Waller et al. 2016, p. 20]. Goals correspond to the manner how the pattern intends to solve the problem on a general level. To facilitate the adoption of the patterns, concrete examples of pattern use and summarizing overviews may also be provided. In our case study, each pattern has a name and presents the following structure:

- Summary: this element defines the pattern.

- Problem: this element lists the existing problem(s) that the pattern aims to solve.

- Solution: this element describes how the pattern can solve the problem.

- Goals: this element lists the goal(s) the pattern intends to achieve, in response to the problem(s).

- Constraints and consequences: these elements describe restrictions, conditions and expected outcomes for the implementation of the pattern.

- Examples: this element lists a few well-implemented occurrences of the pattern.

For example, the syntax of the pattern named «example text» in the context of privacy communication reads as follows:

- Summary: Provide an understandable example to clarify legal-technical terms or to make abstract concepts more tangible.

- Problem: Language complexity; lack of tailoring to the intended audience; vagueness of terms; lack of familiarity.

- Solution: Illustrative examples help users to transform abstract or unfamiliar legal information into more concrete experiences, that they might have lived or that they can easily imagine. They also provide practical instances of general categories and can be tailored to the intended audience of a certain service.

- Goals: Offer information in an intelligible manner; offer meaningful information to the specific user; explain in exact terms what abstract or complex notions mean in practice; make the user more knowledgeable (e.g. about data practices)

- Constraints and consequences: The choice of examples must be relevant to the intended audience. Socio-demographics characteristics of the service’s users (e.g. age) or the context (e.g. the type of service provided) can be leveraged, while the example’s efficacy should be tested with the intended audience itself. Naming one example of a class must not hide other practices (i.e. framing effect): for instance, it is unfair to exclusively mention privacy-friendly privacy practices, while omitting the risky ones

- Examples: «The personal data and any information you provide us with [...] will be used, among other purposes, to: [...] send transactional email, e.g. send you an email when you have successfully earned a Course Certificate with a copy of your Certificate».1

4.

Common Hurdles to Effective Legal Communication ^

Given the fact that hurdles to effective communication of pre-contractual and privacy notices have been extensively documented in the literature and considered the drive to innovation promoted by the GDPR’s transparency obligation, we plan on expanding the current Privacy Design Pattern library2 [Haapio et al. 2018] alongside a compilation of the hurdles to effective legal communication identified in previous research, with the aim of providing workable solutions for legal professionals. Among the hurdles, we have identified the following:

Illegibility due to small print: Small font size and lack of sufficient line spacing discourage or weary readers See Belgian Commission on Unfair Terms, 2015; Article 29 WP 2018.

Language complexity: The language of legal communication can be highly technical and complex. Therefore, it is difficult for the recipient to understand it without a legal advice. See Fabian et al. 2017; Jensen/Potts 2004; Obar/Oeldorf-Hirsch 2018; Robinson et al. 2009.

Vagueness of terms: The language of legal communication is open to multiple interpretation, due to an extensive use of vague terms such as «might», «may», «reasonable effort», that can leave the reader puzzled about their intended meaning. See Pollach, 2005; Reidenberg et al., 2016.

Wall of text: Legal documents can be displayed as impenetrable texts, small-print, without any information architecture (e.g. paragraphs, headlines, attention to size fonts), thus hindering navigation and information-finding. See Haapio et al. 2018; EDPS 2015; Passera 2015.

Excessive length: The text of legal documents is usually very long and causes information overload. See Calo 2011; Fabian et al. 2017; Obar/Oeldorf-Hirsch 2018.

Lack of audience-tailoring: Much legal communication is standardized and not designed with the intended audience in mind. See Article 29 WP 2018; Haapio et al. 2018; Robinson et al. 2009.

Wrong timing: Privacy notices and contractual information are mostly presented at the time of registration to a service or of data collection. This causes hindrance to the primary task carried out by the individual or impossibility to inform her actions (e.g. decisions about her privacy settings) because too distant in time. See Obar/Oeldorf-Hirsch 2018; Schaub et al. 2015.

Lack of familiarity: Individuals lack necessary experience and knowledge to understand, assess and use legal information. See Ben-Shahar/Schneider 2011; Solove 2013.

