1.1.

Vox Iurisprudentiae Picturae ^

- We live in an increasingly visual culture and are exposed to evergrowing quantities of pictures, images, icons, charts, figures, graphs, scales, tables, diagrams, maps, sketches, blueprints, and colorful and animated graphics. […] As new electronic tools promote the graphical, will new energies be focused on both understanding and creating through visual means? Will an increasingly visual culture devote more attention to the visual and teach about it just as print culture recognized that reading and writing text were fundamental skills that should occupy fundamental positions in the curriculum? Can the new media narrow the gulf between «visual reading» and «visual writing,» between visual consuming and visual creating, in the same manner that print narrowed the gulf between textual reading and writing? Is it likely that the new technologies can effect a new balance between visual consumer and visual creator? And if this occurs, what impact will it have on a text-oriented enterprise such as law?3

1.2.

Beyond Verbocentrism: Law as a Not Exclusively Textual Phenomenon ^

1.3.

Questions ^

2.1.1.1.

High Visual Legal Culture: Visual Legal Art ^

Fig. 1. Gabriël Metsu, The Triumph of Justice11

- The relationship between law and art can be analytically distinguished into two components: law’s art, the ways in which political and legal systems have shaped, used, and regulated images and art, and art’s law, the representation of law, justice, and other legal themes in art.12

2.1.1.2.

Popular Visual Legal Culture ^

2.1.2.

Further Visual Legally Relevant Contents ^

2.2.1.

Legal Visualizations in Legislation and in the Legal Sources in a Strict Sense ^

Images have a shadowy existence in modern law. Legal texts—whether laws, judgements or learned documents—on the whole contain no images or graphics. Text-books without images are almost symbolic of the subject of law. Although even here—as in all things in life—the exceptions prove the rule. The Highway Code with its images of traffic signals is the most obvious example. And in the fields of invention, patent and brand ownership, law images are not just normal, they are indispensable.25

2.2.2.

Legal Visualizations in Court Judgments ^

In recent years, the media have expected courts to inform the general public about proceedings and rulings. In response, some courts have resorted to public relations activities such as establishing designated websites and issuing media bulletins.39 Along with such verbal legal communication, I could well imagine courts also practicing visual legal communication (visual court PR). Thus, visual court PR would intersect with e-justice (2.2.4.1).

2.2.3.

Visual Jurisprudence: Legal Visualizations in Legal Education and Research ^

2.2.3.1.

Legal Visualizations in Legal Education ^

2.2.3.2.

Legal Visualizations in Legal Research ^

2.2.4.1.

Legal Visualizations in State Legal Practice in a Wide Sense ^

2.2.4.2.

Legal Visualizations in Private Legal Practice ^

- As a way to introduce the possibilities of approaching the law visually, this Comment employs the metaphor of legal map-making. A legal map is a mediation device between the law and a client’s needs to make a decision, a tool to be used by lawyers acting as legal guides. As travelers use maps of a physical landscape to decide the best way to go, lawyers create and use maps of the legal landscape to counsel clients on the best way to go.67

- As discussed earlier, electronic contracts eventually will be more than paper contracts in electronic form. They will monitor performances and alert parties and their lawyers about problems with performance or about a need for modifying and agreement due to changing conditions. […] What is important to recognize in connection with visual communication is that the medium’s visual capabilities provide intriguing possibilities for alerting us about change and about the direction of change. Images and numbers can be employed to show change in ways that are not possible with print. […] In the contract context, for example, lack of performance might send a red flag to the attorney for one of the parties. This could be an actual image of a red flag, and the red flag, if ignored, could grow larger over time, something that would be both meaningful and attention getting.73

Haapio et al. suggest introducing «[v]isualization [t]echniques into the [c]ontracting [p]rocess.»74 Haapio in particular has explored contract visualization in many other publications.75 So far, the examples of legal visualizations in private legal practice do not have a legal basis, but legislators will provide them with such a basis in the future.

2.2.5.

Visualized Legal and Legally Relevant Facts ^

- Today, with increasing frequency video displays and digital images accompany lawyers’ opening statements and closing arguments at trial. They are introduced as evidence in the form of animations, digital re-enactments, and video documentaries showing tort victims living damaged lives in the wake of accidents or botched surgeries or exposure to defective products or chemical pollutants. […]. And increasingly, on appeal, judges review the visual record of the trial to assess allegations of error. Did jurors, or perhaps a lower appellate judge, unreasonably construe visual evidence that jurors saw at trial? […] Lawyers show digital animations depicting reconstructed airplane accidents or that take us inside the body, picturing, for example, how plaque in an artery of the heart was allegedly dislodged by a careless surgeon or a faulty medical instrument.86

3.1.

Findings ^

3.2.

Conclusions ^

3.3.

Outlook ^

4.

References ^

Asimow, Michael & Mader, Shannon, Law and Popular Culture: A Coursebook (New York, NY, et al.: Peter Lang, 2007).

Aktolga, Elif, Ros, Irene, & Assogba, Yannick, «Detecting Outlier Sections in US Congressional Legislation,» Proceeding SIGIR '11 Proceedings of the 34th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, eds. Ricardo Baeza-Yates et al. (New York, NY: ACM, 2011), 235–244, available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2009951&CFID=179985020&CFTOKEN=83482624 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Assogba, Yannick, Ros, Irene, & McKeon, Matt, «DocBlocks: Communication-minded Visualization of Topics in U.S. Congressional Bills,» Proceedings CHI EA «10 CHI «10 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, eds. Elisabeth Mynatt & Don Schoner (New York, NY: ACM, 2010), 4117–4122, available at: http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1754112 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Austin, Regina, «The Next ‹New Wave›: Law-Genre Documentaries, Lawyering in Support of the Creative Process, and Visual Legal Advocacy,» Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J., Vol. 16, Issue 3 (2006), 809–868.

Bainbridge, Jason, «Visual Law: The Changing Signifiers of Law in Popular Visual Culture,» Prospects of Legal Semiotics, eds. Anne Wagner & Jan M. Broekman (Dordrecht et al.: Springer, 2010), 193–215.

