1.

Introduction ^

During the last two decades, terms such as «information society» and «information age» have been widely discussed. The information society’s myriad questions and specific problems can be analyzed from different perspectives of many disciplines; but some common characteristics are given as being indicators of the information society:1

- Information and knowledge are undoubtedly of paramount importance; theoretical knowledge is more than ever at the center of economic and social life.

- The information infrastructure that has been put in place to handle the information flow is in constant progress: information and communication technologies (ICT) proliferate and advance, online services expand.

- The access to and the use of ICT are fundamental indicators (as well as salient issues) of the information society.

However, the term «Global Village» has been slightly distorted in the political discussions, shifting away from the original social communications theory approach to a more economic and structural concept.2 Particularly, key issues of information sciences are at risk to disappear from the scene. This assessment is mainly true for transparency; however, it also applies to accountability and participation. This contribution addresses the links between transparency, accountability and participation as the pillars of the «legitimacy building» in a global society.

- The straight line or straight axle relates to objects (or issues) through a linear (horizontal or vertical) slope.

- The angle constitutes a link between objects (or issues) by using an intermediation point.

- The triangle establishes a link between each of the three objects (or issues); normally, the three links do not encompass the identical legal qualities.

2.1.

Notion and Features of Transparency ^

Exactly hundred years ago, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis phrased the famous sentence: «Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman».3 However, it should not be overlooked that for Brandeis the duty to make information available to the public was a necessary companion to the right to privacy, a concept which he had pioneered.4 Already at that time, transparency implied elements such as shedding light on governments’ actions with regard to data collection, anti-corruption strategies, transactions in financial markets and generally governance issues in legal entities.

At the bottom, transparency is a measure to warrant «market confidence». However, in the real world, the fundamentals of market confidence are neither clear or rational, nor necessarily based on stable evidence and they are not carved in stone.5 Even if the principles for transparency developed in constitutional law are also applicable to ICT features, states should take windows of opportunity to be creative and improve legal certainty by including the inputs of all relevant stakeholders.

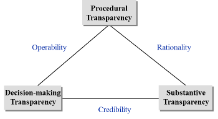

The three pillars can be described in short as follows:6 (i) Procedural transparency encompasses rules and procedures in the operation of organizations, being unambiguously designed and publicly disclosed, and should make the process of governance and lawmaking accessible and comprehensible for the public, including elements such as the due process principle. (ii) Being based on the acknowledgment of access to political mechanisms, decision-making transparency strengthens the institutional credibility and legitimacy of governmental decisions being based on reasoned explanations. (iii) Substantive transparency is directed at the establishment of rules containing the desired substance of regulations, standards and provisions which avoid arbitrary or discriminatory decisions and realize the requirements of rationality and fairness.

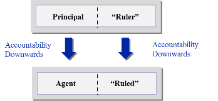

The transparency upwards allows the principal (hierarchical superior) to observe the conduct, behavior, and/or «results» of the agent (hierarchical subordinate). The transparency downwards gives the «ruled» persons the possibility to observe the conduct, behavior, and/or results of their «rulers»; this relationship is well known in democratic theory and can also be seen under the umbrella of the later discussed accountability.7

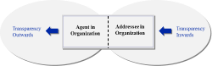

The transparency outwards looks at situations in which the agent is a position to observe what is happening «outside» the organization. The transparency inwards addresses the freedom of information of «outsiders» in having access to elements «inside» the organization.8 This right of access is well known in many fields of law (against governments and their agencies, corporations, data controllers etc.).

2.2.