Inaccessibility for visually impaired users: in some cases, the format in which the legal information is incorporated is not accessible to screen reader software. See Helberger, 2013.

Scattered information: Information concerning different legal aspects about the use of the same service is scattered around a variety of legal documents (i.e. privacy policies, terms and conditions, licenses, etc.), making it hard for the user to find the specific provisions applicable to her case. See Noto la Diega 2016.

Habituation to helplessness: Users are used to be presented with an onslaught of notices that they cannot manage individually. Thus, they might experience up-front discouragement that hinders their desire to engage with the reading.

Difficult comparability: There is no standard manner to present information across legal documents of different services e.g. different privacy policies. See McDonald & Cranor 2008; Kelley et al. 2009.

As a result of the combination of these obstacles, individuals dot not fully comprehend – or disregard in toto – legal information contained in privacy policies, terms and conditions, end user agreements and similar legal documents. However, we argue that the non-readership problem [Ben-Shahar/Schneider 2011] problem can be solved, at least partially, with the help of legal design patterns or of a combination of patterns.

5.

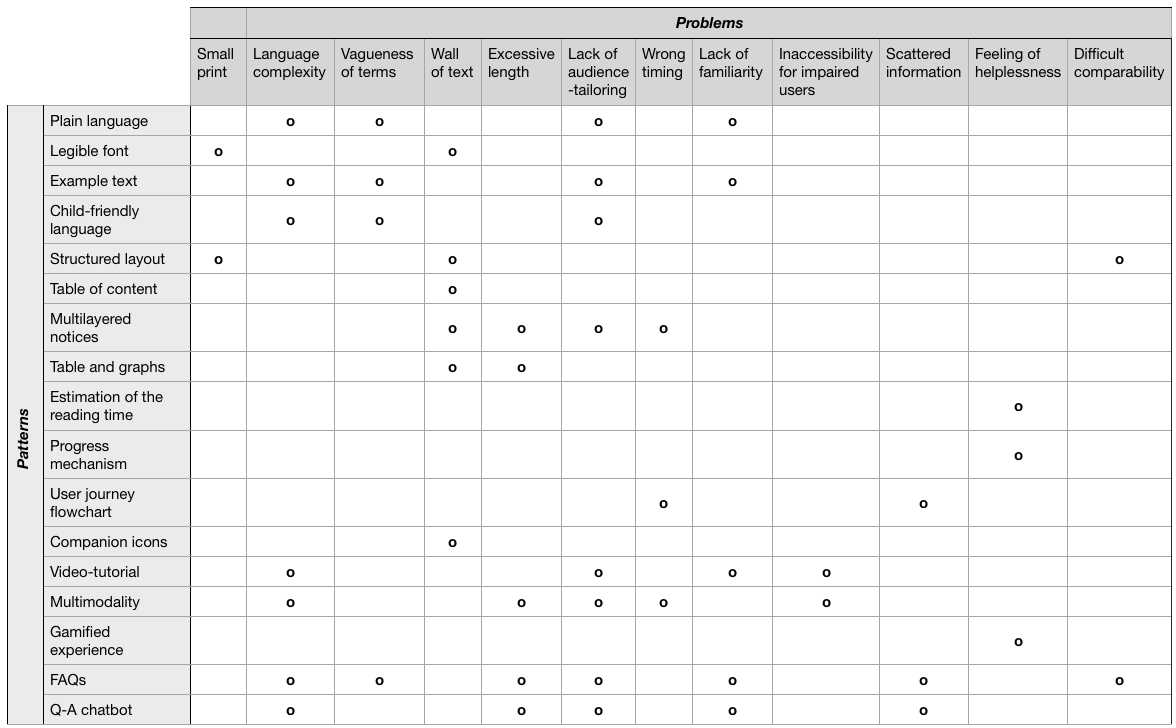

An Expanded Collection of Legal Design Patterns ^

We have surveyed existing design patterns existing on websites and mapped them to the problems and solutions described in the previous section, not necessarily in a one-to-one correspondence (see Table 1). Rather, the solution to a problem can be attained by more than one pattern or by a combination of them. Our collection for addressing the obstacles in the reading and understanding of the contractual quagmire is composed of 17 design patterns. A short summary thereof is provided in the following:

Plain language: Use clear and intelligible language that make the information easily comprehensible to anyone, especially laypeople [Article 29 WP 2018].

