1.

Introduktion ^

According to mainstream socio-economic theories, HR treaties are empty promises,1 as they finally apply to the citizen-government relationship,2 where other states do not want to interfere,3 where the threat of retaliation by compliant states against deviants becomes meaningless, and where there are neither strong multinational enforcing mechanisms nor market forces that ensure compliance. This conclusion was also supported by statistical analysis of HR treaties, in particular time series analysis comparing HR fulfilment prior to and after treaty ratifications.4 Rich democratic countries without internal conflicts rather appear to comply, strong civil society organizations enhance respect for HR treaties,5 and also countries accepting enforcement mechanisms (optional protocols) in general have a better HR record.6 However, in autocratic societies the ratification of treaties may have negative impact on HR and, for instance, rewarding developing countries with more aid for accession to HR treaties has shown to be counterproductive.7 This suggestion that HR treaties may be futile stirred an academic debate that is still ongoing. Opponents proposed the thesis that on the contrary a process of acculturation may ensure growing respect of HR,8 considering that the legitimacy of governments increasingly hinges on their democratic conduct.9

2.

Empirical Materials and Methods ^

This paper is based on the empirical information of a complementary paper (FN 12), where authors studied the HR situation of persons in SW. Thereby, for this paper SW means sexual behaviour of consenting adults involving physical contacts in exchange for monetary gains. Women in SW are vulnerable to HR violations,13 whereby the reasons are similar across countries:14 There are issues of stigma and social injustice.15 For the assessment the authors defined an index SWDEF, at which SWDEF of a country is 1, if there are verified reports, published between 2007 and 2012, about deficiencies affecting SWs, and it is 0 otherwise (see Table 2). Some feminists consider SW per se as HR violation of the «prostituted women».16 This hypothesis is not accepted, as it would blur differences and as the focus of SWDEF is on serious violations, such as police brutality, and on discriminations against SWs by the law and by legal practices. For instance, coercive measures against SWs, such as compulsory or forced HIV tests, are counterproductive and discriminate against women.17 Where such measures are applied (e.g. Austria), SWDEF = 1. Authors linked SWDEF to population size,18 to the legal approaches towards SW (prohibitionist, abolitionist, neo-abolitionist, or regulationist),19 to their implementation (liberal or conservative),20 and in the complementary paper also to reported levels of HR fulfilment according to the Cingranelli & Richards HR database,21 and to proven HR violations in terms of violation propensity (VP),22 an annual average of ECtHR judgments finding violations per million citizens.

3.

Discussion of CoE Treaties ^

3.1.

Treaties in Group 1 ^

The CoE Treaties selected for the first group deal with the protection of HR of the «first generation».25 These are civil and political rights and have a (rather) high relevance for the topic of SW. The derived societal preferences of interest are linked with particular approaches of HR protection. The discussion of ECtHR judgments is cited from an ECtHR analysis.26 Group 1 comprises the following conventions:

- a. Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS 197) has been considered by ECtHR in key judgments.

CETS 197 is directly related to SWDEF and reflects a societal preference for recognizing a state’s duty to actively protect HR positions and particularly violations of human dignity (explicitly Article 6 lit d and Article 16), even the threats caused by other private persons from abroad. Remarkably the treaty requires «preventive measures, including educational programmes for boys and girls during their schooling, which stress the unacceptable nature of discrimination based on sex, and its disastrous consequences, the importance of gender equality and the dignity and integrity of every human being.» The convention emphasizes the «HR-based approach» as well as the gender mainstreaming-principle (Article 5 § 3). Furthermore, the – here relevant – group of (mainly female) SW is recognized as particularly vulnerable, expressed by the Preambles» reference to Recommendation 1325 (1997) of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe on Traffic in Women and Forced Prostitution in Council of Europe Member States and to Recommendation 1610 (2003) on Migration Connected with Trafficking in Women and Prostitution. Altogether the instrument shows a very modern approach of HR protection beyond the mere level of respecting them by state actors.

- b. Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data (CETS 108) has been considered by ECtHR in landmark judgments on data protection.