Transparency in the Internet Address System ^

As mentioned, the principle of transparency must be seen as an important aspect of good regulatory governance, since it allows the exercise of authority to be publicly accessible. The medium of the Internet itself offers valuable opportunities for transparent communications. In order to achieve transparency in the regulatory process, the Internet should be designed in a way that enables the participants to have open access to negotiations, to collect proposals and statements from the various stakeholders concerned, to present the decisions and results, and thereby to enhance and facilitate communication and dialogue between the different Internet governance regulating institutions and the interested parties.9

A thorough review of the existing transparency regulations in the context of ICANN shows that improvements would be possible in various areas, for example in the decision-making processes of the Board and in the restructuring of the three existing review mechanisms for Board recommendations.10 According to the appreciation in the Annual Report 2012 of ICANN the previously submitted recommendations have been fulfilled.11 This assessment does not fully correspond to the reality. Even if the second Accountability and Transparency Review Team (ATRT2) has expressed the opinion that progress was achieved, the experts reached the finding that ICANN «should develop new transparent and accountable mechanisms that combine more effective resource allocation and use with the involvement of all parties within the multi-stakeholder model».12

2.3.

Transparency in Data Protection Matters ^

Transparency contradicts the right of self-determination of data owners to disclose or not to disclose certain data. The concrete rights of data owners are regulated by national data protection laws and international data protection instruments being legally binding or not binding. The extended scope of data collections and of surveillance by different kinds of intelligence bodies puts data protection at risk. Taking the example of big data, analytical models depend of small data inputs, including information around people, places, and things collected by sensors, cellphones, click-patterns, and the like; such small data inputs can aggregate large data sets. Available technics allow acquiring far-reaching insides.13

This assessment gives rise to a so-called transparency paradox. The promise of big data consists in making the world more transparent, however, the collection of data is invisible, its tools and technics are opaque and the different physical, legal and technical layers hardly allow the application of privacy by design rules. Therefore, question can be asked why the big data (r)evolution is mostly occurring in secret.14

Obviously, business secrecy provisions allow opposing to transparency requests made by the concerned data owners. The data collection can also be connected to highly sensitive intellectual property rights and national security assets. But, as correctly observed, if «big data analytics are increasingly being used to make decisions about individual people, those people have a right to know on what basis those decisions are made».15

A certain remedy could be seen in the call for a «technological due process» that should apply to both governmental and corporate decisions.16 In view of the data protection threats caused by cloud computing, big data and surveillance measures, technical, commercial, ethical and legal safeguards are to be developed in order to safeguard accepted non-disclosure requests of individuals. In a democratic society, a system, or even the appearance of a system, allowing secret surveillance or opaque and unreviewable (i.e. Kafkaesque) decision-making is not acceptable.17 In particular, procedural transparency merits a better implementation, thereby contributing to transparency downwards.

3.1.

Notion and Features of Accountability ^

Accountability, stemming from the Latin word accomptare, is the acknowledgement and assumption of responsibility for actions, products, decisions, and policies within the scope of the designated role. Various types of accountability can be distinguished, namely moral, administrative, political, immaterial, market, legal/traditional, constituency related and professional accountability.18 Transparency through the making available of reliable information being accessible both logistically and intellectually is a condition for accountability.

3.2.

Accountability in the Internet Address System ^

The first thorough review of the accountability mechanisms within ICANN came to the conclusion that «despite the importance accorded to configurations of accountability for ICANN, there is neither a standard working definition of accountability nor agreements on metrics to monitor and measure progress».19 The ATRT1 issued 27 recommendations looking at manifold angles of accountability. The ICANN Annual Report 2012 negates the existence of an accountability gap by claiming that all 27 recommendations were already implemented.20

The assessment of ATRT2 regarding the implementation of the recommendations is relatively vague so far. Nevertheless, the ATRT2 is of the opinion that ICANN should reconsider the Ombudsman’s charter as a symbol of good governance to be further incorporated into accountability processes.21 In fact, the implementation of stricter requirements seems to be adequate. In democratic nation states, accountability is typically bolstered through institutional checks and balances which do not yet exist within ICANN. The implementation of consultation processes could help streamline the realization of envisaged policies. Civil society should not only be consulted in the preparatory phase of any project, but also be informed after its implementation. Feedback mechanisms concerning review processes need to be consistently utilized being an aspect which should allow the participants in the process to understand how their insights and expertise have influenced the policy outcomes.22 Furthermore, accountability must be able to enclose some sort of disciplinary and enforcement powers, thus attaching costs to the failure to meet the standards.23