Baumann, Max, «Weg vom Text oder: Plädoyer für einen breiteren Weg vom Text zum Verstehen,» Recht vermitteln, Strukturen, Formen und Medien der Kommunikation im Recht, ed. Kent D. Lerch, Die Sprache des Rechts, Studien der interdisziplinären Arbeitsgruppe Sprache des Rechts der Berlin-Brandenburgischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vol. 3, ed. Kent D. Lerch (Berlin, New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 2005), 1–22.

Bergmans, Bernhard, Visualisierung in Rechtslehre und Rechtswissenschaft: Ein Beitrag zur Rechtsvisualisierung (Berlin: Logos Verlag, 2009).

Berti, Stephen, Einführung in die schweizerische Zivilprozessordnung (Basel: Helbing Lichtenhahn, 2011).

Bodenmann, Guy, Verhaltenstherapie mit Paaren: Ein modernes Handbuch für die psychologische Beratung und Behandlung (Bern et al.: Verlag Hans Huber, 2004).

Boehme-Nessler, Volker, Unscharfes Recht: Überlegungen zur Relativierung des Rechts in der digitalisierten Welt (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2008).

Id., «Die Öffentlichkeit als Richter? Chancen und Risiken von Litigation-PR aus verfassungsrechtlicher und rechtssoziologischer Sicht,» Die Öffentlichkeit als Richter?, ed. Volker Boehme-Nessler (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2010), 20–51.

Id., Pictorial Law: Modern Law and the Power of Pictures (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2011).

Bradford, William C., «Reaching the Visual Learner: Teaching Property Through Art,» The Law Teacher, Vol. 12, No. 1, 12–13, available at:

http://lawteaching.org/lawteacher/2004fall/lawteacher2004fall.pdf (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Brunschwig, Colette R., Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen: Legal Design, PhD thesis University of Zurich (Zurich: Schulthess Juristische Medien, 2001).

Id., «Legal Design: ein Bilderbuch für den Rechtsunterricht,» Rechtsgeschichte und Interdisziplinarität: Festschrift für Clausdieter Schott zum 65. Geburtstag, eds. Marcel Senn & Claudio Soliva (Bern et al.: Peter Lang, 2001), 361–371.

Id., «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung: Gesprächs- und Entwicklungspotenziale,» Zur Geschichte des Rechts: Festschrift für Gernot Kocher zum 65. Geburtstag, eds. Markus Steppan & Helmut Gebhardt (Graz: Leykam, 2006/2007), 39–47.

Id., «Rechtsvisualisierung: Skizze eines nahezu unbekannten Feldes,» Zeitschrift für Informations-, Telekommunikations- und Medienrecht (MultiMedia und Recht MMR), No. 1, (2009), IX–XII, available at: http://rsw.beck.de/cms/main?sessionid=F4DA148B2A2F488EADC31B7816208320

&docid=272992&docClass=NEWS&site=MMR&from=mmr.10 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Id., «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics: A Comparison of How these Legal Disciplines Relate to Visual Law,» Structuring Legal Semantics: Festschrift for Erich Schweighofer, eds. Anton Geist et al. (Bern: Editions Weblaw, 2011), 573–667, also available at: http://jusletter-eu.weblaw.ch/magnoliaPublic/issues/2011/104/article_324.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Id., «Multisensory Law and Therapeutic Jurisprudence: How Family Mediators Can Better Communicate with Their Clients,» Phoenix Law Review, Vol. 5, No. 4 (2012), 705–746.

Id., Law Is Not or Must Not Be Just Verbal and Visual in the 21st Century: Toward Multisensory Law,» Nordic Yearbook of Legal Informatics 2010–2012, eds. Dan Jerker B. Svantesson & Stanley Greenstein (Stockholm: Ex Tuto Publishing, 2013), 231–283.

Burgess, David, «Reflections on the Use of Visual Representations of Legal Representations of Legal and Institutional Constructs as Assignments in Legal Education for Pre-Service Teachers in Canada,» Argumentation 2011: International Conference on Alternative Methods of Argumentation in Law, Conference Proceedings, eds. Michał Araszkiewicz et al. (Brno: Masaryk University, 2011), 123–166.

Curtotti, Michael & McCreath, Eric, «Enhancing the Visualization of Law,» October 2, 2012, 1–27, available at: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2160614 and http://cs.anu.edu.au/people/Eric.McCreath/papers/visualizationCurtottiMccreath2012.pdf (both websites last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Del Mar, Maksymilian, «Legal Understanding and the Affective Imagination,» Affect and Legal Education: Emotion in Learning and Teaching the Law, eds. Paul Maharg & Caroline Maughan (Farnham, Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011), 177–191.

Douzinas, Costas & Nead, Lynda, «Introduction,» Law and the Image, eds. Costas Douzinas and Lynda Nead (Chicago, IL, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 1–15.

Douzinas, Costas, «Prosopon and Antiprosopon: Prolegomena for a Legal Iconology,» Law and the Image, eds. Costas Douzinas and Lynda Nead (Chicago, IL, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 36–67.

Dudek, Michał, «Paternalistic Regulations Expressed through Means of Visual Communication of Law? Contribution to Another Distinction of Paternalistic Legal Regulations,» Argumentation 2011: International Conference on Alternative Methods of Argumentation in Law, Conference Proceedings, eds. Michał Araszkiewicz et al. (Brno: Masaryk University, 2011), 167–179.

Engels, Jens Ivo, «Zum historischen Quellenwert von Bildern: Das Beispiel des Sachsenspiegels,» Funktion und Form: Quellen- und Methodenprobleme der mittelalterlichen Rechtsgeschichte, eds. Karl Kroeschell & Albrecht Cordes (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1996), 153–184.

Feigenson, Neal, «Audiovisual Communication and Therapeutic Jurisprudence: Cognitive and Social Psychological Dimensions,» International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, Vol. 33 (2010), 336–340.

Id., «Visual Evidence,» Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, Vol. 17, No. 2 (2010), 149–154.

Feigenson, Neal & Dunn, Meghan A., «New Visual Technologies in Court: Directions for Research,» Law and Human Behavior, Vol. 27, No. 1 (2003), 109–126.

Feigenson, Neal & Spiesel, Christina, Law on Display: The Transformation of Legal Persuasion and Judgment (New York, NY, London: New York University Press, 2009).

Fill, Hans-Georg, «Polysyntactic Meta Modelling: Historical Roots in the Work of Raimundus Lullus,» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 439–443.

