1.

The Challenge of Communicating Complex Legal Information ^

The challenge is familiar from many contexts: how to translate complex legal information into simple-to-follow, actionable, motivating instructions for the people who are impacted or are expected to comply. Even if the information is provided in the plainest language possible, if people do not read it, how can they be expected to know the contents or comply?

Legal information appears in many different contexts and forms. Contracts are the most commonplace, but perhaps the worst offender: they have often been accused to be written «by lawyers for lawyers».1 In recent years, on several continents, researchers and practitioners have started to explore new ways of making and representing contracts.2 Apart from contracts, new genres and designs have been presented in privacy communication3 and other contexts where complex legal information should be more accessible and actionable.4

In communicating legal information and guidance for business people, a tension exists among legal-friendly, business-friendly, and user-friendly approaches.5 A balance needs to be found between functionality and precision, and between precision and ease of use. In our previous work, we have sought to find those balances by bringing a proactive approach and design thinking into the world of contracting and law,6 exploring various information design approaches.7 Examples of these initiatives have been presented at previous IRIS events and in the related proceedings.8

This paper introduces Legal Design to respond to the challenge of communicating complex legal information. It proposes a new mindset, shifting lawyers from being unconscious designers – creating contracts, notices, policies, and manuals in conventional ways – to conscious designers, with a focus on the users and the need for more useful and usable guidance and more creative and ambitious ideas.9 With this new mindset, it becomes natural to look for new tools to present legal products and information in more engaging and actionable ways. Playbooks offer an especially promising new option to be added to lawyers» genres of communication.

2.

Legal Design: An Emerging Way to Respond to the Challenge ^

Legal Design is an umbrella term for merging forward-looking legal thinking with design thinking. It is an interdisciplinary approach to apply human-centered design to prevent or solve legal problems. It prioritizes the point of view of «users» of the law – not only lawyers and judges, but also citizens, consumers, and businesses. Its point of departure is that the people who use legal information, documents, services, and policies are not being served well by current designs.10

One of the very first known users of the concept Legal Design is Colette R. Brunschwig, whose doctoral dissertation in 2001 had the concept as its subtitle: Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen – Legal Design.11 The concept was later used by Stefania Passera in the context of Legal Design Jam events, a by-product of her doctoral dissertation.12 The first Legal Design Jam event was organized in 2013 at the University of Aegean, followed by one at Stanford and another in San Francisco, hosted by Margaret Hagan. At these events, the goal was for lawyers, designers, policy-makers, and students to work together to transform complex legal information – in the latter two events, the Wikimedia Trademark Policy.13

The concept gained more popularity, especially in social media, with the Legal Design Summit in Helsinki in 2016 and 2017.14 The Legal Design Alliance (LeDA) was launched in 2018, with the Legal Design Manifesto at its core,15 at the Legal Design Geek event in London16. Seeking to build a bridge between practitioners and scholars working in this emerging field, LeDA organized the workshop Legal Design as Academic Discipline17 in connection with the JURIX Conference in Groningen in December 2018.