This convention reflects a preference for enhanced privacy protection in respect of processing personal data by modern technical means. Thus, a ratification of this convention shows the willingness of a state to take active (legislative) measures not just for the vertical relation between state and citizens but also for the horizontal relation of citizens among each other. This shows an approach beyond the core of privacy protection as granted e.g. by Article 8 of ECHR recognizing the «informational self-determination» as a crucial issue in a democratic society.27 Furthermore, with respect to the field of SW, CETS 108 recognizes the particular sensitivity of data (information) regarding a person’s sexual life by requiring a special level of protection for such data (see Article 6). Last but not least the convention sets out a special cooperative approach among the signing states particularly as they have to provide assistance to their citizens abroad in case of violations of the conventions rights.

- c. Additional Protocol to the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with Regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data, Regarding Supervisory Authorities and Transborder Data Flows (CETS 181) had no independent importance in the case law of ECtHR.

Basically the assessment to CETS 108 also applies to CETS 181. However, this protocol contains a crucial added value with the obligation to «provide for one or more authorities to be responsible for ensuring compliance with the measures in its domestic law giving effect to the principles stated in Chapters II and III of the Convention and in this Protocol» (Article 1 § 1). The supervisory authority shall be established with all powers for «giving effect to the principles mentioned in paragraph 1 of Article 1 of this Protocol» (Article 1 § 2), it shall be independent (§ 3) and remedies against the supervisory authority’s decisions shall be provided. Thus, the additional protocol shows a preference for not just only respecting the right to data protection but to fulfil it by providing an environment in which the rights can be actually realized.28 Regarding the relevance for SWEDF; international information exchange is an important issue for trafficking of human beings, which frequently goes together with forced prostitution.

The convention reflects a preference for positive measures to combat threats of very modern kind by the means of youngest technological developments. Moreover, the Preamble stipulates the «need to ensure a proper balance between the interests of law enforcement and respect for fundamental HR» as enshrined in the ECHR, particularly mentioning the freedom of expression and information as well as the right to privacy. Remarkable is the requirement for states «to ensure that legal persons can be held liable for a criminal offence established in accordance with this Convention» (Article 12 –Corporate liability), which is a very modern approach reflecting a preference for accountability of legal persons under criminal law.

- e. European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages (CETS 148) establishes protection of minorities as a legitimate aim, as pointed out by the former European Commission on HR.

Its ratification shows the willingness of a country to domestically recognize the importance of protecting vulnerable groups. It shows a societal preference that has also (indirect) relevance for the topic of SW, as multiple vulnerabilities may boost each other.30 In the end, this affects also SWs» enjoyment of HR of the first generation.

- f. Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (CETS 157) is frequently and in different contexts cited by the ECtHR, as it demonstrates consensus about the need to protect the security, identity and the lifestyle of minorities.

3.2.

Treaties in Group 2 ^

The CoE treaties selected for group 2 regard either HR of the second generation or deal with topics beyond classical HR protection. Some of them are not even relevant for the topic of SW. They are nevertheless of interest, as they reflect societal preferences not covered in the first group. Thus, group 2 comprises the following six conventions:

- a. European Social Charter (CETS 035) is amongst CoE conventions that ECtHR cited most often, as it provides evidence for consensus about fair working conditions, including e.g. the right to form trade unions.

The Charter as «counterpart» to the ECHR provides HR of the second generation and comprises topics such as housing, health, education, employment, legal and social protection, migration as well as non-discrimination.32 Its ratification reflects clearly a societal preference for achieving social justice by granting litigable rights. In a historical view this approach even appeared as a fundamental cleavage between eastern and western countries during the cold war. It is indirectly but highly relevant for the topic of SW since a strong link between denial of SWs» rights and social injustice has been recognized.33

- b. European Code of Social Security (CETS 048) has been considered by ECtHR in the context of the protection of social security benefits as property rights.

Regarding the relevance for SW and the reflected societal preferences it shall be referred to the European Social Charter with similar arguments, but with a narrower scope.

- c. European Convention on the Obtaining Abroad of Information and Evidence in Administrative Matters (CETS 100) had no independent importance in the case law of ECtHR, as it concerns mainly inter-governmental cooperation.

The ratification of this convention may indicate the willingness of a country for transparent information sharing and international cooperation at all levels, similarly to CETS 181 above.

- d. European Convention on the Control of the Acquisition and Possession of Firearms by Individuals (CETS 101) had no independent importance in the case law of ECtHR.