Franca Filho, Marcílio Toscano, A Cegueira da Justiça (Porto Alegre: Fabris, 2011).

Garnitschnig, Karl & Lachmayer, Friedrich, Computergraphik und Rechtsdidaktik (Vienna: Manzsche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung, 1979).

Garrett, Meghann L., «Trademarks as a System of Signs: A Semiotician’s Look at Trademark Law,» The Semiotics of Law in Legal Education, eds. Jan M. Broekman & Francis J. Mootz III (Dordrecht et al.: Springer, 2010), 221–236.

Gross, Karen, «Visual Imagery and Law Teaching,» The Law Teacher, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1999), 8, also available at: http://lawteaching.org/lawteacher/1999fall/visualimagery.php (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Haapio, Helena, «Visualising Contracts and Legal Rules for Greater Clearity,» The Law Teacher, Vol. 44, No. 3 (2010), 391–394.

Haapio, Helena et al., «Time for a Visual Turn in Contracting?» Journal of Contract Management, Summer (2012), 49–57.

Id., «Contract Clarity and Usability through Visualization,» Knowledge Visualization Currents: From Text to Art to Culture, eds. Francis T. Marchese & Ebad Banissi (London et al.: Springer, 2013), 63–84.

Id., «Designing Readable Contracts: Goodbye to Legal Writing – Welcome to Information Design and Visualization,» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 445–452.

Hahn, Tamara, Mielke, Bettina, & Wolff, Christian, «Juristischen Lehrcomics: Anforderungen und Möglichkeiten,» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 393–402.

Heddier, Marcel & Knackstedt, Ralf, «Empirische Evaluation von Rechtsvisualisierungen am Beispiel von Handyverträgen,» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 413–420.

Henze, Raphaela, Bildmedien im juristischen Unterricht (Berlin: Tenea Verlag, 2003).

Herzog, Felix, Strafrecht illustrated: 30 Fälle aus dem Strafrecht in Wort und Bild (Hamburg: merus verlag, 2007).

Hilgendorf, Erich, dtv-Atlas Recht, Vol. 1, Grundlagen, Staatsrecht, Strafrecht (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2003).

Id., dtv-Atlas Recht, Vol. 2, Verwaltungsrecht, Zivilrecht (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2007).

Hohmann, Jutta & Morawe, Doris, Praxis der Familienmediation: Typische Probleme mit Fallbeispielen und Formularen bei Trennung und Scheidung, Munich: Centrale für Mediation, 2001.

Holzer, Florian, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht: Ein Beitrag zur Steuerung der visuellen Rechtskommunikation, PhD thesis University of Wurzburg (Wurzburg: [not published], 2011), available from the author.

Holzinger, Stephan & Wolff, Uwe, Im Namen der Öffentlichkeit: Litigation-PR als strategisches Instrument bei juristischen Auseinandersetzungen (Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2009).

Hudson-Smith, Andrew, Evans, Stephen, & Batty, Michael, «Building the Virtual City: Public Participation Through E-Democracy,» Knowledge, Technology & Policy, Vol. 18, No. 1 (2005), 62–85, available at: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs12130-005-1016-9?LI=true (last accessed July 22, 2013).

Jay, Martin, «Must Justice Be Blind? The Challenge of Images to the Law,» Law and the Image, eds. Costas Douzinas and Lynda Nead (Chicago, IL, London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 19–35.

Jones III, Henry W (Hank), «Envisioning Visual Contracting: Why Non-Textual Tools Will Improve Your Contracting,» Contracting Excellence, Vol. 2, No. 6 (2009), 27–31.

Jordan Bennett, Stephanie, «Paternalistic Manipulation through Pictorial Warnings: The First Amendment, Commercial Speech, and the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act,» Miss. L.J., Vol. 81, No. 7 (2012), 1909–1940.

Joseph, Gregory P., Modern Visual Evidence (New York, NY: Law Journal Press, 2011).

Katsh, Ethan M., Law in a Digital World (New York, NY, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Knackstedt, Ralf & Heddier, Marcel, «Argumentationstheoriebasierte Visualisierung als ‹Double-Feature, ›» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 429–438.

Kocher, Gernot, Zeichen und Symbole des Rechts: Eine historische Ikonographie (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 1992).

Id., «Die Rechtsikonographie,» Die Wolfenbütteler Bilderhandschrift des Sachsenspiegels: Aufsätze und Untersuchungen, Kommentarband zur Faksimileausgabe, ed. Ruth Schmidt-Wiegand (Berlin: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt, 1993), 107–117.

Id., «Iconography of Law: Presentation of the Project ‹Bilddokumentation zur Rechtsgeschichte, ›» Jahrbuch der Oswald von Wokenstein Gesellschaft, Vol. 11, eds. Sieglinde Hartmann & Ulrich Müller (Frankfurt am Main: Reichert[?], 1999), 143–151.

Lachmayer, Friedrich, «Graphische Darstellungen im Rechtsunterricht,» Zeitschrift für Verkehrsrecht, Heft 8 (1976), 230–234.

Id., «Visualisierung des Rechts,» Zeichenkonstitution, Akten des 2. Semiotischen Kolloquiums Regensburg 1978, Vol. 2 (Berlin, New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 1981), 208–212.

Langer, Thomas, Die Verbildlichung der juristischen Ausbildungsliteratur (Berlin: Tenea Verlag, 2004).

Lerner, Ralph E. & Bresler, Judith, Art Law, 4th ed. (New York, NY: Practicing Law Institute, 2013).

Leuenberger, Christoph & Uffer-Tobler, Beatrice, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht (Bern: Stämpfli Verlag, 2010).

Loukis, Euripidis, Xenakis, Alexandros, & Tseperli, Nektaria, «Using Argument Visualization to Enhance e-Participation in the Legislation Formation Process,» Electronic Participation: First International Conference, ePart 2009, Linz, Austria, September 2009, Proceedings, eds. Anne Macintosh & Efthimios Tambouris (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2009), 125–138.

Lück, Heiner, «Rechtssymbolik,» Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, Vol. 24 Quadriburigum – Rind, eds. Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, & Heiko Steuer, 2nd, completely revised ed. (Berlin, New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 2003), 284–291.