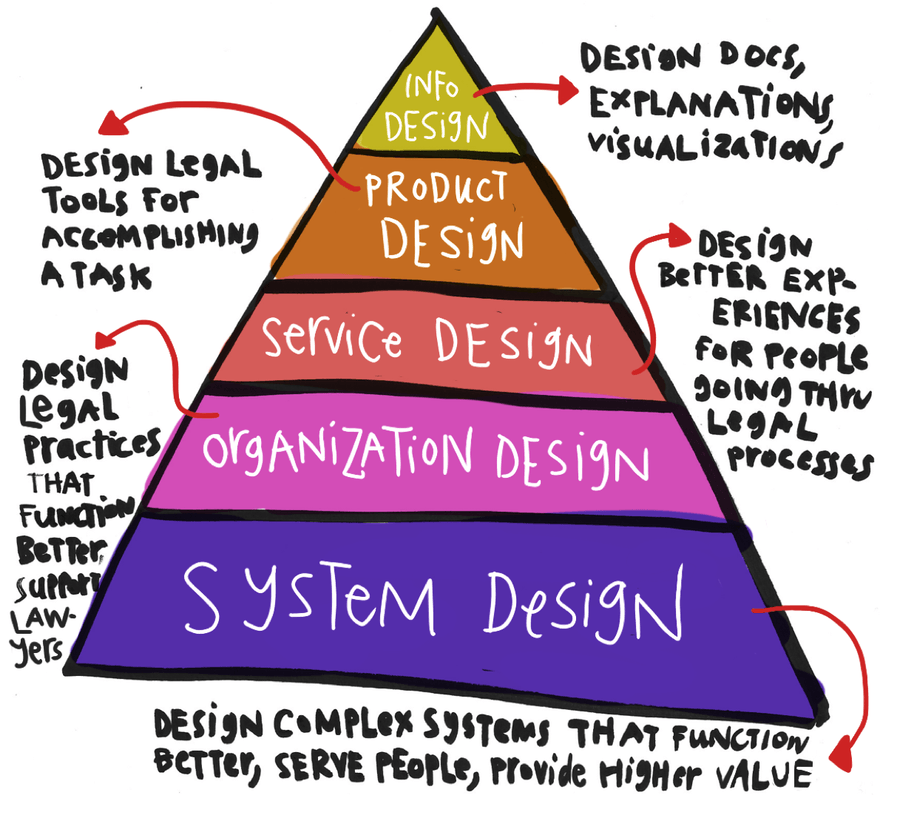

Legal Design takes an interdisciplinary and proactive approach to law, covering not only legal information and documents, but also legal products, services, practices, processes, systems, and tools.18 These can include bots, apps, and various other solutions, and lead to redesigned privacy notices, consent procedures, and terms of service, for example. The different branches of Legal Design have been depicted in the following pyramid figure by Margaret Hagan, one of the founders of LeDA:

Figure 1: The Many Different Branches of Legal Design19

© Margaret Hagan. Used with permission.

In this paper, the focus is on the top of the pyramid in Figure 1, namely the design of legal products, in general, and legal information, in particular. Legal information design is about organizing and displaying information in a way that maximizes its clarity and understandability for the intended users.

With the help of Legal Design, it becomes natural to move from text-only guidance to supplementing text with visualizations – for example, flowcharts, maps, timelines, or explanatory diagrams. In the context of legal manuals and guides, visualization can help create functional, useful, and usable instructions with step-by-step guidance. It can help people to think, communicate, make assumptions visible, and secure understanding across disciplines. The goal is not just to create images – the goal is to create understanding.

Examples of corporate compliance and contracting guidance available on the Internet seem to rely heavily on conventional text-only communication.20 They look and feel like legal documents. This paper posits that they could benefit greatly from Legal Design and the playbook approach.

3.

The Genre of Playbooks: A Promising Way for Lawyers to Engage Reluctant Readers ^

Playbooks are not new. Team sports players have had playbooks for a long time, and so have film and theater actors. In football, for example, a dictionary definition of a playbook is «a notebook containing descriptions of all the plays and strategies used by a team, often accompanied by diagrams, issued to players for them to study and memorize before the season begins»21. Playbooks have recently made their way to several business book titles, too. As the name «playbook» indicates, the genre seeks to distance itself from conventional paper guidebooks and even e-books, introducing a different way to communicate the contents in an engaging way that resonates with the intended audience.

In recent years, playbooks have started to appear in a number of contexts, varying from business strategy and marketing to public sector innovation, supply chain management, and product or service design. In business, the playbooks often contain business process workflows aimed at ensuring a consistent response to situations commonly encountered during the operation of the business.22 In the public sector, playbooks have emerged as a means to guide action within innovation initiatives and digital services transformations.23 In many fields, both in the private and in the public sector, playbooks have become part of everyday vocabulary. Today, a Google search for «strategy playbook» brings more than 30,000 results.

Playbooks have made their way to the corporate legal world through corporate functional needs, for example mergers and acquisitions24 and corporate compliance and contracting guidance.25 A contracting playbook can be used to enable people, non-lawyers or lawyers, to make choices and understand what to do at the different stages of the lifecycle of a contract, with little or no training or oversight from the legal department. It can contain tools and templates that help people do what they are expected to do. A contract playbook can cover many types of contracts or be tailored to just one contract type. It can provide access to standard templates and preferred clauses and texts, including acceptable fallback provisions and recommended processes for obtaining approval for signing. It can document processes and workflows, identify key stakeholders and their authority to sign, and state related escalation and approval requirements. In this way, it can be used to guide the drafting, negotiation, and review of contracts, explain regulatory requirements or internal policies, and help identify and control contract and legal risk. Seeing the process view, the workflow, and everyone’s tasks makes it easier for people to comply and understand why it is important.