The relevance for the topic of SW is just indirect and on the very periphery. Non-ratification might indicate a preference against precautionary measures (here: crime prevention by arms restrictions), affecting also other administrative and legal approaches.

- e. European Agreement on the Restriction of the Use of certain Detergents in Washing and Cleaning Products (CETS 064) had no independent importance in the case law of ECtHR.

The convention is not relevant for the topic of SW. However, it is selected due to the reflected societal preference: Ratification informs about the willingness to extend the scope of classical HR protection with a focus on cultural and social issues.

- f. European Convention for the Protection of Pet Animals (CETS 125) had no independent importance in the case law of ECtHR.

4.

Country Classification ^

4.1.

Problem: Explanation of Ratification Types ^

- Eight countries (152 million citizens) are of type A; they did not ratify all three of the conventions 1b (CETS 108), 1c (CETS 181), 1d (CETS 185) and they did not ratify 2d (CETS 101), 2e (CETS 125), or 2f (CETS 064).

- Five countries (160 million citizens) are of type B; they ratified 2a (CETS 035), 2d (CETS 101), 2e (CETS 125) and at least one of 2c (CETS 100) or 2f (CETS 064).

- Fifteen countries (115 million citizens) are of type C; they ratified all three conventions 1b (CETS 108), 1c (CETS 181), 1d (CETS 185) plus 1f (CETS 157), but did not ratify 2b (CETS 048), 2c (CETS 100), 2d (CETS 101), or 2f (CETS 064).

- Four countries (33 million citizens) are of type D; they ratified 2b (CETS 048), but not 2a (CETS 035).

- All other 15 countries (360 million citizens) are of type E (other combinations).

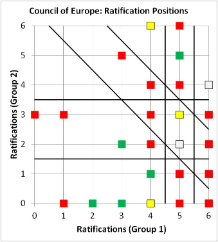

Figure 1. SWDEF in relation to the number of ratifications

Explanation: Graphic with MS Office.

Colours code positions; red: SWDEF = 1 for all countries at that position (15 positions, 27 countries); green: SWDEF = 0 for all countries at that position (5 positions, 8 countries), yellow: SWDEF = 1, if implementation of prostitution laws is conservative, and SWDEF = 0 for the other countries in that position (3 positions, 7 countries); grey: SWDEF = 0, if countries are liberal and not abolitionist, and SWDEF = 1 for the other countries in that position (2 positions, 5 countries).

Boldface lines separate activity levels: Countries are passive in a group or in the set of all twelve ratifications, if they are amongst the 50% countries with least ratifications (up to four ratifications in group 1, no or one ratification in group 2, or up to six ratifications overall). They are active, if they are in the upper third of countries in ratifications (six or more ratifications in group 1, four or more in group 2, or nine or more overall). Countries are intermediate, if the number of ratifications is in between.

- With the exception of Ireland, type A countries are passive in both groups. With the exception of Estonia (type D), this «reluctance» correctly identifies type A membership.

- Countries of type B are active in overall ratifications, but not active in group 1. With the exception of Sweden (type E), this correctly identifies type B countries.

Figure 2. Comparing countries by their similar positions towards treaties

Explanation: nodes = countries; links = ratification status equal for at least 10 conventions; overlapping nodes: equal ratification status for all 12 conventions; node size by degree (number of links to other nodes); colour code: blue = type A, green = type B, red = type C, yellow = type D; grey = type E; shape code: circle = SWDEF = 0, squares = SWDEF = 1 (graphic: -UCINET 6 software, using computations with XL-Stat software).

4.2.

Alternative Route to Classifications ^

5.

Conclusions ^

6.

Annex: Data ^

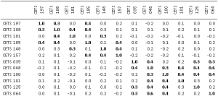

Table 1. Correlation coefficients for treaty ratification

Explanation: Pearson correlation coefficients between ratifications of the treaties listed in Table 2. T-test was used to identify the 95% significant coefficients; they are in boldface.