McCloskey, Matthew J., «Visualizing the Law: Methods for Mapping the Legal Landscape and Drawing Analogies,» Wash. L. Rev., Vol. 73 (1998), 163–191.

Maier, Nadine, Litigation PR: Medienarbeit in juristischen Auseinandersetzungen (Hamburg: Diplomica, 2012).

Mauet, Thomas A., Trial Techniques, 8th ed. (Austin, TX, et al.: Wolters Kluwer, 2010).

Mauet, Thomas A. & Wolfson, Warren D., Trial Evidence, 5th ed. (Austin, TX, et al.: Wolters Kluwer, 2012).

Meier, Isaak, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht: Eine kritische Darstellung aus der Sicht von Praxis und Lehre (Zürich, Basel, Genf: Schulthess Juristische Medien, 2010).

Mnookin, Jennifer L., «The Image of Truth: Photographic Evidence and the Power of Analogy,» Yale J.L. & Human, Vol. 10, 1–74.

Olbrich, Sebastian & Simon, Carlo, «Process Modelling towards E-Government: Visualisation of process-like legal regulations,» Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on e-Government (ECEG 2007), ed. Dan Remenyi (Den Haag: Academic Conferences & Publishing International, 2007), 405–414, available online at http://www.academic-conferences.org/eceg/eceg2007/2-proceedings-eceg07.htm (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Parycek, Peter, Sachs, Michael, & Schossböck, Judith, «Offene Daten und Informationen im Politikzyklus: Voraussetzungen, Risiken und Umsetzungspotenziale von Open Government und Open Data in europäischer Perspektive,» Europäische Projektkultur als Beitrag zur Rationalisierung des Rechts: Tagungsband des 14. Internationalen Rechtsinformatik-Symposions IRIS 2011, eds. Erich Schweighofer & Franz Kummer (Wien: Oesterreichische Computer Gesellschaft, 2011), 335–339, available online at: http://jusletter-eu.weblaw.ch/service/search.html?queryStr=peter+parycek (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Petschenig, Michael, Der kleine Stowasser: Lateinisch-deutsches Schulwörterbuch (Zurich: Orell Füssli Verlag, 1971).

Rehbinder, Manfred, «Litigation-PR als professionelle Dienstleistung: Zur Rechtskommunikation in der Mediengesellschaft,» Kommunikation: Festschrift für Rolf H. Weber zum 60. Geburtstag, eds. Rolf Sethe et al. (Bern: Stämpfli, 2011), 771–780.

Riedl, Reinhard, «Die Kompetenz zur Abstraktion als Informatik-Erfolgsfaktor,» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 35–45.

Robinson, Peter, «Graphic and Symbolic Representation of Law: Lessons from Cross-Disciplinary Research,» eLaw Journal: Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law, Vol. 16, No. 1 (2009), 53–83, available online at: http://elaw.murdoch.edu.au/index.php/elawmurdoch/article/view/5 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Röhl, Klaus F., «Gerechtigkeit vor Augen: Visuelle Kommunikation im Gerechtigkeitsdiskurs,» Kriterien der Gerechtigkeit: Festschrift für Christofer Frey zum 65. Geburtstag, eds. Peter Dabrock et al. (Gütersloh: Güthersloher Verlagshaus, 2003), 369–384.

Id., «Logische Bilder im Recht,» Organisation und Verfahren im sozialen Rechtsstaat: Festschrift für Friedrich E. Schnapp zum 70. Geburtstag, eds. Hermann Butzer, Markus Kaltenborn, & Wolfgang Meyer (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2008), 815–838.

Id., «(Juristisches) Wissen über Bilder vermitteln,» Wissen in (Inter-)Aktion: Verfahren der Wissensgenerierung in unterschiedlichen Praxisfeldern, eds. Ulrich Dausendschön-Gay, Christine Domke, & Sören Ohlhus (Berlin, New York, NY: Walter de Gruyter, 2010), 281–311.

Röhl, Klaus F. & Röhl, C., Allgemeine Rechtslehre, 3rd ed. (Cologne, Munich: Carl Heymanns Verlag, 2008).

Röhl, Klaus F. & Ulbrich, Stefan, Recht anschaulich: Visualisierung in der Juristenausbildung (Cologne: Halem, 2007).

Rüthers, Bernd, Fischer, Christian, & Birk, Axel, Rechtstheorie mit Juristischer Methodenlehre (Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck, 2011).

Sherwin, Richard K., When Law Goes Pop, The Vanishing Line between Law and Popular Culture (Chicago, IL, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2002).

Id., «Law in Popular Culture,» The Blackwell Companion to Law and Society, ed. Austin Sarat (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 95–112.

Id., «Imagining Law as Film (Representation without Reference?),» Law and the Humanities: An Introduction, eds. Austin Sarat, Matthew Anderson, & Catherine O. Frank (Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 241–268.

Id., Visualizing Law in the Age of the Digital Baroque: Arabesques and Entanglements (London, New York, NY: Routledge, 2011).

Id., «Visual Jurisprudence,» N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev., Vol. 57 (2012–2013), 11–39.

Silbey, Jessica, «Images in/of Law,» N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev., Vol. 57 (2012–2013), 171–183.

Spiesel, Christina O., Sherwin, Richard K., & Feigenson, Neal, «Law in the Age of Images: The Challenge of Visual Literacy,» Contemporary Issues of the Semiotics of Law: Cultural and Symbolic Analyses of Law in a Global Context, eds. Anne Wagner, Tracey Summerfield, & Farid Samir Benavides Vanegas (Oxford, Portland, OR: Hart Publishing, 2005), 231–255.

Streli, Roland, Die situative Visualisierung von Gesetzestexten am Beispiel der Strassenverkehrsordnung, PhD thesis University of Innsbruck (Innsbruck: [not published], 2008), available at: http://sowibib.uibk.ac.at/cgi-bin/xhs_voll.pl?UID=&ID=83483 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Sutter-Somm, Thomas, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht, 2nd ed. (Zurich, Basel, Geneva: Schulthess Juristische Medien, 2012).

Tobler, Christa & Beglinger, Jacques, Grundzüge des bilateralen (Wirtschafts-)Rechts Schweiz – EU: Systematische Darstellung in Text und Tafeln, Vol. 1 & 2 (Zurich, St. Gallen: Dike, 2013).