Despite their growing use in practice, playbooks have so far gained little attention in research.26 One of the reasons may be that not many playbooks are available on the Internet. Among even those examples, it is obvious that playbooks, too, can suffer from lack of good design, with the resulting reluctance of people to read them. Many seem to be heavily text-based, with occasional tables full of small print.27

The emerging Legal Design Pattern Libraries28 provide one possible way to change things for the better. Visual design patterns can be relied on to organize and display information in a way that maximizes clarity and understandability. Adding examples, plain language translations, audio, or video, and digitizing the outcome – merging Legal Tech with Legal Design – can facilitate better guidance: people can then find the information they need, understand what they find, and use what they find to meet their needs.

Different playbooks, toolkits, and patterns can be pitched at different levels of expertise, and serve different purposes: some might be for problem-solving, others for sense-making. There is no one-size-fits all solution. In future, Legal Design Pattern Libraries could serve as repositories and links to other good playbook patterns, helping people find inspiration and examples. Developing a Legal Design Pattern Language and a related Library Navigator to help users search and find suitable patterns is part of the research and development agenda of LeDA.29

The time has come to move from static text-only guidebooks to visual, engaging playbooks. Whether paper-based or digital, these can pave the way for legal guidance that people will actually want to read and use. New labeling and fresh design can change perceptions and awaken interest among people who are otherwise reluctant to read anything that resembles legal writing.

4.

What the Future Will Hold ^

If someone is reluctant to read a document, labeling it as «legal information» or «a compliance manual» is not going to help. Naming it «a playbook» instead might. A new name may initiate a new way of approaching and presenting legal information, with a focus on what the users prefer and removing what currently prevents them from reading. Even though significant, labeling is just a small first step, with many other issues to tackle. This paper argues that Legal Design and the emerging work around legal design patterns can make it easier to engage those issues. In the process, lawyers can transform from being unconscious designers to conscious designers.

Playbooks offer a promising new option for lawyers» genres of communication. Apart from the contexts addressed here, playbooks hold potential in legal education, innovation initiatives, digital services transformations, and wherever trusting relationships are important.30 Existing technology can help transform static, text-only pdf or MS Word guidebooks to interactive and collaborative playbooks that help generate more accessible, understandable, useful, and usable legal products. In their digital form, interactive playbooks can be integrated with new decision support technology, document automation and assembly tools, machine learning, and AI/augmented drafting services,31 offering these the opportunity to develop into true game-changers, for the benefit of lawyers and clients alike.

5.

References ^

Barton, Thomas D./Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde/Haapio, Helena, Contracting for Innovation and Innovating Contracts: An Overview and Introduction to the Special Issue, Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation, Vol. 2, No. 1–2, March/June 2016, p. 3–9.

Beamex, Contract Playbook – Best Practices for Negotiating, Concluding and Escalating Certain Contracts for Legal Review at Beamex, https://lakius.fi/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Beamex-Contracts-Playbook.pdf (all websites last accessed on 23 January 2019).

Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde/Barton, Thomas D./Haapio, Helena, From Visualization to Legal Design: A Collaborative and Creative Process, American Business Law Journal, Vol. 54, No. 2, 2017, p. 347–392.

Berger-Walliser, Gerlinde/Bird, Robert C./Haapio, Helena, Promoting Business Success through Contract Visualization, The Journal of Law, Business & Ethics, Vol. 17, Winter 2011, p. 55–75.

Brunschwig, Colette R., Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen – legal design (Doctoral dissertation), Zürcher Studien zur Rechtsgeschichte, vol. 45. Rechtswissenschaftliche Fakultät d. Universität Zürich, Schulthess Juristische Medien, Zurich 2001.

Conboy, Kevin, Diagramming Transactions: Some Modest Proposals and a Few Suggested Rules, Transactions: Tennessee Journal of Business Law, Vol. 16, 2014, p. 91–108.

Dictionary.com, Playbook, https://www.dictionary.com/browse/playbook.

Forsström, Pirjo-Leena/Haapio, Helena/Passera, Stefania, FAIR Design Jam: A Case Study on Co-Creating Communication about FAIR Data Principles, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter/Sorge, Christoph (Eds.), Trends and Communities of Legal Informatics. Proceedings of the 20th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2017, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft / books@ocg.at, Wien 2017, pp. 433–440.

Greater Than Experience/Data Transparency Lab, Designing for Trust: The Data Transparency Playbook, Second Edition, 2018.

Haapio, Helena, Next Generation Contracts: A Paradigm Shift. Lexpert Ltd, Helsinki 2013.

Haapio, Helena/Barton, Thomas D., Business-Friendly Contracting: How Simplification and Visualization Can Help Bring It to Practice, in: Jacob, Kaj/Schindler Dierk/Strathausen Roger (Eds.), Liquid Legal, Management for Professionals, Springer, Cham 2017, p. 371–396.