Norbert Brunner

Centre for Environmental Management and Decision Support (C-EMDS) and Mathematics, DIBB, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU)

Gregor Mendel Strasse 33, 1180 Wien, AT

Christof Tschohl

Wissenschaftlicher Leiter, Research Institute AG & Co KG – Zentrum für digitale Menschenrechte

Amundsenstraße 9, 1170 Wien, AT

christof.tschohl@researchinstitute.at; http://researchinstitute.at

- 1 Hafner-Burton, E.M., Tsutsui, K. (2005). Human Rights in a Globalizing World: The Paradox of Empty Promises. American Journal of Sociology, 111, 1373–1411.

- 2 Typically international treaties require a domestic ratification law for granting rights directly to citizens towards their state, whereas a complaint mechanism on international level, such as for ECHR, is rather exceptional; Wagnerova, E. (2005). The direct applicability of human rights treaties, CoE Report CDL-UD(2005)012rep, 3 ff.

- 3 Explaining the mechanism and citing the low number of inter-state-cases according to Article 33 ECHR.

- 4 Hathaway, O.A. (2002). Do Human Rights Treaties Make a Difference? Yale Law Journal, 111, 1935–2042.

- 5 Neumayer, E. (2005). Do International Human Rights Treaties Improve Respect for Human Rights? Journal of Conflict Resolution, 49, 925–953.

- 6 Cole, W.M. (2009). Hard and Soft Commitments to Human Rights Treaties, 1966–2000. Sociological Forum, 24, 563–588.

- 7 Magesan, A. (2013). Human Rights Treaty Ratification of Aid Receiving Countries. World Development, 45, 175–188.

- 8 Goodman, R., Jinks, D. (2008). Incomplete Internalization and Compliance with Human Rights Law. European Journal of International Law, 19, 725–748.

- 9 D’Aspremont, J. (2006). Legitimacy of Governments in the Age of Democracy. New York University Journal of International Law and Politics, 38, 877–897.

- 10 Chayes, A., Chayes, A. (1995). The New Sovereignty: Compliance with International Regulatory Agreements. Harvard UP, Cambridge.

- 11 Hawkins, D., Jacoby, W. (2008). Agent Permeability, Principal Delegation and the European Court of Human Rights. Review of International Organizations, 3, 1–28.

- 12 Brunner, N., Tschohl, C. (2013). Assessment and Explanation of the Human Rights Situation of a Ubiquitous Minority in Europe. To be published in Jusletter-IT (Weblaw), March 2013. In addition, supporting information for that paper is available online; it collects the empirical data used.

- 13 UNAIDS (2012). Guidance Note on HIV and Sex Work. Joint UN Program on HIV/AIDS, joint publication with OHCHR, Geneva (original publication 2009, update 2012).

- 14 Harcourt, C., Donovan, B. (2005). The Many Faces of Sex Work. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 81, 201–206.

- 15 Nussbaum, M. (1998). Sex and Social Justice, Oxford UP, Oxford.

- 16 Farley, M. (2004). Bad for the Body, Bad for the Heart: Prostitution Harms Women even if Legalized or Decriminalized. Violence Against Women, 10, 1087–1125.

- 17 CEDAW (2003). Background Paper Concerning Article 6 of the Convention. CEDAW/2003/II/WP.2 of 13 March 2003, UN OHCHR, Geneva.

- 18 UNO (2011). World Population Prospects. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, New York.

- 19 PACE (2007). Prostitution – Which Stance to Take? Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Recommendation 1815, Document 11352 of 9 July 2007.

- 20 Implementation of prostitution laws (even, if there are none) is conservative, if law enforcement actually restricts SW, and liberal otherwise; SWFV (2012). Human Rights of Sex Workers in Europe. A Survey and Critical Analysis. Sex-Worker Forum of Vienna, www.sexworker.at.

- 21 Cingranelli, D.L., Richards, D.L. (2013). The Human Rights Dataset, www.humanrightsdata.org.

- 22 VP is based on data inECtHR (2012). Violations by Article and by State, 1959 to 2011. Registry, ECtHR, Strasbourg.

- 23 Table 1: Each treaty defines a vector of 47 entries (0 = not ratified, 1 = ratified), each for one CoE member state, which is used to compute correlation coefficients.

- 24 Reinprecht, C. (2012), Human Rights from a Sociological Perspective, in: Nowak, M., Januszewski, K., Hofstätter, T. (Ed.), All Human Rights for All. Vienna Manual on Human Rights, Vienna – Graz 2012, 51.