Wagner, Anne & Sherwin, Richard K. (eds.), Law, Culture, and Visual Studies (forthcoming), available at: http://www.springer.com/law/book/978-90-481-9321-9 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

Wahlgren, Peter, «Visualization of the Law,» Legal Stagings: The Visualization, Medialization and Ritualization of Law in Language, Literature, Media, Art and Architecture, eds. Kjell Å Modéer & Martin Sunnquist (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, 2012), 19–24.

Walser Kessel, Caroline, Kennst du das Recht? Ein Sachbuch für Kinder und Jugendliche (Bern: Editions Weblaw, 2011).

Id., «Rechtsvisualisierung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Abstraktion und Applikation: Am Beispiel des neuen schweizerischen Kindes- und Erwachsenenschutzrechts,» Abstraction and Application, IRIS 2013, Proceedings of the 16th International Legal Informatics Symposium, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Franz Kummer, & Walter Hötzendorfer (Vienna: Österreichische Computergesellschaft, 2013), 403–411.

Id., Im Bild sein über das Kindes- und Erwachsenenschutzrecht: Der Vorsorgeauftrag und die gesetzliche Vertretung (Bern: Editions Weblaw, 2013).

Wegscheider, Herberg, «Visualisierung im Strafrecht,» IT in Recht und Staat, Aktuelle Fragen der Rechtsinformatik 2002, eds. Erich Schweighofer, Thomas Menzel, & Günther Kreuzbauer (Vienna: Verlag Österreich, 2002), 319–327.

Colette R. Brunschwig, Senior Research Associate, Centre for Legal History, Legal Visualization Unit, Department of Law, University of Zurich, Switzerland.

I would like to extend my special thanks to Franz Kummer, co-founder and co-proprietor of Weblaw corporation (Switzerland), for inviting me to write this article. Furthermore, I wish to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Mark Kyburz for his editorial assistance.

- 1 See Petschenig, Der kleine Stowasser, 540.

- 2 On iurisprudentiam picturatam, see, for instance, Kocher, Zeichen und Symbole des Rechts, 8, and Lück, «Rechtssymbolik,» 284.

- 3 Katsh, Law in a Digital World, 154.

- 4 Id., Law in a Digital World, 146.

- 5 Feigenson & Spiesel, Law on Display, xi. See also http://lawondisplay.fromthesquare.org (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 6 Rüthers, Fischer, & Birk, Rechtstheorie mit Juristischer Methodenlehre, 99 n. 150.

- 7 Silbey, «Images in/of Law,» 177. See also Baumann, «Weg vom Text,» 22.

- 8 Sherwin, Visualizing Law in the Age of the Digital Baroque, 11. See also Feigenson & Spiesel, Law on Display, 13–17, and N. Y. L. Sch. Rev., Visualizing Law in the Digital Age, October 19 & 21, 2011, available at: http://www.nylslawreview.com/visualizing-law-in-the-digital-age (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 9 Non-legal disciplines also study visual legal communication practices, albeit only partially and marginally. One case in point is business informatics; see, for instance, Olbrich & Simon, «Process Modelling towards E-Government,» 405–414; Fill, «Polysyntactic Meta Modelling,» 439-443; Heddier & Knackstedt, «Empirische Evaluation von Rechtsvisualisierungen am Beispiel von Handyverträgen,» 413–420, and Knackstedt & Heddier, «Argumentationstheoriebasierte Visualisierung als ‹Double-Feature, ›» 429–438.

- 10 See Legal Visualization Unit, Legal Image Database, available at: http://www.rwi.uzh.ch/oe/zrf/abtrv/bilddatenbank_en.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 11 http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7b/Gabri%C3%ABl_Metsu_008.jpg (last accessed on July 22, 2013). This picture is in public domain.

- 12 Douzinas & Nead, «Introduction,» 11.

- 13 On its symbolic value, see, for instance, ECHR – Itineris (English version), available at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=po7SltV7r4U (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 14 On legal iconography, see, for instance, Kocher, Zeichen und Symbole des Rechts, 36–41; Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 11–26; Kocher, «Die Rechtsikonographie,» 107–117, and Mike Widener, «Legal Iconography Resources,» November 10, 2010, available at: http://library.law.yale.edu/news/legal-iconography-resources (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 15 On legal iconology, see, for instance, Douzinas, «Prosopon and Antiprosopon,» 36–67, and Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 11–22.

- 16 On the art and law movement, see, for instance, Marcílio Toscano Franca Filho, A Cegueira da Justiça (Porto Alegre: Fabris, 2011), and Ralph E. Lerner & Judith Bresler, Art Law, 4th ed. (New York, NY: Practicing Law Institute, 2013).

- 17 On visual legal semiotics, see Wagner & Sherwin (eds.), Law, Culture and Visual Studies (forthcoming).

- 18 Asimow & Mader, Law and Popular Culture, 4.

- 19 See Richard K. Sherwin, When Law Goes Pop: The Vanishing Line between Law and Popular Culture (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2007).

- 20 See, for instance, Bainbridge, «Visual Law,» 193–215.

- 21 Sherwin, «Imagining Law as Film,» 246.

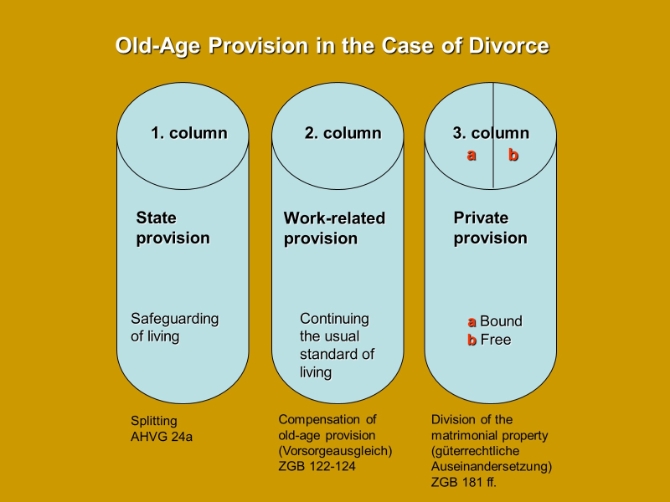

- 22 Hohmann & Morawe, Praxis der Familienmediation, 200.