Legible font: use legible font in terms of size, style and weight, highlight in bold key passages and headings [Helberger 2013; Hillman 2005; Sunstein 2011].

Example text: Provide an understandable example to clarify legal-technical terms or to make abstract concepts more tangible [Waller et al. 2016].

Child-friendly language: Design a child-tailored legal document if you offer services to under-aged users [Article 29 WP 2018].

Structured layout: Organize the document in a consistent layout, where each topic is covered in a specific, labelled section [Article 29 WP 2018].

Table of contents: Place a navigable menu at the beginning of the page, where each item offers quick navigation to the corresponding section in the privacy policy or other artefact.

Multi-layered notices: The information is distributed on different layers, where the first layer provides an overview of the document, while more details are contained in the additional layers, that can also be explored at request [Article 29 WP 2018; Helberger 2013; Article 29 WP 2004].

Table and graphs: structure complex and long information in tables or graphs [Helberger 2013].

Estimation of the reading time: display of the expected duration of the reading time of the document [Elshout et al. 2016].

Progress mechanism: Display a mechanism showing the progress of the user through the various sections of the legal terms.

User journey flowchart: Identify the user’s key moments of interaction with the service and provide relevant and contextual information when the user needs it [Ofcom 2013; Sibony/Helleringer 2015].

Companion icons: Icons accompany the legal terms and visually suggest where a specific piece of information in the long text can be found [Article 12.7, GDPR; Rossi, forthcoming; Haapio/Passera, forthcoming].

Video-tutorial: The main points of the document are communicated through a video.

Multimodality: Legal information is conveyed through multiple channels, e.g. auditory (a video) and visual (written terms).

Gamified experience: Present the legal terms in a gamified environment.

FAQs: Provide easy-to-consult simplified explanation about the most frequently asked questions or about the most relevant topics of the document.

Question-answering chatbot: Exploration of the legal document in a personalized and interactive way through a conversation with a chatbot.

It must be noted that some of the proposed design patterns have not been implemented extensively in actual use or they have not undergone rigorous evaluation. The proposed classification can be therefore subject to change, as more evidence on the actual use and efficacy of the patterns is gathered. Only in-use design patterns have been surveyed, while we encourage practitioners and academics to provide their own research and attempts to enrich the collection with innovative solutions to the documented problems or to adopt and experiment the patterns more extensively. Moreover, only those patterns that can be implemented by the writer of the communication have been presented, whereas in the future we will also survey third party solutions such as rating systems [Noto La Diega 2016; Ducato 2018], dashboards, peer-to-peer platforms, and AI-powered visual summaries.

Table 1 showing the problem(s) that each pattern can potentially solve. Based on Rossi, forthcoming

6.

Future Work to Improve the Navigation through Classification Labels ^

A major shortcoming of the existing privacy design pattern libraries is the lack of categorization of the patterns. The provision of classification labels to each pattern allows for user-friendly navigation of the pattern library and facilitates the user’s search and retrieval, which should ultimately also stimulate discovery and more widespread adoption of the patterns. Our analysis has identified several dimensions of categorization. Most importantly, navigation by problem(s) and by solution(s) must be ensured, given the definition of a pattern as a useful technique in terms of the functional problem it aims to solve (see Section 3). Modality concerns the manner how the information is provided [Schaub et al. 2015] and, in addition to text-based, it can be visual, auditory, or machine-readable. The hereby described classification also adds a fourth dimension, the interactive one, if some kind of human-machine interaction is required (e.g. with the chatbot), and distinguishes between (mainly) verbal (e.g. transparent language) and (mainly) non-verbal (e.g. icons) inside of the visual category. Lastly, the library can be navigable also through tags, free-text search, or the legal reference, for example if the approach is suggested in an EU directive or regulation or in opinions or guidelines issued by official bodies (e.g. European Data Protection Board, Supervisory Authorities, etc.). This also allows to distinguish patterns that are more suitable for the privacy domain from those that are more appropriate in other contexts. Such classification and navigation mechanism will be implemented and tested in the future steps of our research. It will also be investigated if it is possible to organize the design patterns in a taxonomy that distributes them hierarchically.