Haapio, Helena/de Rooy, Robert/Barton, Thomas D., New Contract Genres, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Saarenpää, Ahti/Schafer, Burkhard (Eds.), Data Protection / LegalTech, Proceedings of the 21th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2018, Editions Weblaw, Bern 2018, pp. 455–460.

Haapio, Helena/Hagan, Margaret/Palmirani, Monica/Rossi, Arianna, Legal Design Patterns for Privacy, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Saarenpää, Ahti/Schafer, Burkhard (Eds.), Data Protection/LegalTech. Proceedings of the 21th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2018, Editions Weblaw, Bern 2018, pp. 445–450.

Haapio, Helena/Plewe, Daniela Alina/de Rooy, Robert, Next Generation Deal Design: Comics and Visual Platforms for Contracting, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter/Borges, Georg (Eds.), Networks. Proceedings of the 19th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2016, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG / books@ocg.at, Wien 2016, p. 373–380.

Haapio, Helena/Plewe, Daniela Alina/de Rooy, Robert, Contract Continuum: From Text to Images, Comics, and Code, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter/Sorge, Christoph (Eds.), Trends and Communities of Legal Informatics. Proceedings of the 20th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2017, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft / books@ocg.at, Wien 2017, p. 411–418.

Hagan, Margaret, Law by Design, http://www.lawbydesign.co.

Hagan, Margaret, 5 Insights from a Legal Design Jam, The Whiteboard, 24 October 2013, Stanford University’s Institute of Design (d.school), http://whiteboard.stanford.edu/blog/2013/10/25/5-insights-from-a-legal-design-jam.

Hagan, Margaret, Making Legal Design a Thing – and an Academic Discipline, Legal Design and Innovation Blog, 14 December 2018, https://medium.com/legal-design-and-innovation/making-legal-design-a-thing-and-an-academic-discipline-5a7e57fa43e8.

Hricic, David/Morgan, Asya-Lorrene S./Williams, Kyle H., Ethics of Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Drafting Legal Documents, Texas A&M Journal of Property Law Volume 4 2018, p. 484.

Humbert, X. Paul/Mastice, Robert C., The Playbook Methodology, The European Financial Review, 22 June 2015, http://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/?p=4566.

Keating, Adrian/Baasch Andersen, Camilla, A Graphic Contract: Taking Visualization Contracting A Step Further, Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation, Vol. 2, Issue 1–2, March/June 2016, p. 10–18.

Lauritsen, Marc, Transform your contracting playbook into a negotiation game changer, Contracting Excellence Journal 25 May 2016, https://journal.iaccm.com/contracting-excellence-journal/iaccm-member-articles/turn-your-contracting-playbook-into-a-negotiation-game-changer.

Lauritsen, Marc, Enhancing Contract Playbooks with Interactive Intelligence – Part I. The Journal of Robotics, Artificial Intelligence & Law, Volume 1, No. 5. September–October 2018(a), p. 327–340, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/571acb59e707ebff3074f461/t/5b534e620e2e72a1709f06c2/1532186211546/Enhancing+Contract+Playbooks+with+Interactive+Intelligence%E2%80%94Part+I.pdf.

Lauritsen, Marc, Enhancing Contract Playbooks with Interactive Intelligence – Part II. The Journal of Robotics, Artificial Intelligence & Law, Volume 1, No. 6. November-December 2018(b), p. 385–401.

Legal Design Alliance (LeDA), https://www.legaldesignalliance.org.

Miller, Sterling, Ten Things: Creating a Good Contract Playbook…, Blog post, 17 July 2018, https://sterlingmiller2014.wordpress.com/2018/07/17/ten-things-creating-a-good-contract-playbook/.

Passera, Stefania, Beyond the Wall of Contract Text – Visualizing Contracts to Foster Understanding and Collaboration Within and Across Organizations, Doctoral Dissertation, Aalto University 2017.

Passera, Stefania/Haapio, Helena/ Curtotti, Michael, Making the Meaning of Contracts Visible – Automating Contract Visualization, in: Schweighofer, Erich/Kummer, Franz/Hötzendorfer, Walter (Eds.), Transparency, Proceedings of the 17th International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2014, Österreichische Computer Gesellschaft OCG, Wien 2014, p. 443–450.

Plewe, Daniela Alina/de Rooy, Robert, Integrative Deal-design – Cascading from Goal-hierarchies to Negotiations and Contracting, Journal of Strategic Contracting and Negotiation, Vol. 2, No. 1–2, March/June 2016, p. 19–33.