- 23 Brunschwig, «Multisensory Law and Therapeutic Jurisprudence,» 718. See Bodenmann, Verhaltenstherapie mit Paaren, 36, fig. 9.

- 24 See, for instance, Loukis, Xenakis, & Tseperli, «Using Argument Visualization to Enhance e-Participation in the Legislation Formation Process,» 125–138.

- 25 Boehme-Nessler, Pictorial Law, 105. On visual traffic law, see also Roland Streli, Die situative Visualisierung von Gesetzestexten am Beispiel der Strassenverkehrsordnung, PhD thesis University of Innsbruck (Innsbruck: [not published], 2009), and Dudek, «Paternalistic Regulations Expressed through Means of Visual Communication of Law,» 167–179.

- 26 See Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 80–10 and 154–208.

- 27 See http://computationallegalstudies.com (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 28 See Daniel Martin Katz, «Measuring the Complexity of the Law: The United States Code,» October 8, 2010, available at: http://computationallegalstudies.com/2010/10/08/measuring-the-complexity-of-the-law-the-united-states-code-repost/ (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 29 Assogba, Ros, & McKeon, «DocBlocks,» 4117–4122.

- 30 Aktolga, Ros, & Assogba, «Detecting Outlier Sections in US Congressional Legislation,» 235–244.

- 31 Curtotti & McCreath, «Enhancing the Visualization of Law,» 1–27.

- 32 See, for instance, Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 23–26.

- 33 See Lachmayer, «Visualisierung des Rechts,» 208–212, and Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 56–57.

- 34 See, for instance, Wegscheider, «Visualisierung im Strafrecht,» 319–327; Röhl & Ulbrich, Recht anschaulich, 12–27, and Bergmans, Visualisierung in Rechtslehre und Rechtswissenschaft, 1 sqq.

- 35 See Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 56.

- 36 See, for instance, Boehme-Nessler, Unscharfes Recht, 225–346, esp. 232–233, and Röhl & Röhl, Allgemeine Rechtslehre, 20–23.

- 37 See, for instance, Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 80–81.

- 38 Colette R. Brunschwig, «Legal Visualizations in Court Judgments: Reflections and Questions,» June 8, 2011, available at: http://community.beck.de/gruppen/forum/visual-law/legal-visualizations-in-court-judgments-reflections-and-questions (last accessed on July 22, 2013). For further information, I refer the reader to my discussion on legal visualizations in court judgments in this English posting.

-

39

The Institut für Rechtswissenschaft und Rechtspraxis [= Institute for Jurisprudence and Legal Practice] at the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland) organized a conference on «Kommunikation der Gerichte» [= Court Communication], which was devoted to verbal court communication (see http://www.irp.unisg.ch/~/media/Internet/Content/Dateien/InstituteUndCenters/IRP/Pdf%20Tagungen/2013/

1083_Kommunikation%20der%20Gerichte.ashx; last accessed on July 22, 2013). - 40 See http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/2/220.en.pdf (last accessed on July 22, 2013). For details, see my «Producing, Analyzing, and Evaluation Legal Visualizations: A Pioneering Course at the Department of Law, University of Basel, Switzerland» (http://community.beck.de/gruppen/forum/producing-analyzing-and-evaluating-legal-visualizations-a-pioneering-course-at-the-department-of-law-unive; last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 41 Brunschwig, «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics,» 621. See also Caroline Walser Kessel, Kennst du das Recht? Ein Sachbuch für Kinder und Jugendliche (Bern: Editions Weblaw, 2011), and http://kinderbuch.weblaw.ch (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 42 Del Mar, «Legal Understanding and the Affective Imagination,» 181.

- 43 See Lachmayer, «Graphische Darstellungen im Rechtsunterricht,» 230–234; id., Computergraphik und Rechtsdidaktik, 9 sqq.; Cooper, Getting Graphic 2, 6 sqq.; Gross, «Visual Imagery and Law Teaching,» 8; Raphaela Henze, Bildmedien im juristischen Unterricht (Berlin: Tenea Verlag, 2003); Eric Hilgendorf, dtv-Atlas Recht, Vol. 1, Grundlagen, Staatsrecht, Strafrecht (München: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2003); Bradford, «Reaching the Visual Learner,» 12–13; Thomas Langer, Die Verbildlichung der juristischen Ausbildungsliteratur (Berlin: Tenea Verlag, 2004); Felix Herzog, Strafrecht illustrated: 30 Fälle aus dem Strafrecht in Wort und Bild (Hamburg: merus verlag, 2007); Erich Hilgendorf, dtv-Atlas Recht, Vol. 2, Verwaltungsrecht, Zivilrecht (Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, 2007); Klaus F. Röhl & Stefan Ulbrich, Recht anschaulich: Visualisierung in der Juristenausbildung (Cologne: Halem, 2007); Bernhard Bergmans, Visualisierungen in Rechtslehre und Rechtswissenschaft: Ein Beitrag zur Rechtsvisualisierung (Berlin: Logos Verlag, 2009); Röhl, «(Juristisches) Wissen über Bilder vermitteln,» 295–305; Burgess «Reflections on the Use of Visual Representations of Legal Representations of Legal and Institutional Constructs as Assignments in Legal Education for Pre-Service Teachers in Canada,» 123–166; Hahn, Mielke, & Wolff, «Juristische Lehrcomics,» 393–402, and Christa Tobler & Jacques Beglinger, Grundzüge des bilateralen (Wirtschafts)-Rechts Schweiz – EU: Systematische Darstellung in Text und Tafeln, Vol. 1 and 2 (Zurich, St. Gallen: Dike, 2013).

- 44 See, for instance, Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 205–211, and http://vdrl.eu/dokumentation/rechtsdidaktik-und-paedagogik/ (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 45 See http://www.irp.unisg.ch/de/Kompetenzzentrum+Rechtspsychologie (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 46 On visual justice, see, for instance, Röhl, «Gerechtigkeit vor Augen,» 369, 382–383.

- 47 See, for instance, Kocher, Zeichen und Symbole des Rechts, 7–14, and Engels, «Zum historischen Quellenwert von Bildern,» 153–184.