In addition, the presently weak review procedures giving the Board of ICANN almost unchecked autonomy must be changed; the ICANN Board should not continue acting as the ultimate arbiter of its own disputes.24 Reconsideration might be worthwhile under certain circumstances, but it is not sufficient to cover all complaints’ issues. The improvement of the Ombudsman system can support the search for amicable settlements. Nevertheless, a Board of Review should be established, composed of legally educated members being independent from ICANN and its officers. Decisions should be issued in the form of written opinions explaining in what respect the disputed action did or did not comply with the corporate documentation of ICANN.25 Consequently, from a theoretical perspective, major attention must be paid to the accountability downwards (compliance review, sanctions’ application) that would have a positive influence on the credibility of the given framework.

3.3.

Accountability in Data Protection Matters ^

Looking from a public interest angle, big data analyses must be executed under an accountability umbrella. Standards need to be implemented that induce the collector of data to handle the data in a responsible way.26 The substantive foundation for concretizing this responsibility can be found in the data protection principles, namely the proportionality, the objective orientation, and the good faith principle. Such kind of accountability regime is the corresponding obligation to the vast opportunities given by big data analyses.27 As in the case of the Internet address system, the main issue concerns the accountability downwards; if accountability is realized, the credibility of big data activities might increase.

4.1.

Notion and Features of Participation ^

Contrary to transparency and accountability, participation is rather to be seen as an angle than as a triangle since consultation and active determination in decision-making processes are two different kinds of participation. Consultation does not necessarily build a link to the active inclusion and vice versa. During the last few years, the term «multistakeholderism» has been coined for describing the consultation and inclusion elements with regard to all stakeholders in the governance processes and the joint involvement of all stakeholders who have the necessary know-how being desirable to strengthen the public’s confidence in decision-making processes.28

4.2.

Participation in the Internet Address System ^

No. 4 of the Affirmation of Commitments29 refers to the existence of a multistakeholder development model acting for the benefit of global Internet users by highlighting the importance of ICANN to maintain and improve robust mechanisms and to make its decisions not just in the interest of a particular set of stakeholders but in the public interest. ICANN is aware of the respective needs and the Annual Report 2012 emphasizes the necessity to have a «bottom-up, consensus-driven, multistakeholder model».30 The Annual Report 2012 also refers to the continuously increasing number of attendees at the meetings adding their voices to the discussion (including remote participation).31 Nevertheless, more stakeholder groups could still be motivated to participate in widened consultation opportunities.

A specific approach adopted from national democratic frameworks could consist in the implementation of direct elections. The original attempt of ICANN to integrate direct elections of (a part of) its Board into its organizational structure was deemed a failure in the year 2000 and consequently stopped in view of the very small percentage of voting Internet users who actually participated in the elections. However, the question whether the termination of that experiment was in fact the right decision remains doubtful, especially because the other option of encouraging the public to vote was not even given a chance; the untried option would admittedly have contributed to an improvement of participation.32 Insofar, active inclusion of stakeholders still remains an important objective in order to improve their influence.

4.3.

Participation in Data Protection Matters ^

As mentioned, big data analyses bring benefits and risks. In order to adequately balance potential gains and losses big data analysts and concerned individuals could agree on a «sharing the wealth» strategy. Data controllers should provide individuals with access to their data in a usable format, allowing them to take advantage of the applications and draw useful (personal) conclusions; consequently, organizations must be induced to share with the individuals the wealth their data helps create.33

Access creates value to individuals since they have the ability to use and benefit from their own personal data in a tangible way.34 The «sharing the wealth» strategy could lead to an ecosystem that allows to appropriately allocate rights and obligations. Therefore, individuals should have a right of exit from the market and opt-in default rules could reduce information asymmetry and support disclosure.35 In addition, enterprises should not only be liable for damages in case of abuses, but also be incentivized to comply with bargained-for terms and legal safeguards (oversight function).36 In this big data field, consultation and active inclusion are underdeveloped and need to be tackled by the concerned entities.

5.