Rossi, Arianna/Ducato, Rossana/Haapio, Helena/Passera, Stefania/Palmirani, Monica, Legal Design Patterns: Towards a New Language for Legal Information Design, in: Proceedings of the 22nd International Legal Informatics Symposium IRIS 2019.

- 1 See, e.g., Berger-Walliser/Bird/Haapio 2011 (emphasis added).

- 2 See, generally, Berger-Walliser/Bird/Haapio 2011; plewe/de rooy 2016; Keating/Baasch Andersen 2016; Haapio 2013; Conboy 2014; Haapio/Barton 2017; Passera 2017; Barton/Berger-Walliser/Haapio 2016; Haapio/De Rooy/Barton 2018; see also Contract Design Pattern Library at http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/legal-design-pattern-libraries/contracts/ (all websites last accessed on 23 January 2019).

- 3 See, generally, Haapio/Hagan/ Palmirani/Rossi 2018; see also Privacy Design Pattern Library at http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/legal-design-pattern-libraries/privacy-design-pattern-library; Greater Than Experience/Data Transparency Lab 2018.

- 4 Margaret Hagan, the Director of the Legal Design Lab at Stanford Law School, has collected different models to present complex legal information, see Examples of Legal Communication Designs at http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design and, generally, Hagan (n.d.); see also Legal Design Pattern Libraries at http://www.legaltechdesign.com/communication-design/legal-design-pattern-libraries.

- 5 In the context of contracts and contracting guidance, see, e.g., Haapio/Barton 2017; Passera 2017.

- 6 See, generally, Berger-Walliser/Barton/Haapio 2017; Haapio/Barton 2017.

- 7 Haapio 2013; Haapio/Plewe/de Rooy 2016 and 2017; Plewe/de Rooy 2016.

- 8 See, e.g., Passera/Haapio/Curtotti 2014 and the IRIS conference papers mentioned in the previous footnotes.

- 9 Similarly Hagan (n.d.), Introduction.

- 10 Legal Design Alliance (n.d.).

- 11 Brunschwig 2001.

- 12 See http://legaldesignjam.com; Passera 2017.

- 13 See Hagan 2013; Forsström/Haapio/Passera 2017.

- 14 See https://www.legaldesignsummit.com.

- 15 Legal Design Alliance (n.d.).

- 16 See https://www.legalgeek.co/legaldesign.

- 17 See http://gdprbydesign.cirsfid.unibo.it/legaldesign-workshop; Hagan 2018.

- 18 Legal Design Alliance (n.d.); Hagan (n.d.).

- 19 Hagan (n.d.), Section 1.

- 20 See, e.g., examples listed in Miller 2018 and the following Section.

- 21 Dictionary.com (n.d.). In the context of theater, the same source defines a playbook as «the script of a play, used by the actors as an acting text» and «a book containing the scripts of one or more plays».

- 22 For a general introduction to the playbook methodology, see Humbert/Mastice 2015; for samples of a project management playbook and tools, see https://www.demandmetric.com/content/project-management-playbook; see also https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Playbook.

- 23 For samples of playbooks in the public innovation space, see https://oecd-opsi.org/?s=playbook; see also https://oecd-opsi.org/have-we-reached-peak-toolkit/; Digital Services Playbook, https://playbook.cio.gov/, stating the reasons of having a playbook: «[t)oday, too many of our digital services projects do not work well, are delivered late, or are over budget. To increase the success rate of these projects, the U.S. Government needs a new approach. We created a playbook of 13 key ‹plays› drawn from successful practices from the private sector and government that, if followed together, will help government build effective digital services.»

- 24 See Midaxo M&A playbooks available at https://www.midaxo.com/playbooks.

- 25 See Miller 2018; Lauritsen 2016, 2018(a) and 2018(b).

- 26 Sterling Miller’s and Marc Lauritsen’s work on contract playbooks provides a rare exception. See footnote above.

- 27 See Sample Agreement Playbook shown and sample playbook listed under Resources in Miller 2018. More user-friendly examples include the Beamex Contract Playbook, see Beamex (n.d.).

- 28 See links to the Contract Design Pattern Library, Privacy Design Pattern Library, and Legal Communication Library in footnotes 2–4; see also Rossi et al. 2019.

- 29 Ongoing work around creating a Pattern Language for Legal Design has been reported in Rossi et al. 2019.

- 30 Greater Than Experience/Data Transparency Lab 2018.

- 31 See Lauritsen 2018(a) and 2018(b); for augmented drafting services, see also Hricic/Morgan/Williams 2018.