- 48 See, for instance, Röhl, «Logische Bilder im Recht,» 815–838.

- 49 See, for instance, Röhl, «Gerechtigkeit vor Augen,» 369–384; Röhl & Röhl, Allgemeine Rechtslehre, 20–23, and Röhl, «Logische Bilder im Recht,» 815–838.

- 50 Brunschwig, «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics,» 622: See also http://elaw.murdoch.edu.au/index.php/elawmurdoch/article/view/5 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 51 See Parycek, Sachs, & Schossböck, «Offene Daten und Informationen im Politikzyklus,» 336. On legal visualization in e-government, see also Olbrich & Simon, «Process Modelling towards E-Government,» 405–414.

- 52 See, for instance, Bundeskanzleramt, «Rechtsinformationssystem RIS,» [s. t.], available at: http://www.ris.bka.gv.at/ (last accessed on July 22, 2015).

- 53 See Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, Eidgenössisches Justiz- und Polizeidepartement, Dokumentation, «Neues Erwachsenenschutzrecht tritt am 1. Januar 2013 in Kraft: Kantone müssen ihre Behördenorganisation anpassen,» January 12, 2011, available at: http://www.ejpd.admin.ch/content/ejpd/de/home/dokumentation/mi/2011/2011-01-12.html, and http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/210/indexni45.html (both websites last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 54 See Walser Kessel, «Rechtsvisualisierung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Abstraktion und Applikation,» 403–411. See also Caroline Walser Kessel, Im Bild sein über das Kindes- und Erwachsenenschutzrecht: Der Vorsorgeauftrag und die gesetzliche Vertretung (Bern: Editions Weblaw, 2013).

- 55 See id., «Rechtsvisualisierung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Abstraktion und Applikation,» 403, 408.

- 56 See id., «Rechtsvisualisierung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Abstraktion und Applikation,» 408.

- 57 See ibid.

- 58 See The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation, Legislation, «The Protection of Adults,» in force since January 1, 2013, http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/210/indexni45.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 59 SeeThe Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation, Legislation, Representative Deputyship, «Asset Management,» in force since January 1, 2013, http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/210/a395.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013). See also Walser Kessel, «Rechtsvisualisierung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Abstraktion und Applikation,» 407.

- 60 See The Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation, Legislation, The Deputyship, «Combination of Deputyships,» in force since January 1, 2013, http://www.admin.ch/ch/e/rs/210/a397.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013). See also Walser Kessel, «Rechtsvisualisierung im Spannungsfeld zwischen Abstraktion und Applikation,» 407.

- 61 See, for instance, European Court of Human Rights, The Court, General Information on the Court, available at: http://www.echr.coe.int/ECHR/EN/Header/The+Court/Introduction/Information+documents/, and European e-justice, Visual Business Register displays commercial networks in Estonia, January 17, 2011, available at: https://e-justice.europa.eu/newsManagement.do?idNews=14&plang=fi&action=show (both websites last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 62 See http://www.parlament.hu/angol/legislation.htm (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 63 See http://www.parl.gc.ca/About/House/ReportToCanadians/2008/rtc2008_06-e.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 64 See, for instance, Parycek, Sachs, & Schossböck, «Offene Daten und Informationen im Politikzyklus,» 336.

- 65 See, for instance, European Commission (ed.), «Information and Communication Technologies: Biometrics and Justice,» RTD Info, Magazine on European Research, [s.t.], available at: http://ec.europa.eu/research/rtdinfo/46/print_article_2932_en.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 66 See, for instance, Hudson-Smith, Evans, & Batty, «Building the Virtual City,» 62–85.

- 67 McCloskey, «Visualizing the Law,» 164–165.

- 68 Id., «Visualizing the Law,» 165.

- 69 Meier, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht, 586 n. 1078.

- 70 Brunschwig, «Multisensory Law and Therapeutic Jurisprudence,» 733.

- 71 http://www.sydneymediation.com.au/ (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 72 http://www.sydneymediation.com.au/books-sydney-mediation.php, and Colette R. Brunschwig, Visual Law for Children and Adolescents, August 11, 2010, available at: http://community.beck.de/gruppen/forum/visual-law/visual-law-for-children-and-adolescents (both websites last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 73 Katsh, Law in a Digital World, 161–162.

- 74 Haapio et al., «Time for a Visual Turn in Contracting?» 52.

- 75 See, for instance, Haapio, «Visualising Contracts and Legal Rules for Greater Clearity,» 391–394; id., «Contract Clarity and Usability through Visualization,» 64–84, and id., «Designing Readable Contracts,» 445–452. See also Jones III, «Envisioning Visual Contracting,» 27–31.

- 76 Jordan Bennett, «Paternalistic Manipulation through Pictorial Warnings,» 1911.

- 77 Id., «Paternalistic Manipulation through Pictorial Warnings,» 1910.

- 78 Id., «Paternalistic Manipulation through Pictorial Warnings,» 1912.

- 79 Ibid. On these images in private legal practice, see also Markus Becker, «Raucher-Abschreckung: USA bringen Schockbilder auf Zigerettenschachteln,» Spiegel Online Wissenschaft, November 11, 2010, available at: http://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/medizin/raucher-abschreckung-usa-bringen-schockbilder-auf-zigarettenschachteln-a-728540.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 80 See Maier, Litigation PR, 31–32. On litigation PR, see also Holzinger & Wolff, Im Namen der Öffentlichkeit, 18–23; Boehme-Nessler, «Die Öffentlichkeit als Richter?» 20-51; Rehbinder, «Litigation-PR als professionelle Dienstleistung,» 771–780.

- 81 See http://www.merkur-online.de/aktuelles/boulevard/kachelmanns-richter-rudern-zurueck-967074.html. See also Maier, Litigation PR, 3, and http://www.sueddeutsche.de/leben/promi-outfits-vor-gericht-boese-maedchen-in-nadelstreifen-1.176782 (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 82 See Holzinger & Wolff, Im Namen der Öffentlichkeit, 13, and Maier, Litigation PR, 17, 20–21.

- 83 See Mnookin «The Image of Truth,» 4.

- 84 Feigenson & Spiesel, Law on Display, 1.

- 85 Sherwin, When Law Goes Pop, 6–7. Similarly, see Feigenson & Dunn, «New Visual Technologies in Court,» 109.