Concluding Assessment of the Links between Transparency, Accountability and Participation ^

Rolf H. Weber

Chair Professor University of Zurich, Faculty of Law

Ramistrasse 74/38, 8001 Zurich, CH

rolf.weber@rwi.uzh.ch; http://www.rwi.uzh.ch/weberr

- 1 Weber, R. H., Shaping Internet Governance: Regulatory Challenges, Zurich (2009), p. 9.

- 2 Weber, n 1, pp. 9/10.

- 3 Brandeis, L., Other People’s Money: And How the Bankers Use it, New York (1914), p. 92.

- 4 Warren, S. D./Brandeis, L., The Right to Privacy, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 4 (1890), p. 193.

- 5 Kaufmann, Ch./Weber, R. H., The Role of Transparency in Financial Regulation, Journal of International Economic Law, Vol. 13(3) (2010), p. 779.

- 6 Weber, n 1, p. 122.

- 7 See para 3 hereinafter.

- 8 Weber, n 1, p. 122.

- 9 For the transparency commitments of ICANN see Art. III Sec. 1 of its Bylaws and No. 7 of its Core Values.

- 10 Accountability and Transparency Review Team 1, Final Recommendations of the Accountability and Transparency Review Team, December 31, 2010, http://www.icann.org/en/about/aoc-review/atrt/final-recommendations-31dec10-en.pdf.

- 11 ICANN, Annual Report 2012, http://www.icann.org/en/about/annual-report/annual-report-2012-en.pdf.

- 12 Accountability and Transparency Review Team 2, Report of Draft Recommendations for Public Comment, 15 October 2013, http://www.icann.org/en/about/aoc-review/atrt/draft-recommendations-15oct13-en.pdf.

- 13 Weber, R. H., Big Data: Sprengkörper des Datenschutzrechts, in: Jusletter 11 December 2013, margin number 13, http://jusletter-eu.weblaw.ch/magnoliaPublic/issues/2013/11-Dezember-2013/2274.html.

- 14 Richards, N. M./King, J. H., Three Paradoxes of Big Data, Stanford Law Review Online, Vol. 66, 3 September 2013, p. 42.

- 15 Richards/King, n 14, p. 43.

- 16 Citron, D. K., Technological Due Process, Washington University Law Review, Vol. 85 (2008), p. 1249 ff.

- 17 Richards/ King, n 14, p. 43.

- 18 Weber, n 1, p. 133.

- 19 Accountability and Transparency Review Team 1, n 10.

- 20 ICANN, Annual Report 2012, n 11, p. 16.

- 21 Accountability and Transparency Review Team 2, n 12, p. 48.

- 22 Weber, R. H., The legitimacy and accountability of the internet’s governing institutions, in: Brown (ed), Research Handbook on Governance of the Internet, Northampton (2013), pp. 99-119, p. 114.

- 23 Weber, n 22, p. 117.

- 24 Weber, R. H./Gunnarson, R. S., A Constitutional Solution for Internet Governance, Columbia Science and Technology Law Review, Vol. 14 (2012), p. 69.

- 25 Weber/Gunnarson, n 24, p. 71.

- 26 Weber, n 13, margin number 57.

- 27 See also Mayer-Schönberger, V./Cukier, K., Big Data, A Revolution, New York (2013), p. 175.

- 28 Weber, R. H., Visions of Political Power: Treaty Making and Multistakeholder Understanding, in: Radu/Chenou/Weber (eds), The Evolution of Global Internet Governance, Zurich (2013), p. 96.

- 29 Affirmation of Commitments by the United States Department of Commerce and the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, http://www.icann.org/en/about/agreements/aoc/affirmation-of-commitments-30sep09-en.htm.

- 30 ICANN Annual Report 2012, n 11, p. 2.

- 31 ICANN Annual Report 2012, n 11, p. 13.

- 32 Weber, n 22, p. 115.-*

- 33 Rubinstein, I. S., Big Data: The End of Privacy or a New Beginning?, International Data Privacy Law, Vol. 3(2) (2013), p. 8.

- 34 Rubinstein, n 33, p. 8.

- 35 See also Schwartz, P. M., Property, Privacy, and Personal Data, Harvard Law Review, Vol. 117 (2004), p. 2100.

- 36 Rubinstein, n 33, p. 8.