7.

Conclusion ^

This paper has expanded and attempted to harmonize coherently our previous work on contract design patterns and privacy design patterns, with particular attention to legal information design, i.e., patterns that aim to improve the communication and comprehension of legal information. We have focused on online legal information that users of digital services encounter on a daily basis, such as privacy and contractual information (i.e. privacy policies, terms and conditions, etc.). Based on a review of the literature on the current shortcomings, we have proposed a list of commonly occurring hurdles to effective legal communication. We have then examined in-use design patterns that can offer a solution to such hurdles. Their effectiveness must be carefully gauged, since innovation in the design of legal communication is still in its infancy. Lastly, we have proposed some classification labels that aim at improving the navigation of existing design pattern libraries. These, taken together, can pave the way to a legal design pattern language and to more actionable pattern libraries, leading to documenting and sharing good legal information design practices across disciplines.

8.

References ^

Alexander, Christopher/Ishikawa, Sara/Silverstein, Murray/Jacobson, Max/Fiksdahl-King, Ingrid/Angel, Shlomo, A Pattern Language – Towns, Buildings, Construction, Oxford University Press, New York 1977.

Article 29 Working Party, Opinion10/2004 on More Harmonised Information Provision, November 2004.

Article 29 Working Party, Guidelines on Transparency under Regulation 2016/679, 17/ENWP260, April 2018.

Belgian Commission on Unfair Terms, Avis sur les conditions generales des sites de reseaux sociaux, 16 december 2015.

Ben-Shahar, Omri/Schneider, Carl, The failure of mandated disclosure. University of Pennsylvania Law Review, vol. 159, 2011, p. 647–749.

Calo, Ryan, Against notice skepticism in privacy (and elsewhere), Notre Dame Law Review, vol. 87, 2011, p. 1027–1072.

Ducato, Rossana, House of Terms: Fixing the Information Paradigm with Legal Design. Poster presentation at BILETA Conference 2018 «Digital Futures: places and people, technology and data», University of Aberdeen, 10–11 April 2018.

Ducato, Rossana/Haapio, Helena/Hagan, Margaret/Palmirani, Monica/Passera, Stefania/Rossi, Arianna, The Legal Design Manifesto v.1, 2018, https://www.legaldesignalliance.org (accessed on 18 December 2018).

Elshout, Maartje/Elsen, Millie/Leenheer, Jorna/Loos, Marco/Luzak, Joasia, Study on consumers» attitudes towards Terms and Conditions (T&Cs). Final report, 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/consumers-attitudes-terms-and-conditions-tcs_en.

European Data Protection Supervisor, Opinion 4/2015 Towards a New Digital Ethics, 2015.

Fabian, Benjamin/Ermakova, Tatiana/Lentz, Tino, Large-scale readability analysis of privacy policies, in: Proceedings of the International Conference on Web Intelligence, ACM, New York 2017, p. 18–25.

Gamma, Erich/Helm, Richard/Johnson, Ralph/Vlissides, John, Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software, Pearson Education India, 1995.

Haapio, Helena/Hagan, Margaret/Palmirani, Monica/Rossi, Arianna, Legal Design Patterns for Privacy, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter/Borges, Georg (Eds.), Networks, Data Protection / Legal Tech Proceedings of the 19th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2016, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG / books@ocg.at, Wien 2018, p. 445–450

Haapio, Helena/Hagan, Margaret, Design Patterns for Contracts, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/ Hötzendorfer, Walter/Borges, Georg (Eds.), Networks, Proceedings of the 19th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2016, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG / books@ocg.at, Wien 2016, p. 381–388.

Haapio, Helena/Passera, Stefania, Contracts as Interfaces: Exploring Visual Representation Patterns In Contract Design, in: Katz, Daniel Martin/Bommarito, Michael/Dolin, Ron (Eds.), Legal Informatics. Cambridge University Press, forthcoming.

Helberger, Natali, Forms matter: Informing consumers effectively (Study commissioned by BEUC), 2013.