- 25 Human rights theory distinguishes three «generations» of human rights: 1. civil and political rights; 2. economic, social and cultural rights; 3. peoples right to self-determination and development; see Nowak, M. (2012), Human Rights Theory, in: Nowak, M., Januszewski, K., Hofstätter, T. (Ed.), All Human Rights for All. Vienna Manual on Human Rights, Vienna – Graz 2012, 269.

- 26 ECtHR (2011). The Use of Council of Europe Treaties in the Case-Law of the European Court of Human Rights. Research Division, ECtHR, Strasbourg.

- 27 The Constitutional Court of Germany developed the «right to informational self-determination» in its famous jurisprudence to a domestic census derived from Article 1 (human dignity) and Article 2 (free personal development) German Constitution, BVerfG, 15 December 1983 – 1 BvR 209/83 et al. (Volkszählungsurteil).

- 28 For the dimensions «respect – protect – fulfil» in human rights theory see Nowak, M. (2012), Human Rights Theory, in: Nowak, M., Januszewski, K., Hofstätter, T. (Ed.), All Human Rights for All. Vienna Manual on Human Rights, Vienna – Graz 2012, 270 f.

- 29 ECtHR 2 March 2009, K.U. v. Finland, No. 2872/02, citing Article 15, 18, 21 and 22 as relevant international law and used by the court to exemplify cybercrime as an offense to guarantees contained in Articles 8 and 10 of ECHR.

- 30 For instance, in Serbia SWs were specifically targeted by police for acts of brutality, if they were of Roma origin or transgender;Rhodes, T., Simić, M., Baroš, S., Platt, L., Žikić, B. (2008). Police Violence and Sexual Risk among Female and Transvestite Sex Workers in Serbia: Qualitative Study. British Medical Journal, 337, a811.

- 31 For the concept of this dimensions see above Fn. 28.

- 32 Lukas, K. (2012), The European Social Charter in the European Monitoring System, in: Nowak, M., Januszewski, K., Hofstätter, T. (Ed.), All Human Rights for All. Vienna Manual on Human Rights, Vienna – Graz 2012, 135.

- 33 Nussbaum, M. (1998). Sex and Social Justice, Oxford UP, Oxford.

- 34 Goodliffe J., Hawkins D. (2009). A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to Rome: Explaining International Criminal Court Negotiations. Journal of Policy, 71, 977–997.

- 35 Jolliffe, I.T. (2002). Principal Component Analysis. Springer Series in Statistics, Heidelberg.

- 36 Roche, J.M. (2008). Monitoring Inequality among Social Groups: A Methodology Combining Fuzzy Set Theory and Principal Component Analysis. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 9, 427–452.

- 37 For details see the complementary paper (Fn. 12).

- 38 See the introduction for such literature and the complementary paper (FN 12) for more on patterns.

- 39 Avdan, N. (2012). Human Trafficking and Migration Control Policy: Vicious or Virtuous Cycle? Journal of Public Policy, 32, 171–205; Castañeda, H. (2009). Illegality as Risk Factor: A Survey of Unauthorized Migrant Patients in a Berlin Clinic. Social Science & Medicine, 68, 1552–1560.

- 40 Busza, J. (2004). Sex Work and Migration. The Dangers of Oversimplification – A Case Study of Vietnamese Women in Cambodia. Health & Human Rights, 7, 231–249; Stark, O., Fan, S. (2011). Migration for Degrading Work as an Escape from Humiliation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 77, 241–247.

- 41 Cho, S.Y., Dreher, A., Neumayer, E. (2012). Does Legalized Prostitution Increase Human Trafficking? World Development, 41, 67–82; Weitzer, R. (2007). The Social Construction of Sex Trafficking: Ideology and Institutionalization of a Moral Crusade. Politics & Society, 35, 447–475.

- 42 Gertler, P., Shah, M. (2011). Sex Work and Infection: What’s Law Enforcement Got to Do with It? Journal of Law & Economics, 54, 811–840.

- 43 Elliot, R., Utyasheva, L., Zack, E. (2009). HIV, Disability and Discrimination: Making the Links in International and Domestic Human Rights Law. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 12, 1/29.