- 86 Sherwin, Visualizing Law in the Age of the Digital Baroque, 14. Similarly, see id., Visualizing Law in the Age of the Digital Baroque, 58–59.

- 87 Spiesel, Sherwin, & Feigenson, «Law in the Age of Images,» 232, footnote 2.

- 88 See Leuenberger & Uffer-Tobler, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht, 221–225, n. 9.28–9.43; Berti, Einführung in die schweizerische Zivilprozessordnung, 123–125, n. 369–372, and Sutter-Somm, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht, 194–196, n. 780–789. As regards US-American evidence law (federal level), see, for instance, Mauet & Wolfson, Trial Evidence, 9–26, 347–354, and Joseph, Modern Visual Evidence, Chapter 9.02.

- 89 See Leuenberger & Uffer-Tobler, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht; Berti, Einführung in die schweizerische Zivilprozessordnung, 133, n. 397–398, and Sutter-Somm, Schweizerisches Zivilprozessrecht. Regarding US-American evidence law (federal level), see, for instance, Mauet & Wolfson, Trial Evidence, 15.

- 90 See, for instance, Feigenson & Dunn, «New Visual Technologies in Court,» 109–126; Mauet, Trial Techniques, 13–29; Feigenson, «Audiovisual Communication and Therapeutic Jurisprudence,»336–340, and id., «Visual Evidence,» 149–154.

- 91 See, for instance, Spiesel, Sherwin, & Feigenson, «Law in the Age of Images,» 232, 238–255; http://www.nyls.edu/faculty/faculty_profiles/richard_k_sherwin; and (both websites last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 92 See Austin, «The Next ‹New Wave›,» 848–867, and

- 93 See, for instance, Sherwin, «Law in Popular Culture,» 95–112. See also http://www.nyls.edu/centers/projects/visual_persuasion/law_and_popular_culture/popular_legal_studies (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 94 See id. «Law in Popular Culture,» 95–112.

- 95 See, for instance, Bainbridge, «Visual Law,» 193–215, and Garrett, «Trademarks as a System of Signs,» 221–236.

- 96 Spiesel, Sherwin, & Feigenson, «Law in the Age of Images,» 247.

- 97 On visual law, see Brunschwig, «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics,» 617–628.

- 98 On the subject matter of visual law, see id., «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics,» 618–626. This paper marks a first attempt to classify or systematize the law as a visual phenomenon both within and outside the legal context. The need for classification or systematization is also recognized by SILBEY, who argues that «it might be helpful if within the field of the visualization of law we develop a taxonomy of the various strategies of visualization, how they occur in our society generally, and how they are embedded in diverse legal contexts specifically» (Silbey, «Images in/of Law,» 183).

- 99 On the cognitive interest of visual law, see id., «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics,» 626–628.

- 100 Sherwin uses the term «visual jurisprudence.» See Sherwin, Visualizing Law in the Age of the Digital Baroque, 5, 10, 13, 18, 21, 44, 49, 52, 54, 55, 122, 179, 185, 187, and 190–191, and id., «Visual Jurisprudence,» 11, 12, 20, 36–39.

- 101 Silbey, «Images in/of Law,» 179, 183. See also Wahlgren, «Visualization of the Law,» 19–24.

- 102 Brunschwig, Rechtsvisualisierung, IX–XII; Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 53–60, and Riedl, «Die Kompetenz zur Abstraktion als Informatik-Erfolgsfaktor,» 42. Grappling with the term «Rechtsvisualisierung» [«visualization of law»], Holzer instead suggests «Rechtsvisualistik» [«visualistics of law»] (see Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 55–57). The word «visualization» can be associated both with the production of legal visualizations and with the end-product—the legal visualization—itself. The same applies to the German expression «Rechtsvisualisierung» (see Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 54–55, 58).

- 103 Sherwin, «Visual Jurisprudence,» 20. See also Brunschwig, «Multisensory Law and Legal Informatics,» 607–617, and Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 55–57.

- 104 See Brunschwig, «Law Is Not or Must Not Be Just Verbal or Visual in the 21st Century,» 238.

- 105 See Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 80–99, 154–191; id., «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42, and Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 58, 128–163.

- 106 See Brunschwig, «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42.

- 107 See Silbey, «Images in/of Law,» 180.

- 108 See, for instance, Brunschwig, Visualisierung von Rechtsnormen, 118–121; id., «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42; Röhl & Ulbrich, Recht anschaulich, 53–65; Bergmans, Visualisierungen in Rechtslehre und Rechtswissenschaft, 33–88, and Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 63–106.

- 109 See, for instance, Brunschwig, «Legal Design,» 367–369, and id. «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42.

- 110 See Brunschwig, «Legal Design und Web Based Legal Training,» 297–308; Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 194–195, and Heddier & Knackstedt, «Empirische Evaluation von Rechtsvisualisierungen am Beispiel von Handyverträgen,» 413–420.

- 111 See Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 111–116.

- 112 See id., Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 106.

- 113 See Brunschwig, «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42, and Holzer, Rechtsvisualisierung im Strafrecht, 116–126.

- 114 See Brunschwig, «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42.

- 115 On the context dependency of meaning, see, for instance, Sherwin, «Visual Jurisprudence,» 16.

- 116 See Brunschwig, «Rechtsikonographie, Rechtsikonologie und Rechtsvisualisierung,» 42.

- 117 On whether Justice must be blind or not, see Jay, «Must Justice Be Blind?» 19–35.

- 118 See Sellert, Recht und Gerechtigkeit in der Kunst, 111; Röhl, «Gerechtigkeit vor Augen,» 371, and Johann von Schwarzenberg, «Bambergische Peinliche Halsgerichtsordnung,» f. 77b, available at: http://www.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/desbillons/bambi/seite164.html (last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 119 See Brunschwig, «Law Is Not or Must Not Be Just Verbal or Visual in the 21st Century,» 282 sq.

- 120 There is no space to enumerate Professor Lachmayer’s publications in full. Instead, I refer the reader to the comprehensive list of publications on his website (see http://www.legalvisualization.com/; last accessed on July 22, 2013).

- 121 See http://www.univie.ac.at/RI/IRIS2013/ (last accessed on July 22, 2013).