Jensen, Carlos/Potts, Colin, Privacy policies as decision-making tools: an evaluation of online privacy notices, in: Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, New York 2004, p. 471–478.

Kelley, Patrick G./Bresee, Joanna/Cranor, Lorrie F./Reeder, Robert W., A «Nutrition Label» for Privacy, in: Proceedings of the 5th Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security SOUPS 2009, Mountain View, CA.

Mantelero, Alessandro, The future of consumer data protection in the EU. Re-thinking the «notice and consent» paradigm in the new era of predictive analytics, Computer Law & Security Review, vol. 30, no. 6, 2014, p. 643–660.

Mcdonald, Aleecia M./Cranor, Lorrie Faith, The cost of reading privacy policies, I/S: A Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, vol. 4, no. 3, 2008, p. 543–568.

Meszaros, Doble J./Doble, Jim G., A pattern language for pattern writing, in: Proceedings of International Conference on Pattern Languages of Program Design, Vol. 101, 1997, p. 529–574.

Micklitz, Hans-Wolfgang/Reich, Norbert/Rott, Peter, Understanding EU Consumer Law, 2009.

Noto La Diega, Guido, Uber law and awareness by design, An empirical study on online platforms and dehumanized negotiations, Revue Européenne de droit de la consummation/European Journal of Consumer Law, 2016 (II).

Obar, Jonathan A./Oeldorf-Hirsch, Anne, The biggest lie on the internet: Ignoring the privacy policies and terms of service policies of social networking services, Information, Communication & Society, 2018, p. 1–20.

Ofcom, A Review of Consumer Information Remedies, 2013, https://www.ofcom.org.uk/research-and-data/multi-sector-research/general-communications/consumer-information-remedies.

Passera, Stefania, Beyond the wall of text: How information design can make contracts user-friendly, in: Marcus, A. (Ed.), Design, User Experience, and Usability: Users and Interactions, vol. 9187, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Springer, Cham 2015, p. 341–352.

Pollach, Irene, A typology of communicative strategies in online privacy policies: Ethics, power and informed consent. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 62, no. 3, 2005, p. 221–235.

Reidenberg, Joel R./Bhatia, Jaspreet/Breaux, Travis D./Norton, Thomas B., Ambiguity in privacy policies and the impact of regulation, The Journal of Legal Studies, vol. 45, no. S2, 2016, p. S163–S190.

Robison, Neil/Graux, Hans/Botterman Maarten/Valeri, Lorenzo, Review of the European Data Protection Directive (sponsored by the ICO), RAND Europe, 2009.

Rossi, Arianna, Legal Design for the General Data Protection Regulation, A Methodology for the Visualization and Communication of Legal Concepts, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Dottorato di Ricerca in Law, Science and Technology, 30 Ciclo, Forthcoming.

Schaub, Florian/Balebako, Rebecca/Durity, Adam/Cranor, Lorrie, A., Design Space for Effective Privacy Notices, in: Proceedings of Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security SOUPS 2015, Ottawa.

Sibony, Anne-Lise/Helleringer, Geneviève, EU Consumer Protection and Behavioural Sciences: Revolution or Reform?, in: Alemanno A, Sibony A-L (eds.), Nudge and the Law, A European Perspective. Hart Publishing, 2015, p. 209–233.

Solove, Daniel J., Privacy Self-Management and the Consent Dilemma, Harvard Law Review, vol. 126, 2013, p. 1880–1903.

Waller, Rob/Waller, Jenny/Haapio, Helena/Crag, Gary/Morrisseau, Sandi, Cooperation through Clarity: Designing Simplified Contracts, Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation, vol. 2, no. 1–2, March/June 2016, p. 48–68.

- 1 Original example from the Interaction Design Foundation’s privacy policy https://www.interaction-design.org/about/privacy?utm_source=newsletter&utm_medium=email&utm_content=letter2018-05-24&utm_campaign=all (Accessed on June 29, 2018).

- 2 http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/legal-design-pattern-libraries/privacy-design-pattern-library/; for the Contract Design Pattern Library, see http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/legal-design-pattern-libraries/contracts/ and Know Your Rights Pattern Library http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/kyr/#1.